The 30 Greatest Human Villains In Movie History

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

As Alfred Hitchcock once said, it's often the villain that makes or breaks a film. A good baddie, one who is well-developed and/or a plausible foil for the hero, is often the most interesting character in the movie.

It's all too easy to come up with a monstrous appearance for a film's antagonist, and the advances in CGI and special effects have led to an abundance of fantastically designed supervillains and malevolent supernatural entities. More often, though, it's the human villains who reveal themselves to be the most intriguing. They usually contain characteristics we try to repress within ourselves, such as ambition, greed, ruthlessness, and the freedom to act without the constraint of morality, all with the vulnerability that comes from being mortal.

Setting aside our favorite science fiction or supernatural villains (with apologies to Freddy and Jason), below are 20 of the most memorable human villains, some nuanced, others evil personified, but all iconic characters.

Bridget Gregory in The Last Seduction

John Dahl's "The Last Seduction" is one of the most fatalistic and underrated neo-noirs of the '90s. Linda Fiorentino is incredible as the unapologetically coldhearted Bridget Gregory, who makes other femme fatales look tame by comparison. The only character who seems to get on with her is J.T. Walsh's cutthroat lawyer who admiringly calls her a "self-serving b***h."

Traditionally, the femme fatale's true nature is only revealed at the end of the film (See: "The Killers," "The Maltese Falcon," and Dahl's own "Red Rock West"), but as the film's screenwriter Steve Barancik told BBC, it's "more interesting being privy to her machinations than blind to them." As such, Bridget barely tries to hide her true nature. A lesser film might have given her a tragic backstory or a heart of gold, but that's not the case here. As she says herself, "I am a total f***ing b***h," and she is openly contemptuous of Peter Berg's guileless character from the moment she meets him, right up until the point where she coldly sets him up in the movie's closing moments.

Bridget's not a bunny boiler like Glenn Close in "Fatal Attraction," or a sociopath like Rosamund Pike in "Gone Girl." Instead, she's much scarier — a ruthless, calculating character who uses men as a means to an end. The character is so successful in her scheming that by the film's conclusion we are almost in awe of her. (Nick Bartlett)

Alonzo Harris in Training Day

Denzel Washington's Oscar-winning portrayal of Alonzo Harris in "Training Day" still holds up today largely due to his incredibly charismatic performance. The casting is crucial as Washington has made a career out of playing morally upstanding characters, so you want him to be heroic here, too. What makes Harris such a great villain is the way he convinces both the audience and his new recruit Jake Hoyt (Ethan Hawke) that he's merely an unconventional, rough around the edges detective — think Popeye Doyle or Dirty Harry — when he's really up to his neck in corruption. In turn, Hoyt's "induction" ultimately serves as a way for Harris to gauge exactly how malleable and corruptible he is.

Harris' motivations are left ambiguous for most of the film, and he constantly wrong-foots both Hoyt and the audience. Director Antoine Fuqua raises many red flags over the course of the film, but Washington almost convinces us that he's a good guy through the sheer force of his personality. His dynamic performance never betrays his true character either way — he switches between charming to sinister mid-blink. It's only towards the end of the film that we see he has been manipulating Hoyt all along, entrapping him so he has no choice but to follow Harris' orders, and then setting Hoyt up to be killed when he refuses to go along with his actions. (Nick Bartlett)

John Doe in Se7en

The idea of "the banality of evil" is perfectly embodied by Kevin Spacey in David Fincher's "Se7en," playing a seemingly normal man who commits some of the most horrific murders ever committed to film.

John Doe appears 90 minutes into the film's runtime, and we never actually see him kill any of his victims, only the grisly aftermath. In the absence of a physical presence, you could be forgiven for thinking the killer is somehow more than human, or at the very least a raving psychopath. But as Detective Somerset (Morgan Freeman) puts it: "If we catch John Doe and he turns out to be the devil, I mean Satan himself, that might live up to our expectations, but he's not the devil. He's just a man."

And so he is. As played by Spacey, John Doe is just a mild-mannered, incredibly creepy man. There's a meditative stillness to Spacey's performance that's almost unnatural; he remains unflappable right until the ending. The only moment he loses his composure is when Detective Mills (Brad Pitt) calls his victims "innocent" — a claim that sends Doe off on a self-righteous rant justifying his killings. (Nick Bartlett)

Tigrero in The Great Silence

There are plenty of memorable villains in the Spaghetti western genre, such as Henry Fonda in "Once Upon A Time In The West" or Lee Van Cleef in "The Good The Bad And The Ugly," but none of them are quite so repellent as Klaus Kinski in "The Great Silence." Tigrero (or Loco, depending on which version of the film you watch) is different in that he operates entirely within the boundaries of the law. In another film, he might be the hero — a bounty hunter who brings in dangerous outlaws living in the hills. However, the warrants on these fugitives have been drawn up by the town's corrupt mayor, and Tigrero never brings them in alive.

He also seems to derive great pleasure in outwitting his quarry, justifying the killings with legal red tape. Kinski played his share of villains, in "Aguirre, The Wrath Of God" and "Nosferatu The Vampyre," for example, but he seems to genuinely relish his role here. In arguably the most gleefully malevolent performance of his career, he makes Tigrero a character you love to hate; a truly odious villain decked out in a luxurious fur coat. This all contributes to what is potentially the most downbeat ending of any western movie. (Nick Bartlett)

Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity

It might be Fred MacMurray's seedy life insurance salesman Walter Neff who commits the pivotal murder in Billy Wilder's seminal film noir "Double Indemnity," but it's Barbara Stanwyck's sultry Phyllis Dietrichson who emerges as the infinitely more ruthless character. Wilder's first choice for the role, Stanwyck was best known at that point for her light comedy performances in "The Lady Eve" and "Meet John Doe." She was hesitant to take on such a villainous role, but her performance in "Double Indemnity" proved to be one of the most definitive femme fatales, setting the tone for the many that would follow, from Ava Gardner to Rita Hayworth.

Her introductory scene is iconic in itself, as we see her standing on her balcony wrapped in a towel. It's a calculated move to seduce Walter, and she quickly plants the idea of murdering her husband, only to become increasingly bloodthirsty as the film goes on. Most of her villainy occurs off-screen, relayed to Neff by her stepdaughter, as we hear about her sinister past. We don't need exposition, though, when her nature is evident in the murder scene. In what was ostensibly a way to maneuver past the production code, Wilder keeps the camera on Phyllis as Neff murders her husband in the next seat. The carnal look that crosses her face as we hear her husband's struggles is chilling, and an iconic moment in the genre. (Nick Bartlett)

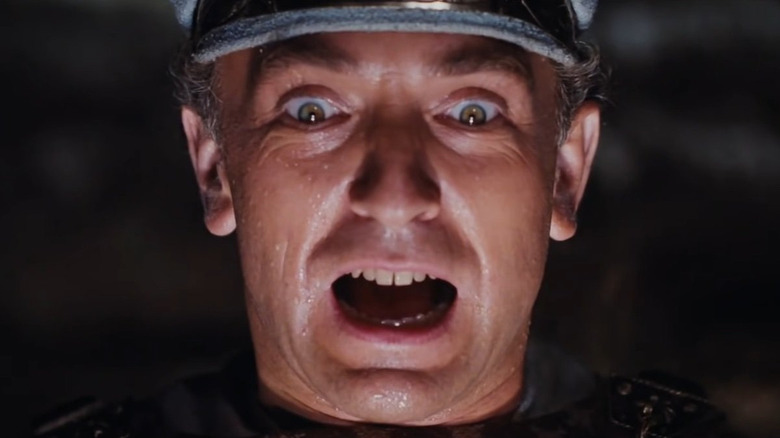

Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds

Of all the iconic villains Quentin Tarantino has created (including Mr. Blonde, Stuntman Mike, Elle Driver), the filmmaker has called Hans Landa "the best character I've ever written and maybe the best I ever will write," and it's easy to see why. Christoph Waltz's Oscar-winning performance as "The Jew Hunter" in "Inglourious Basterds" is captivating from the very first scene, where he effortlessly slips between languages and from friendly chit-chat to sinister interrogation without missing a beat. His delivery makes Tarantino's often mannered dialogue positively sing.

Landa is a character who is almost always in control. It's clear he takes pride in theatricality, and the opening scene is choreographed to the letter. He describes himself as a detective rather than a Nazi, and indeed, what differentiates Landa from the numerous other Nazi film villains is that he isn't a fanatic. He is shown to not have many convictions at all, which should make him more sympathetic, but if anything he becomes more horrifying. His antisemitism is a lot more subversive and insidious than the hatred that is usually depicted onscreen.

He seems completely unprincipled until the terrifying moment where he drops his facade and strangles Diane Kruger's Bridget to death in a burst of rage, but even this seems to be motivated by personal hatred than anything else. Landa is a fascinating creation, a disarmingly polite pragmatist who can only be trusted to act in his own self-interest. (Nick Bartlett)

Asami Yamazaki in Audition

For two thirds of its runtime, Takashi Miike's brilliant "Audition" plays out like a romantic comedy, as a widower, Shigeharu (Ryo Ishibashi), searches for a new wife by holding auditions for a film he has no intention of making. But when he meets the enigmatic Asami, he falls head over heels in love, and immediately settles on her, much to the disbelief of his colleague, who finds her a little unsettling.

Former model Eihi Shiina lends Asami an ethereal quality that can either be read as angelic or unnatural. The audience catches a glimpse of her true nature early on in a truly disturbing brief scene involving a phone and a burlap sack, but it's only in the film's final half-hour that the nightmare truly begins. While on the surface, Asami Yamazaki is one of the most unsettling movie villains out there, once you dig a little deeper you discover she's a lot more complicated than she first appears. To reveal too much would ruin the film, but suffice to say the sing-song way she says "Kiri-kiri-kiri" will stay with you weeks later. (Nick Bartlett)

Charles Oakley in Shadow of a Doubt

One of my favorite elements about the films of Alfred Hitchcock is the way he forces his audience to sympathize with his villains. It's there in the moment the car doesn't sink in the bog in "Psycho," Bruno reaching for the fateful lighter in "Strangers on a Train," or Rusk retrieving his tie pin in "Frenzy."

Even with this in mind, there are few Hitchcock villains who lay out their entire raison d'etre in the same way as Joseph Cotten in "Shadow of a Doubt." The scene where "Uncle Charlie" talks about his hatred of rich widows at the dinner table is one of the most scarily insightful depictions of a murderer that we'd seen up to that point (the closest comparison might be Peter Lorre in "M") and is a sharp contrast to the friendly persona he outwardly projects to his unsuspecting family.

Cotten gives a suave and charming performance, and Hitchcock wisely never shows him committing any murders, so our sympathy remains divided throughout the film — even when he tries to murder his suspicious niece (Theresa Wright) in a series of "accidents" we don't see him set up. It's easy to sympathize with a killer if he's played by Joseph Cotten and you never see him actually kill anyone. It's harder once you're confronted with their actions, as we are in the film's final moments where he tries to throw his niece from a moving train. (Nick Bartlett)

Magua in The Last of the Mohicans

"The Last of the Mohicans" isn't talked about enough anymore, suffering from the usual Michael Mann problems like paper-thin characterization for the protagonists. But where the movie shines is in the casting of its antagonist. As the Huron chief consumed by vengeance, Wes Studi gives a nuanced performance, perfectly exhibiting his contempt and hatred for the English people. He pledges to eat the heart of "The Greyhair" who destroyed his village and ending his line by killing his daughters.

Magua is a cold, clinical character, but Studi's intense performance is incredibly layered; he's not a monster, just someone who is motivated purely by hatred. At times he appears less an outright villain than an anti-hero, albeit one who goes to further extremes than what we might expect. It's Magua who propels the story forward, while the heroes are mainly reacting to the situations around them. He never betrays the slightest emotion as he hunts down the heroes (at least until the very end, and even then it remains enigmatic) effortlessly killing those who get in his way. He nearly succeeds in his task as well, leading a devastating ambush on the British army and finally killing Munro — and true to his word, cutting out his heart, although we don't see him actually eat it. (Nick Bartlett)

Kakihara in Ichi the Killer

One of the most extreme, controversial films ever made, Takashi Miike's "Ichi the Killer" is a vividly gory film, one that is much better than its sensational reputation might suggest. Tadanobu Asano plays the stiletto-wielding yakuza Kakihara. Trying to locate his boss, he is quickly sidetracked by the titular Ichi, who he mistakenly believes is the ultimate sadist (in fact Ichi is a childlike murderer, provoked into fits of extreme violence).

The embodiment of Miike's punk aesthetic, Kakihara is an iconic villain, dressed in loud, garish outfits, with bleach blonde hair and self-inflicted scars across his face, casually blowing cigarette smoke through the slits in his cheeks. Asano makes his character macabrely funny, with a softly spoken, polite way of delivering his lines, that contrast with his sadomasochistic nature — he can only derive pleasure from intense pain.

Kakihara is searching for what he hopes will be a new kind of pain, but he doesn't mind inflicting all manner of tortures on those who stand between him and Ichi in the meantime. In one case, he extracts information from one unfortunate with the use of fish hooks, tempura, and boiling oil. It's a horrific scene but one undercut by Kakihara's casual description of it as "just a little torture." As the film builds towards the pair's inevitable showdown, Kakihara becomes almost childishly delighted at how scared he is getting at the prospect of facing Ichi, feeling genuine fear for the first time in years. (Nick Bartlett)

Frank Booth in Blue Velvet

While some people might think the best villains are the ones in control or super-intelligent, often it's those who lose control that are the scariest.

In David Lynch's "Blue Velvet," Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) is a terrifying villain principally because he has no self-control, no restraint. He's a psychopath who inhales a mystery gas through an oxygen mask (although Hopper later claimed it was amyl nitrate) that turns him into a giggling, frenzied maniac. Alternating between sobbing in Dorothy's (Isabella Rosselini) lap to beating and brutally raping her, he is a truly monstrous character.

Frank is an outlandish character, and one who's also funny and weirdly vulnerable, and is all the scarier for it. These contrasts should be jarring, but because Hopper fully inhabits the role, and never shies away from the extreme aspects of his character, it works. His frequent usage of the F-bomb (in pretty much every line) is hilarious, and his childlike screeches of "Pretty! Pretty!" as he huffs gas in the final scene is one of the creepiest moments in cinema. Also, you'll never listen to Roy Orbison the same way again. (Nick Bartlett)

Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest

It might seem odd to include the antagonist from "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" in a list of the best film villains of all time. She doesn't kill anyone or order anyone's death. She only indirectly causes the death of one character towards the very end of the film, yet she might be the most reprehensible character on this list.

As written in Ken Kesey's novel, the controlling chief nurse is a grotesque character, and later incarnations have leaned into larger-than-life, almost campy portrayals. However, the genius of Louise Fletcher's performance is how softly spoken and friendly she initially appears. It's only when her authority is challenged by new patient McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) that we start to see her darker side. As McMurphy questions her rules and encourages his fellow patients to stand up for themselves, Ratched is ruffled (the flushed look of indignation she flashes at McMurphy when he uses her Christian name is incredibly telling) and uses increasingly extreme methods to reassert her influence over the group, even going so far as sending McMurphy to electro-shock treatment.

This all culminates in the film's ending, where we see how twisted her controlling nature is. Her callous treatment of poor Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif) is unspeakably cruel — she knows what will likely happen, and Fletcher's calm, measured delivery makes it all the more chilling. (Nick Bartlett)

Rene Belloq in Raiders of the Lost Ark

"Raiders of the Lost Ark" towers over the other films in the "Indiana Jones" film series. It features the best heroine, the best sidekick, and undeniably the best villain in Rene Belloq. None of the antagonists who followed could possibly have measured up to Paul Freeman's suave French archaeologist.

The ultimate "shadowy reflection" of the hero, Belloq is a very different character to Jones, more arrogant and mercurial, but more than a match for him intellectually. Their relationship is best summed up by the opening sequence; while Jones throws himself into the physical side of things (dodging arrows, swinging across ravines, outrunning a boulder), Belloq simply ingratiates himself with the Hovitos, having learned their language, and strolls off with the idol — but not before ordering the Hovitos to kill Jones.

Where they differ is in ideologies: While Jones is an idealist, Belloq is more than happy to align himself with whoever can help get him what he wants. In this case, the Nazis, and while he comfortably allies himself with them, you get the sense he sees them as a means to an end, as is evident in his final scene with General Dietrich (Wolf Kahler), where the power balance has completely shifted. Belloq intended to use the transmitter to his own ends before handing it over to the Nazis, but it's this arrogance that proves his undoing. (Nick Bartlett)

Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men

The Coen Brothers have no shortage of great villains in their back catalog, from the gangsters of "Miller's Crossing" to Peter Stormare's psychotic kidnapper in "Fargo." None, however, are quite so terrifying as Javier Bardem's mercenary in "No Country for Old Men," who always appears seemingly from nowhere, as inevitable as fate.

Operating in the shadows, and with a warped sense of honor, Chigurh is a nightmarish villain who cannot be reasoned with. Murdering countless innocents in his pursuit of the money found by Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), there are any number of scenes that demonstrate his psychopathic nature. One of the creepiest moments, though, is when he corners Woody Harrelson's fellow mercenary. As Harrelson attempts to bargain for his life, Chigurh looks fascinated by him, as if he's a different species. He almost laughs at him, but it's a laugh without any real emotion behind it, he's just toying with Harrelson and relishing the fear that is dripping off his old acquaintance.

Chigurh might not be superhuman, but he does feel almost supernatural in his manner and his innate ability to sense danger. (Nick Bartlett)

Hannibal Lecter in Manhunter and Silence of the Lambs

The breakout character from Thomas Harris' "Red Dragon" novel, Hannibal Lecter is the only villain on this list where we're including two depictions of the same character: Brian Cox in Michael Mann's "Manhunter" and Anthony Hopkins' Oscar-winning performance in "The Silence of the Lambs," both as the cannibal Hannibal Lecter.

Both depictions have pros and cons. Brian Cox underplays his Lecter (or Lecktor) making him an all too realistic character, one who engages in genial patter with FBI agent Will Graham (William Peterson) before casually asking for his home phone number. It's a chilling moment, as is the way he casually manages to get hold of Will's address when supposedly talking to his lawyer, and contrasts with the barbarity of his letter to "The Tooth Fairy." Cox is brilliantly deadpan in the role, but suffers from very limited screen time.

Hopkins is rightfully celebrated, but it has to be said he veers on pantomime in places, especially when leaning too far into his Truman Capote impression. The moments where we see the monster that lurks below the facade are truly terrifying though, such as his escape from his holding cell and his first appearance. The way Hopkins lies in wait in his cell and stares unblinkingly into the camera lens and the audience's soul is genuinely unnerving — and the perfect introduction to the character. (Nick Bartlett)

Hans Gruber in Die Hard

Steven E. de Souza, the co-screenwriter of "Die Hard," has said himself that Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) is the film's real protagonist, and it's John McClane (Bruce Willis) who disrupts proceedings. It's an argument that makes a lot of sense: Gruber doesn't just exist to chase after McClane; he has his own objectives, as we see in his genuine concern once McClane steals the detonators. Unlike the lackluster villains in the sequels, Gruber is able to constantly think on his feet and alter his plan accordingly, as he does once he comes face to face with McClane.

In his big-screen debut, Rickman gives a charismatic, frankly masterful performance that elevates the rest of the film, and made a lasting impression on the way genre villains were written. Originally conceived as more of a physical threat to McClane — the whole character changed upon the casting of Rickman. Instead of a mercenary, he was repurposed as a debonair, dryly witty criminal mastermind who can out-think the hero rather than fight him.

Rickman makes Gruber both charming and utterly ruthless, not hesitating to murder hostages in cold blood (and actually, murdering hostages is a necessary part of the plan). This is undoubtedly Rickman's most iconic role, and one that had him typecast as the villain for the rest of his career. (Nick Bartlett)

Captain Vidal in Pan's Labyrinth

Guillermo del Toro's villains are often representatives of fascism, from the barbaric Jacinto in "The Devil's Backbone" to the stiff Colonel Strickland in "The Shape Of Water," but none so fully embody the ideals of fascism than the humorless Captain Vidal in "Pan's Labyrinth." Set in the midst of the Franco Spanish civil war, Vidal is introduced as the emotionless new stepfather of Ofelia, who has been tasked with hunting down the Republican rebels hiding in the hills.

Sergi Lopez makes an incredibly sinister, imposing villain. Immaculately dressed in a spotless uniform and perfectly shined boots, Vidal runs his household regimented and disciplined to a fault, the same way he runs his division. Obsessed with rules and regulations, the first time he meets his new stepdaughter, he refuses to shake her hand, instead instructing her how to do it correctly. The most disturbing thing about him is the way he never breaks composure. In one scene he beats a suspected rebel to death with a wine bottle and barely breaks a sweat, and only scolds his underling a little when it emerges the man was completely innocent.

Del Toro's most fully-realized villain, Vidal is a terrifying, monstrous creation, and brilliantly brought to life by Lopez. (Nick Bartlett)

Norman Stansfield in León: The Professional

Gary Oldman has played more than his fair share of iconic film villains – in "True Romance," "Air Force One," and "Bram Stoker's Dracula" to name a few. But it's his scenery-munching turn as the corrupt, Beethoven-loving Detective Stansfield in "Léon: The Professional" that remains his most memorable and fully fleshed-out baddie.

The complete inverse of his morally upright Jim Gordon in "The Dark Knight" trilogy, Stansfield is a villain through and through. Addicted to his mysterious pills, and not averse to murdering an entire family to make a point, he's the polar opposite of the film's hero, the hitman Leon (Jean Reno). While Leon is manic and introverted, Stansfield is all frenzied energy and prone to histrionics (his bellowing of "EVERYONE!" is just incredible), and their contrast is further exemplified by their respective costumes. While Leon dresses primarily in black, Stansfield is entirely decked out in light colors, the inverse of the usual goodie-baddie look.

While Oldman's performance often veers over the top, he is a genuinely sinister character, as shown in the scene where he menaces Mathilda (Natalie Portman) in the police station. Oldman brings an unnerving intensity to Stansfield even in his quieter scenes, and his fate is one of the most satisfying on this list. (Nick Bartlett)

Harry Powell in The Night of the Hunter

Charles Laughton's only outing as a director is one of the best scary movies directed by an actor, making for a singularly terrifying piece of cinema. A fairytale mixture of American gothic and film noir, "The Night of the Hunter" follows two orphaned children relentlessly pursued across the country by the murderous preacher Harry Powell, who follows his own version of Christianity that, as he puts it, "the Almighty and me worked out betwixt us."

Robert Mitchum might be best remembered for his portrayal of Max Cady in the original "Cape Fear," but for our money, it's his idiosyncratic turn as Powell that remains his defining film performance. He's an iconic figure, with "Love" and "Hate" tattooed on his knuckles, and spouting Bible verses to gullible townsfolk, all the while murdering women without compunction, and threatening to kill the children as he attempts to locate the $10,000 hidden by their father.

Shot in such a way that he is both imposing and cartoonish, his constant refrain of "Children, oh children" is truly spine chilling, as is the hymn he sings to himself, that lends him an almost supernatural air as he tracks the children day and night. The monstrous scream he emits as they escape onto the river is the stuff of nightmares. (Nick Bartlett)

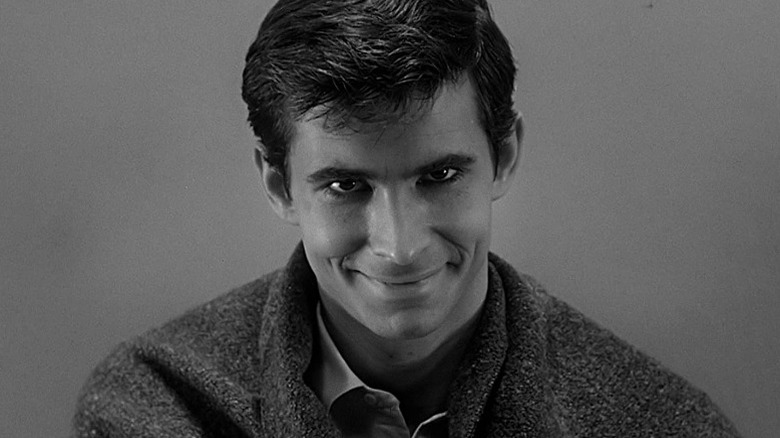

Norman Bates in Psycho

It's well-known that "Psycho" was based on the true story of Ed Gein, the real-life murderer who served as the basis for "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre," "The Silence of the Lambs," and "Henry: Portrait Of A Serial Killer," among others. But where Hitchcock's film differs from these is in the depiction of the killer. Instead of a heavy-hitter, Hitchcock cast preppy, bookish Anthony Perkins as the repressed Norman Bates — 100 miles away from the middle-aged, balding character from Robert Bloch's book — and used the actor's affable charisma to lull the audience into a false sense of security.

Perkins makes Norman a likable, if awkwardly intense figure from his very first interaction with Marion Crane (Janet Leigh). Even when we see glimpses of his darker nature (spying on Marion in the shower) it's difficult to believe Norman is a killer. He seems altogether too hapless, as if he "wouldn't hurt a fly," which makes the final reveal all the more spine-chilling. Because, of course, it's not Norman who commits the murders — it's his dead, domineering mother, who has taken over at least a portion of Norman's mind.

Perkins was typecast for the rest of his career (even playing Norman twice more) but said that even if he had the choice again, he'd still take the role. It's one of cinema's greatest performances, and that final, fourth-wall-breaking moment remains incredibly unsettling to this day. (Nick Bartlett)

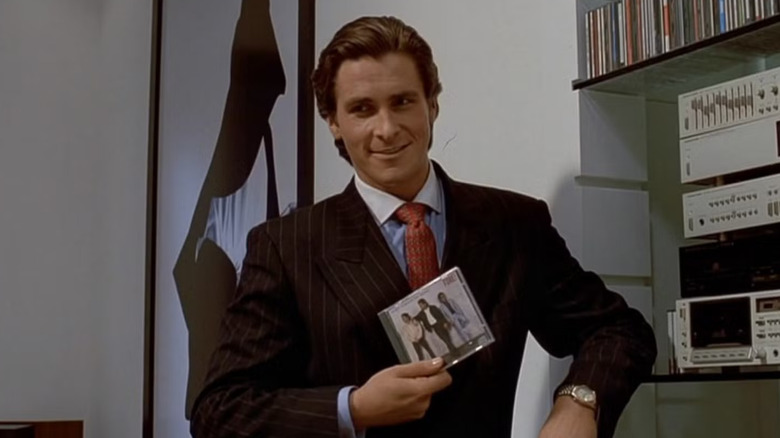

Patrick Bateman in American Psycho

Though Patrick Bateman might be the protagonist of "American Psycho," he's still one of the most brilliantly horrifying villains ever seen on screen – even if the film's ending leaves us to wonder if he was anything more than a delusional banker. Bateman's acts throughout the story are so vile that the book was thought by some to be unfilmable; yet he was so psychologically arresting — with his bizarrely insecure personality, hilarious obsession with looks and pop culture, and dry, dark sense of humor — that co-writer and director Mary Harron had to try.

As well written as the character was, it was nearly impossible to find a star to take it on. Many famous actors turned "American Psycho" down, including Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, and Leonardo DiCaprio. Harron successfully lobbied the studio to let her cast a then-unknown Christian Bale, who was subsequently warned that playing Patrick Bateman would end his career before it began. He didn't seem to mind, and didn't even notice when his peculiar performance on set had his co-stars thinking he sucked at acting. In actuality, Bale played Bateman so unnaturally on purpose — with Harron, he recreated the murderer as a sort-of alien, so detached from his own humanity and the emotions of others that basic social interactions were foreign, needing to be calculated and dissected through the constant running commentary in his mind.

When the film was released, Bateman turned Bale into a star — and got him some worrying praise from the Wall Street traders he was meant to satirize. Over 25 years later, audiences still want more from him, and, indeed, "Elvis" star Austin Butler and director Luca Guadagnino are set to give them just that. For now, Christian Bale's Patrick Bateman is too hip to be square, even when he's killing people. (Russell Murray)

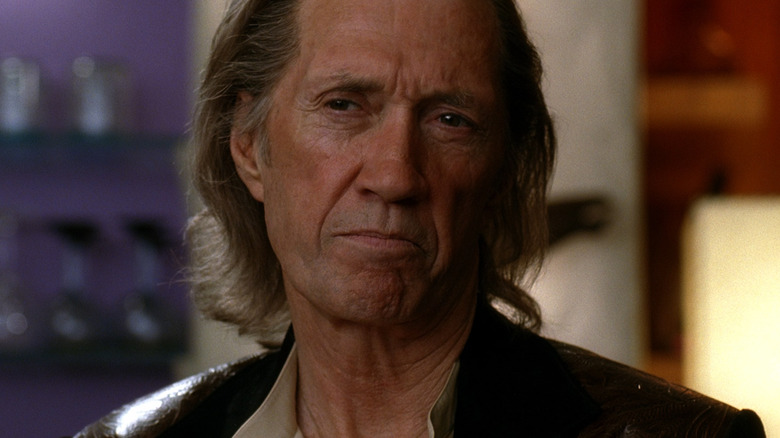

Bill from Kill Bill

It takes careful writing, intentional directing, and the talent of a superior actor to make a villain have presence even when they aren't on screen. That's precisely what makes David Carradine's titular bad guy from "Kill Bill" so exceptional in its execution, performance, and impact.

After seemingly murdering the Bride (Uma Thurman), her groom, and the wedding party in the opening scene of "Kill Bill: Volume 1," the scorned leader of the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad vanishes for much of the vengeful plot. And yet, just from hearing his voice off-screen in two brief but powerful moments, he carries so much weight heading into the saga's second part. It's perhaps his strategic, sparse use throughout that gives Bill such gravitas when he does finally appear.

Though Carradine went through all the same brutal martial arts training as the rest of the cast — and even had a cut scene where he used said training on none other than Michael Jai White — Bill's scenes in "Volume 2" are almost all dialogue based. When presented with its ultimate villain, "Kill Bill" subversively switches up the pace and renders conflict through tender, intimate conversation about morality and love, which pack an even more emotional punch after several hours of gory fight sequences. Bill's use is a massive part of what makes "Kill Bill" an action saga like no other. (Russell Murray)

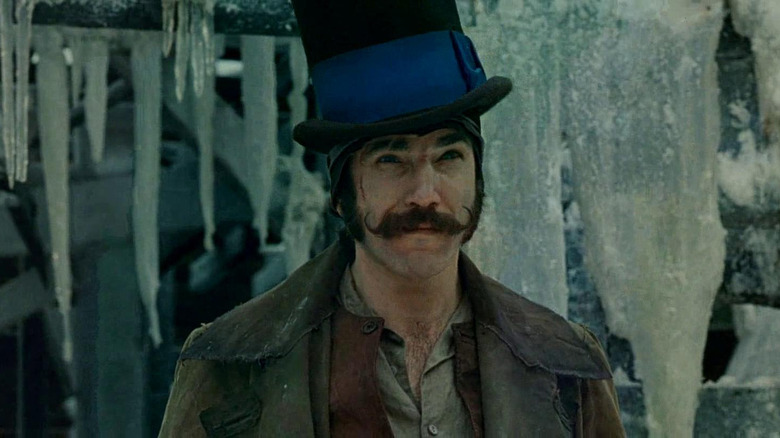

Bill The Butcher Cutting in Gangs of New York

Martin Scorsese's "Gangs of New York" is as infamous for its debated place in his filmography among cinephiles and Daniel Day-Lewis is for his method acting technique. The legendary Academy Award-winner starred as ruthless gang leader Bill "The Butcher" Cutting in the 2002 historical epic, opposite Leonardo DiCaprio as vengeful would-be gangster Amsterdam Vallon.

Day-Lewis fiercely tackled this killer role with meticulous preparation and dedication, pushing DiCaprio to the limits of what he thought he could do as an actor. When there were stunts, Day-Lewis did them; between scenes, if he wasn't fighting in-character with DiCaprio, he would wander the snowy streets of Rome in period-appropriate winter wear looking for fights with strangers — while he didn't catch any fists, he did catch a nasty case of pneumonia, which he insisted on only being treated with period-appropriate remedies. (How listening to Eminem's "The Way I Am" every morning fits into this method, we can only guess.)

As insane as this all sounds, Day-Lewis' no-holds-barred approach served the Herculean effort of transforming Bill from a relatively underwhelmingly scripted Scorsese character into a force of nature. You can feel the actor's deranged commitment in every scene, creating a sense of danger that almost feels too real. (Russell Murray)

Le Chiffre in Casino Royale

It's hard to imagine a time before Mads Mikkelsen became one of Hollywood's go-to villains — though we can pinpoint the period to just about before the release of "Casino Royale" in 2006. The "Hannibal" star was cast as a relatively unknown actor for the "James Bond" reboot film, which was largely aiming to launch Daniel Craig's tenure as cinema's favorite super spy. For the role of Le Chiffre — a genius criminal, banker, and poker player who competes against Bond in a card game of life and death — the creative team originally had a different actor cast and ready to shoot.

But when the actor had to drop out, Mikkelsen was able to step in serendipitously, as he happened to be in Prague where they were filming. That this last minute change ultimately resulted in one of the greatest "Bond" villains of all time is not merely a testament to fortune, but rather to the craft of the screenwriters and Mikkelsen's empathetic yet lethal performance as Le Chiffre. Whether sitting across from Bond at a poker table or standing over him as a heartless torturer, Le Chiffre is chillingly human. His dynamic, captivating presence throughout the film is just one reason why "Casino Royale" is arguably the best "James Bond" movie ever made. (Russell Murray)

The Joker in The Dark Knight

Back when Christopher Nolan was trying to discover who would take on the role of Bruce Wayne in his "Batman" reboot, he met with a great number of Hollywood leading men — including Heath Ledger. Observing the contemporary landscape of superhero films at the time, the actor understandably declined. It wasn't until after the release of "Batman Begins" that Nolan's vision for his films became clear — adult, psychologically complex crime thrillers based firmly in the real world, with talented actors imbuing literally two-dimensional characters with novel humanity. It was through this lens that Ledger found his way to playing the Joker in "The Dark Knight."

The iconic "Batman" villain — famous for his unnerving flamboyant demeanor in the face of danger, unrelenting cruelty, and ingenious ability to blend elements of humor and horror — was a necessary part of Nolan's reimagining. But Ledger did much more than dutifully translate the character from page to screen. All the elements one would expect are there, as are the gritty, popularized tropes of the gleefully deranged serial criminal pioneered by "A Clockwork Orange." In addition, however, Ledger used his own self-doubt and anxiety to render these emboldening character traits within a vessel that felt disturbingly real due to his vulnerability.

There's a nervous energy that pervades every scene, convincingly creating the atmosphere that the Joker would do anything if anyone makes the wrong move. (Plus, that terrifying voice still can't be beat.) This made him the perfect foil for Christian Bale's Bat of Action, resulting in a villain so perfect yet unusual that even on set the cast knew it would land — especially Ledger. In fact, "The Dark Knight" so changed his perspective on superhero films that Ledger made plans to return as the Joker for a sequel before his death. (Russell Murray)

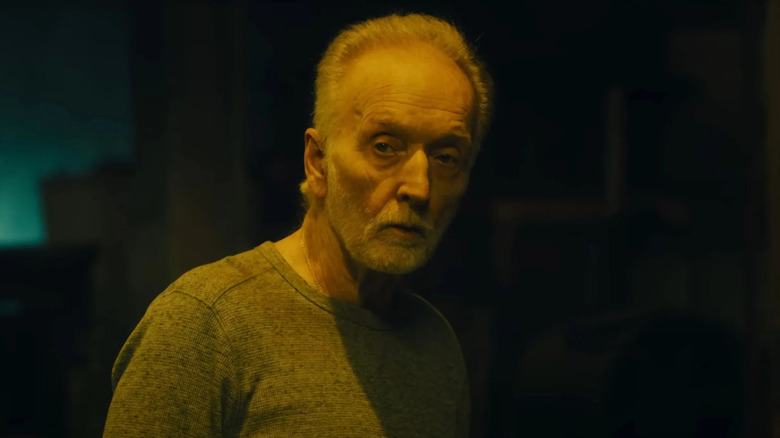

John Kramer in Saw

Most movie villains don't tend to become more effective after they've apparently been killed. Strangely enough, this isn't true in the case of John Kramer.

Bell first played Kramer in the original 2004 "Saw," which presents him for the most part as an innocent, elderly cancer patient and/or a bloody corpse by hiding his villainy behind Billy the Puppet. The final twist that Kramer had been alive the whole time, pulling the strings from the past through carefully plotted games and psychological manipulations, remains one of the greatest horror movie twists of all time. Once "Saw" proved to be a hit among the genre crowd, Lionsgate set out to produce as many of them in quick succession as possible, with various writers and directors coming in and out of the fray to tell a strangely ambitious, soap-opera-like story centered around Kramer and the expanding cult of Jigsaw.

Bell saw the high-stakes-drama the filmmakers were going for, and turned Kramer into a passionate, tragic mastermind through a committed performance that wouldn't be out of place in a Shakespearean drama. Even after Kramer was killed off in "Saw III," the producers were so invested in his character that they immediately regretted the decision, and thus went about creating a messy timeline just to keep Kramer and Bell around as long as possible. (Russell Murray)

Castor Troy in Face/Off

A great cinematic villain is often made by the performance of an actor. In the case of "Face/Off," it was made by two.

In the 1997 John Woo action thriller, an FBI agent uses experimental technology to literally trade faces with a psychopathic terrorist by the name of Castor Troy. Troy is originally played by Nicolas Cage, giving a performance so fearlessly unhinged that even he thinks it was a bit much in hindsight. Once the faces are swapped, however, Cage takes on the role of FBI agent Sean Archer as he impersonates Troy ("a dude playing another dude," etc.). John Travolta, meanwhile, who originally played the real Sean Archer, takes over as Troy once the criminal manages to steal his opponent's face.

This dynamic alone makes for two of the most compelling villainous performances on this list, with Cage and Travolta — two of Hollywood's most ridiculously over-the-top actors — seemingly trying to out-crazy one another for the entire runtime. Troy in any other story, executed any other way, might be a forgettable Hans Gruber clone. In "Face/Off," Woo, Cage, and Travolta make him one of the most unique and memorable characters in the action genre at large. (Russell Murray)

Martin Vanger in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

The Skarsgård acting dynasty has given us more nightmares on film than we'd like to remember. But even amongst the likes of Pennywise the Clown, the most disturbing performance among them all might well belong to Stellan Skarsgård for playing Martin Vanger in the 2011 adaptation of "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo."

Directed by David Fincher, the film is endlessly upsetting and unsettling, even as it arrests the viewer with an ever-unfolding mystery surrounding the disappearance of a young girl. The man behind her disappearance is eventually revealed to be Vanger, at first a plausibly charming CEO. However, when journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Daniel Craig) manages to uncover that he has committed decades' worth of racially motivated killings and sexual assaults, Vanger confesses to his captive accuser in such a nonchalant, matter-of-fact way that his evil becomes unmistakable. On paper and in performance, a familiar villainous monologue transforms into something darker from the lips of Skarsgård's character — a challenge, perhaps, that such vileness is not only real, but may be lurking underneath the surface of those we'd never suspect. (Russell Murray)

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

August Walker in Mission: Impossible -- Fallout

From the first moment audiences saw Henry Cavill as August Walker, cocking his arms in the legendary "Friction" trailer for the "Mission: Impossible — Fallout," even a flash of a hulking, fearsome Cavill playing a ruthlessly effective action villain was a total revelation.

Cavill's work is so embodied, seamless, and understated that he doesn't get enough credit for what he accomplished in "Fallout." Filming a "Mission: Impossible" movie at all is a feat of performance and physical exertion, as star Tom Cruise has seemingly inspired the cast to at least try to keep up with his insane feats of stunt work (even if it makes them all blind with pain). The previously referenced bathroom fight scene took an uncomfortably long time for Cruise, Cavill, and stuntman/Wu Shu champion Liang Yang to execute — four weeks of non-stop fighting, to be exact.

Filming the climactic helicopter chase, which Cavill describes as the most difficult scene of his career, was even more challenging and genuinely painful. But this level of determination is so obvious on screen and instrumental to Walker's characterization as a relentless match for Cruise's Ethan Hunt that writer-director Christopher McQuarrie felt it changed the way the character is written. He isn't just an antagonist, but a co-leading man rivaling Cruise's on-screen presence. (Russell Murray)

Annie Wilkes in Misery

Whether rendered through words in the pages of a novel or the performance of an actor on the screen, nobody crafts a villain like Stephen King. The globally beloved horror writer has earned acclaim and adoration through his iconic bibliography — a reality that inspired a strange sense of fear within King that eventually turned into the villain of his 1987 novel "Misery."

The story — which was adapted into a film by director Rob Reiner and screenwriter William Goldman in 1990 — follows the psychological torture exacted upon a famous writer (played by James Caan in the film) by a fan holding him captive in her isolated Colorado home. This fan is Annie Wilkes, a nuanced horror villain whose many layers are subtly teased throughout the film. She's played by Kathy Bates, who plays Wilkes by oscillating between total delusion and deep sadness, brought on by a pervasive and tragic awareness of her own mental condition. Her work in the film was met with praise, though when Bates went to Reiner about campaigning for Best Actress he warned her the Academy would never give a horror film its flowers – she proved him wrong and took home the Oscar.

Wilkes is probably best remembered for the infamous "hobbling" scene, one of the scariest moments in a Stephen King film that even scared off "Misery's" first director. But it's the combination of these shocking moments with Bates' performance that make Wilkes feel so tangible as a character — which, in turn, makes her one of the most terrifying Stephen King villains we've seen on screen. (Russell Murray)