Our 15 Favorite Underrated Film Noirs

Film Noir is a notoriously difficult genre to pin down, in that nobody can give an entirely comprehensive definition of what it is. Everyone can list examples and recurring traits — the femme fatale, hard-boiled dialogue, and chiaroscuro cinematography, but ask 10 people to define it and you'll get 10 different answers.

The problem with compiling a list of the best films like this is that there will never be any new entries. It's invariably the same titles that occupy the top positions — "Double Indemnity," "Touch Of Evil" and "The Big Sleep," just to name a few.

You can't argue with this because they're all excellent choices, but it does mean that certain films are nearly always neglected. Below are some movies that are underrated in this respect. Many are held in high esteem by movie buffs, but you'll rarely find them in Top 10 lists.

Born To Kill

"Born To Kill" might be the single nastiest noir of the classic era — directed by the man who would go on to direct "The Sound Of Music," no less! In a genre full of sadistic, amoral anti-heroes, Sam Wilde (Lawrence Tierney) is the nastiest of them all. Tierney was a nightmare of an actor by all accounts, but he is perfectly cast here, playing a pure psychopath who finds a kindred spirit in Claire Trevor's sociopathic socialite.

Sam is a terrifyingly unpredictable character, and his brutal murder of both his romantic rival and the girl they were fighting over makes for distressing viewing. With the amount of violence and general seediness on display, it's a wonder this even got made during the days of the production code. The twisted relationship between Tierney and Trevor is especially depraved, as they make leery faces at each other behind the backs of their wholesome partners. Walter Slezak is great as the twinkly-eyed, literate private eye, and Elisha Cook Jr is as wonderful as ever as Sam's creepy roommate (the scene where he charms a potential murder victim is truly skin-crawling stuff).

Woman On The Run

"So, Frank's a fugitive from the law? Well, that's just like him."

A much lighter affair, this film earns a spot on the list due to Ann Sheridan's wry, sardonic performance as the laconic Eleanor, the wife of a witness to a murder. Sheridan is excellent, and it's refreshing to have a female lead who is neither a femme fatale nor a damsel in distress driving the story forward in the search for her husband.

While she's initially indifferent to her husband's disappearance, he leaves clues to his location specific to their romantic history, and the nostalgic trail of breadcrumbs gradually cuts through Eleanor's cold exterior and reignites her love for her husband.

She's assisted in her search by Dennis O'Keefe's enigmatic but charming newspaperman, and there's a wry playfulness in their scenes together, accompanied by a real sense of menace as potential witnesses keep getting murdered. Norman Foster's direction is light but assured, effectively directing both a serious noir and a witty, heartwarming love story. The twist is neat and subversive, and the supporting cast is uniformly excellent – especially Robert Keith's grumpy lead detective.

He Walked By Night

The documentary thriller was a fertile subgenre of the classic noir era — films like "T-Men" and "The Naked City" show the apparent mundanity of police work, and laid the groundwork for police procedurals today. "He Walked By Night" is different, mainly because it forces the audience to identify with a cold-hearted, ruthless killer, and shows him to constantly outmaneuver the cops on his tail.

Richard Basehart gives an impassive, cold performance as the fugitive, in a part that could have been a major influence on "Le Samourai" and "Drive" — although neither of the leads in those films is quite as ruthless.

Predating "The Third Man" and its beautifully shot chase sequence by about a year, Alfred L Werker and an uncredited Anthony Mann execute an uncannily similar finale as Basehart desperately flees the police through a series of underground sewer tunnels. John Alton's cinematography proved one of the defining features of noir, and he makes excellent use of silhouettes and shadows, creating a striking look for the film.

The Prowler

Joseph Losey's dark character piece is decidedly B-movie stuff, but it's an especially potent slice of Film Noir all the same. Written by Dalton Trumbo just as the blacklist was coming into force (which might explain the cynical depiction of law enforcement as corrupt or incompetent), it stars Van Heflin as an unrepentantly amoral uniform cop. When a local prowler causes trouble and Heflin's cop is called to attend the crime scene, he immediately falls for the lady of the house (Evelyn Keyes). The two begin a love affair and he quickly devises a plan to get rid of her husband.

Often feeling like an inverted "Double Indemnity" with Heflin playing the tempter and Keyes the gullible accomplice,"The Prowler" is a deeply unpleasant film, and a precursor to films like "Blue Velvet," where the idyllic suburbs conceals a dark underbelly. Aside from Heflin's truly abhorrent character, the rest of the film's characters (including his comically credulous partner) are played with the sort of small-town decency that makes his actions all the more obscene by contrast. The film gets seedier as it goes on, culminating in a genuinely tense climax in the desert.

The Narrow Margin

Forget the remake with Gene Hackman, this is one of the tensest, tightest Film Noirs ever made. FBI agent Charles McGraw is assigned to protect a gangster moll turned government witness (Marie Windsor). As they travel back to headquarters by train, the gangsters close in on them, and when McGraw searches for an ally on the train, he finds nobody is what they seem.

Marie Windsor played an iconic femme fatale in "The Killing," but is even better here as the tough-as-nails witness who is openly hostile, never softening her character. McGraw, so good as one of the titular hitmen in "The Killers," is a little too straitlaced, but it hardly matters when the rest of the film is so much fun. It's full of witty dialogue and narrative twists that are genuinely surprising (which is something of a rarity in older films), and features memorable roles for the supporting cast — most notably Peter Virgo as the hitman and Paul Maxey as the overweight passenger who gets the immortal line: "Nobody loves a fat man except his grocer and his tailor!"

The Breaking Point

Ernest Hemingway's "To Have And Have Not" already had a definitive movie adaptation thanks to Howard Hawks when Michael Curtiz made "The Breaking Point." Hawks' film features quotable dialogue, palpable sexual chemistry between Bogart and Bacall, and catchy songs. However, it bears so little resemblance to the source material that John Huston was able to steal the book's ending for his own "Key Largo" without anybody noticing!

Curtiz's adaptation is far truer to the original novel. Gone are the upbeat songs and irreverent tone, and in its place is an oppressive hopelessness that swallows up every character that inhabits the film. It's a lot more noirish than Hawks' movie, and relentlessly bleak, with John Garfield as the struggling fisherman forced to take on illegal jobs to pay the bills.

Garfield might not be as iconic as Bogart, but he gives an effortlessly grounded, natural performance here. Patricia Neal is well cast as a wry inversion of the femme fatale, Wallace Ford is wonderfully sleazy as the shady lawyer, and Phyllis Thaxter is touching as Garfield's loyal wife — their relationship is the only one in the film that's left untainted. The final shoot-out is nail-biting stuff, and it has one of the most cynical, bittersweet endings of the genre.

The Set-Up

Robert Ryan might be the definitive noir actor, a guy who could deploy his chiseled looks and imposing stature to depict either troubled heroes or malevolent villains. Here he gives a tragic, touching performance as Stoker Thompson, an over-the-hill boxer. So certain is his manager that he will lose his upcoming bout that he takes a pay off from the local gangster to throw the fight. But nobody tells Stoker this, and against all odds, he begins to win.

Around Ryan's beautifully observed, touching performance, Robert Wise populates his film with bloodthirsty punters who long to see Stoker beaten, from a blind man whose friend provides a running commentary to the mousy housewife who goes from reluctant attendee to the most vocal of the bunch, screaming for the boxers to kill each other.

One of the greatest boxing films of all time and Ryan's favorite role of his career, the actor gives a raw, dignified performance full of pathos. It helps that he could actually box in real life, having been a champion at college, and he makes his character authentic and lived in. Audrey Totter is wonderfully humane as Stoker's despairing wife, who refuses to watch the fights and longs for him to quit. Their final exchange is both heartwarming and devastating, encapsulating the film's bittersweet tone in one line of dialogue.

Shield For Murder

Edmond O'Brien might be the most overlooked noir actor. He was ostensibly the lead in both "White Heat" and "The Killers," but was overshadowed by James Cagney and Burt Lancaster, respectively. "Shield For Murder" (which he co-directed) gives him the rare opportunity to shine, and O'Brien grabs the opportunity with both hands. He is quite simply electric here.

Playing a crooked cop desperate to start over, he gives a dynamic, sweaty, desperate performance, reminiscent of both Richard Widmark in "Night & The City" and Orson Welles in "Touch Of Evil." O'Brien's Barney has no redeeming features, and certainly no compunction about breaking the law. He's corrupt, violent, and thoroughly unpleasant, yet there are also hints of the cop he used to be that make you stop short of hating him altogether.

The final chase and the shootout in a swimming pool are proper tense stuff, and the moment where Barney inflicts a prolonged beating on Claude Akins' hood is truly nasty, as is evident from the onlookers' shocked expressions. An unceremonious, violent thriller with shocking moments and an appropriately abrupt ending, this is noir at its most pulpy and hard-boiled.

Act Of Violence

The Second World War looms large over the Film Noir genre. Several films use the war as an explicit plot point, such as "The Blue Dahlia," "Thieves' Highway," and "Crossfire," but few confront the trauma and long-reaching impact of the war better than Fred Zinnemann's "Act Of Violence."

Van Heflin plays a former POW who is now a pillar of the community, revered as a war hero and living a life of suburban respectability with his beautiful wife (an impossibly young Janet Leigh). That is, until fellow survivor Robert Ryan arrives in town, haunting his every step. Zinnemann wisely cuts to the chase quickly, allowing both actors to explore their characters in more depth — Heflin was no hero, betraying his fellow soldiers and getting them killed, and Ryan is the avenging angel here to settle the score.

A lean, efficient thriller masterfully told, Zinnemann adroitly blurs the lines between hero and villain; both leads give incredible performances as characters who prove to be infinitely more complicated than they first appear. Berry Kroeger is a lot of fun as a sleazy hitman, but best of all is Mary Astor as the alcoholic prostitute who gives a poignant, soulful performance, miles away from her glamorous turn as one of noir's first femme fatales in "The Maltese Falcon."

Raw Deal

While Anthony Mann is best remembered for his westerns, he made his name with a series of hard-boiled noirs. "Raw Deal" is the slickest of all, a dark, lean thriller with a stripped-back script. Pat (Claire Trevor) helps her boyfriend Joe (Dennis O'Keefe) escape prison after he takes the fall in a bank robbery, taking idealistic assistant lawyer Ann (Marsha Hunt) along as a hostage. Complicating matters is O'Keefe's former partner (Raymond Burr), who owes him money from the robbery but is unwilling to pay up, choosing a more permanent solution.

John Alton's striking cinematography makes stunning use of shadows, silhouettes, and lighting, and renders the relatively simple story vibrant, fatalistic, and almost poetic. The fog-lit final sequence is especially beautiful, as is the confrontation at the beach. Burr makes an imposing, sadistic villain, and John Ireland is effortlessly cool as his laconic henchman.

However, it's the central love triangle that makes the film stand out, specifically the insight given by having a female narrator. This is rare in noir, but somehow it's entirely fitting when that character is played by the iconic Claire Trevor. She gives the stand-out performance as the tragically loyal Pat, who recognizes Joe falling in love with Ann before he does.

Odds Against Tomorrow

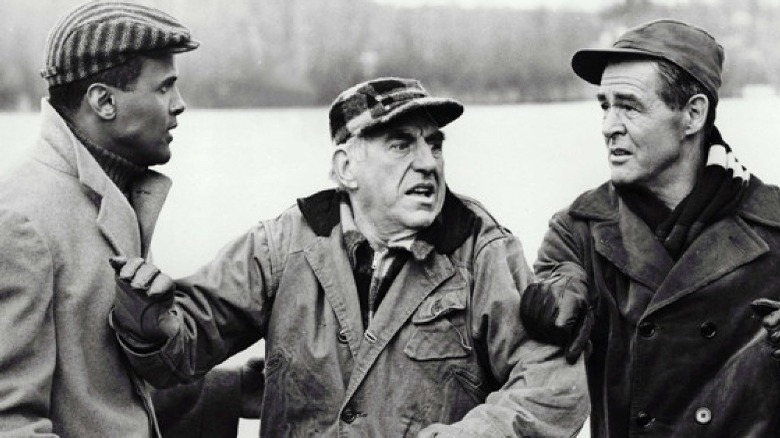

We've discussed this late addition to the genre as a heist film before, but as a piece of noir, it's even more potent. Director Robert Wise takes his time establishing the plight of the main character as we discover each of them at their lowest ebb, and get to know them before they're finally convinced to take part in a bank robbery.

Harry Belafonte gives a surprisingly nuanced turn as the jazz singer hopelessly out of his depth. Even better is Robert Ryan, who David Thomson once called "an actor who seemingly had no wish or need to be liked." It's certainly true of this character, a tightly wound ball of bigoted, impotent rage. When he asserts his masculinity by beating up a marine in a bar, it's not the triumphant moment you might expect, but a pitiful one. Ryan refuses to make his character a one-note racist, though, and he remains decidedly human.

Unapologetically nihilistic, "Odds Against Tomorrow" is way ahead of its time, examining the bitterness that fuels racism in a vivid and nasty way. Abraham Polonsky's harsh, uncompromising dialogue and Wise's excellent direction make this a unique and modern noir. The final coda is both apt and gruesome – the harshest possible way of observing the ultimate futility of racism.

Elevator To The Gallows

Louis Malle's existential debut bridges the gap between classic noir and the early films of the French New Wave. "Elevator To The Gallows" has an irresistible premise: Julien (Maurice Tavernier) has just committed the perfect murder — he's killed the husband of the woman he loves (Jeanne Moreau) so they can be together, but as he tries to make his escape he gets trapped in an elevator. As he waits for the inevitable arrival of the police, we are shown the events that led him to this point via flashback.

Moreau is wonderful as the fading beauty, whose insecurities and paranoia are writ large on her face as she desperately wanders the streets of Paris, slowly becoming convinced that her lover has abandoned her, and the whole thing's set to an iconic, groundbreaking Miles Davis score.

Filmed when Malle was just 24, this is an incredibly mature feature, owing a debt to Alfred Hitchcock, Henri Georges Clouzot, and Julien Duvivier. As with most European noir, there isn't a huge amount of plot here; Malle is more concerned with the internal conflicts of his characters. The ending is devastating, and as with most classic noir, drenched in irony.

Force Of Evil

"All Cain did to Abel was murder him."

A story of illegal numbers rackets made biblical through the elliptical dialogue and the fraternal relationship at its core, "Force Of Evil" occupies a singular place in the genre. John Garfield was never better than he is here as the flashy, corrupt lawyer struck by an unexpected crisis of conscience, while Thomas Gomez looks positively saintly next to him as his small-time bookie brother. The scenes between the two are a joy to watch, with Gomez easily walking away with the film.

There are so many iconic moments, from the audible click on Garfield's telephone letting him know he's being bugged to the final iconic shootout in the dark. An intensely personal project for Polonsky (who was blacklisted shortly after), this is the ultimate testament to his talents.

Polonsky's script is dense without feeling flashy or sacrificing the noirish tone. The dialogue is delivered rapid-fire by a solid cast who hardly even pauses for breath. "Force Of Evil" is a grown-up noir that expects the audience to keep up, and it looks beautiful, with breathtaking location cinematography that still looks impressive today. It's a unique film, perfectly conceived and executed, and deserves wider recognition.

Criss Cross

Robert Siodmak is the unheralded master of noir, and this is his crowning achievement. Burt Lancaster is excellent here, more vulnerable and less gullible than in "The Killers," as is Yvonne DeCarlo as the somewhat reluctant femme fatale (Film Noir maestro Eddie Muller called the shot where DeCarlo looks directly into the camera "noir's defining moment"). DeCarlo's character is interesting in that she isn't overtly manipulative, just opportunistic. That's what makes the story so tragic: They have the potential to be happy, and Lancaster is willing to forget the money if they can be together, but she just can't let it go.

From the moment we meet the central couple almost literally caught in the headlights, their fate is irrevocably sealed as they drift towards the nihilistic ending, and despite a handful of playful moments Siodmak never lets up on the heavy, oppressive atmosphere. The ending is potentially the most emotionally raw of the genre, with even Dan Duryea's silky villain looking visibly shaken.

"The Killers" might have the flashier story, but "Criss Cross" is infinitely more nuanced and infused with a fatalism that really gets under your skin. It's a deeply complex film and one that demands your attention.

Night & The City

"You've got it all ... but you're a dead man, Harry Fabian."

Blacklisted for his communist sympathies, Jules Dassin was effectively exiled to Britain, where he made one of the defining Film Noir movies — and yet one that is rarely listed among the greats. "Night And The City" features stunning location photography, deep focus camerawork to rival Orson Welles, and a kinetic, fast-moving plot that undoubtedly served as an influence on "Uncut Gems."

Richard Widmark gives his greatest film performance as the irrepressible grifter Harry Fabian. Harry is "an artist without an art," constantly wheeling and dealing. Widmark does an impressive job portraying Harry as irredeemably venal (he's introduced stealing from his girlfriend) and still manages to generate empathy from the audience. As despicable as he is, it's impossible to not feel for him, and it's agonizing to watch his dream dissipate in front of his eyes.

The film is full of well-rounded, colorful characters, all infinitely more likable than Harry, with clear and distinct motivations that keep the plot moving in unpredictable ways. Herbert Lom's "villain" is both ruthless and honorable, and the bitterly comic double act of Francis L. Sullivan and Googie Withers is a delight whenever they appear onscreen. It's a bleak yet beautiful film, and a highlight of the genre.