Why Marvel's Stan Lee Wasn't A Big Fan Of X-Men: The Animated Series

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

You can debate long and hard about how much of the late Stan Lee's legacy as the Marvel Comics' mastermind is deserved. However, he definitely became as much of a face for the Marvel brand as Spider-Man is. All his cameos in the Marvel movies helped cement that, but when not on the job at the movie shoots or red carpets, how did Lee feel about the adaptations?

The 2021 Stan Lee biography "True Believer" by Josephine Riesman quotes both Lee's former business manager Keya Morgan and his bodyguard Gaven Vanover with claims that Lee hated superhero movies. (Morgan was charged with elder abuse of Lee after Lee died in 2018, but was cleared in 2022.) But it was not just the movies, apparently.

Eric and Julia Lewald, the writer couple who story edited and wrote for "X-Men," noted in a 2016 interview that Stan Lee was not involved much with their show, or a fan of its direction. Now, Eric Lewald had kind words for Lee's creative spirit: "Stan loves to be involved creatively. He wants to be part of everything. He's an indefatigable, voracious guy."

However, the "X-Men" comics — written by Chris Claremont from 1975 to 1991 — had changed a lot since Lee and artist Jack Kirby's day in 1963. "I was told that [Lee] never liked the direction that the books had gone since 1975, and since we liked the newer books, he fought us on the tone and direction of the show," Lewald continued. Given how the show turned out, it appears Lee didn't fight hard enough.

The animated "X-Men" team line-up was similar to the Claremont cast (with a few exceptions), and the show adapted his biggest stories: "The Dark Phoenix Saga," "Days of Future Past," etc. If you weren't Stan Lee, this was all a no-brainer.

X-Men: The Animated Series adapted Chris Claremont, not Stan Lee

1975 was the year the X-Men rebooted, thanks to the "Giant-Size X-Men" #1 issue by Len Wein and Dave Cockrum. The original "X-Men" run had garnered low interest and was even semi-canceled in 1970; issues #67-93 were mere reprints of earlier stories. When Wein gave "X-Men" its new lease on life, it was with an almost entirely new cast of characters — most famously, Wolverine, who Wein had debuted in an earlier issue of "The Incredible Hulk." After "Giant-Size X-Men," Claremont took over as writer of the new "X-Men" series.

With a blank canvas to draw the stories and characters, Claremont made "X-Men" a book all his own. Claremont ultimately wrote "X-Men" for 16 years and almost 200 issues. He would've gone even longer (and had some wild plans for Wolverine), but he left abruptly in 1991 due to conflicts with Marvel Editor-in-Chief Bob Harras. Claremont staying on "X-Men" for so long wasn't just because he got comfortable; the book was acclaimed and a best-seller. Along with artist collaborators like Dave Cockrum, John Byrne, Paul Smith, Barry Windsor-Smith, and Marc Silvestri, Claremont turned "X-Men" around from a failure to Marvel Comics' juggernaut (pun intended).

I don't mean to speak ill of the dead, but if Lee really didn't like Claremont's "X-Men," then that tastes like sour grapes. I understand a creator's innate possessiveness, but the fact is, "X-Men" never flourished under Lee's pen. It wasn't even his most inspired concept, but merely him and Kirby trying to recapture the magic of "The Fantastic Four." The cover of "X-Men" #1 boasts it is a comic "in the sensational Fantastic Four" style, the X-Men wear uniform outfits like the FF, and the characters hit the same broad archetypes.

Stan Lee's original X-Men were a poor man's Fantastic Four

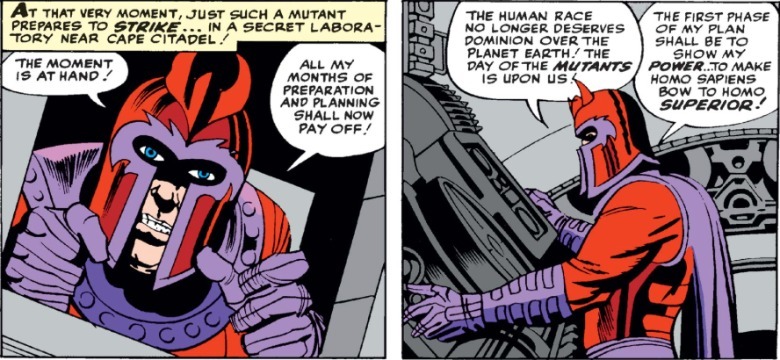

Professor X and Cyclops split the difference of Reed Richards as the team leader. Jean Grey is the Invisible Girl, the token (and often in distress) woman. Iceman is the Human Torch, the young jokester with elemental powers. The Beast, far from the latter Lord Tennyson-quoting Hank McCoy, is a blue-collar Brooklynite like the Thing. If the early X-Men are a wannabe FF, then Lee and Kirby's Magneto is a pale imitation of Doctor Doom. The tragic villain that Claremont made Magneto into is nowhere to be found. The Master of Magnetism wants world domination, not mutant safety.

Compare this Magneto to the animated one, who, from his debut, speaks instead of a "war for [mutant] survival." This is also where the myth that Lee based Xavier and Magneto on contemporary Black civil rights activists Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X falls apart. The characterizations just don't match: Lee's Professor X wants to hide mutants in the shadows, while Magneto is a wannabe tyrant. (Even in 2014, when asked about that comparison by Rolling Stone, Lee only claimed it was "unconscious.")

The one provocative image in the Lee/Kirby "X-Men" debut issue comes from the winged mutant Angel, the only one without a clear FF analogue. Due to his huge wings, Angel doesn't "pass" as his comrades do; he has to bind his wings under his clothes when he goes out. When he lets them loose, he says he "feels like himself again." Compare this to how transgender people bind or tuck certain body parts to feel like themselves. It's no surprise "X-Men" evolved into a queer allegory, but like the Claremont run and the 1990s cartoon, that just shows the mutants grew beyond what Stan Lee intended.