When Anime Is No Longer Exclusively Made In Japan, Is It Still Anime?

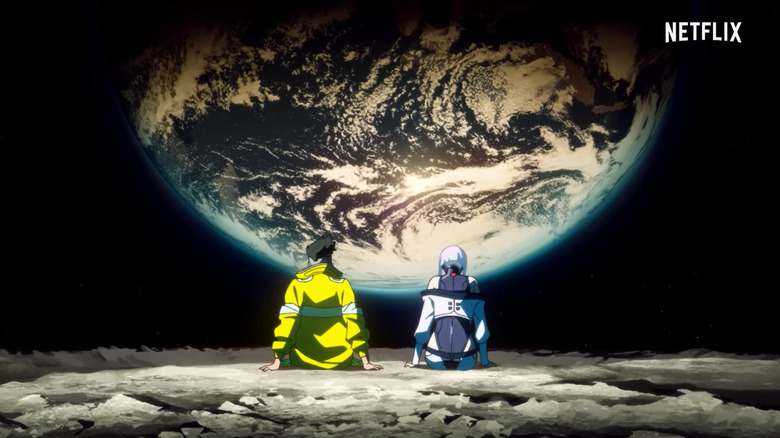

One of the more exciting animated projects set to debut on Netflix this year is "Cyberpunk: Edgerunners." Based on the highly promoted (and barely finished) video game, the series was pitched as a new production by the famous Studio Trigger. Bombastic action specialist Hiroyuki Imaishi is directing, wunderkind animator Yoh Yoshinari is contributing character designs, and much of the studio's creative brain trust is on board. Not to mention some first-time collaborators, like "Silent Hill" composer Akira Yamaoka. Imaishi is a wild card; he's best known today for his collaborations with the scriptwriter Kazuki Nakashima, but his early works like "Dead Leaves" forsake logic and characterization for rude cartooning. A cyberpunk anime produced by his team could be relentlessly kinetic and creative, embarrassingly puerile — or both!

But in the recently revealed "Edgerunners" credits, CD Project Red executive Rafal Jaki and comics writer Bartotsz Sztybor are listed above the Japanese scriptwriters, credited for "showrunner" and "screen story" respectively. The two of them appear in a video interview provided by Netflix for Geeked Week, with only a brief appearance by Yoshinari, Imaishi and Otsuka at the end. Listening to Jaki and Sztybor breathlessly praise Trigger's capabilities, I couldn't help but wonder: is "Edgerunners" a CD Projekt Red production, or a Trigger production? Trigger is best known in the industry for its original series. How much influence does the studio really have over a collaboration of this kind?

Fellowship of the ring

Anime is more popular today than it has ever been. The creative director of anime at Netflix, Kohei Obara, stated in a Variety article that more than half of their viewership watched anime on the platform in 2022. (The actual length of time spent watching was not specified.) In 2021, the anime streaming site Crunchyroll announced it had achieved 5 million streaming subscribers and 120 million registered users. Today the battle for licensing is fierce, with streaming services fighting for the rights to future hits like "Chainsaw Man." Even Disney Plus has entered the fray, picking up titles like Science Saru's "Tatami Time Machine Blues." International co-productions have also become increasingly common. While some of these projects have been original series, the majority have so far been adaptations of existing intellectual property.

One such example is the upcoming "The Lord of the Rings: War of the Rohirrim," an anime film set to build upon details from the earlier live-action trilogy. Kenji Kamiyama is to direct at Sola Entertainment, a studio whose output includes the ongoing "Ultraman" anime as well as "Ghost in the Shell: SAC_2045." The other announced names are all directly connected to the film trilogy, including writer Philippa Boyens, her daughter Phoebe Gittens and art director Alan Lee. No other Japanese creative staff is credited. It could be that Warner Bros made a choice in their marketing to highlight names that viewers from the United States might know. The alternative is that they see Kamiyama's crew as a means to an end, rather than giving them the respect they deserve as artists.

The Castlevania conundrum

While "The Lord of the Rings: War of the Rohirrim" is at least partially produced in Japan, many of Netflix's recent "anime" titles are not. One of the network's biggest successes is "Castlevania," an adaptation of the Japanese video game series scripted by influential (and disgraced) comics writer Warren Ellis. The staff of "Castlevania" are unabashed anime fans who loaded the show's signature fight scenes with impact frames and tricky effects animation. But the series was produced not in Japan but at Powerhouse Animation Studios, located in Austin, Texas. "Castlevania," along with "Blood of Zeus" and the recent "Masters of the Universe" animated series, have been lumped under the "anime" label despite lacking a connection to the industry. The service's other video game adaptations have been marketed similarly.

What does it matter if a product is labeled "anime" or not? As far as I can tell, it comes down to branding. Anime is popular, but "cartoons" in the United States are still associated with children's programming. Netflix labels their adult animated series "anime," anime fans check them out, everyone wins. My problem is less with the "anime" label and more the lack of respect afforded to the animation staff in this scenario. As a supposed mover and shaker in the entertainment staff, Netflix has the chance to give animation studios abroad a chance to come up with their own exciting ideas. Instead, Netflix often follows the hoary United States tradition of animation outsourcing. The showrunner and writer's room remains in-house, character designers and storyboarders send detailed instructions to countries like South Korea and the Philippines, and the underpaid animators who do much of the work never receive the recognition they deserve.

Trust and respect

It doesn't have to be this way. Over the past decade, there have been artists who chose to work directly with their outsourcing staff rather than taking their work for granted. The all-time greatest example may be "Avatar: The Last Airbender." According to a video by The Canipa Effect, producer Brian Konietzko took the time to personally meet with animation staff in South Korea before the series went into production. These animators were given unusual control over aspects like character design, effects drawings, and even animation timing. The great writing and storyboarding in "Avatar" was pushed to even greater heights by the efforts of its Korean animation staff, creating a modern classic that has still not yet been equaled within its niche. According to Callum May, the creator of The Canipa Effect, "it was the creative trust between the staff in the US and Korea that made it special."

One of the lead animation directors from "Avatar," Jae-Myung Yu, would go on to found Studio Mir. Studio Mir produced much of the ambitious "Avatar" successor "The Legend of Korra," and was then contracted by DreamWorks to produce the fan-favorite series "Voltron: Legendary Defender." Since then, they've produced countless "anime" productions for Netflix, including the film "The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf." It is clear from interviews that they take great pride in their work. In an interview with Polygon, "Nightmare of the Wolf" director Kwang-il Han says of studio founder Yu that "whichever project he was working on, he poured his heart into it and took ownership of it creatively, even if it wasn't an original work." Similarly, Han speaks of developing the character of Vesemir through adlibs in the boarding process via a ScreenRant interview.

Let it be Studio Mir style

The quality and breadth of their work have made Studio Mir one of the best-known South Korean animation studios internationally. Their print has become strong enough that when asked by Netflix producers whether to emulate Japanese or American style, their response was to follow the "Studio Mir" style. Yet the work of Studio Mir continues to be lumped by Netflix under their broader anime banner. At the same time, even as Studio Mir has proven itself again and again, they have not once been given the freedom by partners like Netflix or DreamWorks to create their own original series. Instead, they are harnessed to produce endless contract work for streaming libraries.

Rather than see these animators toiling on franchise movies and television series for the rest of their days, I would love to see what they might come up with on their own. For instance, director Kyohei Ishiguro was hired to direct "Bright: Samurai Soul," an animated prequel to a movie nobody I know actually liked. Why not instead fund a film more along the lines of "Love Bubbles Up Like Soda Pop," a film that plays more to his strengths yet was delayed from its 2020 release by COVID-19? Similarly, I'd love to see Studio Mir be given the opportunity to produce original work, or at least decide what property they would like to adapt rather than accept work for hire. Not to mention that Japan has many talented directors and animators, like the talented Rie Matsumoto, who nobody in the industry seems to know what to do with. Maybe when she isn't making incredible commercials for Pokemon, somebody could pay her and her team to finally make the movie they've been threatening for years?

Anime is a global medium

It's not that simple, of course. Up until now, I have been insisting in this article that there is a clear break between streaming services in the United States and the Japanese anime industry abroad. This was debatably true several years ago, but is no longer true anymore. As our friend Callum May has said, anime is a global medium. Streaming services like Netflix and Crunchyroll directly produce and fund series aimed at international audiences. Licensing fees paid by these services are often high enough to cover the cost of anime production itself. As of 2020, according to a report by the Association of Japanese Animations, the global anime market surpassed that of Japan for the first time in history. While anime is not quite as mainstream as films produced by Disney, the medium is now well on its way for better or worse.

Over the past few years, the boundary between Japan's anime industry and the rest of the world has become increasingly permeable. Background artists like Kevin Aymeric, animation directors like Vincent Chansard, and composers like Kevin Penkin have all found success in today's anime world. Bahi JD, who once drew web animations for release on YouTube and forums, now storyboards opening sequences and handled important action scenes in Trigger's firefighter epic "Promare." At the same time, artists from the anime industry have crossed over to projects in the United States. Masaaki Yuasa boarded an episode of Adventure Time, former Trigger animator Takafumi Hori contributed to the "Steven Universe" movie, and character designer Shigeto Koyama handled the concept for Baymax in "Big Hero 6."

The poisoned gift

A major sea change occurred in 2021 with the release of "Wonder Egg Priority," a series created by talented young animators seeking to deliver both delicate character acting and high-octane action at a level of quality closer to film than television. After an astounding opening run of episodes, the series quickly imploded and became unfeasible to make. It was only finished due to the efforts of foreign fans hired at the last minute, including university students Blou and FAR. Considering their relative lack of experience and the hellish conditions of the show's final stretch, their team went above and beyond. Blou and FAR have continued to rise with their friends at Studio Tonton, assisting on the production of popular anime like "Spy X Family."

But in an interview at Anime News Network, the two of them warn prospective animators to be careful before following their lead. According to Blou:

"Nowadays, production assistants are quite desperate and can offer anyone who can simply draw (in some cases, even that criteria wasn't fulfilled). You might be happy to receive an offer when you aren't ready, but the truth is that it's a poisoned gift. Take your first job only when you're (more than) ready!"

The greatest danger facing today's anime industry is overproduction. Not only is too much anime being made, but the high-profile action series that find great success abroad are themselves unsustainable. As animators drop out of the industry due to low pay and terrible treatment, producers turn to foreign animators with no training and experience but enough passion to be underpaid and overworked in turn. "Chainsaw Man," produced at the high-profile but infamously mercenary studio MAPPA, threatens to become the next battleground in this ongoing struggle between sustainable art and commercial strip-mining.

Overproduction is a global symptom

Just as streaming companies abroad have funded both anime and "anime" series for international release, producers from Japan's anime industry have begun exerting a heavier influence abroad. Today's booming anime market stands to make both the production committees that secure funding for anime productions, as well as the networks which secure those productions via licensing fees, very happy. The losers, unfortunately, are the artists. To meet the high rate of production, they must overwork themselves while cutting as many corners as possible. Adaptations are flattened. Original series, which require even more pre-production, become unfeasible. Today's anime bubble could very well pop within the next five years, a casualty of venture capitalists looking to make a quick buck from another passing fad.

Whether anime is made in Japan or elsewhere, the heroes and the villains are the same. Animators struggle to do their job successfully within short time frames and under low wages. The wealthy consolidate their power and sacrifice the long-term good of an art form for short-term profit. Meanwhile, the United States television industry faces a shortage of trained showrunners. In the special effects industry, tasks are farmed abroad to countries without worker protections in order to save on costs. If anime is a global medium, its existential threats are also global. But then, so are its solutions. At Disney Studios, animators demanded a "New Deal for Animation." The manga publisher Seven Seas recently forged a worker's union. I can't say what the future holds for the anime industry, but I'm sure that its employees have ideas. It falls upon us to remember that regardless of origin, the content that makes streaming services run is spawned from the blood and sweat of human beings.