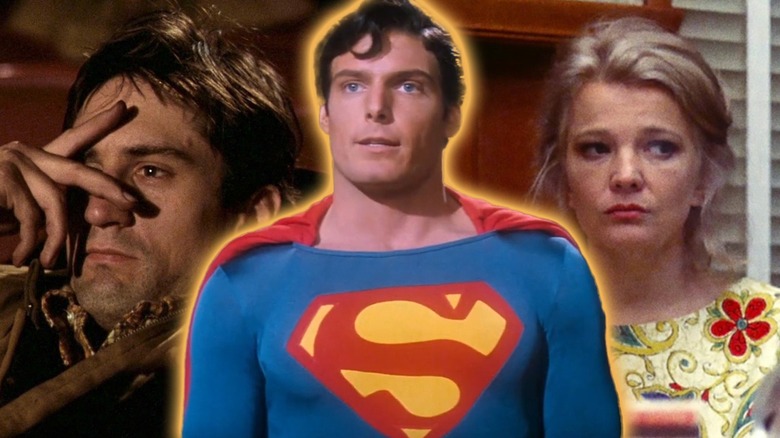

12 Great '70s Movies We Can't Believe Didn't Win An Oscar

The Oscars and its history of nominees and winners can often be taken as a useful snapshot of Hollywood in a given time period. While no one has really put stock in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as an arbiter of taste in about 50 years, lists of winners can give you a pretty good idea of what was popular, what was trendy, and what was acclaimed in, say, a particular decade.

This, of course, only makes it weirder to learn that certain beloved, iconic, and Academy-friendly movies have no Oscars to their name. In the '70s, the Academy's batting average was higher than usual, courtesy of its taste for aesthetic adventure brought on by New Hollywood. But there are still some enormous classics that got fully shut out despite checking all the boxes of Oscar-readiness — we're not talking "Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles" here, but films that should fall right in with what the Academy Awards were built to reward. Here are 12 great '70s movies that we can't believe didn't win any Oscars.

Taxi Driver

There's a contingent of critics and movie fans who would readily cite Martin Scorsese's "Taxi Driver" as the best American movie of the '70s. Even at the time, it was roundly acclaimed, a big box office hit, won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and collected Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Best Actor (Robert De Niro), Best Supporting Actress (Jodie Foster), and Best Original Score (Bernard Herrmann). And yet, somehow, the "Taxi Driver" team walked away completely empty-handed from the 1977 Academy Awards ceremony.

Of those four losses, Herrmann's posthumous defeat was maybe the most understandable, as he'd already won an Oscar back in 1941, and the 1977 winner, Jerry Goldsmith's subversive choral score for "The Omen," was indeed a phenomenal achievement. Meanwhile, in the acting department, "Taxi Driver" had the misfortune of going up against "Network," one of three films in history to win three acting Oscars — such that both De Niro and Foster were denied recognition for their legendary, decade-defining performances.

And then there was the whole debacle in which "Rocky" took home an excessive Best Picture prize in a wave of bicentennial patriotism. That just seems silly in hindsight when its competition was "Taxi Driver," even if the latter was inexplicably robbed of nominations for Scorsese's direction and Paul Schrader's script.

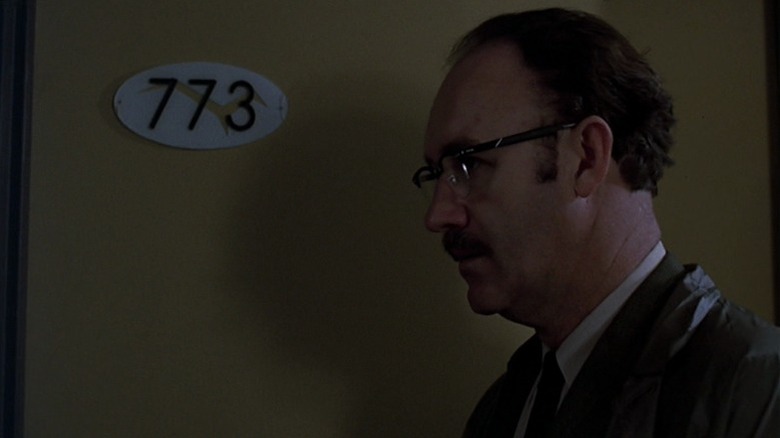

The Conversation

Considering that the other claimants to the title are "Apocalypse Now" and the first two "The Godfather" films, the fact that "The Conversation" might be Francis Ford Coppola's best film says a lot about its rarefied greatness. Coppola's Gene Hackman-starring 1974 paranoia thriller is a masterpiece of disorientation and unease that anticipated contemporary anxieties around omnipresent surveillance. Even so, it won zero Academy Awards.

Truth be told, the field at the 47th Oscars was a particularly crowded one. "The Conversation" was up against Coppola's own — and significantly more popular — "The Godfather Part II," which released the same year and won both Best Picture and Best Director. Similarly, in the Original Screenplay field, Coppola faced none other than Robert Towne for "Chinatown," widely held to be one of the best scripts in Hollywood history.

Hackman, meanwhile, lacked momentum following his then-fresh Best Actor win for "The French Connection," and he wasn't nominated for his phenomenal turn as surveillance expert Harry Caul — and even if he had been, he might've still lost to Art Carney in "Harry and Tonto," the same performance that also controversially led to snubs for Al Pacino and Jack Nicholson. The final of three nods for "The Conversation" was in Best Sound, which should have been a no-brainer, as it features perhaps the most carefully-crafted sound design in any Hollywood movie ever. But the statuette ultimately went to the disaster tentpole "Earthquake" in a classic Oscar instance of "most" prevailing over "best."

A Woman Under the Influence

John Cassavetes was a fearless maverick who changed the face of American cinema, but there were only two instances in which his sensibilities aligned with the mainstream enough to net Oscar attention. First, 1968's "Faces" earned him a nomination for Original Screenplay — ever the province of films too good to ignore but too cool for the main categories — and acting nods for Seymour Cassel and Lynn Carlin.

And then there was 1974's "A Woman Under the Influence," which became such an ubiquitous critical sensation that it saw Cassavetes graduate into the club of respected arthouse filmmakers who sneak into the Best Director field for non-Oscar-friendly work (a feat he shared that year with François Truffaut for "Day for Night"). Additionally, Gena Rowlands scored an inevitable Best Actress nomination for her work as neurodivergent housewife Mabel Longhetti, widely singled out even then as one of the greatest performances in movie history.

When push came to shove, however, Cassavetes' direction lost out to Francis Ford Coppola's helming of "The Godfather Part II," and Rowlands was bested by Ellen Burstyn in "Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore." And while those two were also fantastic achievements, the end result of "A Woman Under the Influence" counting zero Oscars feels wrong for a movie that galvanized '70s cinema so completely and notoriously. And the Academy didn't even nominate Peter Falk, whose work as Mabel's husband Nick is nearly as brilliant as Rowlands'.

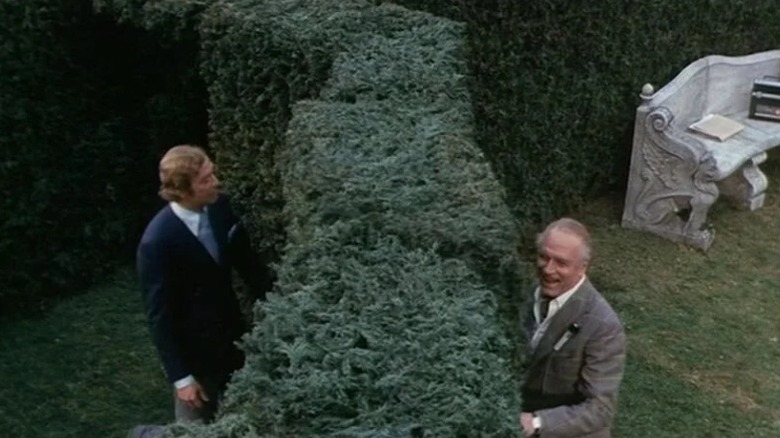

Sleuth

On paper, the 1972 crime thriller "Sleuth" had everything to be a huge Oscar player. There was Old Hollywood legend Joseph L. Mankiewicz making a long-awaited comeback in the director's chair. There was screenwriter Anthony Shaffer, adapting his own hit stage play, which had won the Tony for Best Play just a few years prior. In the cast, there was Sir Laurence Olivier, symbolically passing the torch to then-up-and-comer Michael Caine. There was the elegance and respectability of the concept: Just two actors, methodically unspooling the various twists of a sophisticated mystery in a single location. There was even the massive critical acclaim.

In the end, even with all that, "Sleuth" scored just four nominations — for Olivier, Caine, Mankiewicz's direction, and John Addison's score — and zero wins. 1972 may have been the single year in which a sturdy, crowd-pleasing, stylistically conservative adult drama was not automatically in a favorable position with the Academy: It was the year of "The Godfather" (which won Best Actor), "Cabaret" (which won Best Director), "Deliverance," and "Sounder," a quartet of envelope-pushers that marked the full swing of New Hollywood. Add in the Swedish epic "The Emigrants," also Oscar-friendly but boasting a little more arthouse cred as an international film, and you had a full set of five Best Picture nominees with no room for a plain old "regular" great movie like "Sleuth." Ultimately, however, "Sleuth" stood the test of time, even going on to inspire a subtle nod in "Knives Out."

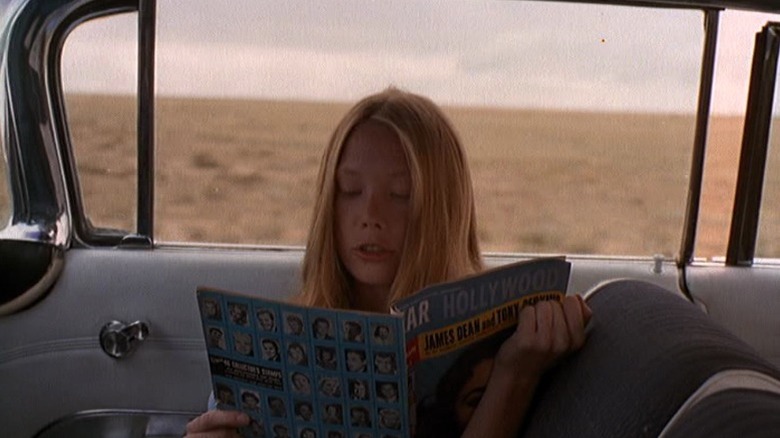

Badlands

When "Badlands" came out in 1973, not everybody noticed that it was a new American classic. Some immediately recognized the transformative genius in Terence Malick's stark, quietly political, philosophy-infused, radically non-moralistic account of senseless murder in the American heartland. But the movie was too out-there for either critical or commercial mainstream tastes. Box office-wise, "Badlands" was a big flop even for its relatively modest budget, and, save for a handful of passionate defenders, contemporaneous critical response was not ecstatic enough to push the film through the noise of its commercial untenability.

What this meant was that, when nominations for the 46th Oscars were announced in February 1974, "Badlands" was nowhere to be seen. No nods were given to Malick's direction, Jack Fisk's hauntingly evocative art direction, the unforgettable six-handed cinematography by Tak Fujimoto, Stevan Larner, and Brian Probyn, or George Tipton's acclaimed score. Even the performances of Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, both making their screen breakthroughs, weren't enough to get the Academy's attention.

The movie did succeed mightily in launching careers — Sheen's, Spacek's, and, naturally, their director's. After battling constant pressure behind the scenes of "Badlands," Malick had become an Academy household name by the time of his 1978 follow-up "Days of Heaven" (which won Best Cinematography) and went on to score Best Director nominations for 1998's "The Thin Red Line" and 2011's "The Tree of Life." He still has no Oscars to his own name, though, which is its own travesty.

Young Frankenstein

The question of which Mel Brooks film is the out-and-out funniest depends heavily on the answerer's sense of humor, with cultural consensus having historically favored "Blazing Saddles." But if we're talking Brooks' most polished, sharp, and well-made film on the whole, the answer just might be "Young Frankenstein." The 1974 omnibus parody of the various screen adaptations of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein" was by far Brooks' most successful outing as both parody and homage, with an unusually tight and disciplined script and a surprising amount of visual panache, even if its gags didn't necessarily reach the surreal, cartoon-esque heights of "Blazing Saddles."

Not for nothing, "Young Frankenstein" became the second Brooks film to score an Oscar nomination for screenwriting after 1969's similarly refined "The Producers." To boot, Gene Cantamessa and Richard Portman's technically complex sound mixing earned a nomination for Best Sound. But, in another example of 1974 being an embarrassment of riches, "Young Frankenstein" lost the former award to "The Godfather Part II" and the latter — less justifiably — to "Earthquake." The even greater absurdity, arguably, is that Peter Boyle's pitch-perfect performance as the Monster and Gerald Hirschfeld's painstaking '30s-recreating cinematography weren't even nominated. And "Blazing Saddles," in the running at the very same ceremony, didn't fare much better: Madeline Kahn lost what should have been her Supporting Actress award to Ingrid Bergman, who didn't deserve her Oscar that particular year.

Superman

1978's "Superman" technically did win a non-competitive special achievement Academy Award for its visual effects. At the time, the Academy had yet to get its act together and institute a proper, consistent Best Visual Effects category (something it wouldn't fully do until 1985, with "special achievement" statuettes still being handed out in place of a real VFX Oscar as recently as 1992). In competitive categories, meanwhile, the seismically influential blockbuster that found a way to make Christopher Reeve fly landed three nominations and zilch wins.

"Superman" was the most expensive film of all time up to that point — and, unlike many subsequent holders of that record, the budget absolutely showed on screen. Director Richard Donner made a point of whisking viewers off into once-unimaginable echelons of ecstatic fantasy, which is part of the reason why the movie is still so exciting to watch even today. The Academy responded by giving "Superman" nominations for Best Film Editing, Best Sound, and Best Original Score at the 51st ceremony.

But none translated to wins: John Williams' score lost to Giorgio Moroder's work on "Midnight Express," while Best Picture winner and overall sweeper "The Deer Hunter" won for editing and sound. Since special achievement awards are considered separate from awards of merit by the Academy, there are no men of gold in the Man of Steel's official tally; in fact, no "Superman" movie has won any competitive Oscars so far.

Harold and Maude

One of the great offbeat classics of the 1970s, Hal Ashby's "Harold and Maude" gave rise to pretty much the entire "quirky indie dramedy" subgenre of American film. (We might not have had Wes Anderson without it.) It also directly influenced a great deal of modern adult dramas in both film and television with its tonal fusion and groovy, song-guided montage editing. It's a canonical rom-com and a stunning, enlivening watch to this day, not only for its blend of sweetness and dark humor but for the fearlessness with which it depicts the blossoming of romance between 20-year-old Harold Chasen (Bud Cort) and 79-year-old Maude Chardin (Ruth Gordon).

The only thing "Harold and Maude" wasn't was a success upon release. Critics were not smitten with its eccentricity, and audiences largely rejected it. It wasn't until much later in its shelf life that the movie garnered the following that enabled its ascension to "American classic" status. As a result, "Harold and Maude" received very limited awards attention — Golden Globe nominations for Cort and Gordon in the Comedy or Musical categories (which they lost to Topol for "Fiddler on the Roof" and Twiggy for "The Boy Friend"), a Most Promising Newcomer BAFTA nod for Cort (which he lost to Joel Grey for "Cabaret"), and nothing at the Oscars. A shame, because Gordon, Cort, Colin Higgins' screenplay, and Cat Stevens' original songs would all have made perfectly worthy winners.

What's Up, Doc?

Straight-up comedies don't generally get the fairest of shakes at the Oscars, but there have been plenty of exceptions to the rule, including a number of Oscar-winning hits in the Old Hollywood era. Thus, you'd think a comedy expressly intended as an homage to that era's screwball classics would have a better chance of faring well with the Academy.

That nostalgia-friendly conceit wasn't the only thing 1972's "What's Up, Doc?" had going for it, either. Director Peter Bogdanovich was fresh out of the massive awards success of "The Last Picture Show," and the movie's cast included stars of such tidal pull as Barbra Streisand, Ryan O'Neal, and Madeline Kahn. To top it all off, reviews were great, box office numbers were off the charts, and one of the best action scenes ever gave the movie substantial technical cred.

Even with all those elements in place, however, "What's Up, Doc?" didn't impress Academy voters, who shut out the film entirely come nomination time. It was a strange, borderline inexplicable fate for one of the most beloved and successful studio comedies of the '70s, especially seeing as the script by Buck Henry, David Newman, and Robert Benton actually won the Writers' Guild of America Award for Best Comedy Written Directly for the Screen.

Sorcerer

William Friedkin's "Sorcerer" is now considered one of the very best films in the oeuvre of the "The Exorcist" auteur and a towering influence on all subsequent action thriller cinema. That alone would suggest a movie that ought to have had at least a little Oscar glory. And then there's the fact that Friedkin was, well, the director of "The Exorcist" — a gigantic hit, released just four years prior to "Sorcerer," that was improbably able to revert the Oscars' anti-horror bias and win two statuettes from a whopping 10 nominations.

Working against "Sorcerer," ultimately, was its failure to become a similar hit. A perfect storm of problems resulted in a budget that the movie's modest global box office intake didn't come anywhere close to recouping, and even some of the most tense and handsomely-directed set pieces ever committed to film weren't enough to bring it contemporaneous acclaim.

A single Academy Award nomination was achieved: A well-deserved Best Sound nod for Robert Knudson, Robert J. Glass, Richard Tyler, and Jean-Louis Ducarme. But "Sorcerer" lost that one to the same film that had hampered its box office potential: "Star Wars." It was the year of "Star Wars," really; even as it lost Best Picture, the George Lucas film rode its world-changing box office to nominations for directing, film editing, art direction, music, screenwriting (screenwriting!), and more. "Sorcerer" deserved all of those nods too, as well as one for cinematography, but alas.

3 Women

Robert Altman's filmmaking career had almost too many high points across too many genres and cinematic eras to keep up with. In retrospect, however, 1977's "3 Women" emerges as one of his unambiguous masterpieces. It's a brazen, hallucinatory study in formal and psychological fluidity, in which an expert of pop cinema married his crowd-pleasing chops to an unprecedented level of instinctual, unbridled artistry. Its box office take was never going to be on the level of "M*A*S*H" or "Nashville," but even so, the amount of effusive (albeit not unanimous) critical support it received should have been enough to put it on the Academy's radar.

If not the critical passion, then, at least its stars: "3 Women" features '70s icons Shelley Duvall and Sissy Spacek in some of the best, most committed work of their careers, along with the lesser-known but equally brilliant Janice Rule in an unforgettable supporting turn. Playing in competition at Cannes, where Altman contended for the Palme d'Or and Duvall took home the Best Actress prize, should've also helped to prop up the movie. (The same goes for its accolades from the New York, Los Angeles, and National Society of Film Critics.) At the Oscars, however, Altman, Duvall, Spacek, and Rule were all denied nominations, and "3 Women" was 100% shut out. Pretty embarrassing for the Academy, frankly.

Blue Collar

One of the best movies set in Michigan, "Blue Collar" is not always cited alongside the likes of "Taxi Driver," "Dog Day Afternoon," and "The Conversation" among the great American urban dramas that took the pulse of the 1970s, even though it very much should be — and that comparative lack of popularity probably stems in part from the fact that it went completely ignored by the Oscars. Even accounting for how comparatively friendly the Academy was to radical, of-the-moment cinema in the '70s, its overlooking of "Blue Collar" stands as a testament to just how constitutionally out of lockstep the Oscars are with the currents of cinema at the end of the day.

There's no good justification, after all, for giving the cold shoulder to this gobsmacking 1978 film, in which Paul Schrader alchemized his gifts as a screenwriter and his nascent chops as a director into the thundering final rondo of New Hollywood. "Blue Collar," with its uneasy, explosive mix of jittery comedy and anti-capitalist grand tragedy, was a critical and box office success that impressed and influenced innumerable filmmakers; enormous praise went to Schrader's writing, Tom Rolf's editing, Jack Nitzsche's score, and central trio of Richard Pryor, Yaphet Kotto, and Harvey Keitel. But the movie was ultimately too raw, strange, angry, and close to the bone — and, let's face it, probably too Black — to gain favor with Oscar voters at large.