10 Forgotten Oscar-Winning Movies Every Cinephile Needs To Watch

Though Louis B. Mayer created the Academy Awards as a union-busting enterprise and a bid for further studio control, they're now considered the highest honors in Hollywood. Studios put millions into Oscars campaigns for their films and stars, and Oscars commentary has become an industry in and of itself. In the Internet age, the Academy Awards now generate iconic viral moments like the memorable "La La Land" and "Moonlight" mix-up in 2017.

Even as we recognize their insignificance, it's difficult not to get invested in the outcome of the Oscars. However, as Oscar voters are fallible people, they don't always get it right. Remember when "Green Book" inexplicably won Best Picture in 2017, mirroring the "Driving Miss Daisy" controversy in 1990? The history of the Academy Awards is filled with instances of voters having very bad taste and having very good taste — though, of course, taste is subjective.

Indeed, some Oscar winners are best left gathering dust. But in other cases, awardees that we've mostly forgotten about deserve reconsideration. After all, the Oscars began nearly 100 years ago, and while there are certainly plenty of mediocre films that took home little gold men, it's worth sifting through the list to find the hidden gems. What follows is a sampling of those gems, films that received critical acclaim at the time of their release but haven't maintained the popularity they deserve.

Here are some forgotten Oscar-winning movies that are worth watching for any cinephile.

Wings

Though it's certainly well-known to film historians, not many folks have seen the first film to win Best Picture. That film was 1927's "Wings," starring Clara Bow, Paramount's biggest star. The story follows two men, David (Richard Arlen) and Jack (Charles "Buddy" Rogers), who enlist in the military as combat pilots. Mary (Bow), a girl from their hometown, becomes entangled with the two men, as she's in love with David but pursued by Jack.

Though it's been forgotten by many outside the film industry, "Wings" was a very influential film, both in its era and today. Much of the film's acclaim is tied to its aerial sequences, which were unprecedented in their realism, and in many ways they laid the groundwork for modern-day action cinematography. Director William A. Wellman attached cameras to the stunt planes to capture their movements, and the crew used handheld cameras during battle sequences. It's hard to imagine Tom Cruise's death-defying "Mission: Impossible" plane stunts without the innovation of "Wings."

If you're a particularly scholarly cinephile, you might have seen one short clip from the film: the famous dolly shot scene. In it, the camera moves through a cafe, sliding between pairs of patrons until it reaches our protagonists' table. The clip is just as magical today, and Rian Johnson even included an homage to the scene in "Star Wars: The Last Jedi."

If that's not enough innovation for you, get this: "Wings" also features a kiss between its two male leads, which some call the first gay kiss in Hollywood history. If you look closely, you'll notice that one of the pairs in the dolly shot appears to be a lesbian couple. How's that for a first Best Picture?

The Awful Truth

One of the greatest and most prolific directors of his time, Leo McCarey isn't as well-known today as some of his contemporaries, such as Billy Wilder and John Ford. With over 200 films to his name, McCarey only won four Oscars, three of which were for his 1944 film "Going My Way." He also won Best Director at the 1938 Oscars for "The Awful Truth," a far superior film.

The film stars two Hollywood greats, Cary Grant and the underrated Irene Dunne. They play Jerry and Lucy, a married couple who have just filed for divorce in a fit of jealousy. They try to go their separate ways, but find they aren't able to. Lucy finds herself wooed by Dan (Ralph Bellamy), a provincial Oklahoma oilman. Meanwhile, Jerry begins dating a heiress, Barbara Vance (Molly Lamont), who's way out of his league. Can the pair really move on? They have 30 days until their divorce is finalized, and neither Jerry nor Lucy can watch the other move on without a little sabotage.

Because "The Awful Truth" was made during the Hays Code era, there couldn't be any explicit references to sex. But since Jerry and Lucy were married, we can comfortably assume they have had "moral" sex before. This allows McCarey to put the characters in cheeky, salacious situations without having to tiptoe around the sex issues. The result is one of the best screwball comedies of all time, with Grant at the height of his wonderfully clownish powers and Dunne delivering a masterfully precise comedic performance.

Rebecca

Though he's no doubt one of the most popular directors of all time, few cinephiles have seen all of Alfred Hitchcock's 50-plus movies. While some of his lesser-known films aren't worth your time, "Rebecca" certainly is. Hitchcock's first American picture, the film was adapted from the novel of the same name by Daphne du Maurier. A blushing Joan Fontaine plays an unnamed woman who marries wealthy, standoffish widower Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier), and she is known thusforth as the second Mrs. de Winter.

When Maxim takes his new bride back to Manderley, his creepy old mansion, she struggles to adapt to her new lifestyle. The housekeeper, the cold, severe Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), takes an immediate dislike to the second Mrs. de Winter, acting downright hostile towards her new employer. Other times, Mrs. Danvers becomes wistful, reminiscing about Rebecca –- the first Mrs. de Winter -– and how perfect she was. Things become more frightening and mysterious around the mansion until the film's striking conclusion.

Though there aren't any explicit supernatural elements nor much violence, "Rebecca" nonetheless qualifies as a ghost story and certainly as a psychological thriller. The title character never appears in the film, but her presence casts a long shadow, and she becomes a ghost through Mrs. Danvers' devotion and Maxim's avoidance. An essential entry in the queer film canon, the film presents Mrs. Danvers as a jealous lesbian villain whose unnatural obsession threatens to destroy everything. Though the history of queer villains is troubling, "Rebecca" remains a fascinating, complex piece of art, and its Best Picture win was well-deserved.

How Green Was My Valley

A simplistic way to tell the story of the 1942 Oscars is that it was the year Orson Welles' "Citizen Kane" lost the Best Picture award. Described by many as the greatest film ever made, in retrospect, its loss seems prosperous. It seems even stranger that "Citizen Kane" lost to a film few have heard of, but John Ford's "How Green Was My Valley" deserves a bit more credit than that.

One of the great American auteurs, Ford is most associated with Westerns (including one that inspired "Citizen Kane"), though his over 140 films span across genres. "How Green Was My Valley" represents Ford at his most sentimental and uncomplicated, though the film's tranquil beauty belies the momentous effort of its production. The picture follows the Morgans, a large family of miners in Wales. We watch the story unfold through the eyes of Hew (Roddy McDowall), the youngest child in the family. Set in the late Victorian Era, the movie illustrates how the decline of mining affects the family's way of life.

A highly nostalgic film, "How Green Was My Valley" depicts the past as a gentler, simpler time. Ford achieves this tone through his stunning visuals, using wide shots, vivid images of mountain landscapes, and breathtaking compositions of humble mining life. The dialogue is poetic (sometimes literally), and it features numerous songs, making the film both a feast for the eyes and ears. Though the story is purposefully un-dramatic, lacking the action of many of Ford's other films, its indisputable beauty gives you a sense of why so many Oscar voters were wowed by it.

Klute

Jane Fonda has had an incredible career, skyrocketing to fame as a young woman in the 1960s and 1970s and maintaining that fame well into her 80s. Now better-known for her activism than her acting, Fonda's prolific work on screen shouldn't be overlooked. Nominated for seven Oscars over her decades-long career, Fonda won her first statue in 1972 for the film "Klute." Fonda plays Bree, a high-priced sex worker with many wealthy and influential associates. Detective John Klute (Donald Sutherland) ropes Bree into a case involving one of her clients, and she's faced with more danger than she bargained for.

The members of the Academy were right to bestow the highest acting honor on Fonda, who gives an electrifying performance in the film. In his review of the film, Roger Ebert wrote that "[Fonda] has a sort of nervous intensity that keeps her so firmly locked into a film character that the character actually seems distracted by things that come up in the movie." Ebert rightfully wonders why the film wasn't named after Fonda's character rather than Sutherland's.

Of course, Fonda isn't the only impressive element of the film, which was directed by New American filmmaker Alan J. Pakula. "Klute" represents the first entry in his loosely defined "paranoia trilogy," which also includes "The Parallax View" and "All The President's Men." Like those other films, "Klute" builds an atmosphere of suspicion – generated by surveillance and conspiracies – common among some of the most acclaimed films of the era.

Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore

It wouldn't make sense to call Martin Scorsese an underrated director, but he does have a few films that deserve more love. Take, for example, his 1974 picture "Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore," for which star Ellen Burstyn won her first and only Oscar. Burstyn plays the title character, a widow traveling across the southwest trying to start a new life with her son.

Along the way, she meets several interesting folks, including the volatile Ben (Harvey Keitel) and the kinder David (Kris Kristofferson), a divorced farmer. At the diner where she works, she meets the colorful Flo (Diane Ladd, also nominated for an Oscar for the film), who offers her sage wisdom about womanhood, and the quiet Vera (Valerie Curtin), Flo's opposite. For her part, Alice has always dreamed of becoming a singer, but things never seem to go her way.

"Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore" cares more about character than plot, and its characters are so well-drawn that the plot doesn't seem to matter. Most scenes are self-contained nuggets of conversation and ordinary interactions between people, but woven together, they tell the story of Alice's life, both where she's been and where she's headed. Far from the action-packed escapades found in his other films, here, Scorsese shows off his ability to capture the everyday idiosyncrasies of folks whose trials and tribulations never reach the heights of melodrama.

Ordinary People

Hollywood star Robert Redford is more than just a pretty face on screen — he's also an accomplished director. Redford has helmed nine feature films during his storied career, and his directorial debut won him his first and only Oscar for Best Director. Based on the Judith Guest novel of the same name, "Ordinary People" digs deeper than most family dramas. We meet the Jarretts, a wealthy family in Illinois struggling to cope with the loss of their teenage son.

The surviving son, Conrad (Timothy Hutton), feels responsible for his brother's death and is recovering from a suicide attempt. He works with a therapist, Dr. Berger (Judd Hirsch), to explore his feelings. Conrad's mother, Beth (Mary Tyler Moore in an all-time great performance), refuses to accept the loss and pretends as if everything's normal, seemingly punishing Conrad for his survival. Meanwhile, Calvin (Donald Sutherland) tries to make peace between his wife and son while working through his own grief.

Due to their wealth and privilege, the Jerretts don't exactly represent the average American family, but "Ordinary People" tells us that privilege doesn't do much to soften the blow of death. Grief, after all, is the great equalizer. The family's explosive feelings can't be contained within the nicely organized boxes of upper-class American life – everything falls apart both because of and despite their striving for perfection. Redford achieves something extraordinary here — imbuing every frame with truth and humanity, excavating the turmoil of ordinary people without sensationalizing their pain.

Dangerous Liaisons

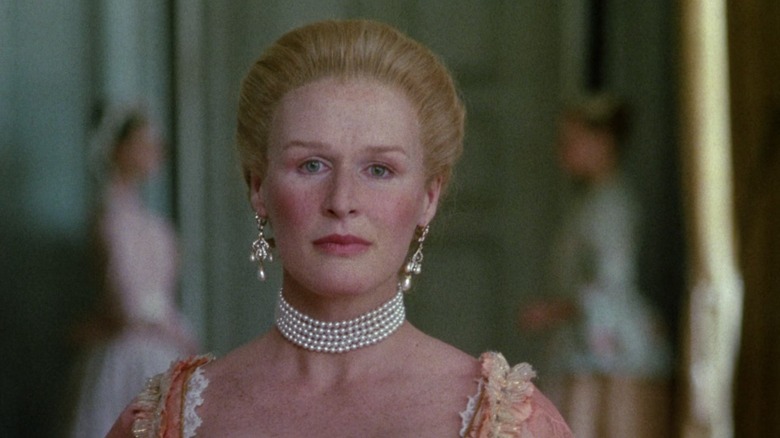

Though far from a household name in America, British director Stephen Frears has helmed three movies nominated for Best Picture. None of his films won the biggest award of the night, but his 1988 movie "Dangerous Liaisons" won for Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Art Direction, and Best Costume Design. A period piece about a gaggle of shady royals with nothing better to do than meddle, the film is a total hoot.

It's difficult to explain, but the plot of "Dangerous Liaisons" goes something like this: Glenn Close's character convinces her ex, played by John Malkovich, to ruin her other ex's life by seducing his virginal new beau in exchange for one more night with her. Meanwhile, Malkovich's lothario character plots to deflower a devout religious member of the royal court. Michelle Pfeiffer and Uma Thurman play the victims of the devious duo's dastardly schemes.

Sort of like an 18th-century "Cruel Intentions," the film delights in the conniving machinations of its characters, letting them loose within the grandiose halls of the French royal court. While Malkovich's character is too sleazy to truly root for, it's hard not to cheer for Close's demented aristocrat, particularly because Close gives a gleefully vicious performance. Did we mention that angel-faced Keanu Reeves also makes an appearance as a sensitive music teacher who weeps at the opera? Don't sleep on this hidden gem.

Affliction

Many of Paul Schrader's films, both those he's written and directed, follow violent men fighting to overcome a sense of inadequacy. Nowhere is this more clear than in "Affliction," one of Schrader's best films and also one of his most underrated. Based on a novel by Russell Banks, the film stars Nick Nolte as Wade Whitehouse, a cop in New Hampshire. Raised by an abusive, alcoholic father, Glen (James Coburn), and despised by his ex-wife and daughter, Wade sleepwalks through his life.

He's jolted awake by a case involving a potential murder, and the investigation consumes him. Only, this is not a murder mystery. It's a character study about a man who has lost his mind, with the murder serving only as a red herring. Indeed, the real plot of the film revolves around the relationship between father and son, its toxicity, and Wade's inability to recover from Glen's abuse. We hear the tale as told by Wade's quieter brother, Rolfe (Willem Dafoe), giving the story a sense of eerie distance and imminent doom.

"Affliction" is as bleak as can be, and it succeeds primarily because of two amazing lead performances. Nolte plays against his persona as both an action hero and a man of romance, crawling into the body of a truly broken man. Coburn, who won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for the role, gives the performance of a lifetime. While Schrader admits to having cast Coburn because of his imposing size, the role finally gave Coburn a chance to prove he's more than just a tough guy. When Schrader told Coburn how he wanted him to play the role, he responded (via RogerEbert.com), "Oh, you mean you want me to really act? I can do that. I haven't often been asked to, but I can."

Traffic

Steven Soderbergh's 2000 film "Traffic," for which he won Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay, zooms in on a fruitless war with no end. Centering on drug trafficking in North America, the movie tracks several people involved in the drug trade, both north and south of the border. Benicio del Toro and Jacob Vargas play Mexican police officers with a corrupt boss. Michael Douglas plays an Ohio judge fighting the war on drugs while his daughter falls into addiction. Steven Bauer plays a powerful drug lord, and Catherine Zeta-Jones his blissfully ignorant wife. Don Cheadle and Luis Guzmán play undercover DEA agents trying to solve a never-ending case.

Soderbergh uses his signature style to great effect here, tinting each portion of the film with a unique color to differentiate them. Many of the colorful plotlines never intersect, and the evolving chaos of these narratives gives a sense of how far-reaching the drug trade is. Everyone is affected, but at the same time, no one is effective, save the drug lords making millions off the backs of addicts and traffickers.

Like Robert Altman's "Nashville," the film disrupts the standards of cinematic time and movement, as Soderbergh's handheld cameras give the action a sense of immediacy and realism. To the director's credit, the film is never preachy or prescriptive. Rather, the movie's chaos illustrates the inability of one politician, agency, or policy — save, perhaps, decriminalization — to change the system.