The John Ford Western That Inspired Citizen Kane

It is nighttime on the periphery of a sprawling estate; sinister music accompanies the camera as it scrolls up over many yards of fence, chain link giving way to curlicues of wrought iron, punctuated with ominous cautions to prying eyes: "Warning Keep Out" and "Trespassers Will Be Shot," before arriving at a paper note reading "Free Kittens, Inquire Within."

We are, of course, talking about the opening to "Rosebud," the episode-length parody of "Citizen Kane" in "The Simpsons." Orson Welles' influential and much-referenced masterpiece needs little introduction, one of those films where most people know the iconography, even if they haven't seen the movie itself.

The famous opening scene that "The Simpsons" riffs on so wonderfully is one of the greatest ever committed to film, introducing us to Xanadu, the daunting edifice that Charles Foster Kane calls home. When I took film studies at university, we spent a lot of time on "Kane," picking through its treasure trove of cinematic wonders. I came to regard Xanadu as a metaphor for the film — a humbling monument to Welles' immense talent which he never quite managed to better or escape.

"Citizen Kane" inspires awe and casts a Xanadu-like shadow over cinema, even if it is a difficult film to actually love. Personally, I wholeheartedly adore "Casablanca," while I can only admit to cooing with admiration over "Kane." That is reflected in public "Best Films of All Time" lists; on IMDb's Top 250, it lags far behind "The Shawshank Redemption" and "Forrest Gump," while critics' polls usually place it somewhere near the top.

For the longest time, it occupied the top spot on Sight and Sound's highfalutin Top 250, before it was knocked off by Hitchcock's "Vertigo." That's something that would no doubt send Welles into a fit if he was alive to see it; the director famously hated Hitchcock's work, claiming he made films that were "all lit like television shows" (via Open Culture). Welles developed a reputation for hostility towards his peers during his career, pulling no punches with his withering criticism on everyone from Michelangelo Antonioni (whose films were "perfect backgrounds for fashion models") to John Landis ("Kill him.")

Yet for all Welles' innovation, virtuosity, and innate talent, he himself was heavily influenced by an earlier film as he prepared to make his 1941 masterpiece.

So What Happens in Citizen Kane Again?

The story opens with an old man on his deathbed. He whispers "Rosebud," a snowglobe slips from his grasp and shatters on the floor, and his nurse enters. He is dead. A strident newsreel obituary reveals that the deceased is Charles Foster Kane, the immensely wealthy and influential newspaper magnate and industrialist, who went from humble beginnings at a failing New York tabloid to building a vast media empire. And that was just for starters.

As the story of Kane's last word emerges, a reporter is sent to unravel the mystery of who, or what, Rosebud was. He conducts interviews with many of Kane's former friends, wives, associates, and rivals, uncovering many aspects of the man's life, from his adoption as a child by a wealthy banker named Thatcher to his unhappy, controlling marriage to a talentless opera singer.

The true meaning of Rosebud remains an enigma to the reporter, who gives up on his quest. We return to Xanadu, where Kane's staff are boxing up or destroying his vast collection of belongings. One of the items thrown on the fire is an old sled, which we saw Kane riding as a child just before Thatcher took him away. As the toy is consumed by flames, we see one word painted on it: "Rosebud."

"Citizen Kane" is revered for the astonishing array of filmmaking on display; Welles regarded Hollywood as "the biggest electric train set a boy ever had" (via The Atlantic). When it came to making his audacious directorial debut, he reveled in laying out every inch of track he could lay his hands on, taking a crash course in cinema and using every technique that caught his eye. In that sense, he was a little like the Tarantino of his day, pilfering things from earlier movies and mashing them together in a way that felt wholly unique.

There is the non-linear narrative that explores the mystery of Kane's final word from multiple perspectives, and the deep focus photography that encourages us to search for clues in every inch of the frame. There are the brilliant uses of montage, noirish lighting borrowed from German Expressionism, and technical sleight of hand, as in the bravura moment where the camera seemingly swoops through a neon sign and a pane of rain-lashed glass. My personal favorite is the masterful use of dissolve in the opening scene as we traverse the ghostly Xanadu estate with the light of Kane's bedroom window always remaining in the same place, even when reflected in an abandoned boating lake.

Few directors ever get close to this level of cinematic sophistication in their entire careers, and Welles managed it at the ripe old age of 25.

How Did Orson Welles Get to Make Citizen Kane?

The circumstances leading to Welles making "Citizen Kane" are almost as remarkable as the film itself. He first won plaudits on Broadway for his daring all African-American adaptation of "Macbeth," setting the Bard's famous tragedy in the Caribbean. He was just 20 years old. He established the Mercury Theater where he first teamed up with actor Joseph Cotten, who would play an important role in many of his feature films, including "Kane." They would also star together in Carol Reed's noir masterpiece, "The Third Man."

He then took his repertory company to the airwaves where he staged one of his biggest stunts, the infamous adaptation of "The War of the Worlds," carefully calculated to trick listeners into thinking there was a real Martian invasion. Some fell for it and got scared, although reports of mass panic were overblown and subsequently became part of the Welles legend as a trickster and showman.

That notoriety took Welles to Hollywood where he was given unprecedented artistic freedom over "Citizen Kane," which angered William Randolph Hearst, the powerful newspaper magnate whose life story it was loosely based on. After conquering the stage and radio, Welles wasn't about to play it safe when RKO gave him a substantial budget and final cut on his first motion picture. Giving many of his Mercury Theater troupe their film debuts, he also brought on board screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, who had a personal beef with Hearst. With his wunderkind reputation for fearlessness and arrogance, Welles only went on to revolutionize modern American cinema and make one of the greatest films of all time.

What Was the John Ford Film That Influenced Welles?

According to his biographer, actor Simon Callow, Welles watched John Ford's "Stagecoach" up to 40 times before making "Kane." (via BBC):

"After dinner every night for about a month, I'd run Stagecoach, often with some different technician or department head from the studio, and ask questions. 'How was this done?' 'Why was this done?' It was like going to school."

Roger Ebert talks about this in his "Great Movies" review of "Stagecoach," perhaps one of his most elegant and succinct arguments for the greatness of any one film in the series. It's almost as if he is influenced in his writing by the stylish economy of the film itself (via Roger Ebert):

"The two films are hardly similar. What did Welles learn from it? Perhaps most of all a lean editing style. Ford made certain through casting and dialog that the purpose of each scene was made clear, and then he lingered exactly long enough to make the point. Nothing feels superfluous. When he deliberately slows the flow ... we understand it as the calm before a storm."

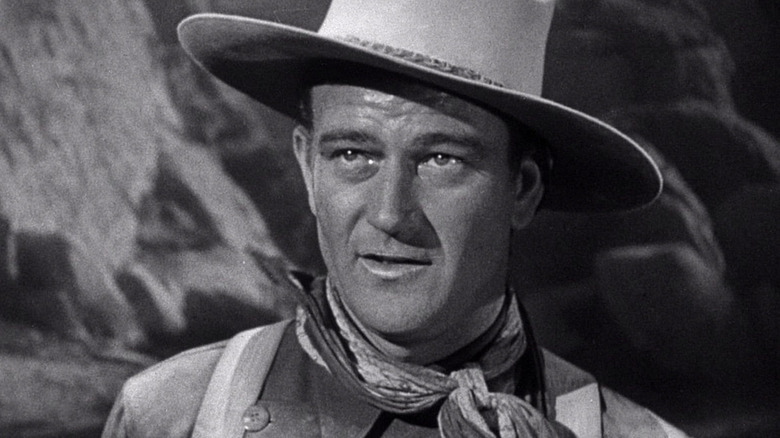

"Stagecoach" is a movie that I only caught up with recently. I knew it was regarded as one of the greats, but I was never a fan of cowboys-and-Indians style westerns. As a lefty, I was also resistant to it thanks to the presence of John Wayne, with his reputation as an ultra-conservative bigot and commie-basher. Neither of those things should deter anyone, especially those with an interest in the history of cinema, from seeing it. It's a cracking movie. Sure, the Native Americans as depicted here may as well be a horde of zombies for all they are humanized, but Ford's direction is so slick and authoritative. While many films of its age feel a bit old and stagey, "Stagecoach" really rattles along, even though much of the running time is spent establishing its set of flawed-but-likable characters. By the time the Indians finally descend on the stagecoach in the thrilling final chase scene (including one of the most dangerous stunts you'll ever see), we're fully invested in these people and there are real stakes.

As for Wayne, I finally got why he was such a huge star. He had played in dozens of previous movies but this was his big breakthrough role, and he's magnificent. There is a simple, mythic quality to his heroism, and he also has some surprisingly tender moments with the film's now well-worn trope of the hooker-with-the-heart-of-gold. Despite my preconceptions based on the man's politics that are totally unsavory to me, I couldn't help rooting for the guy.

The Aftermath of Citizen Kane

For all its massive influence over cinema, "Citizen Kane" was not a success when it was first released. Hearst waged war on the film, making sure his publications didn't run ads for it and turning Hollywood bigwigs like Louis B. Mayer against Welles (via History.com). As a result, it was a box office failure, despite favorable notices from many contemporary critics. Welles was booed at the Oscars, where "Kane" lost out on the Outstanding Motion Picture award to John Ford's "How Green Was My Valley,"' somewhat ironic given the veteran director's influence on Welles and his film.

In the fallout, Welles ended up becoming a contract director for RKO and losing creative control over his subsequent pictures, most notably "The Magnificent Ambersons," which was re-cut despite his protests. It was only in later years when "Kane" was re-released that it received re-evaluation and began its ascent to one of the most revered films ever made.

Ford, who had already helmed dozens of pictures since the early days of cinema before directing "Stagecoach," went on to make many more, earning his reputation as one of the great American filmmakers. During his career he directed over 140 movies, many in the western genre, collaborating with Wayne for some of their best films including "She Wore a Yellow Ribbon" and "The Searchers." While nowadays he is most well-known for his work with the actor, he also made many other classics including "The Grapes of Wrath" with Henry Fonda and "My Darling Clementine" with James Stewart.

While on the face of it "Stagecoach" and "Citizen Kane" may not have a huge amount in common, the earlier film's influence on Welles is where these two landmark moments of American cinema intersect. If you have any interest in cinema and you haven't seen one or both of these movies, I recommend you get on it straight away!