Transformers Once Paid Tribute To One Of Batman's Most Legendary Moments

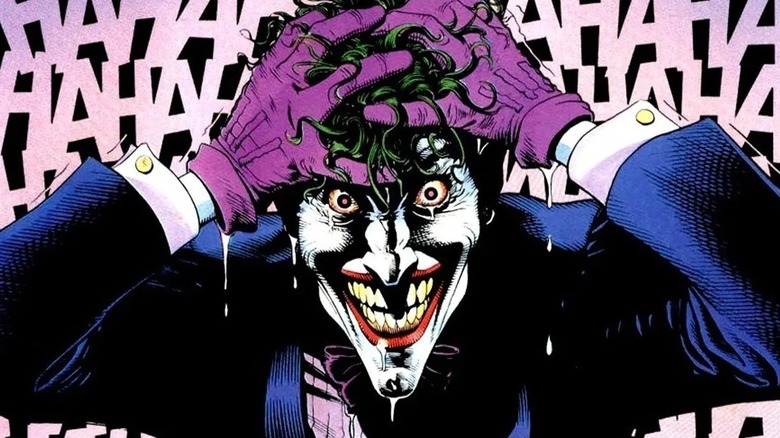

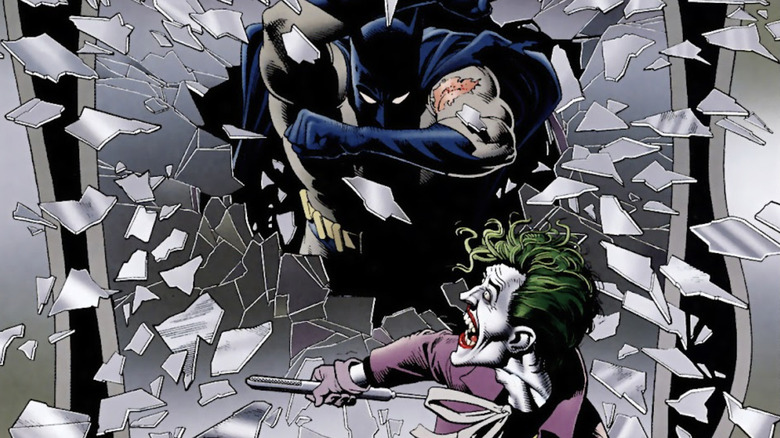

Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's 1988 graphic novel "The Killing Joke" is one of the most famous Batman stories. It's also undergone a more adversarial reevaluation in the 21st century due to its exploitative depiction of violence against women; the Joker shooting and disabling Barbara Gordon is a textbook case of a woman in a refrigerator.

Despite the ickiness, I still think it's a damn good comic. Bolland's artwork is gorgeous and the book interrogates Batman and the Joker's shared dynamic with depth every Batman writer since has been chasing.

In "The Killing Joke," the Joker abducts Commissioner Gordon and tries to push him to his psychological breaking point. As the Joker remembers it, he was once a regular man who had a really bad day that convinced him to laugh at how awful the world is. But his hypothesis is wrong; Gordon doesn't crack and Batman suggests the problem with the Joker always lay in his own heart. Batman offers the truly defeated Joker a chance at redemption, but the latter declines: "It's too late for that."

In "Transformers" issue #187 (published in October 1988, less than a year after "The Killing Joke"), writer Simon Furman and artist Lee Sullivan homaged this ending. Check out the pages side by side in a recent tweet from Mr. Furman:

That time we 'homaged' Batman: The Killing Joke in #Transformers (UK #187), art by Lee Sullivan. pic.twitter.com/9Tk7Rci68D

— Simon Furman (@SimonFurman3) January 30, 2024

I'm not sure Moore would take the homage as a compliment; he's antipathetic towards adaptations of his work and "The Killing Joke" itself. As an anarchist with an (understandable) distaste for the corporate comics industry, he especially dislikes the Marvel/DC superhero duopoly, Batman included. I'd bet that he'd also be disinterested in "Transformers," a franchise that exists first and foremost to advertise action figures.

Still, the homage shows that Furman and Sullivan at least understood "The Killing Joke" — which not all its imitators have.

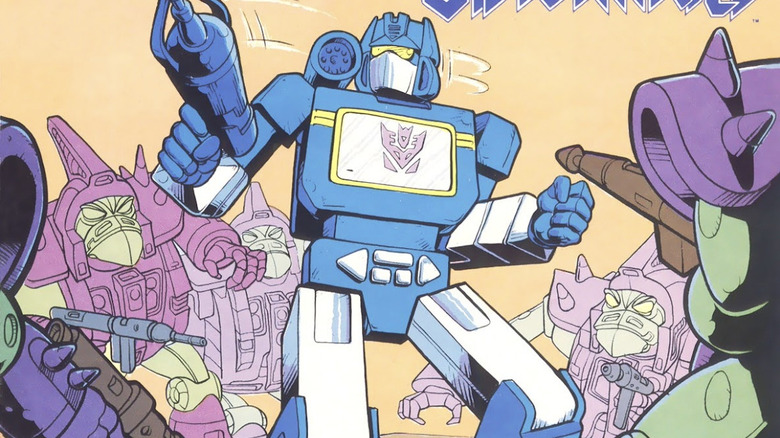

Soundwave sounds off

"The Transformers" was published by Marvel Comics in the U.S. for 80 issues and was initially written by Bob Budiansky. The comics were also published in the U.K., although that country was on a weekly release schedule, not a monthly one. So, to fill in the gaps, Marvel's UK branch had Simon Furman write fill-in stories while they awaited the U.S. issues (think of how anime series will make filler episodes to stall time for the manga to generate enough source material).

Amazingly, Furman's stories are generally the more heralded ones; it helps that he approached the concept of "Transformers" more seriously than Budiansky and his stories did. After Budiansky departed the series following the 55th issue, Furman took over from him, becoming the full-time writer of "The Transformers."

"Space Pirates!" (issues #182-187) is one of those UK-exclusive stories. Long story short, the warring Autobots and Decepticons team up to protect their homeworld, Cybertron, against malevolent aliens, the Quintessons. The Autobots are led by Ultra Magnus and the Decepticons by Soundwave, who has taken control with uncharacteristic braggadocio.

After the conflict is resolved, Ultra Magnus and Soundwave agree that they would have lost if they hadn't worked together. Soundwave ponders if there could be a permanent truce, but quickly decides there's too much bad blood (er, oil) for it to work.

Batman and Joker, sitting in a tree, L A U G H I N G

Both of these scenes show a rare glimpse of humanity from a villain who lacks it. The Joker is usually either a vicious sadist or a buffoon, while Soundwave is an emotionless spymaster; he's the Transformer who acts the most like a robot. Sullivan also lays out the page in six panels, much like Bolland did his. Two of the panels are nearly identical to "The Killing Joke" — Soundwave silently pondering with a shadowed Ultra Magnus on the left edge of the panel, followed by a close-up of Soundwave holding his head as the pained realization hits.

The arrangement is slightly different. In "The Killing Joke," these are the fifth and sixth panels; in "Transformers," they are the fourth and fifth. The page ends with a sixth panel of the Decepticons leaving and Ultra Magnus talking with another Autobot, Scattershot. The pair agree with Soundwave's tragic assessment the war can't be resolved peacefully.

"The Killing Joke" lasts a couple of pages longer. The Joker tells a joke about two patients who decide to escape a mental asylum together. They get to a wide gap between rooftops. One jumps across, the other doesn't because he's scared. As the Joker tells the punchline: "So then, the first guy has an idea. He says 'Hey! I have my flashlight with me! I'll shine it across the gap between the buildings. You can walk along the beam and join me!' But the second guy just shakes his head. He says 'What do you think I am? Crazy? You'd turn it off when I was halfway across!'"

With this, the Joker finally makes Batman crack a smile. The two share a laugh, Batman leaning on the Joker for support as hilarity overcomes him, and the book ends.

What is the Killing Joke?

In case you don't get it, Batman is the first inmate. He keeps one foot in the world of sanity and gives the Joker false hope of getting there too. The second inmate saying no represents the Joker turning down Batman's plea.

Famed comic writer Grant Morrison noted on Kevin Smith's "Fatman on Batman" podcast that the ending is meant to imply that Batman kills the Joker. That's why it's called "The Killing Joke," they argued. It's a compelling interpretation; in the opening of the book, Batman tells the Joker (really a body double) that they'll eventually kill each other if they continue fighting and he wants to stop that. Batman finally cracking would add to the tragedy.

The animated "Killing Joke" movie even gestures towards Morrison's reading. In that film's rendition of the ending, the Joker's laughter abruptly stops, as if Batman snapped his neck, and only Batman's laugh is heard as the film cuts to black. Such a hint can't be conveyed by a comic, which innately lacks sound.

However, for Moore, the ending is instead about Batman and the Joker sharing a moment of resignation. This does fit better with the joke preceding the ending. Moore explained on Goodreads:

"My intention at the end of ['The Killing Joke'] was to have the two characters simply experiencing a brief moment of lucidity in their ongoing very weird and probably fatal relationship with each other, reaching a moment where they both perceive the hell that they are in, and can only laugh at their preposterous situation."

Furman and Sullivan picked up on this. That's why their "Transformers" homage has the same theme of two adversaries resigned to eventually kill each other despite wishing that they couldn't.

A promise to transform

Take note of how Furman (via Soundwave) calls the Autobots and Decepticons different races. "Transformers" has always oscillated between this and whether they're two factions of the same people. I prefer the latter interpretation (it reduces the conflict if the Autobots are "programmed" to be good and the Decepticons to be evil), but earlier stories tended to go with the former. That might be why Furman writes the war as irreconcilable. Subsequent "Transformers" media has gone in different directions.

From 2005 to 2018, IDW Publishing printed "Transformers" comics set in one continuing universe. The revolving door of writers resulted in inconsistencies but the comics operate as an overarching narrative. The third major series (running from 2009 to 2011, written by Mike Costa and simply called "The Transformers") ends with the war concluding.

From there, IDW's "Transformers" comics (seven years' worth) were about the former Autobots and Decepticons trying to rebuild their shattered society. Characters and their allegiances became more fluid. Under the pen of John Barber, Soundwave — once the Decepticon ideal and Megatron's staunchest believer — became allies with Optimus Prime. In the concluding mini-series "Transformers: Unicron," they both give their lives to protect Earth.

The third Michael Bay "Transformers" movie, "Dark of the Moon" was supposed to end with Megatron calling for a truce by saying, "I have spent far too long destroying, and it has brought me nothing. Nothing. So I wish to try creating for a time and see if that brings me ... something." Optimus would have warily accepted, replying, "I want to believe it will be peace. I want to believe that he can truly transform. And I will hold out hope ... because in the end, that is all we have."

During production, however, this was changed to Optimus declining and then tearing off Megatron's head. You can read the original scene in Peter David's "Dark of the Moon" novelization.

Why Batman: The Killing Joke endures

"Space Pirates!" isn't the only time "Transformers" has referenced "The Killing Joke." A variant cover for "All Hail Megatron" issue #1 (drawn by Casey Coller, colored by Josh Burcham) replicates the "Killing Joke" cover (with the Joker holding a camera to his face and saying "Smile!"). In the homage, Megatron is holding Reflector (a Decepticon who transforms into a camera).

"The Killing Joke" is such a seminal comic (despite Moore's wishes otherwise) that it is hard to not see its influence everywhere, especially in Batman stories. If people are homaging your work six months after it's published, you've definitely left an impression. But what I think many people miss is that the moral center of the story is Jim Gordon, an ordinary-ish man caught in a battle between larger-than-life individuals. That's why the Joker tries to break him, not Batman, and he fails. Gordon's last scene is telling Batman not to kill the Joker: "We have to show him our way works!" This is a pretty idealistic conclusion no matter how foreboding Batman and the Joker's last conversation is.

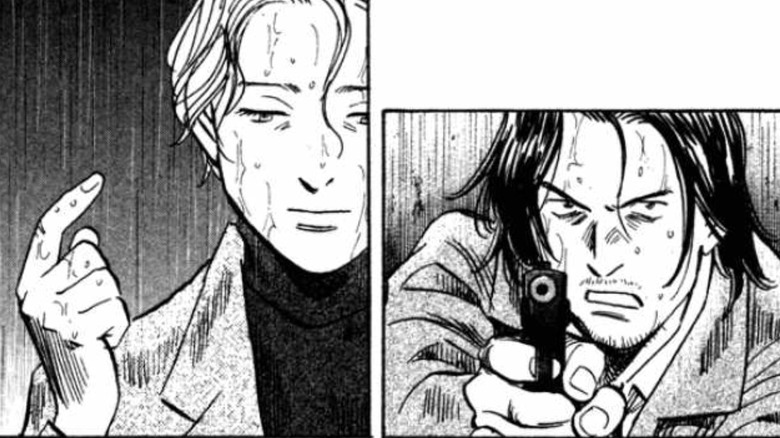

A comparison that's come to me recently is another of my favorite comics, the manga "Monster" by Naoki Urasawa. In "Monster," Dr. Kenzo Tenma is a surgeon hunting a serial killer, Johan Liebert, across Germany. When Johan was a boy, Tenma saved his life, and now he feels he must end it to save others.

What makes a Monster?

The central message of "Monster" is about the value of human life; as a doctor, Tenma has sworn to treat all lives equally, no matter the history, wealth, or actions of his patient. Tenma's journey makes him and the reader question if/when taking a life can be justified.

"Monster" is mostly inspired by "The Fugitive," but I also see some "Batman" in its hero-villain dynamic. Tenma operates in the same double bind as Batman when he fights the Joker. Murdering an evil man might be the pragmatic solution, but if he kills Johan, he proves his nihilistic philosophy correct and loses the moral argument. Similar to the Joker's fixation on Batman, Johan wants to corrupt Tenma by dying at his hand. In the story's climax, he tries to goad the doctor to kill him as part of "a perfect suicide."

I doubt it's an intentional homage, but the rainy atmosphere of Johan and Tenma's final confrontation cinches "The Killing Joke" comparison to me. The overlaps continue beyond the atmosphere into the thematic. Tenma ultimately upholds the sanctity of life in defiance of Johan, his arc ending much like Gordon's. Like the Joker, Johan also rejects a chance at forgiveness, saying it's too late for him.

Whether it's the Joker, the Decepticons, or Johan Liebert, a villain is only a villain if they refuse to transform into someone better.