How The Films Of 2022 Criticize Cinema While Celebrating It

Have you ever been on a film set? If you have, you know what a surreal experience it can be. Doesn't matter if you know the people making the movie or the material; the very nature of what goes on there, the hurry-up-and-wait work environment dedicated to capturing images and moments that are a willful fabrication of reality, is contradictory enough to create a mild existential crisis if considered too closely.

To put it in other words, such an environment is the quintessence of "movie magic." As unsettling as such a thing can be, it can also be transportive, with all the set building and costume designing and CGI coming together to create a more-real-than-real parallel world.

It's no wonder, then, that Hollywood has a long history of being enamored with itself. Other industries keep the machine of humanity perpetually chugging along, while the film industry and its ilk feed the soul, whether through reflecting our struggles back to us or allowing us the catharsis of escape.

Virtually every year, films about films are made, enough that the phrase "a love letter to cinema" has permanently entered the lexicon. While 2022 has been no different, a curious trend has emerged throughout this year's movies about movies: in the midst of celebrating cinema, they also seem to be struggling with the medium's relationship to real life. The filmmakers of '22 are not just in love with cinema's power but are also considering the ways people are affected by that power, whether directly or indirectly.

'But I'm a star!'

In broad terms, the allure of the silver screen is akin to the so-called American Dream: the notion that with enough hard work, talent, determination, and sheer force of will, one can achieve Hollywood stardom. As a result of this, there's a desperation that seeps into every casting call, a sick sort of delusion that has every aspiring performer erroneously thinking that they are the most deserving of a particular role. The cognitive dissonance of subsequent rejection — let alone failure — is enough to dislodge someone's sanity.

That's exactly what happens in Ti West's "Pearl," which sees the titular Texas farm girl (played by Mia Goth) faced with the cold reality that all the desire and ambition in the world isn't a guarantee that your celluloid dreams will come true. In West's companion film, "X," a now-elderly Pearl viciously stalks and murders a group of young filmmakers using her farm to make a porno, symbolically claiming revenge for her crushed dreams and the film industry's penchant for celebrating youth and shunning the elderly.

Just as harsh is Hollywood's fickle behavior toward artists who've previously found success. In Judd Apatow's "The Bubble," actress Carol Cobb (Karen Gillan) is forced to return to a franchise that made her famous, leading to a series of insulting incidents while filming that would never happen to a star. Even the cartoon heroes of "Chip 'n Dale: Rescue Rangers" find their nostalgic appeal makes them little more than corporate commodities, with the chipmunks discovering their old toon pals being turned into bootleg versions of themselves.

The perils of fame

The bitter irony, of course, is that having movie star fame is not all that it's cracked up to be, a theme that 2022's movies attacked with gusto.

The notion of someone who's achieved stardom by selling out is an old archetype, but such characters weren't dealing with mere ennui this year. Instead, as with George Diaz (John Leguizamo) in "The Menu" and Morgan Steel (Cam Gigandet) in "Violent Night," these folks who've compromised their artistic integrity meet some quite violent ends.

There was emotional violence brought upon movie stars this year, too. Biopics of celebrities have an ageless appeal thanks to mining and embellishing the tumultuous lives of their subjects, yet this year's "Blonde" and "Elvis" went beyond mere soap opera. In both films, directed by Andrew Dominik and Baz Luhrmann, respectively, the fates of Marilyn Monroe (Ana de Armas) and Elvis Presley (Austin Butler) are portrayed as inextricable from their public image. Neither movie purports to tell the quote-unquote "real" story of their subjects so much as metatextually examine how a human being can become a larger-than-life fiction and subsequently swallowed whole by the Hollywood machine, their very selves obliterated in favor of their legend.

The tension between having big-screen professional success and feeling personally lost could be seen in other films this year as well. In "The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent," Nicolas Cage (playing himself, naturally) is dealing with having his public image confront him in more ways than one, from fans expecting a lot of him to his younger self haunting him. In "Everything Everywhere All At Once," laundromat owner Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh) is introduced to the multiverse, and in one alternate reality she's a huge international movie star who finds herself lonely and regretful that she missed her chance at love.

Snakes in the Tinseltown grass

While issues of stardom, success, and fame have been explored for decades if not centuries, Hollywood is finally this year beginning to deal more openly with the monsters that it has allowed to operate behind the scenes.

Chief among these figures is Harvey Weinstein, and it's telling that the movie about his crimes isn't a tawdry biopic. Instead, "She Said," directed by Maria Schrader, follows journalists Megan Twohey (Carey Mulligan) and Jodi Kantor (Zoe Kazan) as they put together a story exposing Weinstein's long history of abuse and assault. Weinstein isn't so much a character in the movie (he's only heard a few times and seen once from behind) as he is a specter, a snake in the grass in a movie about the movie industry.

While Todd Field's "Tár" is about an artist working primarily in the music industry, it's revealed that Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett) did some scores for films during her apparently prolific career. Her very public cancellation and downfall may or may not be what happens to her in reality, with Field making the film increasingly subjective as it continues. Thus, "Tár" strikes directly at the dissonance of how an artist can insinuate themselves fully into the culture while just as totally find themselves shunned.

Zach Cregger's "Barbarian" has fun with its ambiguous title, applicable as it is to numerous characters within the film. Despite such folks like a creepy young man manipulating women into romantic dates, an abductor and torturer of women and a deranged killer, the movie's most odious figure is AJ Gilbride (Justin Long), an actor accused of sexual assault (which occurred by his own eventual admission) whose self-centered egotism only grows in monstrousness, earning him first place as the titular character.

For the fans

Though the enabling of power-mad abusers is something the film industry needs to continue to reckon with, there is also a growing cancer on the other side of the cinema screen in the form of the "fan." While films like 1971's "Play Misty for Me," 1990's "Misery" and numerous movies entitled "The Fan" have explored the topic of dangerous celebrity stalkers before, the more recent phenomenon of mobilized fandoms is becoming more disturbing, especially as they are now beginning to have an effect on the entertainment industry in a tangible way.

Given the franchise's penchant for using the effect of horror movies on fans as a theme, it's fitting that 2022's "Scream" explored this trend in the series' typically incisive, meta way. The characters revealed to be the killers are shown to be fans of the franchise's film-within-a-film series, "Stab," who met online and bonded over a mutual hatred of the latest sequel. While there's a little bit of hyperbole involved in equating homicidal psychopathy to hating a movie, given the death threats sent to critics and filmmakers from "fans" on a regular basis, it's not a stretch, either.

Out of control

As the fanatic fervor of movie "fans" proves, cinema is a powerful tool that may have massive, long-lasting effects totally unintended by the people who make films.

Damien Chazelle's "Babylon" states that the entire process of filmmaking and the machinery of Hollywood is akin to jazz music: artists trying to wrest control of something that is constantly threatening to go out of control. Like jazz, the film industry is as much improvisation as it is composition, with movies being made by people and a business that never quite knows what it's doing, resulting in a sort of alchemy.

Filmmaking also can have unintentional consequences, as demonstrated by a key scene in Steven Spielberg's "The Fabelmans." Young Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle) is editing a home movie he made of his family's recent camping trip, only in the process to discover a secret hidden within the footage that shocks him and begins to fully unravel his entire family.

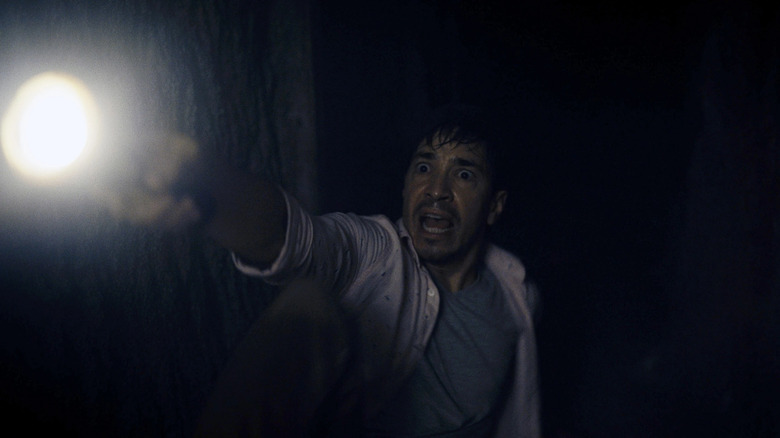

Jordan Peele's "Nope" also wrestles with this issue of cinema's power and how it can change based on who wields it. The film takes a look at exploitation within entertainment, exploring the subtle differences (and similarities) between using an animal on a sitcom and wrangling an extraterrestrial entity for a stage show, a creature that just happens to at times resemble a movie camera lens. Once the decision to point a camera at a subject has been made, "Nope" seems to say, there will be consequences.

Changing the horizon

Whether those consequences are good or bad is dependent on the people behind the lens. In a scene from Sam Mendes' "Empire of Light," projectionist Norman (Toby Jones) explains how the magic trick of motion pictures works by stringing together still images fast enough so that the human eye doesn't see the darkness between them. "Empire of Light" understands the moral duality of that statement, treating cinema as a wondrous place of transcendence that can become either a salve or a distraction from reality.

What the filmmakers of 2022 seem to be acknowledging is their own responsibility as artists, demonstrating how they are not taking the power and joy of cinema for granted. "Nope" sees Otis (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald (Keke Palmer) make that power work for them, exploiting something for entertainment for their own purposes without doing harm in the process. In "Babylon," Manny (Diego Calva) is magically transported by cinema after experiencing the harsh reality of what goes into making it. In "The Fabelmans," Sammy transmutes a high school bully into an idealized hero on screen, leading to that boy changing his ways for the better in real life as a result. Later, one of Sammy's cinematic heroes, John Ford (David Lynch), explains how making an interesting film involves the director wielding such power by literally changing where the horizon is in a shot.

As Chazelle said about "Babylon" recently, "I think of [this] movie as a poison pen hate letter to Hollywood, but a love letter to cinema. So there's a lot of s*** that goes into the industry, in the making, and the lives wrecked in order to make this thing, but something comes out of the other end that is undeniable and that humanity will always have to show for itself."

If "movie magic" is a real, quantifiable thing — and those of us who love the cinema believe it is — then, as with all magic in fiction and mythology, there is a cost for creating it. If the films of 2022 are any indication, Hollywood and the people who work within it are increasingly more aware of that truth.