The Fabelmans' Tony Kushner Speaks About Writing With Spielberg, The Power Of Art, And More [Exclusive Interview]

As singular an artist as Steven Spielberg is, his frequent collaborators-cum-repertory company help make his movies that much more well-rounded and powerful. From actors like Harrison Ford, Tom Cruise, and Tom Hanks to producing partners Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall to people like editor Michael Kahn and longtime composer John Williams, Spielberg's collection of fellow artists is not only well-varied, but impressive in their own right.

One such impressive member of the Spielberg team is writer Tony Kushner, who went from making a Spielberg reference in his Tony award-winning play "Angels in America" to becoming Spielberg's screenwriter on 2005's "Munich." Since then, Kushner wrote the screenplays for "Lincoln" and last year's "West Side Story," and with the exception of adapting "Angels in America" for HBO and August Wilson's play "Fences" for Denzel Washington's film version, Kushner's on-screen work has been for Steven Spielberg.

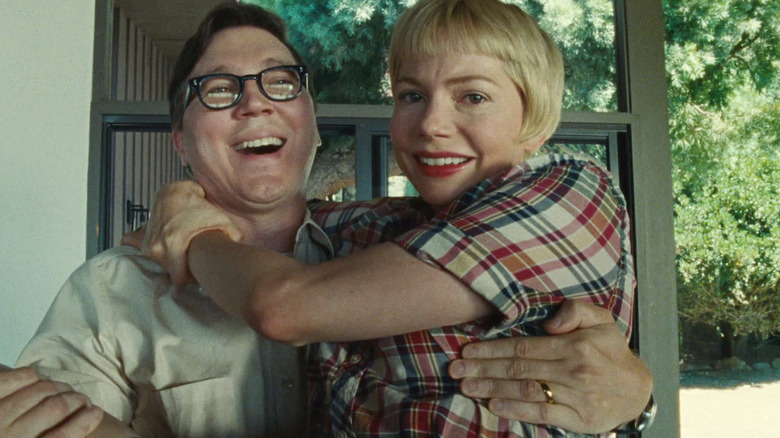

Perhaps that's why the filmmaker entrusted Kushner with collaborating together on "The Fabelmans," a fictionalized version of Spielberg's own coming-of-age story, in which budding director Sammy (Gabriel LaBelle) grows up in a household fraught with tension between his father, Burt (Paul Dano), and mother, Mitzi (Michelle Williams). "The Fabelmans" is a remarkable film that's part period piece, part divorce story, part nostalgic tale of falling in love with the arts, and part examination of the power of art itself, all of which is impressively nuanced.

I spoke with Kushner about the film on the eve of its limited release this weekend, and we talked about his experience working with Spielberg as a co-writer, how he approaches writing characters with contradictions, and the pragmatic wisdom of John Ford (played by David Lynch in the film!).

'The two of them put together would give you somebody quite a lot like Steven'

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

I absolutely loved the movie. Thank you so much for making it, as a lifelong Spielberg fan, movie buff, and lover of the way cinema affects people's lives and art in general, as well. You, as a screenwriter, have mostly worked with Spielberg on screen.

Except for my [Mike] Nichols days on "Angels in America." Mostly with Steven.

And "Fences."

And "Fences," yes.

You've done a lot of research for historical purposes on the previous Spielberg films. What was the research process for this like? Because of course he's right there as your co-writer.

That made some things a lot easier. He was my co-writer and we wrote the script together. So, he was literally right there.

I did some research, especially about Arnold Spielberg, Steven's father, and his years at RCA and General Electric especially, which were really fascinating. I learned that the guy was absolutely a prominent figure in the early history of 20th century post-war history of computing, and that some of the things that he did involving multiple users of a single system led directly to Apple and Microsoft. I mean, he was a really significant engineer, and that was thrilling to read about.

It was fun seeing this mother who was an artist, and, in her way, a born entertainer and a born performer and a galvanizer of people and charmer of people. And his father, who was a technical wizard and very practical-minded in a lot of ways and very quiet, but somebody who really knew how — I mean, he ran these huge workshops of engineers. You see the two of them put together would give you somebody quite a lot like Steven.

So, it was fascinating to get to spend that time with his memory of his parents. I met his father on a few of the film sets. I never met his mother, but I now feel like I knew her quite well.

'It had to be something that had universal meaning or we wouldn't have made it'

People are calling this — and I don't disagree — one of Spielberg's most personal films that he's ever made. But he's been so good over the course of his career in making what's personal for him so relatable to almost the whole world. I was wondering for you, when you were working on this, how much of yourself do you think you put into it? It's not just the Spielberg story ... or is it?

Well, I mean in a certain sense, the ways in which it's not the Spielberg story are the ways in which it's the Fabelmans' story. Because it's a work of fiction. I could make a little list of things from my life I stuck in just for the fun of it. Some of them I told him about, some of them I didn't.

But it really felt important to me that I didn't allow myself to push. As long as I felt that something was in the film or in our script that earned its place as an ingredient in a work of fiction, in the same way that any ingredient in any work of fiction has to earn its place — that it's not there just because you are fond of it — as long as I was confident that it was there for a reason.

Steven always — he's the director, so he gets the final word. But the reason I've worked with him for so long is that he lets me fight with him. If he didn't do that, I would've left a long time ago because I couldn't have done it. You can only collaborate if you can fight and if the fighting is productive. It's not just people fighting because they like to chew each other's faces off. But if it's really about making the work, caring very much about the work, and wanting it to be the best thing it can be, there's going to be heat generated and sometimes in anger or impatience or frustration or passion, and since our very beginnings in "Munich," he's really been willing to put up with a lot of kvetching for me and emails and texts and phone calls.

But with "The Fabelmans," I thought, okay, there is going to be some place here where I have to maybe be willing to stop a few places short of where I went on "West Side Story" or "Lincoln" or "Munich" to say, "This needs to feel to him like this really is true to his own lived experience." As long as it isn't meaningful only because of that. And he felt that, too. We both agreed, this had to be something that would work for people who didn't know that he directed it or who had never heard of him, if there are people like that. [laughs] It couldn't be one for his family or just for Spielberg fans. It had to be something that had universal meaning or we wouldn't have made it. And so, I really wanted to make sure that I never stepped too heavily on that. And I think, mostly, I feel like I succeeded in that vision.

'I don't know how you would write a character if you can't understand the way the character self-ideates'

You're so good with ensembles and nuance, and there's no one that I come away from this film going, "I don't like that person, I didn't understand where they were coming from." Even the bullies, though they're pretty odious, but I understand where they're coming from. Does that come naturally to you at this point in terms of your career, or is it something you work with and fight with, as you put it?

I've always felt like, I don't know how you would write a character if you can't understand the way the character self-ideates. How does the person straddle their own contradictions? I mean, unless they're psychotic, in which case they don't have to do that. This is why I don't think I really want to write Donald Trump as a character. I didn't want to write Ronald Reagan as a character, because I don't think there's any core coherence and I don't think they bother with it.

But most people, including people who behave pretty despicably, you have to think, "How does this person understand him or herself and what's their internal ego ideal? How do they explain the moments to themselves when they fail to live up to either their own standards or what we would consider more generally shared standards of decency and good behavior?"

The danger of that is it can lead you into a place where you're writing Nazis and trying to make people feel sorry for them. But — it's sort of an answer to your last question, too — there's a lot of me in everything I work on, because my job is to try and throw myself as deeply into the people [as I can]. When I'd gotten all these notes, I wrote this 81-page document for Steven of pulling all of his memories together into one continuous narrative just because I wanted to see if I could do it, and I didn't know if it was going to turn into anything. And I wrote this thing. What you have to do is think through, "This person is confronted with this, and then what do they do in reaction to this, and why do they do [it]?" as much, as deeply as you can imagine. "How do they think that this is going to get them what they want?" That's just the job.

I'm glad you feel that way about the two bullies. They're very different people, the two of them. And I was a little nervous because there was like, "Oh, here's a high school section, it's a high school movie we have to work in here, and there were these bullies." But I think we both approached it — I mean, they're in the movie because the main part of that story is from his memories. It's something that he told me. So the mysterious thing that happens at the end of that sequence, which I think is important to the whole film, we had to really think through why it turned out this way. When Steven was a kid and it happened to him, he's like Sammy in the movie: "What the f*** was that?"

I feel really happy about how resolved and unresolved its lessons are, because it's kind of a mystery, because it's about the power of art. There's the power of art that you can control the more you gain mastery of a particular form, and then there's the stuff that it does that you don't control and you have to learn a humility in the face of it. It is a real power in the world. It's not a direct power, but it's an enormous indirect power. And you have to recognize that you're playing around with something of enormous force in the world and you shouldn't kid yourself, even if you're Steven Spielberg, that you know exactly what will happen because you made this. I mean, that's when bad art gets made.

Wonderful things like the movies that he makes, there's a part of him that just says, "Go out in the world, and I hope what I'm putting in the world is a thing for the good rather than for the bad." And I think that's always been true. His work is, I think, for the good, but you have to surrender to the fact that you don't control it. And that, to me, in a way, became what the whole movie is really about. So I'm glad that you feel that way. We both are happy with the fact that there aren't villains in this story, especially in the central triangle.

'We were really lucky with that'

The divorce story, yeah.

It was just the truth. I mean, the thing that makes it tragic is that there are three people who, each one of those people loves each other very, very much. This is the father's best friend, and the best friend really loves Burt. And somebody's going to lose big and the other two are going to lose less big, but they're going to lose. I think the way that Michelle and Paul and Seth played that is simply superb. I mean, just with such subtlety and Michelle having to take this enormous character. And it's also a testament to Steven's direction that you have these two people who are, one of them is so huge and one of them is so quiet and self-contained and it builds up to this powerful heartbreak. And the two of them, they're just such astounding actors in all of what they do, and Seth Rogen, I mean he's amazing. So, we were really lucky with that.

'Make sure the horizon line is in the right place'

It's a wonderful film. It really captures for me — well, you can't capture all of what art "means," because that's absurd. But it captures the enormity of everything from the simplicity of John Ford being like, "The horizon's here," etc., and what the power of art can do to people in your real life. You can't predict it, you can't control it, as you said. And it's all of that and in-between.

And what Ford is saying is, "This is what you can do, is make sure the horizon line is in the right place." You look at those movies that this man made, which just blow your mind that one person did that. That's one of my favorite things in the whole film, is just that trip around the perimeter [in Ford's office] with "The Searchers" theme. And one of the reasons that I love that is the end [of the film]. One of the greatest artists, I think, of all time, and certainly one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, says, "There's one thing I can tell you: Learn the tools of your trade and good luck. Get the f*** out of my office!"

And get the f*** out of the theater! It's over!

"The Fabelmans" is now playing in select theaters, and opens everywhere on November 23, 2022.