Why You Need To Read Neil Gaiman's The Sandman Before The Netflix Series

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

If there's one title you're sure to find on just about every list of the all-time best comic books out there ... it's "Watchmen," because best-of lists tend to be kind of predictable and boring that way (at least the non-chaotic ones are). But just as there's value in reading Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' famous deconstruction of the superhero genre anyway, you should also seek out the other graphic novel we nerds love to go on and on about: Neil Gaiman's original run of "The Sandman."

Crafted by Gaiman in collaboration with a variety of talented comic book artists from 1989 to 1996, "The Sandman" is truly as layered and lyrical an attempt to grapple with the enormous complexities of existence, love, death, and dreams as any other graphic novel out there. Of course, if you're reading this, there's also a fair chance you've been told as much so many times that you're either scared to read it now for fear it can't possibly live up to all the hype, never had the time to make your way through Gaiman's tome (which spans 75 issues collected in 10 volumes), or gave up after being underwhelmed by its earlier chapters. Plus, with the live-action TV adaptation headed to Netflix, why bother at this stage?

These are all valid points. "The Sandman" is clunky starting out, and there's a lot of it to get through — and who the heck has that kind of leisure time these days other than the Endless, if even them? Still, as is usually the case with Gaiman's work (and, as Death might tell you, life itself), "The Sandman" is more about the journey than the destination. And the journey of reading Gaiman's daunting, dazzling, boundlessly imaginative saga is as unique to the comic book medium as they come.

Humble beginnings

"The Sandman" centers on Dream, the personification of dreams and a shape-shifting entity who's gone by many other names across eternity, most notably Morpheus. To quote Neil Gaiman's proposal for the comics from 1987 (which is featured in "The Absolute Sandman, Volume 1"):

He is not alive in the way we would understand living, nor could he ever die in the way we understand death. He exists because, since the first living being existed in the universe, there have been dreams, and in some obscure way, someone was needed to represent, personify, and control them.

Dream's real-world origins are, admittedly, less poetic. It began with Gaiman writing a treatment to reboot a 1970s DC Comics property called "The Sandman." Co-created by the legendary Jack Kirby, the series centers on the titular superhero, who battles monsters intent on attacking children through their nightmares. To his pleasant surprise, however, Gaiman would instead get the go-ahead to pen a brand-new comic under the same title.

For as different as these two versions of "The Sandman" would prove to be with time, Dream was not unlike a superhero himself starting out. Case in point, the first volume of "The Sandman" comics, "Preludes & Nocturnes," begins with Dream escaping captivity after being held captive for decades by a group of occultists who mistook him for his sister, Death. Upon finding that his kingdom, the Dreaming, has fallen into ruin in his absence, Dream sets out on a quest to recover three totems that are essential to his power in the hopes of rebuilding his domain. When you get down to the heart of the story, it's as basic a hero's journey as they come (albeit brought to life with Gaiman's elegant prose, coupled with his rich sense of horror and dark, disturbing fantasy).

Death and nightmares

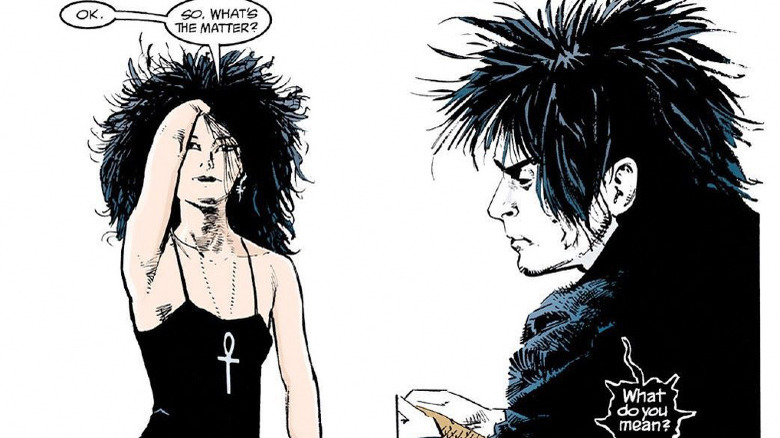

Reading them now, you get the sense that Neil Gaiman hadn't entirely figured out what he was aiming for with the earliest issues of "The Sandman," much less what his comics are about in a larger sense. Besides going a little overboard on the quasi-edgelord horror, these are the issues that play the most with the idea of Dream occupying the same reality as other major DC characters, to often clumsy results (save for John Constantine, who's gotten a fitting "upgrade" in "The Sandman" TV show). It's why there's an almost meta quality to the very last issue of "Preludes & Nocturnes," an epilogue in which Death shows up for the first time and pulls her brother out of the funk he's been in since completing his quest to regain his full powers. She pushes him to find a new purpose and even chucks a loaf of bread at the gloomy oaf's head for good measure.

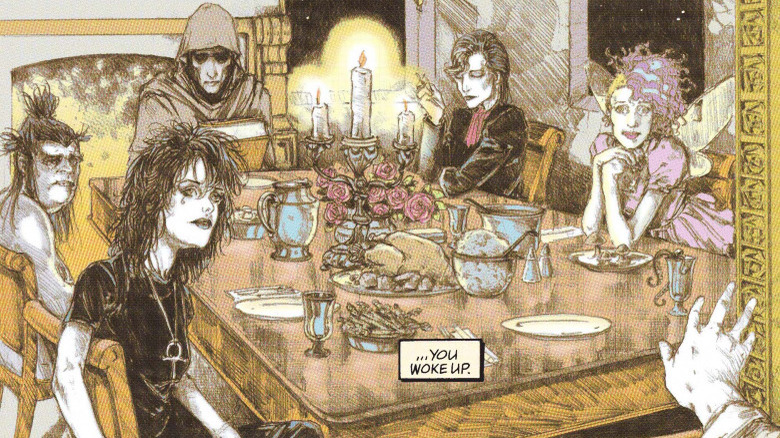

Gaiman, like Dream, took her advice and ramped up the world-building with the next set of issues (collected in "The Doll's House"), introducing the other members of Dream's ageless family (the Endless) along with key characters who would show up again and again in future stories (Queen Nada, Rose Walker, Hob Gadling), and a rather gnarly living nightmare in the form of the Corinthian (watch out for his eyes!). This is also where Dream's personal odyssey evolves from the material (collecting MacGuffins to drive the plot) to the existential, as he takes his first steps towards atoning for the many mistakes he's made across eternity while pondering that question all us mortals have to wrestle with at some point: Can I change for the better? In doing so, "The Sandman" goes from being full of promise to fully realizing its potential.

What Dreams may come

"Dream Country," the third volume of "The Sandman," finds Neil Gaiman evolving the very narrative fabric of his comic book series. Comprised of four short stories, these issues deconstruct the basic idea of what a "dream" even is and how the stories we tell about ourselves and our past can become more "real" than whatever actually happened. This, in turn, is where Gaiman begins to weave real-world mythologies into the tapestry of "The Sandman," uncovering new meaning in elements of classic Greek tragedy, transforming Element Girl from obscure DC superhero to a heart-breaking embodiment of the human experience, and even going so far as to make William Shakespeare a vital player in the saga of Dream.

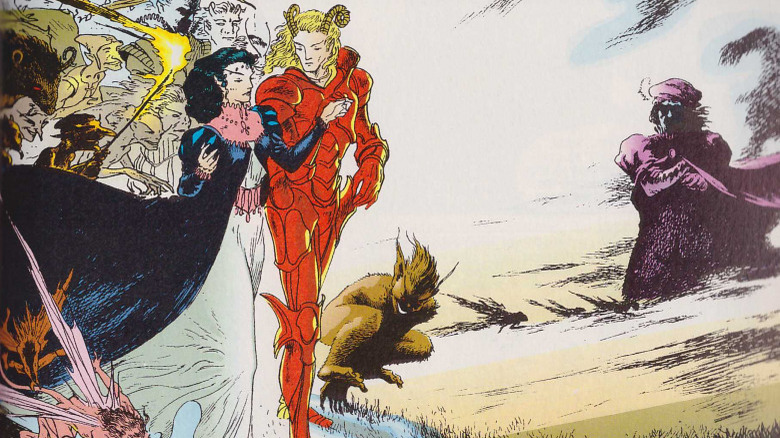

Gaiman's ambitions only grow from there. Later issues of "The Sandman" forgo a linear path in favor of a winding yet pointed trajectory. They also embrace ever-more-challenging subject matter, tackling what were, for their time, landmark queer stories and enriching what once seemed like trivial plot points and characters from issues past. The various trials and tribulations of Dream's dysfunctional family (or, as Gaiman might put it, "family") thusly become potent metaphors for our own earthly troubles. Themes about the fluidity of gender and identity and the never-ending struggle to find meaning in a finite universe only take on greater significance and poignance thanks to the presence of the Endless and the residents of The Dreaming.

The further along you delve into "The Sandman," the more the series begins to take on a distinct shape narratively. Every tangent or standalone subplot comes back around at some point, right down to those pesky DC Comics cameos from early on. It why the experience of reading Gaiman's comics as a whole is far more rewarding than trying to cherry-pick the best sections.

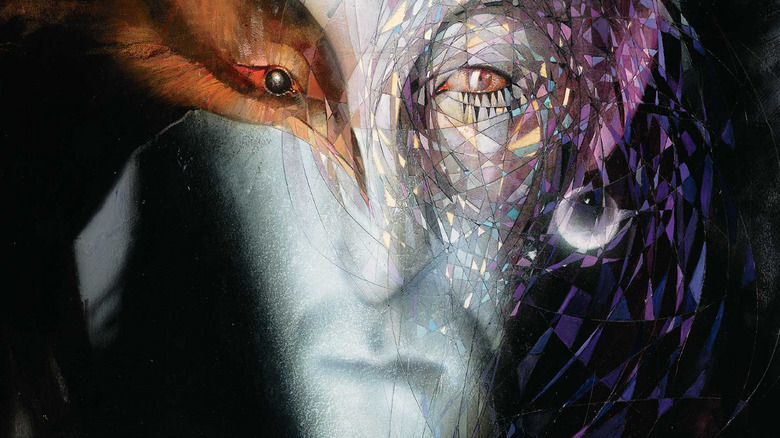

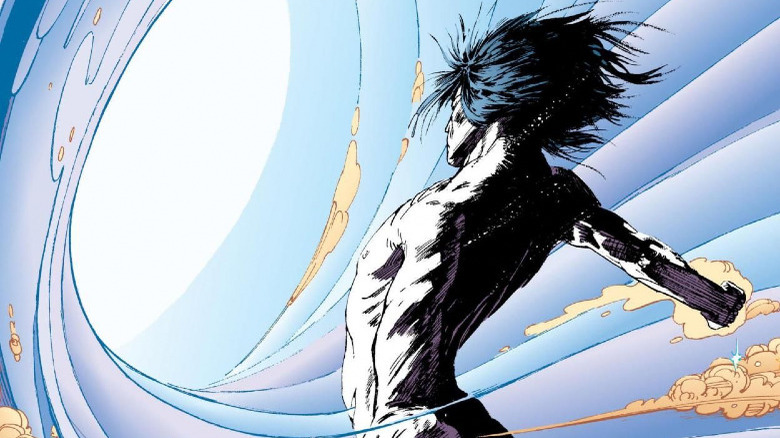

Elusive Dreams

Just as there are things a TV show can do that a comic book cannot (like turn your favorite characters into figures made of flesh and blood), Neil Gaiman is deliberate in the way he uses the comics medium to serve the stories of "The Sandman." The idea that Dream is never the same thing to any two living beings, and all which that implies, comes across beautifully over the course of the comics as different artists create their personal visions of Dream, the Endless, and the very act of Dreaming. The look and shape of these things ebb and flow depending on who's drawing them, with no two interpretations exactly alike. It's a quality that simply cannot be fully replicated or carried over into a live-action format, even with the digital tools available today.

This then asks a big question: Can the "Sandman" TV show ever hope (Dream?) of reaching and perhaps even surpassing the heights of its source material, flaws and all? For all the advantages it has (namely, being able to modernize aspects of the comics that haven't aged so well), that's quite the tall order. Gaiman's graphic novels grow ever more complex and meticulous in their design over time, in ways that parallel the trajectory of revered TV series like "The Wire." If that's not incentive enough to give "The Sandman" comics a shot however the TV show fares, then, well, like Destruction, I take leave of my post.

"The Sandman" TV series will premiere on Netflix on August 5, 2022. Gaiman's comic books are available to purchase from a variety of outlets, and might even be available to borrow from your local library. That's how I first read them many years ago, and I'd like to think Gaiman would be pleased to know that.