The 30 Best Detective Movies Ranked

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Detective movies and film noir became synonymous in the 1940s with films like "The Maltese Falcon" and "The Big Sleep." Both classics feature a rogue private eye played by film noir mainstay Humphrey Bogart, framed in dramatic shadows, as he plays a daring game of wits with femme fatales and scheming elites.

Of course, not all great noirs are detectives stories. "No Country For Old Men" isn't. "Drive" isn't. Noir visual style has become so standard in Hollywood moviemaking that basically every modern film deploys the genre's layered lighting scheme to create the illusion of depth. That's why all the best detective movies are also, visually at least, noirs. That includes the innovative live-action and animated hybrid "Who Framed Roger Rabbit."

Enigmatic stylishness aside, detective tales tug at something buried deep inside us. We crave both mystery and resolution. Whether it's a big city copper on the case like in "L.A. Confidential" or a citizen-detective like in "Memento," a puzzle plot methodically decoded by one determined investigator is a deeply satisfying brain game. And there's hardly a better catharsis than a cleverly linked succession of clues leading to one big reveal — as evidenced by how jilted we feel by a weak or inexplicable ending. Here are the best detective movies that deliver high cinematic style and a satisfying plot payoff.

30. Rear Window

New York summers must have been brutal before air conditioning was widely available. Even today, in the city's cramped courtyard apartments, summer means months of open windows and lots of detached intimacy between otherwise anonymous neighbors.

That's the premise of Alfred Hitchcock's 1954 film "Rear Window." Jimmy Stewart plays L.B. Jeffries ("Jeff" for short), a renowned photographer recuperating after breaking his leg on assignment. His boredom in convalescence leads to long hours of spying on his neighbors whose lives unfold outside his window. When he thinks he's witnessed a murder, his doting fiancée, played by Grace Kelly, believes him, but this peeping Tom detective needs more proof to persuade the police — and to catch the killer whose sights may now be set on him.

"Rear Window" is a remarkably provocative film for the era. Jeff makes up nicknames for all his neighbors, including a stunning young dancer often seen in states of undress whom he calls "Miss Torso." Kelly even parades before her laid-up cameraman in an elaborate nightgown she flirtatiously describes as "a preview of coming attractions." Public film screenings are often called "exhibitions," and the viewing experience is certainly an unmistakably voyeuristic act. Hitchcock, ever the playful cad with an unmistakably ironic wit, artfully constructed this remarkable thriller as a clever ode to the inherent vice of his own devious craft.

29. A Haunting in Venice

Flashy horror films and hard-boiled mystery-thrillers probably aren't the first thing that come to mind when you think of Kenneth Branagh. Be that as it may, the Oscar-winning Shakespeare enthusiast excels at making both, as anyone who's seen "Dead Again" (which is a total blast) and "Mary Shelley's Frankenstein" (which is an utter hoot) could tell you. Knowing that, it's not so surprising that "A Haunting in Venice" stands head and shoulders above Branagh's other movie adaptations of legendary whodunnit novelist Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot books so far.

The 2023 detective flick, itself loosely based on Christie's 1969 book "Hallowe'en Party," picks up with Branagh's Poirot following his investigations in "Murder on the Orient Express" and "Death on the Nile." Between those films and "Haunting," though, it's the latter that gives its mustachioed protagonist the meatiest arc, with Branagh's attentive sleuth now retired and struggling with the weight of all the death and misery he's witnessed when he's called upon to solve a murder mystery in a possibly haunted palazzo. "Haunting" allows Branagh the director to indulge his knack for showmanship, delivering a movie dripping with spooky atmosphere and tangible paranoia. Throw in a game cast that includes Tina Fey channeling Rosalind Russell in "His Girl Friday" as Poirot's fast-talking, not-so-strait-laced crime novelist pal Ariadne Oliver, and you've got the recipe for a grand ol' time.

28. High and Low

Akira Kurosawa's 1963 kidnapping thriller "High and Low" is a seething tale of class resentment. Toshiro Mifune plays Mr. Gondo, a wealthy shoe company executive whose son is unexpectedly kidnapped one morning. Gondo is ready to pay whatever ransom is required ... until he learns that the kidnapper made a mix-up and accidentally kidnapped the son of his chauffeur (Yutaka Sada). Gondo suddenly becomes a lot more objective about paying the ransom, revealing the exact point where his wealth overlaps with his morals.

The bulk of "High and Low" follows the police's investigation into the seedier parts of Yokohama as the police try to locate the kidnapper. Gondo literally lives above it all, occupying a rich house above the city where the impoverished can look up and seethe. Class resentment and crime can grow out of simple urban geography, it seems. The film climaxes with a confrontation between Gondo and the kidnapper (Tsutomu Yamazaki) where the latter admits why he targeted Gondo specifically. They find, in a very real sense, they resent each other.

Like most of Kurosawa's films, "High and Low" is emotionally intense yet gently humane, finding the human foibles and unfortunate habits that lead to our iniquity. Kurosawa constructed a terse, taut crime thriller that somehow feels pity for everyone involved. It's just another case of a masterful filmmaker mining unlikely humanity out of unexpected places. We don't like the kidnapper in the end, but we get it.

27. The Fugitive

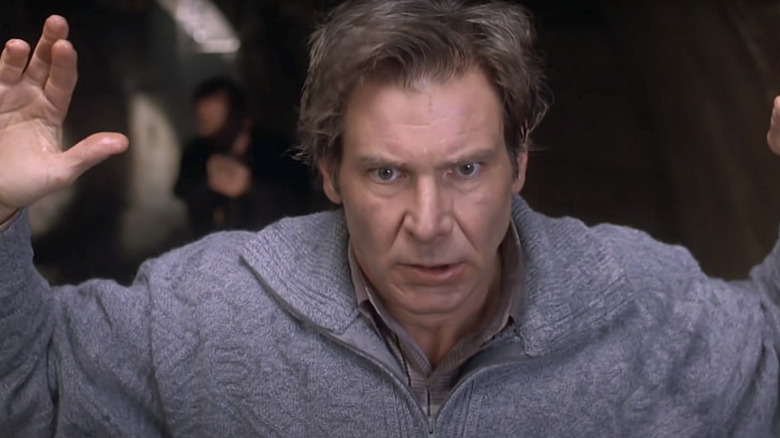

Harrison Ford dons an incredible beard in the opening act of the excellent 1993 remake of the 1960s TV series "The Fugitive." In the film, he stars as renowned doctor Richard Kimble, wrongly convicted of the brutal murder of his wife. When he makes an improbable escape, Kimble gets the chance to clear his name.

Warner Brothers apparently didn't like Ford's facial hair, even though the actor's thick greying whiskers do give him the distinguished look of an esteemed physician. As Ford explains in author Brad Duke's "Harrison Ford: The Films", the studio "paid for the face they wanted to see, so they were very concerned about that."

Of course, once Kimble is on the lamb, shaving becomes a plot-perfect disguise. But it's also symbolic of the good doctor's counterculture status. He's "slightly idiosyncratic, a character a bit outside the medical establishment," Ford explains. "The Fugitive" is a story about a morally upright citizen-detective who has to expose the corrupt medical establishment to find justice for himself and his patients. In 2020, real-world pharmaceutical giants were fined billions for pushing deadly drugs on a vulnerable public. As a partial result of this crime, U.S. life expectancy fell by the most since World War II. "The Fugitive" is mostly a thrilling popcorn movie, but it's also in Hollywood's tradition of skepticism about big pharma and the corrupting influence of all that cash.

26. Blade Runner

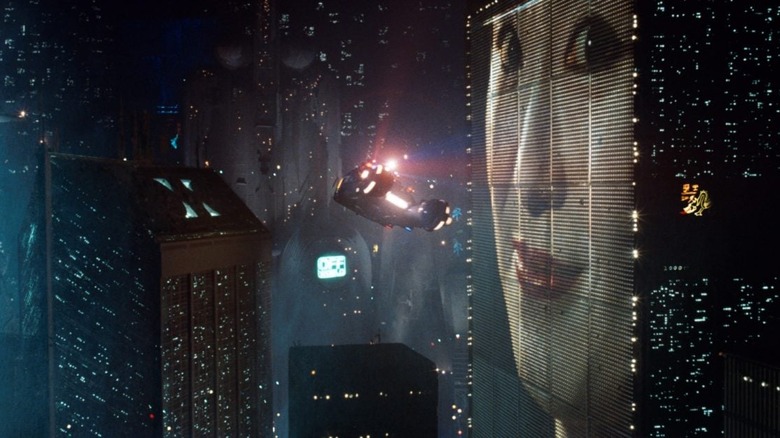

In 1982, Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" completely reset the look of dystopian futures in Hollywood films. Gone were all the symmetrically gleaming towers of white. Los Angeles becomes a bleak, sunless pit where a race of android slaves have gone rogue to be hunted down by Detective Rick Decker (Harrison Ford). In an excellent nod to the actual history of computer science, Decker distinguishes humans from outlaw androids by administering a rapid-fire digital Turing test.

Despite the fact Decker is tasked with taking on androids with superhuman strength, he works alone. He also lives alone in a futuristic but shadowy hovel where he drinks hard liquor and ruminates. Just as Scott had done three years earlier with the set design for "Alien," he creates a gritty and sopping wet future that is covered in the grime of the past — as it obviously would be.

"Blade Runner" is based in part on the heady 1968 novel "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?", which was initially set in 1992. The film's setting is moved to 2019, but both dates have obviously come and gone without even a whiff of flying cars or bipedal AI. However, given the rapid advancements in computer learning, the deeper question "Blade Runner" poses about what differentiates artificial minds from real ones, has never been more relevant. And Ridley Scott doesn't care whether you like it or not. (Gino Orlandini)

25. The French Connection

In the famous car chase from "The French Connection," a police detective played by Gene Hackman screams down busy New York streets. As he chases a train above, he blasts through red lights at speeds over 90 mph. Disturbingly, almost none of this was staged. Director William Friedkin ("The Exorcist") never closed down the streets for the stunt. The 15-minute scene was shot with no permits aside from a $40,000 bribe paid to a transit official. Friedkin simply goaded a stuntman to go for it and shot the whole thing over his shoulder. The incident has become famous in recent years as one of the most reckless acts of guerrilla filmmaking in Hollywood history.

The Oscar-winning film's often jittery handheld camerawork also gives it an intentionally gritty documentary feel. Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider (of "Jaws" fame) play a good-cop bad-cop detective team methodically tracking a heroin syndicate all the way to its source in France.

Friedkin explains on the film's commentary track he was interested in "the thin line between policeman and criminal." But it was the filmmaker himself who was crossing some lines. His movie was a smash and has endured as a classic, but he also rued his recklessness in 2021 as the film celebrated its 50th anniversary. "I was like Captain Ahab pursuing the whale," Friedkin told the New York Post. "As successful as the film was, I wouldn't do that now. I had put people's lives in danger."

24. Touch of Evil

Modern audiences may be shocked to witness how raw and horrifying Orson Welles' 1958 scuzz picture "Touch of Evil" is. Welles plays a cop named Quinlan who is slobby, alcoholic, racist, corrupt, and unredeemable. Quinlan is investigating a bomb blast, which captures the attention of a Mexican lawyer named Vargas (Charlton Heston, I know, I know). While observing Quinlan's investigation, Vargas finds that he plays dirty, planting evidence and generally manipulating cases. Vargas suspects that a lot of his old cases might have been tainted by Quinlan.

One of the central features of noir films and detective stories is that they take place in worlds without heroes. In film noir, decency is at an end, and humanity has entered a state of rot. That is certainly true in "Touch of Evil," a movie about police corruption, drugs, racism, and assault wherein the "old guard" is revealed to be bankrupt, morally incomplete, and happy to remain caked to the soul of humanity like mildew. Quinlan is Welles' attempt to tell an ACAB story, the white American cop brought down by an upstanding Mexican lawyer who will no longer stand for his willingness to be evil.

Even in 1958, the casting of Charlton Heston as a Mexican character was mocked. While Heston is a fine actor, the film might have been stronger had Welles been allowed to cast a Mexican actor. Heston was attached to the project before Welles came on board, though, so they were all stuck. It's a stroke of luck that the movie even got made.

23. Inherent Vice (2014)

Not all detectives are clever. Or perceptive. Or skilled. Or even capable of performing minor tasks without screwing up. Sometimes they're just lucky and know the right scumbags. This is the case of "Doc" Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) in Paul Thomas Anderson's "Inherent Vice," a detective story/stoner movie where a choose-your-own-adventure style makes it almost impossible to follow. Anderson's screenplay seems to have been made deliberately opaque, perhaps giving the viewer the sense of reading a Chandler novel while incredibly stoned. Most noir films are about greed or lust. "Inherent Vice" seems to make a virtue of sloth.

What is the plot? I couldn't say. There are several mysteries operating simultaneously and Doc rarely seems able to keep them apart. In many cases, a mysterious figure will approach him with information, rather than him having the wherewithal to ask for it. Like The Dude in "The Big Lebowski," Doc operates by bad instincts and weed-fueled powers, only getting by on sheer chance. He is a hippie in a world of straight-laced, hippie-hating cops.

"Inherent Vice" meanders through a landscape of detective movie tropes, looking at them with a bemused grin, unable to make sense of anything. While presumably a strange detective story, Anderson has made a wry comedy film of the highest order. By the film's end, Doc concludes that he has to solve at least one mystery lest he be remiss in his duties as a detective. He chooses the one story that would make for the most satisfying denouement and pursues it. The other threads are free to dangle in the wind.

22. Vertigo

Once considered the best film of all time (it was ranked #1 on Sight & Sound's decennial poll in 2012), Alfred Hitchcock's bona fide classic "Vertigo" is more about obsession than crime or murder. With his perfect framing and uncanny use of color, Hitchcock has created a dream space where reality seems to fall away, and a male's subconsciousness can roam free. Jimmy Stewart plays against type as Scottie a former cop who suffers from the titular affliction; when looking down from a great height, he becomes dizzy and disoriented. He investigates a friend's wife (Kim Novak) who is behaving ... oddly. She is obsessed with a dead woman in a portrait, and it's implied that she may be supernaturally possessed.

Scottie is eerily drawn to her despite her suicidal tendencies and creepy, death-twinged poetic language. The two don't so much fall in love but begin to cling to each other, both of them finding Goth-like kindred spirits. There is then a massive plot twist, and Scottie finds himself drawn to a second woman (also Novak) who looks uncannily like the first.

"Vertigo" is the investigation of a mystery, but, like "Blue Velvet" (see below), is more about its investigation into unknowable kinks. Hitchcock turned his aesthetic obsessions into a legitimate work of art. "Vertigo" is a spiral of confusion wrapped in a tight grey suit. It's uncomfortable and amazing.

21. Blow-Up

When looking up Michelangelo Antoninoi's 1966 film "Blow-Up" online, one might find it categorized as a "thriller," which couldn't be father from the truth. "Blow-Up" is a calm, deliberately inert film about characters who are stuck in an indifferent rut of hedonism and mod-hipster posturing. In it, David Hemmings plays a photographer whose life has become infected with a disaffected ennui (disaffected ennui being the default mode for Antonioni). He sleeps through one modeling session, making him late for another modeling session, making him bored, and causing him to wander off, leaving his models in a lurch. He barely pays attention to the world around him, relying on his camera to keep a record of the world.

While walking through a park, he takes a picture of a couple seemingly hooking up in public. He later finds out that the man he photographed ended up dead. In blowing up the photograph, he begins to find clues of foul play.

Know that the David Hemmings character isn't a detective, nor does he really have the wherewithal to actively solve a mystery. He merely becomes obsessed with details, using photos as a means of dissecting the past. And that, of course, could be said to be the very nature of photography. It's a record of something that can no longer be altered. The Hemmings character is trapped in a moment, and his activity in the present won't save anyone.

It's distant and disaffected, but golly is "Blow-Up" intriguing.

20. Clue

The word "impeccable" comes to mind.

Based on the popular board game (!), Jonathan Lynn's "Clue" is not only one of the best detective movies of its decade but also one of the funniest. "Clue" is stacked with comedic talent, boasting a cast that includes Madeline Kahn, Michael McKean, Leslie Ann Warren, Eileen Brannan, Martin Mull, and Christopher Lloyd. Tim Curry plays the butler in a mansion where blackmail will come to light and several murders will be committed. There are conspiracies, scandals, politics, and communism, all while the cast frantically races about the manse, committing pratfalls and kills with equal aplomb.

Cleverly, "Clue" was presented with three endings, part of the reason it went from box office flop to cult favorite. In its initial release, the separate endings were sent to different theaters, leaving the ultimate solution to the whodunnit impishly elusive; friends could compare notes and realize they were given different information ... inviting them to cross town and watch it again. That's a William Castle-level gimmick. Eventually, the three endings were included together in the film's home video releases.

The script for "Clue" is tight enough to allow for all three endings, keeping certain characters out of frame at the right moments so that their whereabouts can remain unclear during key murders. Each member of the cast is given a moment to shine, mug, overact, and get murderously outraged. It's not a spoof of murder mysteries. It's merely a great murder mystery that just happens to be amazingly funny.

19. The Third Man

"The Third Man" from 1949 is often considered the best British film ever made. Joseph Cotten plays Holly Martins, a pulpy western writer who arrives in Vienna to stay with his friend, Harry Lime(Orson Welles). When Martins discovers that Lime has died in a suspicious accident, he must become a citizen-detective to get to the bottom of a complex mystery.

The film has all the noir tropes. The excellent ensemble cast immediately feels allied against Martins and his effort to find answers. He even falls for the grieving girlfriend of his dead best friend. Forbidden love is often key to the genre and pushes its heroes into a choice between their desires and their conscience. This is also a story about post-war Europe. The wartime corruption portrayed in films like "Casablanca" continues here, as a shadowy black market has taken root in the ruins of a once-great city.

Aside from "Citizen Kane," "The Third Man" is Orson Welles' best role, one that he reprised for a radio show. The difficult auteur-actor certainly lived up to his diva reputation on set. He showed up two weeks late and then flat out refused to shoot a crucial scene. This forced overworked director Carol Reed to later recreate a complex set and shoot around a body double. Reed's grueling production schedule led to an amphetamine addiction as the director struggled to finish his masterpiece on budget.

18. Memento

One of the keys to enjoying "Memento" is to avoid watching it with that irritating subset of cinema-hating trolls whom Alfred Hitchock famously dubbed "the plausibles." This consortium of plot cops isn't interested in the language of film. Interested only in poking holes, they watch movies as superficially as possible. It's particularly aggravating to sit through a sci-fi or fantasy film with one of these critics. There could be winged pigs orbiting Mars at the speed of light, and they'd pipe up with some quibble about how all these swine found such form-fitting space suits.

My point is incoming. Wait for it. In Christopher Nolan's "Memento," Guy Pearce plays a man who loses his ability to make short-term memories after witnessing the brutal murder of his wife. Despite the disability, he's hellbent on tracking down her killer, but his only clues are scribbled on the backs of polaroids or carved into his flesh.

Enter "the plausibles": "How does he remember that he has no memory?" or "How does he remember his wife is dead?" they gleefully retort, desperately sure they've thought of something Nolan hasn't. In this situation, you can either call your primary care provider and ask for a referral to a neurologist for a scientific explanation — or you could just enjoy one of the most inventive and engrossing modern noirs ever made.

17. The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo

David Fincher's stylish 2011 remake of "The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo" starring Rooney Mara and Daniel Craig certainly has all the director's signature polish: the emotionally intuitive camera movements, the beautifully coordinated noir colors, and of course, the artistic framing with all the right symmetry and leading lines that scream high-end Hollywood cinema. And yet, Hollywood's foremost formal stylist seems somewhat uninspired in this redundant effort to cash in on an overseas hit.

Based on the mega-bestselling mysteries by Swedish journalist-turned-novelist Stieg Larsson, the original 2009 film adaptation starring Naomi Rapace is the more engrossing film. It follows the travails of orphaned hacker Lisbeth Salander who teams up with a disgraced reporter. This odd couple finds redemption as they investigate the cold case disappearance of an heiress with dark secrets.

There's nothing wrong with the American remake, but there's just something so characteristically Swedish about the source material that the farther afield it goes, the less it resonates.

16. Blue Velvet

After making an adaptation of "Dune" in 1984, David Lynch was disillusioned by the studio system. He returned to cinemas in 1986 with what would prove to be one of the best films of the decade. "Blue Velvet" is a kidnapping story (some believe it to be a confusing one) that involves a missing child, a severed human ear, and unexpectedly enjoyable kink. Kyle McLachlan plays a college kid named Jeffrey Beaumont who has returned to the placid, cartoonishly wholesome hometown to see his ailing father. While walking home from the hospital, he finds a severed ear in a field. The ear leads him to investigate crime and corruption in Lumberton, revealing an aggressively seedy underbelly, and into the arms of Dorothy Valens (Isabella Rossellini). Dorothy is a sultry lounge singer who is being kept in slavery by the demonic Frank (Dennis Hopper), one of cinema's scariest villains.

Lynch has said in interviews that he loves being lost in mysteries, so much so that he hates finding their solutions. "Blue Velvet," then, isn't so much about figuring out a crime or solving a kidnapping, but finding ways to be lost in the shadows of a seemingly bright place. Lynch can see right through the veil of decency draped over Rockwellian Americana, finding violence, kink, murder, and rot beneath. Lynch's camera lingers on a well-maintained lawn before dipping under the dirt to see horrifying insects writhing underneath. Jeffrey doesn't discover a crime, he discovers that vice and evil undergirds everything.

15. Se7en

David Fincher's 1995 noir masterpiece "Se7en" is one of those rare timeless films you can confidently share with younger thriller fans. Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman as police detectives tracking down an Old Testament-inspired serial killer have such a tense and conflict-ridden chemistry that their contentious bromance blooms right to that legendary twist ending.

When "Se7en" came out, the critic at my local newspaper (who shall go unnamed) didn't like the film. He dismissed it as too grim — too visually dark even. I managed to get him on the phone for a school project, and he stood by the review. He just didn't get it.

"Se7en" certainly pushed the noir envelope into gruesome new terrain, its graphic radicalism has helped it stay fresh all these years (and countless "Saw" films) later. However, it's really the script's procedural tautness on top of gorgeous sets and moody modern cinematography that assures it ages so well.

Fincher, who filmed Se7en in sunny southern California, dumps a biblical flood of rainwater on his shots, convincingly transforming the City of Angels into a muck-mired Gothic hellscape. This gritty thriller about urban decay was ironically made at the height of America's booming post-Cold War suburban prosperity. It was a triumphantly hegemonic moment that one intellectual prematurely dubbed "the end of history." Maybe that's why some critics initially found "Se7en" needlessly nihilistic. Multiple bleak decades later, Fincher's best film feels downright prophetic.

14. Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Robert Zemeckis' "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" is a classic showbiz noir about corruption in 1940s Hollywood. There is a femme fatale wife, a clueless actor, a greedy studio head, and a mysterious judge/enforcer who seems to carry an inherent streak of murderous racism. In a twist, the Hollywood stars are all cartoons who just happen to live in the same 3D space as humans. Zemeckis employed every trick in the VFX book to make it look like cartoons were actually living alongside actors like Bob Hoskins and Christopher Lloyd, and he won a special Academy Award for his efforts. The animation is whimsical and dazzling, and cartoons are able to pick up and interact with live-action objects with utter realism.

Looking past the effects, however, one might find a tightly scripted classic film noir about a wounded Eddie Valiant (Hoskins) and his deep dive into "Chinatown"-like city corruption. Someone, Eddie finds, wants to bulldoze the ghetto for nefarious purposes. In this universe, though, the ghetto is Toontown, an animated sub-city. Hoskins is perfect as Eddie, a Chandler-esque alcoholic detective, who convincingly interacts with Roger Rabbit (Charles Fleischer), a cartoon framed for the murder of Marvin Acme (Stubby Kaye).

It's too easy to be dazzled by the effects in "Who Framed Roger Rabbit," and one can watch it many times just to gaze at the spectacle. The uncanny thing about the film is how well it plays as a detective mystery.

13. Brick

Rian Johnson's 2005 feature debut, "Brick," is a meta-noir in the tongue-in-cheek style of "The Third Man" that envelopes a bunch of high school kids who all seem to know how to play their archetypal parts. The director has these teens emulating Humphrey Bogart, talking in laconic, pithy bursts which never give away too much of the plot. The stylized conceit feels odd coming from the mouth of babes and is an amusing way to highlight the tropes that have long been the basis of the detective genre.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt plays Brendan Frye, an upperclassman trying to figure out who killed his girlfriend (Emilie de Ravin). He's a loving parody of noir anti-hero detectives, but with little of the signature bad boy swagger. He's got the wise-cracking patter down as he spars with one reluctant witness after another. But he's simultaneously an awkward, fluffy-headed teen with a shy habit of stuffing his hands deep into his pockets. If you don't get Johnson's joke about the earth-shattering self-seriousness of teenage life, this admittedly low-budget flick is going to seem clunky and oddly old-fashioned.

12. Zodiac

In 2021, true-crime obsessives seemed to have cause to celebrate when a team of cold case detectives claimed to have finally identified the Zodiac Killer, a mysterious serial murderer who haunted San Francisco in the late 1960s and early 70s. For decades, cryptologists have puzzled over the ciphers this monster first sent to Bay Area newspapers in 1969. There have been many suspects, but the codebreakers claimed to have finally unscrambled the missives, identifying Zodiac as Gary Francis Poste, a supposed rural gang leader who died in 2018.

David Fincher's masterful and suspenseful "Zodiac" from 2007 didn't have this seemingly plausible answer to incorporate. And that's a good thing. The film isn't about answers but rather an obsession with a mystery that produced nothing but dead ends for decades.

Jake Gyllenhaal plays Robert Graysmith, a cartoonist at the San Francisco Chronicle which was one of the newspapers that really did receive these taunting ciphers. Graysmith's handiness as a cryptologist leads to a life-destroying (but weirdly understandable) fixation. Like all of Fincher's work, "Zodiac" is technically brilliant, but it's also a remarkably restrained mood piece about the psychological toll of this long-unsolved mystery.

11. Knives Out

"Knives Out" has a handy clue generator that must be every detective's dream: a key witness (played by Ana de Armas) who gets physically sick to her stomach when she lies.

This "Clue" style detective comedy is about the strange death of a wealthy mystery novelist (Christopher Plumber). He's the patriarch of a scheming family of ingrates living off his largesse. Everyone is a suspect. Daniel Craig ditches his native British accent for an exaggeratedly slow southern drawl as his character, Benoit Blanc, methodically works through the riddle.

"Knives Out" is the creation of writer-director Rian Johnson, the auteur responsible for the controversial "Star Wars: The Last Jedi." Johnson deserves credit for hilariously triggering that franchise's fanboys, who have demanded Disney turn the once spiritual endeavor into a soulless, repetitive, information-culture Easter egg hunt for nostalgic callbacks. He's also the genius behind the low-budget sci-fi masterpiece "Looper." In other words, he's a rebel and a storyboard craftsman, which is why this turned out to be one of the best murder mysteries ever. In "Knives Out," he uses his suspicion of establishment consensus and his knack for tightly-wound plots to construct a clever critique of bourgeoise hypocrisy. De Armas is delightful as the film's working-class conscience, and her chronic nausea is perfectly understandable given the company she keeps.

10. The Silence of The Lambs

In "The Silence of the Lambs," Jodie Foster's slightness of frame is one of many features that made Clarice Starling the perfect FBI trainee to help track down Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine), a serial killer who skins his victims in a twisted quest for self-transcendence. The opening credits show the five-foot-three Foster training at Quantico as she scrambles through a creepy obstacle course — a metaphor for her coming journey. In a subsequent shot, she's comically dwarfed by her mostly male colleagues in an elevator. When she's tapped to interview the imprisoned cannibal psychiatrist Hannibal Lecter, who may have known Buffalo Bill, it becomes clear she only got the job because her perceived vulnerability will be attractive to the predatory doctor.

Foster's Clarice Starling isn't just a dogged and clever detective. She's also facing a male-dominated law-enforcement establishment that ultimately needs her perspective. It's Starling's understanding of what it's like to be a young woman (along with Lecter's taunting insights) that reveals the crucial final clue.

This added subtext deepens "The Silence of the Lambs" and is no doubt part of why a film that is essentially a gruesome horror thriller somehow nabbed five Academy Awards, including best picture and best actress for Foster's outstanding performance. "The Silence of the Lambs" is on the Mt. Rushmore of modern thrillers and deservedly so. It's every bit as engrossing, eerie, and relevant as it was in 1991, even if it stirred up some controversy in the years since.

9. L.A. Confidential

"L.A. Confidential" borrows heavily from the themes of Roman Polanski's "Chinatown" and paints a picture of the City of Angels, circa 1953, as corrupt right down to its foundation. The local media is nothing but sensationalist. pay-for-play trash and the police department is bought off, filled with racists, and brutal. As in "Chinatown," the city's elites stand above.

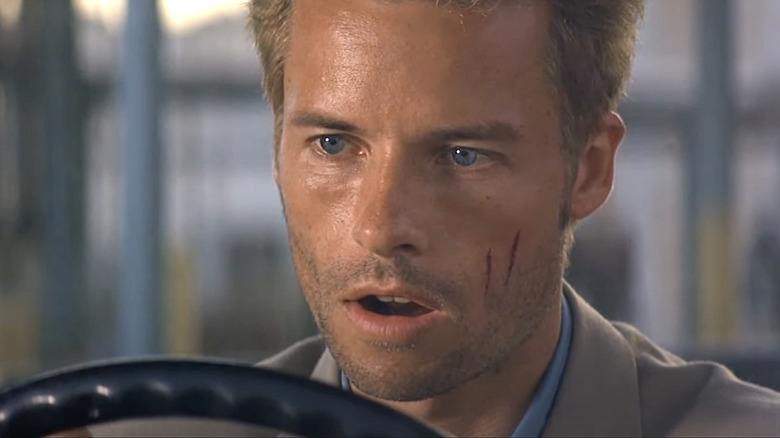

The phenomenal Guy Pearce plays an ambitious cop named Exley. The son of a murdered police officer, he's dead set on making his name and avenging his father. When Exley tries to clean up his own corrupt cop shop, he's pitted against a conflicted old-school hardliner with a hair-trigger temper (Russell Crowe). The tension between Pearce and Crowe is cut with Kevin Spacey as a glib flatfoot who spends his public-funded workdays consulting for Hollywood productions and feeding self-serving gossip to local tabloids.

"L.A. Confidential" has all the elements of classic film noirs but with the technical mastery of modern, big-budget filmmaking. It was produced at that brief '90s peak of perfectly exposed film stock just before a decade of regression as the kinks were worked out with digital cameras. It's the high culmination of half a century of this storytelling style and probably the most entertaining flick in the classic noir style ever made. In fact, Rotten Tomatoes ratings have resulted in it being called the best movie of all time, even if their reasoning is inherently flawed.

8. The Thin Man

The labyrinthine mystery at the heart of "The Thin Man" is eventually explained in grand fashion during the movie's climax at a fancy dinner party with all of the suspects attending. The ins and outs of who did what, when, and why are sometimes hard to track, but luckily, it's so much fun spending time with the two leads that those details become secondary. The vibes are off the charts in this film, thanks largely to the rat-a-tat dialogue and the ultra-charismatic performances of dynamic duo William Powell and Myrna Loy.

While many detective stories center on a loner private eye who numbs his problems with alcohol, this one focuses on a married couple, Nick and Nora Charles, who absolutely relish the act of drinking. (They seem to always have a glass in their hands, and Nora always makes sure to match Nick drink for drink.) They're also madly in love with each other, joking around and showing affection in a way that still feels rare on screen today. Audiences fell in love with them in a big way — this film spawned five sequels, and Powell and Loy starred in all of them.

Nick Charles is a retired detective who has since married rich (Nora's family is loaded), and the two of them visit New York City for the holidays, only for Nick to get roped into the aftermath of a murder. Husband and wife team up to solve the crime, drinks flow freely, and a lighthearted, ebullient time is had by all ... except the killer.

7. The Long Goodbye (1973)

Robert Altman's "The Long Goodbye" is based on the famed 1953 novel by Raymond Chandler, but it's perhaps the least hard-boiled detective movie one might encounter. Call it a soft-boiled detective story. Detective Philip Marlowe is reimagined by Altman to be a terminally casual Elliott Gould, a man who seems more weary and put-upon than grizzled and nihilistic. The film's opening scenes feature Marlowe going to a convenience store in the middle of the night to get the exact right brand of cat food for his cat, hoping to fool the feline by transferring Brand X into emty cans of the cat's favorite.

The story is merely mystery Chandler's twisted tale of scratched faces, trips to Tijuana, drowned millionaires, and murdered friends, but Altman's naturalism robs a typical detective story of its usual noir-ish style, leaving audiences with something weirdly affable and casual. Marlowe eventually finds himself delving a little too deeply into L.A.'s iniquities and finds himself being marked by the darkness.

Somehow "The Long Goodbye" plays, simultaneously, like a decent entry in 1970s neo-noirs and a satire of the genre. What if a laid-back '70s dude, ensconced in an apartment that overlooks a cult of lesbian New-Age nudists, took the place of a hard-fisted character like Philip Marlowe? Somehow, through the satire, "The Long Goodbye" transcends, transforming it into something truly great. "The Long Goodbye" was adapted for TV in 1954, bu for my money, Gould is the best to have played the part.

6. Memories of Murder

If you like "Zodiac" (and you should, because "Zodiac" is great), then you definitely need to check out Bong Joon-ho's "Memories of Murder." Set primarily in the late 1980s, "Memories of Murder" follows a group of cops trying to catch a serial killer targeting women in Hwaseong. That may sound like the recipe for a standard crime thriller, but Bong instead creates a fascinating picture of obsession. As the crimes continue, the detectives trying to crack it grow more desperate.

Bong drew on a real-life series of crimes for the inspiration for the film, and did extensive, exhaustive research when he was writing the film. "Once I decided to make the film I started to do a huge amount of research," he told BFI. "I became obsessed with the facts of the case. I went through all the newspaper reports and then began making interviews with people who'd been involved: journalists, detectives, townspeople who had lived there at the time."

If you're expecting a typical thriller here — one where the cops prevail and justice is served — you're in for a shock. Like "Zodiac," "Memories of Murder" isn't really about solving the crimes. It's about how the crimes have a rippling effect, influencing everyone around them and turning lives upside down in the process.

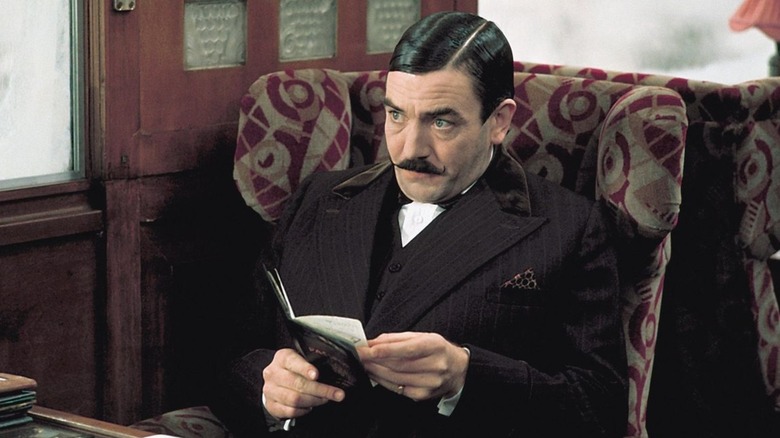

5. Murder on the Orient Express

Sidney Lumet's 1974 adaptation of Agatha Christie's 1934 novel might be the golden standard by which all other detective movies must be measured. The locked-in setting — on board a train — keeps the investigative action tight and terse, leaving viewers eagerly looking for clues, trying to solve the mystery themselves. Of course, even the wisest viewer is going to be a few steps behind the eccentric and whimsical Hercule Poirot (Albert Finney), a fastidious Belgian with an observational eye and a collection of personal quirks; he wears a specialized mustache-holder to bed.

Poirot is also surrounded by a rogue's gallery of suspects, played by some of the biggest movie stars of the day. Among the suspects suspected of murdering a gangster named Ratchett (Richard Widmark) are Lauren Bacall, John Gielgud, Sean Connery, Ingrid Bergman, Tony Perkins, Michael York, Vanessa Redgrave, Jacqueline Bisset, and Martin Balsam. As in all good murder mysteries, every one of the characters has a motive, a means, and an opportunity to have committed the murder. It's just a matter of sussing out which one of them might have done it. The actual solution is ... well, I would never dare imply the true identity of the murderer, but I will say that a casual viewer will not be able to predict it.

Hercule Poirot is one of the more colorful characters in the history of detective fiction (and certainly one of the best detectives on screen), and Finney brings a lot of comedic energy to the role without sacrificing his intellect or sternness. Lumet winds his movie tight as a drum, keeping a viewer intrigued to the last frame.

4. Chinatown

Roman Polanski's "Chinatown" may be somewhat overrated by the old guard since it emerged from Hollywood's vaunted sudden turn towards experimentation in the 1970s. But this twisty tale of Los Angeles corruption remains worthy of praise, particularly for Jack Nicholson's excellent lead performance. Nicholson never officially retired, but he hasn't appeared onscreen since 2010. "Chinatown," however, is among the best artifacts of his youthful greatness

Nicholson plays Jake Gittes, a Los Angeles private eye. In a classic noir call to action, a suspicious woman (Faye Dunaway) bursts into his office and wants to hire him to look into her husband. When it turns out she's an imposter, Gittes uncovers the lurid corruption that made it possible to build a city atop a parched California desert in the first place.

If you do get down on "Chinatown," take note that "The Maltese Falcon" director John Huston plays the film's ruthless villain. He's a powerful menace and central to the film's sickening final twist as Polanski faithfully recreates the genre style that Huston basically invented. For fans of noir, this fact alone makes "Chinatown" essential viewing.

3. The Big Sleep

Fans are still active online, puzzling over the intricate and confusing plot points of "The Big Sleep." It's a testament to the staying power of director Howard Hawks' 1946 adaptation of hard-boiled detective writer Raymond Chandler's novel. Hawks himself was famously so confused by the plot during filming that he called up the author for help, but Chandler was stumped too.

Humphrey Bogart plays private eye Phillip Marlowe who is hired to help a young woman deal with a gambling debt. Nothing is ever what it seems in noir, though, and soon he's pulled into a thicket of underworld deviance from blackmail schemes to murder. Bogart's excellent co-star is, of course, Lauren Bacall whom he would wed just months after filming concluded.

Bogey's fast-talking style is iconic but also part of what makes him a difficult guide through the rapid revelations of names and places as the mystery escalates. "The Big Sleep" is a genuine intellectual challenge where the detective work really falls on the audience.

2. Laura

Hard-boiled film noirs were once known as "melodramas" in old Hollywood, two genres that have very different connotations today. One film that could still fit into both categories is "Laura," Otto Preminger's 1944 mystery film. The titular character, played by Gene Tierney, is a murder victim. NYPD Detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) is assigned to investigate and interviews Laura's loved ones. The movie, a tight 88 minutes, is bifurcated. The first half is mostly flashbacks; the mystery of Laura's murder is a framing device so we can learn about her. Then the movie completely changes halfway through, for McPherson has been investigating the wrong mystery.

"Laura" was first a novel (by Vera Caspary) published in 1943, only a year before the film premiered. The Old Hollywood pumped out black-and-white "melodramas" like a factory, but the sublime style of "Laura" is an easy example for how these cheap pulp films became classy noir. Roger Ebert wrote that "Laura" is a film you remember, but not for its story. No, the things that stay with you are David Raskin's sweeping theme for Laura herself, or the performances (including Tierney as no mere femme fatale, and a young Vincent Price as a red herring).

An ancestor to "Vertigo" and Tony Scott's "Deja Vu," "Laura" is a mystery and a tragic romance where the detective is falling for a woman he already believes dead.

1. The Maltese Falcon

In The Hollywood Reporter's original 1941 review of director John Huston's "The Maltese Falcon," the film's stylized performances are praised as "strikingly natural." To modern eyes, Humphrey Bogart's fast-talking turn as private detective Sam Spade is anything but naturalistic.

"The Maltese Falcon" has gone down in film history because it is so purposely stylized. The film's innovative shadowy cinematography, borrowed from German expressionism, basically created the film noir aesthetic. Shades of this gritty style can be seen in every movie on this list.

The Hollywood Reporter also amusingly digs at Huston contemporary Alfred Hitchcock's heady hang-ups, noting that "The Maltese Falcon" is "blessedly lacking in psychological implications." American critics of this era somewhat underrated Hitchcock, who was being hailed as a genius in France. Hollywood watchers, meanwhile, were of practical mind and rooting for American films to be entertaining and competent. "The Maltese Falcon" is both, but it's also a historically significant time capsule of classic Hollywood values. Much like chivalric cowboys of the Western genre, Spade is the quintessential rugged individual. He's a street-wise rebel, working just outside the law.