Why We'll Never See Akira Kurosawa's Original Version Of The Idiot

"The Idiot" was Akira Kurosawa's 12th feature film as a director, and was released in 1951 in-between his more celebrated masterworks "Rashomon" and "Ikiru." The film is an outlier in Kurosawa's filmography in that it's typically dismissed by critics as a lesser work from the master's early era. This dismissal comes with an asterisk, however, as the version available to the public — it is currently on The Criterion Channel — is not complete. The cut Kurosawa submitted to Shochiku, the studio distributing it, was intended to be released in two parts and have a total running time of 265 minutes. The studio, without consulting Kurosawa, ended up cutting a full 99 minutes out of the film, and releasing the extremely truncated version to the director's umbrage.

"In that case," Kurosawa is heard to have said, "better to cut it lengthwise."

Despite Kurosawa immediately attempting to find and restore the missing footage, it remains missing to this day. The shortened film that audiences did see was not a critical success, and to this day, critics notice how difficult the narrative is to grasp, and how characters seem inconsistent. Esquire was particularly hard in its 1963 review, calling "The Idiot" amateurish and lacking Kurosawa's usual virtuosity. The only place "The Idiot" found fans was in Russia; It's been reported that Andrei Tarkovsky was a fan.

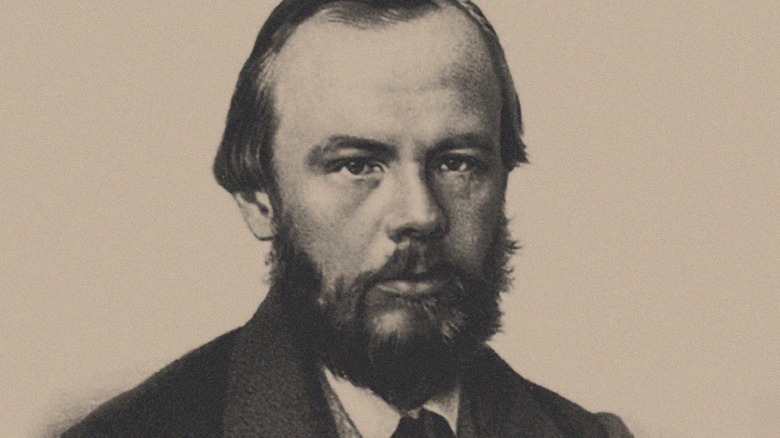

Dostoyevsky

Kurosawa's "The Idiot" is one of many film and TV versions of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's 1868 novel, first published in chapters in The Russian Messenger. The first film version of "The Idiot" was Carl Forelich's 1921 German film "Wandering Souls," followed a George Lampin film, "L'Idiot," in 1946. Kurosawa's was the third.

The original novel was written under some pretty harrowing circumstances. Dostoyevsky was on the lam in Switzerland and Italy to avoid Russian creditors, and was living in extreme poverty. Dostoyevsky and his wife, Anna Grigoryevna, moved multiple times during the writing of "The Idiot," caught in a spiral of debt thanks largely to Dostoyevsky's gambling addiction and epilepsy. It was also during this time that the couple would have a daughter, Sofia, who died only three months after she was born. Faced with personal tragedy, illness, addiction, and the never-ending pursuit of debt-collectors, Dostoyesky wrote what might be called a semi-autobiographical novel of peace, gentleness, and the triumph of optimism.

"The Idiot" is about a Candide-like character named Prince Myshkin who moves in with relatives St. Petersberg, the city where he can seek treatment for his epilepsy, but also his "idiocy." Myshkin is a peaceful, detached, naïve character who seems peacefully unfazed by much of the drama around him, leading people to believe he is feeble-minded. Much of the novel's drama centers of Myshkin's family and his own financial situation, but comes alive during the philosophical discussions has between Myshkin — who is attempting to live life by a pure, gentle Christian doctrine centered on the harmonious unity of being — and a character named Ippolit who lives by an atheist doctrine, and believes that all our yesterdays have lighted fools the way to dusty death. As in Dostoyevsky's most notable works, each character stands as a symbolic exemplar of a particular philosophy, and their conversations serve simultaneously as drama and as Platonic dialogue.

Please read Dostoyevsky. He's rad.

The Kurosawa version

Kurosawa was very fond of Dostoyevsky's novel, as Kurosawa also adhered to a generally optimistic view of humanity, frequently arguing that helping others and living gently and resolutely is preferable to cynicism and fear. Looking over Kurosawa's filmography, one might find a long interplay between hope about humanity and bitterness in its flaws. At his most optimistic, he makes "Ikiru." At his most cynical, he makes "Yojimbo." While both Dostoyesky and Kurosawa were capable of unrelenting bleakness, neither could be called unrelentingly bleak artists. Even as violence surrounds Myshkin — named Kameda in Kurosawa's version — the point of the character is they choose to see the world as being a place where hope is possible. That things end badly for Myshkin/Kameda is not so much a failure of their own hope, but a testament to a bleak world that has not yet outgrown its own addiction to misery.

The action of Kurosawa's film is updated to the 1940s, and the setting is transposed to the city Sapporo on Hokkaido, the north island of Japan — hardly the bustling metropolis of St. Petersberg. In opening dialogue, Kurosawa lays out his themes plainly: "Dostoyevsky wanted to portray a genuinely good man," it said. "It may seem ironic, choosing a young idiot as his hero, but in this world, goodness and idiocy are often equated. The story tells of the destruction of a pure soul by a faithless world."

The hopefulness in Kurosawa's film comes not from Christian doctrine, nor is it even religious in origin, really. Kurosawa's Kameda is more secularly philosophical, living by the practical, immediate gentleness of his soul, rather than by the example of any God or holy figure. Indeed, Kameda even says out loud that he doesn't particularly believe in God. The scene in which Kameda says this is to the literally deaf ear of an older woman siting next to a Shinto shrine. The Divine, Kurosawa is arguing, is not going to provide modern Japan with the solutions it needs to be kind and gentle. Kurosawa's "The Idiot" is openly humanist.

That the film is set in Sapporo and not a bigger, more cinematically recognizable city, is surely meant to show a smaller, quieter, snow-blanketed Japan of the past, perhaps embellished by nostalgia, but nonetheless capturing a portrait of a lost, better time.

The complete version

Despite some thematic heft and a sprinkle of theology, "The Idiot" is still seen as one of Kurosawa's lesser works. The drastic cuts made to "The Idiot" seem to have robbed the story of some much-needed narrative clarity, leaving the events of the film unclear and difficult to track. The film moves very inorganically from scene to scene, and big discussions don't lend well to the thematic pacing. This was, of course, after the full 99 minutes of missing footage was removed. For context, that's about the length of "WALL-E."

In 1991, Kurosawa would make another film for Shochiku, "Rhapsody in August," and, during production, searched the Shochiku archive for any of his old missing footage from 40 years before. This process was detailed in the 1999 documentary film "Kurosawa: The Last Emperor" directed by Alex Cox (yes, the Alex Cox who made "Repo Man" and "Sid & Nancy"). According to Cox and to Kurosawa, the footage was nowhere to be found, meaning the complete cut envisioned by Kurosawa is lost.

Forever? Perhaps. But stranger things have happened. Much of "Metropolis" was reconstructed, and "The Other Side of the Wind" was eventually completed.

We have reasons to be hopeful.