The Matrix Resurrections Spoiler Review: Plenty Of Déjà Vu In A Sequel That's Glitchy But Game

"What is the Matrix?" The question that once drove Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves) mad has led him and us — "inexorably," as the system's Architect would say — to a fourth installment in the franchise, "The Matrix Resurrections." It's the very definition of a legacy sequel, in that it comes further along in the series timeline and commingles new characters with beloved old ones.

It's been 18 years since the last "Matrix" movie, so there is now a whole generation of filmgoers who were born and have grown to graduation age during the franchise's absence from the big screen. For the class of '99, the first "Matrix" was the cultural event that "Star Wars: The Phantom Menace" was supposed to be. It had big mythic ideas, wrapped in a blockbuster package. They came flying at the viewer in bullet time.

A lot has happened since then. The sibling directorial duo of the Wachowskis have both gender transitioned, and only one of them, Lana Wachowski, is back this time. Gone, too, are actors Laurence Fishburne and Hugo Weaving, both of whom played integral parts in the original "Matrix" trilogy.

What's left are Reeves and Carrie-Anne Moss as Neo and Trinity, along with a kind of guilty meta conscience. "The Matrix Resurrections" knows what it's getting into when it tumbles down that white rabbit hole of memories, all those flashes of old footage and reenacted scenes. Trinity once sent Mr. Anderson a message saying, "Wake up, Neo," but now she herself is asleep as "Tiffany," and the tentpole circuit has degenerated into a Force-Awakened landscape of remixes that prize nostalgia and rhymes over reinvention.

Is knowing — and showing its awareness of — remix cliches enough to set "The Matrix Resurrections" apart from the franchise pack? Let's talk about that ... with spoilers.

Lines of Code

"The Matrix Resurrections" essentially begins and ends the same way as "The Matrix." Along the way, it shows us familiar images and recycles dialogue with a wink. Like its newfangled machine pets, the movie does veer off in different exploratory directions, but it also keeps circling back to 1999 signposts, as if it's on a long leash but can only operate within a certain set of parameters. That may very well be the conditions under which Wachowski made the film for Warner Bros.

"Resurrections" opens with a blinking cursor and talk of "old code" that "feels familiar" and "feels like a trap." This comes across like its own not-so-subtle code language from Wachowski and her co-writers, David Mitchell and Aleksander Hemon. It's not the only example of that we hear as the movie puts us back in the middle of a police raid on the old Heart o' the City Hotel, where a Trinity lookalike sits in front of the computer again.

This time, the cops wear SWAT gear instead of uniforms, Morpheus is somehow an agent with the face of Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, and there are two new observers and audience surrogates who watch it all play out from a side room and deliver their own running commentary. To go further with the machine metaphor, "Resurrections" is self-aware and it's aware that you are aware as it harvests you, but rather than repress that awareness, it force-feeds you the eye-opening red pill: pointing out the mechanics of what it is doing, showing you the green lines of code in itself.

"We know this story," says Bug, the former window washer with blue hair and an unlocked mind, played by Jessica Henwick (who makes for a strong addition to the cast). "This is how it all began." But "maybe this isn't the story we think it is."

Enter the Modal

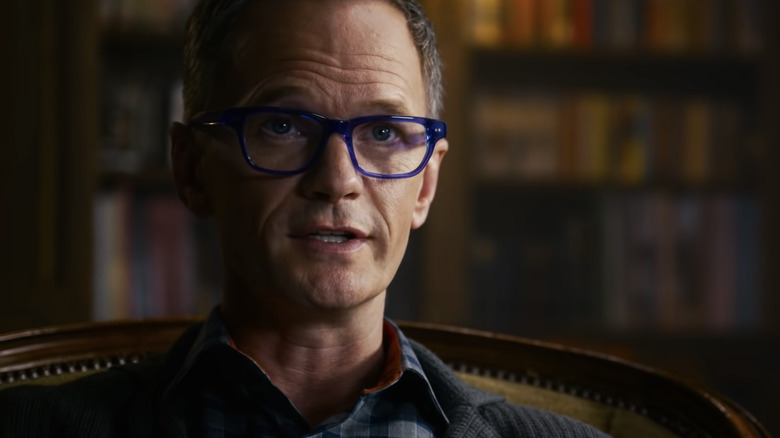

Through Bug, we learn that old "Matrix" scenes are playing out in a modal, a "simulation to evolve programs." Neo himself created this modal in his capacity as the world's greatest video game designer. His new "Matrix" identity is a step up from his old one, though our monologuing villain, the Analyst (Neil Patrick Harris), has him doped up on prescription blue pills and doubting his sanity while he pines after Trinity in a coffee shop.

The video game element adds another meta layer to the proceedings, since "The Matrix" trilogy now exists in-universe as games. There are about 20 or 30 times where Wachowski goes "The Godfather Part III" route and splices in footage from previous films. She also name-drops Warner Bros. outright as Neo's parent company and effectively lets us know they were going to do this sequel with or without her.

Bug seems worthy of her own spin-off, but "The Matrix" series has a tendency to overextend itself, character-wise, and that continues in "Resurrections." Some new supporting characters, like Neo's chummy tag-along coworker, Jude (Andrew Caldwell), are intentionally annoying, while others just take up the screen without manifesting much personality or reason for their existence.

This is part of where the first two back-to-back sequels went astray. That being said, Jonathan Groff nails Weaving's vocal patterns when he needs to and is a delight as the new Smith, who still clings to Neo like a virus in the form of a business partner.

The movie shows how the machines resurrected Neo, but to the best of my recollection from two theater screenings, it's never explained in "Resurrections" how Smith came back to life. The viewer is just left to infer that it might have something to do with Smith's old "connection" to Neo. In "The Matrix Reloaded," Smith himself doesn't understand that connection and can only speculate, "Perhaps some part of you imprinted onto me, something overwritten or copied."

Music, Action, and Sound

"The Matrix Resurrections" reunites Wachowski and Mitchell, the author of "Cloud Atlas," with Tom Tykwer, co-director of the film adaptation. Here, Tykwer and Johnny Klimek are on music duty. Though composer Don Davis left them with some big shoes to fill, they've done an admirable job. Their soundtrack gives "Resurrections" a sweeping momentum and even a majesty at points, like when Neo steps through the door of white light onto the bullet train with Bug.

The structuring of a montage around Jefferson Airplane's "White Rabbit" feels less inspired, but maybe that's the point, since the montage is lampooning the process of a studio sequel made by committee. David Fincher utilized the same song in his pre-"Matrix" film, "The Game," which also toyed with the idea of the falsity or unreality of surface reality. In "Resurrections," Neo even tries to jump off a building like Michael Douglas in that film.

The action in "Resurrections" is nothing to write home about. It lacks the tension of the fights against the invincible Agent Smith in "The Matrix," and there's none of the kinetic energy of the chateau fight or the freeway chase in "The Matrix Reloaded," either.

There are also a few points where I found myself really relating to Ben Pearson's recent video essay for /Film on why movie dialogue has gotten more difficult to understand. Whether it be Bugs offering pills in a breathless manner, or the returning exiled program, the Merovingian (Thomas Lambert), raving on the sidelines of a fight, I had a hard time parsing what characters were saying sometimes. Since HBO Max isn't on offer where I live, I didn't have the benefit of subtitles, but even some of the clips that are available online have stray lines that I can't make out easily.

The Modal Morpheus

Together with Smith, the other major legacy character who has been recast for "The Matrix Resurrections" is Morpheus. As much as I like Abdul-Mateen, I can't be the only audience member or lookie-loo Redditor who still wonders why Fishburne wasn't asked to return. Maybe it's not such a mystery, though, since it becomes all too clear in "Resurrections" that Wachowski, like certain pragmatic residents of old Zion, no longer takes Morpheus all that seriously.

Abdul-Mateen delivers a more irreverent take on the character, who gets drunk on red pills and playfully parodies the portentousness of his predecessor — the "lightning, thunder, and theater," as he calls it. In keeping with the movie's brighter color palette, his fashion has become more ostentatious, and he knows enough about movies and making a good first impression to break the ice with a callback (and then call out the callback. Because meta.)

Fishburne's Morpheus was a staunch believer in the Prophecy of the One, but as the sequels deconstructed that narrative, it left Morpheus adrift, even perhaps spent, like he no longer had a purpose as a character. The Wachowskis even let the canonical "Matrix Online" video game kill Morpheus off, but now, as Lana goes about resurrecting other characters, she doesn't quite know what to do with old Morph.

So we get the modal Morpheus, who mashes up characteristics of Smith and Morpheus into "a combo pack of counter-programming, algorithmic reflections of forces who helped" Neo become Neo. The uncharitable view would be to say that this is a fancy way of reducing Morpheus to Neo's jokey digital helper. As the movie spills over into the world outside the Matrix, Morpheus somewhat fades to the background, though he's still capable of manifesting himself in the city of Io through an "exomorphic particle codex" with "paramagnetic oscillation."

The Great Battery Heist

If it sounds like I'm being hard on "The Matrix Resurrections" or hyper-critical of it, let me just stress that I did enjoy it and find it entertaining, for the most part. The best compliment I can pay it would be to say that it reignited my interest in the "Matrix" mythos enough that it made me do a full rewatch of the original trilogy afterward. Three years ago, when I defended "The Matrix Reloaded," I couldn't bring myself to watch "Revolutions" again, even though "Reloaded" leads into it with a cliffhanger.

The machine is running smoother in "Resurrections," but that comes with some reservations. While serviceable, it feels like this sequel goes too light and fluffy romantic, abandoning philosophy and degenerating into a simple exercise in mythology-driven fan service toward the end. "The Matrix" means different things to different people, but for me, its defining feature — the thing that made it so compelling — was never the love story between two fictional characters.

Trinity is sidelined until the third act, at which point "Resurrections" becomes a heist movie (which I guess makes it "Inception?"), complete with characters standing around explaining the plan, in a scene intercut with flash forwards of them carrying out the plan. In this case, they're just planning to heist a human from the place where humans are siphoned as living Duracell batteries.

There's a moment in that scene where the modal Morpheus says, "The exomorph slinkies up Neo's old umbilicus," and it took me right back to "The Force Awakens," when they were standing around in a similar manner, talking about "thermal oscillators." It turns out Priyanka Chopra's bespectacled character is Sati, the little girl from the train platform in "The Matrix Revolutions," all grown up. She does her best to guide us through the pedestrian plot maneuvers, but even as Neo comes down from his "Rapunzel tower," it feels like they've left Trinity stuck up in one.

Paint the Sky with Rainbows

I won't try to laundry-list every single concept or image that "Resurrections" repeats from "The Matrix" trilogy, but there are enough of them that it starts to feel like the movie has a limited range of ideas and a limited visual vocabulary. If I were grasping for themes, however, I'd say it's not completely bereft of subtext. For trans people in particular, this movie might have something worthwhile to say about the human experience.

When the game designers are throwing out ideas for what "The Matrix" is about, there are some off-the-wall ones like "crypto-fascism," but one of them also says, "trans politics." Last year, Lilly Wachowski acknowledged in a Netflix Film Club video that "The Matrix" was originally intended as a trans allegory, but "the corporate world wasn't ready for it." The bleached-blonde character of Switch (Belinda McClory), for instance, was first conceived as a man in the real world and a woman in the Matrix.

Given Lana Wachowski's own transitioning and the presence of other signifiers (like a game named "Binary"), perhaps it's no coincidence that the power transitions from Neo to Trinity in "The Matrix Resurrections." In "The Matrix Reloaded," Neo had to choose between two doors, one of which would lead to Trinity and enable him to save her (by massaging her heart back to life), but which might spell doom for the rest of the human race.

"Resurrections" passes the agency for such fateful decisions to Trinity. "This time, the most important choice in Neo's life is not his to make," someone says. If Trinity decides to take the blue pill and stay in the Matrix, Neo will, too. Fortunately, she goes the other way, taking flight and knocking the misogynistic Analyst's jaw off, ready to remake his world and "paint the sky with rainbows." (You can see one in the clouds at the end).

One of the Ones

In "The Matrix," the Wachowskis made audiences believe in the One, but we know from the sequels that they don't really believe in the One, and in "Resurrections," both Neo and Niobe (a returning Jada Pinkett Smith in old-age makeup) reiterate that sentiment, saying they never believed, either. Neo is just one in a cycle of Ones, but with his personal and specific attachment to Trinity — recapitulated, now, across this personal and specific four-quel — he did break the mold. And Niobe reassures us that his hero's journey and sacrifice in the trilogy still mattered because they shattered the "us versus them" dichotomy and gave humans and their machine allies a "world without war," not to mention a world with fresh-grown strawberries.

Be that as it may, Neo's powers aren't what they used to be. He mostly just throws up force fields and does his glowy new "mojo rising" move. It's a funny moment when someone says, "I don't suppose you can still fly," and Neo tries to take off from the ground, only to give up and say, "Yeah, that's not happening."

That's rather emblematic of "The Matrix Resurrections" as a whole. My main issue with "Resurrections" is that it's not enough to point out cinema crimes but then still keep perpetrating them. This is a movie that shows us people on treadmills and talks of trivialized stories and how "we're all trapped inside these strange repeating loops." It self-consciously speaks of not being a retread or regurgitation yet much of what's onscreen is regurgitated.

Tony Soprano once said, "'Remember when' is the lowest form of conversation." Yet even his franchise indulged in a bit of "remember when" this year with "The Many Saints of Newark." Now, we have Neo here in a hovercraft called Mnemosyne, saying, "I remember this," and, "I don't remember this," while Trinity says, "I remember us," and we're all encouraged to remember. "Nothing comforts [cultural] anxiety like a little nostalgia."

The Hollywood Matrix and Fandom Matrix

Another relevant quote here might be one from Morpheus himself, who once told Neo, "There's a difference between knowing the path and walking the path." "The Matrix Resurrections" knows the well-trodden path of legacy sequels and walks it with its own idiosyncratic style, but I guess my inner Morpheus as a movie-lover was hoping it would be the One to finally rise above that path (which as it turns out, may just be a hamster wheel).

As it is, "Resurrections" is a solid rebound from "Revolutions" that is neither revolutionary nor revelatory. Wachowski herself has shot down the idea of a new trilogy, though it wouldn't surprise me if Warner Bros. took the ball from here and gave us a "Matrix Revelations" or a "Matrix Retconned" or a "Matrix Reboots" in the future. This one already feels like "The Matrix Remixed," meta-parody style.

When Trinity and Neo do their Superwoman and Superman thang at the end, it's a reminder that superhero fatigue and nostalgia fatigue don't really exist. At a time when so many long-running film franchises feel like they're doing cover-song versions of themselves, "The Matrix Resurrections" elects to go the way of a literal cover song as an outro. It's a new rendition of the very song that ended "The Matrix," Rage Against the Machine's "Wake Up," this time performed by Brass Against. The vocals that Zack de la Rocha once spewed like molten lava have been replaced by those of a different artist, Sophia Urista.

I like the cover, but it is a cover, and hearing it in the context of the same fly-away ending left me with the nagging feeling that the movie was trapped inside the Hollywood matrix, while all of us are trapped inside the fandom matrix: running around, looking for phone booths that don't exist anymore in a system that has cut off all modes of escape.