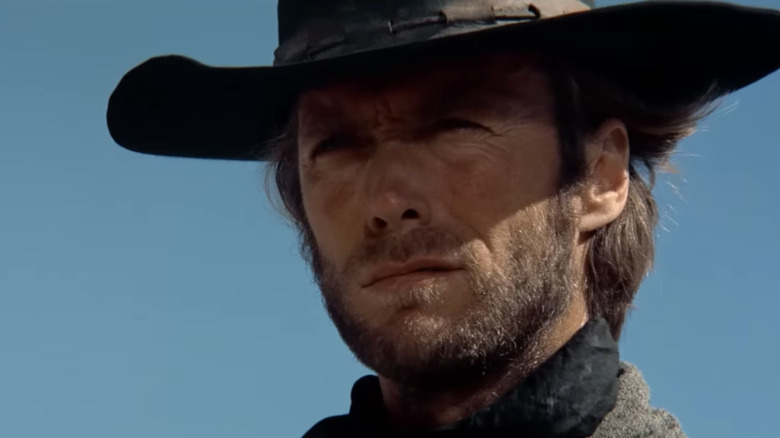

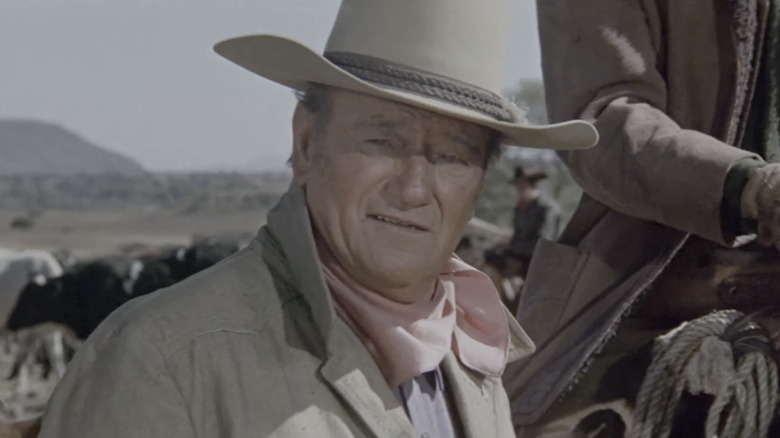

Clint Eastwood And John Wayne's Feud, Explained

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Movie stars don't get much bigger than Clint Eastwood and John Wayne. Both belong to an age where movie stars were more than just popular actors who could reliably sell tickets. The Duke in particular represented the human embodiment of an ideology. He was more than just an avatar for conservative ideals, he was in many ways the face of a monoculture that simply doesn't exist any more; a symbol of a society organized around shared ideals which disintegrated as the century wore on. Eastwood rose to fame in the '70s, where culture was much more fractured than it had been in Wayne's heyday. But he was about as close as you could get to what his forbear represented in the first half of the 20th Century, especially when it came to the Western genre.

Both Eastwood and the Duke cut their teeth on Oaters, establishing their enduring star power by way of horseback battles and a stoic machismo that ensured they became emblems of masculinity for entire generations. While an on-screen meeting between the two seemed like a foregone conclusion, then, these two Western titans actually never came face-to-face in any film.

Most of that came down to the fact that Wayne simply wasn't a fan of Eastwood's more cynical, deconstructionist Westerns. It was this that led to a rift between the pair that lasted until the Duke's passing in 1979. Eastwood had some clashes in his time (his feud with Spike Lee got so bad Steven Spielberg had to step in). But his issues with Wayne represented something much deeper — a clash of generations. Here's everything you need to know about the feud between Wayne and Eastwood and why we never saw these legends star opposite one another.

John Wayne and Clint Eastwood represented two very different Western styles

Before he became a screen legend John Wayne was just a young college student and football player who helped out with props on movie sets. It was during these early years that he met director John Ford who he literally knocked over during their first encounter and who would eventually cast Wayne in his seminal 1939 Western "Stagecoach." While there was a subversive element to the film, which undermined many of the well-established tropes of the genre by revealing its archetypal characters as more layered and complex individuals, it was still very much of a pre-revisionist age — an age for which Wayne himself became emblematic.

Throughout the next three decades, the Duke became a symbol of simplistic good vs. evil Western storytelling. He wasn't just starring in Oaters, but they were his bread and butter and he remains synonymous with the Western genre to this day. The same is somewhat true of Clint Eastwood, who similarly made his name by playing cowboys and outlaws. But the movies Eastwood was making were very different to those top-lined by his predecessor.

His role as Rowdy Yates in CBS' 1960s series "Rawhide" made him a TV star, and was the closest Eastwood came to portraying the same morally straightforward characters inhabited by Wayne. By the time he played the Man with No Name in Sergio Leone's celebrated "Dollars" trilogy, however, he was embracing a much more complex anti-heroic ethos which came to define his Western output over the next few decades — culminating in 1992 with what is arguably the quintessential revisionist Western, "Unforgiven." Though Wayne wasn't around for that early-'90s triumph, he was around to witness Eastwood's rise as a pioneer of the revisionist Western, and he wasn't a fan.

John Wayne was disgusted by Clint Eastwood's High Plains Drifter

After Clint Eastwood made the jump from TV to the big screen with 1964's "A Fistful of Dollars" he started to become the face of a genre undergoing a dramatic shift. Westerns traditionally embraced a straightforward good guys vs. bad guys ethos, and John Wayne was at the forefront of it. Eastwood's Western protagonists were much more morally questionable and that was particularly true of 1973's "High Plains Drifter."

By this point, Eastwood had starred in Don Siegel's celebrated (and controversial) 1971 crime thriller "Dirty Harry." With "High Plains Drifter" (which hit Netflix in 2025) the actor once again played a morally questionable hero in the form of The Stranger, a mysterious figure who arrives in the Old West town of Lago and metes out his own merciless form of justice. The movie was an early directorial effort from Eastwood, who infused the film with the same revisionist ethos that had characterized his Sergio Leone collaborations, but turned everything up to 10, deconstructing the cowboy archetype that Wayne had been so pivotal in establishing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, Wayne wrote Eastwood an angry letter over "High Plains Drifter" in which he chastised the young actor for what he claimed was an inaccurate portrayal of the American West. In a 1992 Los Angeles Times interview, Eastwood recalled Wayne writing, "That isn't what the West was all about. That isn't the American people who settled who settled this country." The actor reflected on receiving the Duke's missive, saying "I realized that there's two different generations, and he wouldn't understand what I was doing. 'High Plains Drifter' was meant to be a fable: it wasn't meant to show the hours of pioneering drudgery. It wasn't supposed to be anything about settling the West."

John Wayne turned down the offer to star opposite Clint Eastwood

The 1970s were a fascinating time for the Western, beginning with controversial acid Western "El Topo" and ending with the hopeless Arnold Schwarzenegger-led Western flop "The Villain." During this transformative decade, Clint Eastwood not only established himself as a star, he established the revisionist Western as the de facto form of the genre.

It's no wonder, then, that John Wayne refused to join Eastwood in what would have been a thrilling team-up. Along with Bob Barbash, writer/director Larry Cohen co-wrote a script for the duo entitled "The Hostiles," which would have seen Eastwood play a gambler who wins half a ranch. The other half was owned by an old gunslinger, who would have been portrayed by Wayne. Unfortunately, as Cohen told author Michael Doyle, writer of "Larry Cohen: The Stuff of Gods and Monsters," Wayne recoiled when offered the chance to star opposite Eastwood in the feature. Such a film would have represented Wayne officially anointing the young star as his successor, but the Duke simply wasn't interested.

A last ditch attempt on Cohen's part involved sending his screenplay to Wayne's son, Michael, who handed it to his father during a fishing trip. As the screenwriter recalled:

"The following week, I got Michael on the phone and asked him what had happened. He said, 'Well, Dad was sitting on the boat and I handed him the script. He looked at it for a few minutes and then said, 'This piece of s*** again!' And then he threw it overboard.' I quietly thought to myself, 'Oh, there goes my beautiful script, slowly sinking beneath the blue Pacific along with the hopes and dreams of Clint Eastwood and Bob Barbash!'"

John Wayne likely felt threatened by Clint Eastwood

As "John Wayne: The Life and Legend" author Scott Eyman wrote, "[Wayne] was sensitive about the drift toward nihilism and probably felt a little threatened." By the 1970s Wayne's time was coming to an end and he surely felt the tectonic cultural shift that turned his simplistic Western formula into a relic. He'd also fought cancer and even had a lung removed, not to mention the fact he was one of many actors who'd damaged their bodies forever, pushing through immense pain to make many of his 1970s films.

That would be enough to make the screen legend wary of this youngster, Clint Eastwood. But Wayne also kicked off the '70s by turning down the lead role in "Dirty Harry," a decision he late lamented. In Michael Munn's book "John Wayne: The Man Behind The Myth," the star is quoted as saying, "I thought Harry was a rogue cop. I saw the picture, and I realized that Harry was the kind of part I'd played often enough — a guy who lives within the law but breaks the rules when he really has to in order to save others."

When Wayne worked with Don Siegel on 1976's "The Shootist," the "Dirty Harry" director made a major error when he told Wayne to shoot a villain in the back because it's what Clint Eastwood would do. As Eastwood recalled on an episode of Inside the Actors Studio, "Wayne turned blue and he said, 'I don't care what that kid would have done, I don't shoot him in the back.'" Interestingly enough, Eastwood ended up visiting the set of "The Shootist," marking it as not only Wayne's final on-screen performance but the one and only time the two titans of the Western genre ever met.