15 Horror Movies Without Jump Scares That Still Terrify Audiences

In both humans and animals, the startle response is an evolutionary adaptation, an unconscious response to stimuli as a means of survival. If a scary animal or a suspicious person suddenly appears in front of us, we might scream or jump instinctively. Strangely enough, we may have the same response if we see something startling on a TV show or in a film. At some point, filmmakers learned that they could elicit this biological response through clever editing, blocking, and other filmmaking tools, and they have been making us jump out of our skin ever since.

To be sure, a certain amount of pleasure can be found in being scared like this, as many horror movie fans can tell you. Being physically or emotionally affected by a film can be a thrill. But not everyone enjoys the feeling of being startled, and not all jump scares are created equal. Some feel cheap, like taking the easy route to scare audiences. Thankfully, horror movies don't need jump scares to frighten us. If you're tired of these horror movie tricks or never liked them to begin with, here are 15 films without any jump scares that still terrify audiences.

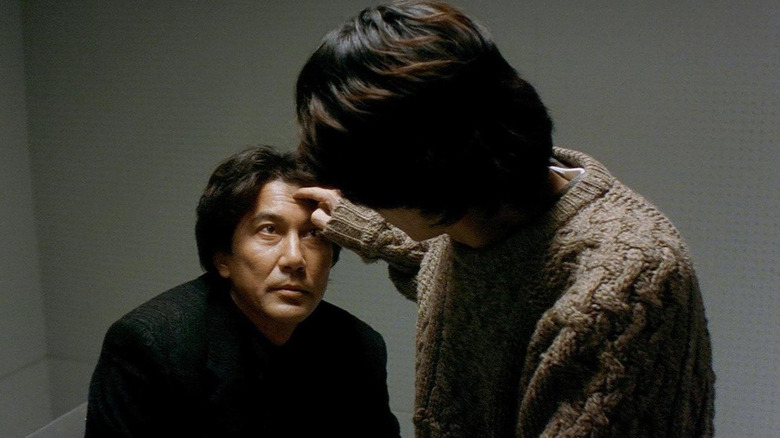

Cure

Japanese director Kiyoshi Kurosawa is a master of developing a sinking sense of dread in his films. We see this in "Pulse," perhaps the most harrowing movie about loneliness ever made. But Kurosawa's 1997 film "Cure" inspires this dread from the very beginning, and that unsettling feeling never lets up. We follow Kenichi Takabe (Kōji Yakusho), a Tokyo detective investigating a series of perplexing murders. Though each killing was perpetrated by a different person, the crimes bear striking similarities: The victims have a large "X" carved into them, and the killers are easily caught nearby.

As Takabe searches for connections between the crimes, he begins to suspect that some sort of psychic malevolence is at play. "Cure" at times feels spiritually connected to David Fincher's "Se7en," though the central mystery becomes even less clear as Takabe furthers his investigation. Philosophical, psychological, and certainly atmospheric, the film unsettles the viewer by denying us the explanations we seek. The terror lies not in the existence of monsters or killers but in the fact that we may not be able to trust our own minds.

The Exorcist

Modern horror wouldn't exist without "The Exorcist" or its director, William Friedkin. Considered one of the scariest films ever made, especially at the time of its release, "The Exorcist" is a classic that still holds up today. The film centers on a 12-year-old girl named Regan (Linda Blair), who begins behaving strangely. She speaks in tongues and even levitates off her bed. Her mother, Chris (Ellen Burstyn), is at a loss and turns to Father Karras (Jason Miller), a priest experiencing a crisis of faith.

The exorcism story is a tale as old as time, but Friedkin's film remains the gold standard. "The Exorcist" is a slow-burn, getting to know the characters and their psychic pain alongside the supernatural conundrum at its center. While there are some sudden loud noises and certainly a few startling moments, Regan's jarring, unnatural behavior disturbs viewers more than anything. Regardless of your religious affiliation, you can't deny that something is very wrong here.

Rosemary's Baby

We often assume that horror movies from many decades ago aren't as scary as contemporary films, and in some cases, that's true. But if you've seen the seminal, controversial classic "Rosemary's Baby," you know there are exceptions to the rule. Roman Polanski's film stars Mia Farrow as Rosemary, a young woman pregnant with her first child. Rosemary moves into a New York City apartment with her husband, Guy (John Cassavetes), and begins to suspect something is amiss with her neighbors, who behave strangely toward her unborn child.

"Rosemary's Baby" doesn't use flashy horror techniques like jump scares to frighten the viewer. In fact, we never actually see the titular baby, even though so much is made of his supernatural importance. Instead, the film traffics in paranoia, as we follow Rosemary's descent into suspicion and eventually madness. There are no monsters (that we can see, at least) nor much violence, though the latter aspect is heavily implied. The film suggests, rather than declares, that something is off, making it a very scary movie indeed.

The Silence of the Lambs

The only horror film to win Best Picture at the Oscars, Jonathan Demme's "The Silence of the Lambs" proves that less is more. Like the Thomas Harris novels on which the film is based, "The Silence of the Lambs" hinges on the complex, perverse relationship between cannibal serial killer Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) and FBI trainee Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster). Clarice and her team are hunting "Buffalo Bill" (Ted Levine), a serial killer who skins his victims. Clarice, an attractive young woman, is sent to interview the imprisoned Lecter to gain insight about this case.

Though Lecter's (and Buffalo Bill's) crimes are viscerally disturbing, it's not violence that makes the film so terrifying. Even within a cage, Lecter's leering demeanor gives you the shivers. We don't need to see the violence he's capable of to know how dangerous it is. That's not to say "The Silence of the Lambs" is without violence. In one harrowing scene, Lecter attacks the guards and escapes by wearing one of their faces, and Clarice's lights-out showdown with Buffalo Bill is a total thrill. But the scariest violence remains hidden within.

Sea Fever

It's a shame that the sci-fi horror movie "Sea Fever" came out in April of 2020, as it meant that not many people watched it. At the same time, "Sea Fever" coming out at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic is oddly fitting, considering the film's infectious premise. Hermione Corfield plays Siobhán, a PhD student in marine biology, who boards an Irish fishing boat to study deep-sea marine life. Far out at sea, the crew encounters a mysterious sea creature that stops their boat in its tracks. As members of the crew begin behaving strangely and falling ill, Siobhán comes to an unsettling realization about the cause.

"Sea Fever" draws inspiration from horror classic "The Thing," transposing that frozen story to the deep sea. As in John Carpenter's classic, much of the thrill comes from the paranoia the monster stokes. Moreover, like the best creature films, "Sea Fever" holds back on showing the creature too much, letting the suspense do the talking.

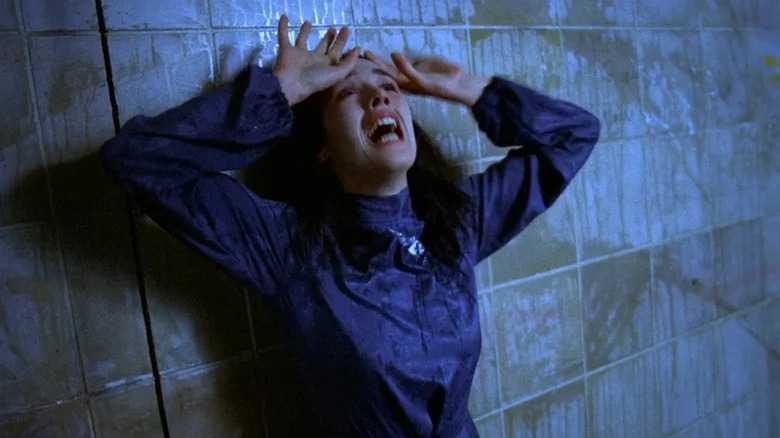

Possession

Arguably the most disturbing film about marriage ever made, Andrzej Żuławski's "Possession" defies reason. Sam Neill plays Mark, a spy who returns home to West Berlin to find his wife, Anna (Isabelle Adjani), behaving strangely. Anna asks for a divorce but won't tell Mark why, and when Mark becomes worried for the well-being of their son, he endeavors to find out what's going on with his wife. What he finds is worse — and weirder — than he could have ever imagined, and it involves a doppelgänger, a Lovecraftian alien, and a truly bizarre breakdown in the subway.

You've never seen anything like the cult classic "Possession," which is why it's not surprising that it doesn't rely on one of the most straightforward horror techniques — the jump scare. Instead, Żuławski's controversial movie communicates a sense of uncanny abjection. Both Mark and Anna's behavior becomes increasingly erratic, and their lack of connection to reality or reason promotes the feeling of startling unease that permeates the film.

The Vanishing

Stanley Kubrick once called "The Vanishing" the scariest film he had ever seen, which gives you an indication of how cleverly director George Sluizer tells this eerie story. We open with Rex (Gene Bervoets) and Saskia (Johanna ter Steege), a young Dutch couple vacationing in France. Their idyllic trip turns into a nightmare when Saskia disappears without a trace in broad daylight. Rex spends years obsessing over Saskia's disappearance, until he runs into Raymond (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), a deceptively normal man who knows more than he lets on.

"The Vanishing" toys with the audience, seemingly telling us the answers we seek while taking us down a dark path of madness. The film's inventive structure bucks tradition, avoiding horror tropes fans of the genre might expect. Flashing back between the present and the past, "The Vanishing" develops a building sense of unease until its showstopping finale, often considered one of the most terrifying endings of all time. The journey to get there is just as impressive as the result, and it will leave you wondering how Sluizer so smoothly led you through his disturbing maze.

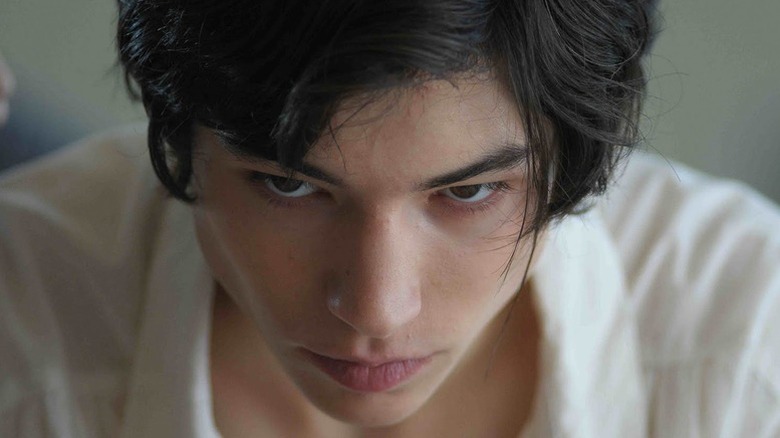

We Need To Talk About Kevin

Lynne Ramsay's film "We Need to Talk About Kevin" depicts a parent's worst nightmare. What if your child grows up to be a sociopath? What if you hate your child, and the feeling is mutual? Tilda Swinton plays Eva, the parent in question. She gives up her life of adventure to have a child with her husband, Franklin (John C. Reilly) and comes to regret this decision more with every passing year. Eva and Franklin's son, Kevin, is a difficult child who grows into a terrifying teenager (Ezra Miller). When Kevin commits a heinous act, Eva struggles with the guilt she feels about his behavior.

Though Kevin is a violent child, "We Need to Talk About Kevin" is not a violent film, at least not explicitly. The climactic act of violence is not horrifying simply by virtue of the pain it inflicts on others, but because of how it illustrates Kevin's lack of humanity. We feel for Eva because she had the bad luck to be saddled with this horrible child, though everyone around her must assume her lack of nurturing is partially to blame. One of the most disturbing films about motherhood ever made, the hideousness of "We Need to Talk About Kevin" gets under your skin without making you jump.

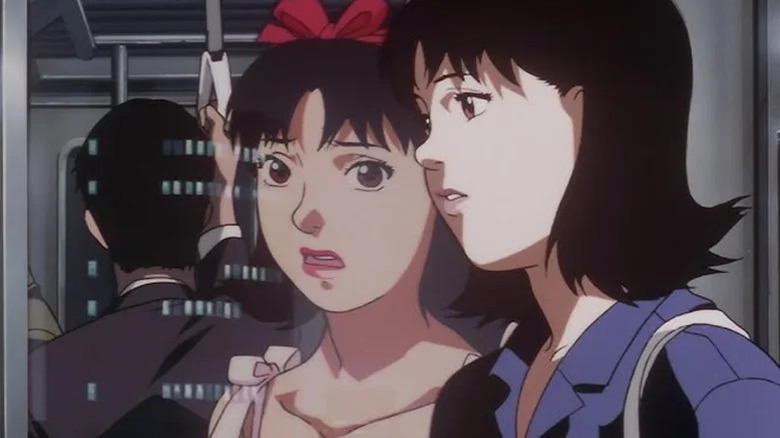

Perfect Blue

Often considered one of the best animated films ever made, Satoshi Kon's "Perfect Blue" reminds viewers of the power of the medium. The film follows Mima (Junko Iwao), a pop singer who leaves her girl group to pursue an acting career. She gets a job on a murder mystery show called "Double Bind," and her life starts to unravel from there. An obsessive fan begins stalking her, upset with Mima for changing her image. A website documents her every move, and people around her start winding up dead.

Though "Perfect Blue" depicts the kind of violence one might expect from a horror film (in fact, it draws from the famously bloody Italian film genre of giallo), psychological terror drives the film's most horrific moments, so no jump scares are needed. It's no wonder "Perfect Blue" inspired Darren Aronofsky to make "Black Swan," as both films play with the fracturing of reality and identity to great effect. Kon's masterpiece will surely disabuse viewers of the notion that animated films aren't as impactful as their live-action counterparts.

The Blair Witch Project

Whether you like the film or not, it's an inarguable fact that "The Blair Witch Project" changed horror forever. The most influential found footage horror film ever made, the movie gained renown in part because of its brilliant marketing campaign, which convinced some viewers that the events of the film really happened. Marketing aside, "The Blair Witch Project" is a very scary film (even Stephen King couldn't finish it) that doesn't use jump scares to frighten the viewer. Indeed, the movie succeeds in scaring us so much because of what it doesn't show.

For one, we never actually see the titular Blair Witch, nor do we know what she looks like. Her lack of physical presence means that she could always be around the corner, or just out of frame. The faux-documentary style of the movie limits our view of the situation, and we can only see what our protagonists capture on camera. We witness their terror, but whatever happens off-screen remains a mystery to us, which only makes the events of the film even scarier.

The Innocents

What's scarier, the possibility of ghosts and demons, or the dark crevices of the human mind? Jack Clayton's 1961 masterpiece, "The Innocents," takes that question to its most frightening conclusion. Based on the Henry James novella "The Turn of the Screw," the inspiration for Mike Flanagan's "The Haunting of Bly Manor," the film follows Miss Giddens (Deborah Kerr), a governess tasked with looking after two orphans (Pamela Franklin and Martin Stephens) in an old mansion. After witnessing supernatural events around the house, Miss Giddens comes to believe that the children are possessed.

"The Innocents" is one of the most visually stunning horror films ever made. Shot in CinemaScope, Clayton uses the extra wide screen not to show more ghosts, but to emphasize darkness. The dark corners and hallways of the house are so deep and unrelenting that you almost wish something would appear in the shadows. But Clayton isn't interested in making the audience jump. Instead, it's the ambiguity that terrifies. The film amps up the uncertainty of the novel, suggesting though not confirming that these supernatural phenomena are all in Miss Giddens' head, giving us no relief in the form of an exorcism or seance.

Under The Skin

In "Under the Skin," director Jonathan Glazer gives us very little information about the film's plot or characters. Scarlett Johansson, giving a career-best performance, plays a woman known as Laura. But Laura isn't a human being — she's an alien wearing the face and body of a woman. Her objective, as far as we can tell, is to lure men into her van so she can harvest their bodies for some unknown alien purpose. These men think they're about to have sex with a beautiful woman, only to find themselves sinking into a black goo from which they will never escape.

Laura is a blank slate. When we first meet her, she lacks any sort of human emotion, acting simply as an observer on Earth, there to carry out her purpose. But as she encounters more of humanity, she can't help but be affected by what she experiences, and her indifferent mask begins to soften. Still, Laura remains a terrifying figure, and her dispassionate observations about the world make it seem a very cold, indifferent place. "Under the Skin" moves at a glacial pace, eschewing horror conventions and forcing us to sit with the unsettling images we're witnessing.

The Haunting

Though Robert Wise's 1963 film "The Haunting" scores low on the jump scare scale, both Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg have called it one of the scariest films ever made. Scariness is subjective, of course, but the film illustrates how subtlety can prove more effective than excess. Based on Shirley Jackson's famed novel, the film follows anthropologist Dr John Markway (Richard Johnson), who wishes to study the paranormal phenomena that supposedly occur at Hill House. He invites Eleanor (Julie Harris), a troubled young woman with a ghostly past, and Theodora (Claire Bloom), a brash psychic, to stay at the manor.

"The Haunting" contains the trappings of a haunted house film, venturing into a gothic mansion filled with things that go bump in the night. But these typical scares are kept to a minimum, and Wise's film, like Jackson's book, keeps the real terror of the story in the psychological realm. Eleanor is a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown from the moment she enters the house, and her deteriorating mental state drives the movie's descent into spookiness. The presence of Theodora, an unapologetic lesbian, prompts us to consider haunting as a matter of emotional and psychological difference, rather than the top-down imposition of ghouls and poltergeists.

The Wailing

Na Hong-jin's "The Wailing" follows one man's search for meaning, with devastating consequences. Jong-goo (Kwak Do-won) is a cop in a small mountain town in South Korea. A series of violent killings plagues the town, and they seem to be connected to an outbreak of a mysterious illness. Paranoia, prejudice, and a lack of answers lead townspeople to suspect the involvement of a Japanese man (Jun Kunimura), who recently moved to town.

Jong-goo's investigation lacks a sense of urgency until his daughter contracts the same illness, spurring the indifferent cop to action. But Jong-goo's love for his daughter is no match for the cosmic power at play. He turns to religion for answers but can't comprehend the scope of the curse that's afflicting the town. As viewers, witnessing the horrific events depicted on screen makes us feel like we're seeing something we shouldn't, like we might be cursed as well. "The Wailing" doesn't frighten us using typical horror tricks, instead reminding us that the scariest thing is knowing nothing at all, making it a must-watch.

They Look Like People

At its core, "They Look Like People" is about friendship, a rare theme for a horror movie. MacLeod Andrews plays Wyatt, a man whose grasp on reality seems to be slipping. A series of mysterious phone calls leads Wyatt to believe the apocalypse is imminent, and humanity is at risk of being infected by an alien entity. While preparing for a war only he is aware of, Wyatt reconnects with an old friend, Christian (Evan Dumouchel), who tries to help Wyatt get back on his feet.

"They Look Like People" is a sparse film, using limited locations, actors, and few special effects. Its most impressive element is sound design and score. Wyatt is tormented by a buzzing sound that may indicate an extraterrestrial invasion, and the soundtrack rises and falls (in a very eerie fashion) in time with the emotions of the characters. It's an inward-focused film, brilliantly building tension almost out of thin air. It's up to the audience to decide if Wyatt is really privy to the coming apocalypse or in the midst of schizophrenic delusions. Both are harrowing prospects, and director Perry Blackshear develops these frights without the sudden appearance of monsters.