15 Best Movies Like Get Out

2017's "Get Out" is one of the great feature film debuts in modern history, if not all of filmdom. Jordan Peele, best known up to that time as a comedic writer and performer, shocked the world with a socially-minded horror-thriller about a Black man named Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) who visits the parents of his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams) and discovers a terrifying conspiracy. It was a colossal box office hit, won an Oscar, and was recently named the eighth-best film of the 21st century by the New York Times.

Whether you've recently experienced "Get Out" for the first time or have revisited the sunken place on multiple occasions, we've got a collection of similar films to scratch that particular itch. Some are explicit comments on the ills of our world, others are darkly comedic horrors willing to dive into the grotesque, and all will take you on a wild ride.

Here, then, are the 15 best movies like "Get Out." Just try not to stir your tea too loudly while watching.

Attack the Block

In the working-class London streets, Moses (John Boyega's breakthrough role) and his gang are trying to get by however they can, including committing low-level crimes. But these problems become overshadowed — and in some ways exemplified — when terrifying, flesh-eating creatures from outer space invade Earth, and these young men have to both defend the block and, well, "Attack the Block."

Joe Cornish's cult classic is funner and funnier than Peele's often nerve-shredding debut; I'd even go so far as to call it a "romp." But like "Get Out," "Attack the Block" starts as a social drama about race, class, and white liberal uncomfortability (personified here by a subtle Jodie Whittaker) before hard-pivoting into genre mayhem.

It's a gripping, gritty, and authentic-feeling thrill ride, one that makes you fall in love with its characters before subjecting some of them to some genuinely upsetting and gnarly creature carnage. Plus, the creature design, especially for the low budget Cornish was working with, still holds up – and they were apparently just as terrifying behind the scenes.

The 'Burbs

Joe Dante is a special director: a madcap maverick who blends dark comedy, abject horror, 1950s kitsch, and a volume knob I'd call "cartoon but louder." Even for him — and especially for star Tom Hanks — "The 'Burbs" is a particularly odd watch, but it's better than what you'd expect from the reviews.

Hanks plays Ray Peterson, an everyman who loses his mind as he investigates the increasingly strange happenings of his new neighbors, the Klopeks. He believes there's darkness, mayhem, and murder hiding at the core of the Klopeks, and he'll stop at nothing to find the truth, no matter the cost. Think "Rear Window" meets Daffy Duck, and you're close to "The 'Burbs."

Tonal disparities aside, "Get Out" shares a position with "The 'Burbs" that the greatest source of fear hides underneath the most civilized of society. The idea that idyllic Americana is a front for a rotten set of guts isn't exactly novel, but "The 'Burbs" wins points for turning that idea up to an absurd, violent degree.

Candyman (1992)

"Candyman" was such an influential text for Peele that he ended up co-writing and producing a smart, scary, and multidimensional legacyquel. "Though the original has some fascinatingly problematic notes," Peele told the Los Angeles Times, "it changed my perspective of what was possible in film by daring to represent Blackness in what was, for me as a genre fan, the ultimate position of power."

Tony Todd's iconic performance as the titular monster is, indeed, suffused with power. His Candyman appears when you say his name in front of a mirror, and he's ready to get you with bees and a hook hand. But his tale, adapted from a Clive Barker short story, is tragic, romantic, and explicitly informed by racism, adding complicated and, yes, "fascinatingly problematic notes" to his relationship with Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen).

At the heart of "Get Out" is an inherently tragic romantic relationship between two races, a dynamic radiating with asymmetric power dynamics and malicious obstinance. Its resolution, like Peele's experience with "Candyman," does ultimately position Blackness in the ultimate position of power.

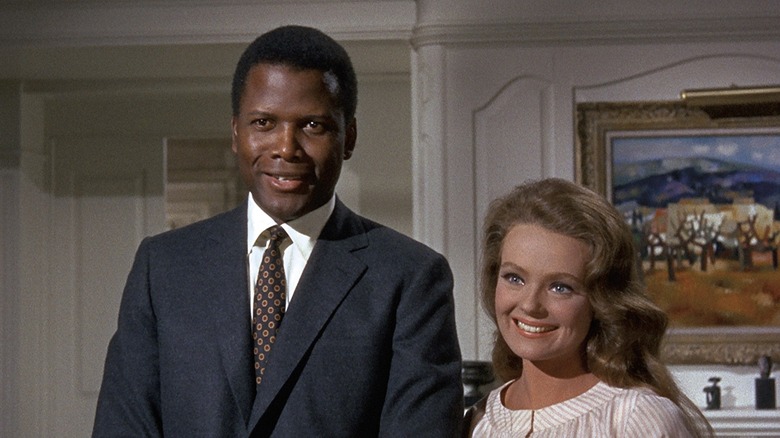

Guess Who's Coming to Dinner

In writing his Academy Award-winning screenplay for "Get Out," Peele took direct influence from 1967's "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner." He told podcast host Jeff Goldsmith that "one of the reasons that film was so effective in its discussion with race is because it started with a situation that was universal. Take the race out of it, everybody can relate to the fear of meeting your potential in-laws for the first time." He took that structure, turned it horrific, and there's your "Get Out."

"Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" — which also scored a Best Screenplay Oscar win for William Rose — plays this scenario as a drama-tinged comedy. Katharine Houghton brings her new fiancé, the brilliant Sidney Poitier, to meet her parents, played by Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. What results is an agonizing conflict between ideals, realities, and good old-fashioned prejudices as the parents waffle in their support of the union.

To me, the white parents of "Get Out," Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener, almost feel like they've watched "Guess Who's Coming to Dinner" as research, and are determined to "win" the quiet race conflict brewing at their table with performative stabs at allyship. Of course, it's all a front.

The Invitation (2015)

Every time I watch "Get Out," my stomach drops when Chris learns how deep the sickness of the body-harvesting society goes. If you'd like that feeling stretched and dripped over a slow-burning 100-minute movie, I simply must recommend "The Invitation."

Directed by Karyn Kusama (who also gave us the true cult classic "Jennifer's Body"), "The Invitation" similarly starts with a universal anxiety: Will (Logan Marshall-Green) is taking his new girlfriend (Emayatzy Corinealdi) to a dinner party hosted by his ex-wife (Tammy Blanchard). Awkward! And it gets even more awkward as, around the dinner table, Will realizes the hosts have some kind of nefarious, violent, and cult-like scheme up their sleeves.

Why are we so afraid of cults? It's not just because they have enforcers like John Carroll Lynch to get what they want (though I can't stress enough how terrifying he is in this film). I think it's because we're worried we'll get subsumed by them easily. One of our biggest anxieties is "ruffling feathers," and if a group of charismatic folks has figured out how to seduce people into self-destruction calmly and politely, how can we strike back beholden to society's rules? Isn't it easier to just give in?

Luce

2019's "Luce" is a barn-burner: a stirring psychodrama based on a play with a ton to say about contemporary American race relations in a post-Obama world.

A revelatory Kelvin Harrison Jr. plays the title role, a beloved high school student who was adopted by two white parents, Naomi Watts and Tim Roth (who previously played a danger-laden upper-class couple in 2007's "Funny Games"). But when the star athlete and honor roll whiz kid starts expressing ideas of anger and violence, particularly against his history teacher (Octavia Spencer), the tightly-wound, superficial niceties in the community unfurl and explode.

Despite its roots in stage drama, "Luce" plays close to a horror movie over its runtime, so raw and incendiary are its provocations and conclusions. Harrison brings such well-observed specificities to the screen, all layered in the types of masks this type of person needs to wear. It's one of the sharpest and smartest films you'll see about the unspoken anxieties burbling under the American surface since, well, "Get Out".

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

One of the greatest and most influential horror films ever made, George A. Romero's "Night of the Living Dead" inspired so many essential things we know about the zombie genre, the independent film, and how Black heroes are seen in genre cinema.

It was an explicit influence on Peele, especially in its central relationship between Ben (Duane Jones) and Barbara (Judith O'Dea), two normal humans doing their best to survive an inexplicable zombie uprising. As he told the New York Times, "The lead in 'Night of the Living Dead' is a man living in fear every day, so this is a challenge he is more equipped to take on than the white women living in the house. Chris, in his racial paranoia, is onto something that he wouldn't be if he was a white guy and there was a similar thing going on."

While "Night of the Living Dead" has a famously pessimistic ending (lead actor Jones fought against a happier one), Peele seems to have purposefully flipped the script, giving his audience something to cheer about. Less dead, more living.

No Way Out (1950)

Another classic in the "Sidney Poitier enters a majority-white space and deals with everyone's white bull" subgenre, "No Way Out" stars Mr. Poitier as Dr. Luther Brooks, the first Black doctor at his hospital. Two white brothers and criminals (Dick Paxton and a particularly vicious Richard Widmark) burst onto the scene with injuries, and Dr. Brooks does his best to uphold the Hippocratic Oath despite their abject racism. When treatment goes awry, all hell breaks loose, pitting Dr. Brooks into an all-out race war across the city.

1950 was a big year for director Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who also released the beloved showbiz drama "All About Eve," based on a sad, real-life story. While that film remains appealingly authentic and gritty by 1950 standards, "No Way Out" remains a shocking and provocative depiction of evil and hatred.

To paraphrase Mr. Peele, it does strike some fascinatingly problematic notes, especially in the constant need for Poitier's character to remain "above" the grungier fray of the white characters, making a modern viewer wonder if the filmmakers only thought a white audience could relate to Dr. Brooks if he stays "civilized." But even these elements make for a fascinating, illuminating pairing with "Get Out" as an evolution of the race-relations thriller.

The People Under the Stairs

Wes Craven's bizarre and straight-up icky "The People Under the Stairs" is another film so influential to Peele that he signed on to produce a remake (a remake, as of this writing, we've still yet to see).

In the 1991 horror satire, a lower-class Black character nicknamed Fool (Brandon Adams) is convinced by Leroy (Ving Rhames) to rob the home of his landlords to pay for his mother's surgery. Fool's landlords are the Robesons (a cartoonishly terrifying Everett McGill and Wendy Robie), who are already perceived by the community as eccentric and corrupt. But when Fool's robbery goes awry, they discover awful and vicious truths about the Robeson family secrets, especially when it comes to the identity of those people under the stairs.

Peele programmed this film for a series on social thrillers, telling the Village Voice that it "represents, whether intentionally or not, a certain fear of what goes on behind closed doors in white homes. And it also approaches the notion of enslavement of the people they've got hidden under the stairs." In "Get Out," Peele took this fear of enslavement to its highest extremes, having his white characters literally steal Black bodies. No need to hide under the stairs, in that case.

Rosemary's Baby

Another classic in the horror canon, though not without controversy, "Rosemary's Baby" stars the harrowing Mia Farrow as the newly pregnant Rosemary who lives in a New York City apartment with her actor husband Guy (John Cassavetes in absolute weenie mode). But what should be a milestone of joy for the couple turns into a slow and steady drip of tension and terror for Rosemary as their overly friendly neighbors seem unwelcomely invested in the fate of her baby.

Peele programmed this film in the same social thriller block, and it's not hard to draw parallels between it and "Get Out," as both position an outsider character within a group of people that slowly cross from "polite" to "eerie" to "the most evil people you'll ever meet". They also both share a harrowing plot twist involving a romantic partner's betrayal, though "Rosemary's Baby" ends on that narrative move as the ultimate tragedy, while "Get Out" uses it as the propulsion for its climax.

Sorry to Bother You

Boots Riley, like Jordan Peele, moved into feature filmmaking from a separate yet related creative field (music for Riley, comedy for Peele). And Riley's "Sorry to Bother You," like Peele's "Get Out," is a mind-bending social satire.

Cash and Detroit (LaKeith Stanfield and Tessa Thompson) live a life of art and revolutionary politics — which is to say, they're dirt poor and struggle endlessly with the increasing dehumanization of modern life. But when Cash scores a gig as a telemarketer, he learns a nifty trick to get more money: just use your "white voice" (in this case, David Cross dubbing over Stanfield). But that act of racial assimilation triggers one of the wildest conspiracies you'll ever see on screen.

There's nothing subtle about Riley's vision, which takes the ideas of scavenging racial identity present in "Get Out" and plays them at the most heightened registers possible. It's an audacious work you have to see to believe.

The Stepford Wives (1975)

Katharine Ross moves with her husband and children from the busy streets of New York City to an upper-class Connecticut community called Stepford, putting some of her aspirations to bed along the way. What she finds are a group of beautiful, well-mannered women who exhibit complete dependence on their husbands and erratic, even robotic behavior. Are these wives of Stepford under some sort of nefarious mind control? And will Ross' character be next?

There's a particularly chilling scene in "Get Out" where Andre (LaKeith Stanfield) is triggered out of his stupor enough to cry in anguish and scream at Chris the title of the movie. This central tension powers all of "The Stepford Wives," another social thriller that influenced the films of Jordan Peele, albeit one with a more explicitly comedic tone.

It's a film ahead of its time with lots to say about our ever-oppressive patriarchal society. It's also the second film based on an Ira Levin novel on this list, after "Rosemary's Baby," making Levin quantitatively one of the most important authors for the conception of "Get Out."

Tales From the Hood

1995's anthology horror film "Tales From the Hood" is, in some key ways, a dated watch, trafficking in some nihilistic stereotypes about Black city life present in other 1990s hood movies. But it's also an important watch in relation to the study of horror movies from Black directors – and at more times than you'd expect, it remains an excoriating, provocative, and timely watch.

The vignettes presented in Rusty Cundieff's film run the gamut of social issues plaguing Black folks, from police corruption to literal Ku Klux Klan members. And like many anthology movies, it has a framing story involving a group of young drug dealers striking a Faustian deal with eccentric mortician Mr. Simms (the powerful Clarence Williams III).

Also like many anthology movies, the vignettes can vary in quality, and many of them feel on-the-nose. But I especially stump hard for the first piece, "Rogue Cop Revelation," a nightmarish work of American tragedy.

Us

If you love "Get Out," it simply makes sense to continue through Jordan Peele's filmography! "Us," his second film, was the box office hit that gave him true power in Hollywood.

Adelaide (Lupita Nyong'o) and her family take a vacation to Santa Cruz, California, despite the fact that she suffered a bizarre, traumatic event there in her childhood. But on the first night of their visit, a group of home invaders appear, with blood on their minds. And they're not just any home invaders: they are perfect doppelgangers of every member of Adelaide's family, led by the atrophying yet purposeful Red (Nyong'o again).

"Get Out" keeps its focus pretty tight, spinning a yarn about a cult and conspiracy that more or less plays out in one house. "Us" takes some of Peele's first film's themes and expands them out to a grander, even apocalyptic level, putting the entirety of American existence under a magnifying glass until the sun makes it burn. It's a chilling, violent, and queasy watch — and Nyong'o not getting an Oscar nomination for her dual role should be a federal crime.

The Wicker Man (1973)

To track the influence of "The Wicker Man" on "Get Out," listen to composer Michael Abels' exceptional score of the latter. It's in dialogue with the ancient, the tribal, and the ritual, catapulting Peele's film out of its contemporary milieu back into our past traditions of communities and enemies. It makes the film a piece of folklore, just like "The Wicker Man" (which has its own surreal soundtrack).

In "The Wicker Man," Neil Howie (Edward Woodward) is our outsider protagonist, a police sergeant investigating the disappearance of a little girl on a strange, isolated Scottish island. But during his detective work, he discovers this island practices some strange form of Paganism that is more than willing to turn deadly, all under the grim and imposing eye of Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee, of course).

"The Wicker Man" ending is one of the most famous in horror cinema, representing the sublimation of good into evil, of the individual into the cult. And it uses traditional music to communicate this idea viscerally, as the perpetrators of vile acts sing.

But, just like "Night of the Living Dead," Peele twists this iconically pessimistic ending into one of forward progression. By placing his film in dialogue with "The Wicker Man," musically and otherwise, Peele wonders aloud if triumph can be possible.