Clint Eastwood Fired The Director In The Middle Of Shooting This Classic Western

By the time Clint Eastwood had finished his three-movie stint with Sergio Leone, he was not only the face of the "Dollars" trilogy that introduced American audiences to spaghetti westerns, but also one of the biggest movie stars in the world. His Rowdy Yates days on the CBS western "Rawhide" were well behind him now, with the silver screen calling to him more than ever. The world was his oyster. Eastwood's time in the industry would ultimately accentuate one of his biggest characteristics as a creator, with that being a total sense of control over production. Along with his financial advisor Irving Leonard, Eastwood co-founded The Malpaso Company (now called Malpaso Productions), which has produced just about every one of his films from the Ted Post-directed western "Hang 'Em High" all the way up until 2024's stellar courtroom morality drama "Juror #2."

Malpaso would allow Eastwood to maintain some semblance of oversight on his starring vehicle projects, in addition to paving the way for the celebrated actor to make the leap to director. He'd already gotten that itch to be behind the camera while shooting "Rawhide," but finally had enough industry clout to do so on his own terms with 1971's "Play Misty For Me," a psychological thriller by the sea about the darker side of free love. Eastwood, over the next few years, would follow up his directorial debut with the horror western "High Plains Drifter," the May-December drama "Breezy," and the James Bond-esque action-thriller "The Eiger Sanction." The actor-director, however, ran into some trouble with his next production, "The Outlaw Josey Wales."

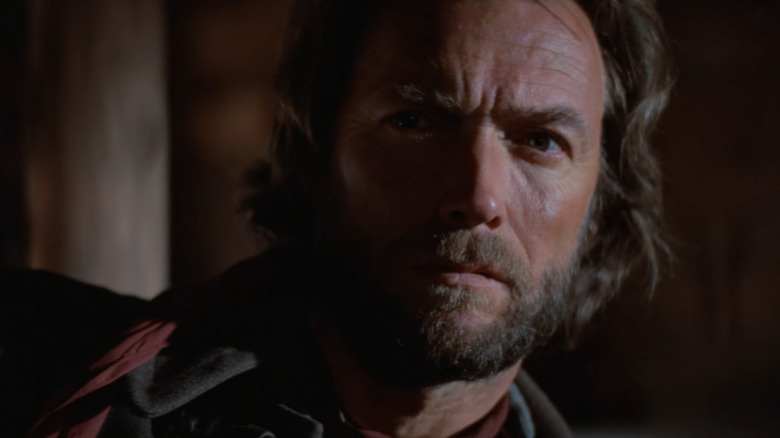

The 1976 revenge western stars Eastwood as a Missouri farmer who becomes a Confederate soldier after a Union paramilitary group murders his family. Come the end of the American Civil War, the titular Josey Wales becomes a sought-after criminal. The hardened figure, however, has no intentions of turning himself over without a fight. Eastwood dances with some prickly material, yet the film is a great revisionist western about picking up the pieces of a shattered life and the admirable trials of avoiding more bloodshed, however futile it may seem given the circumstances. He's credited as the film's director, but that's a whole journey in and of itself, especially since "The Outlaw Josey Wales" was initially the brainchild of director Philip Kaufman.

Kaufman, who later went on to direct 1978's "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" and "The Right Stuff," was slated to make the film for Warner Bros. in conjunction with Eastwood and Malpaso. While the film's star had paid his share for the screen rights to the 1972 novel from Asa Earl Carter (who went under the pseudonym Forrest Carter), it was Kaufman, along with "Thunderbolt and Lightfoot" director Michael Cimino and screenwriter Sonia Chernus, who penned the screenplay. With the filmic development of "The Outlaw Josey Wales," however, came a considerable amount of strife between Kaufman and Eastwood to the point that the latter ended up removing the former from the set altogether.

Philip Kaufman was let go from The Outlaw Josey Wales over creative differences

To say that Clint Eastwood and Philip Kaufman clashed over the material is an understatement. Both had different approaches on how to tackle the material, with Kaufman wanting to veer away from the fascistic political overtones of Carter's novel, while Eastwood didn't. The novel's author turned out to actually be a man named Asa Earl Carter, who not only lied about his Cherokee descent, but was also revealed to be a staunch ally to the KKK and Alabama Governor George Wallace. The film adaptation ends up being a nuanced character drama that miraculously isn't as much of a fascistic piece of Confederate revisionism as the novel is.

After a week of production, however, Eastwood simply had enough of not being able to steer "The Outlaw Josey Wales" in the direction he wanted it to, firing Kaufman from the film by way of his producing partner Robert Daley (via "Clint Eastwood Interviews"):

"When it came to shooting, he just had a little bit different ideas of the style of the film. And I did have my own money in it, and I bought the book from scratch, and I just felt I didn't want to see it portrayed that way. So it was strictly a point of view. Nobody will ever know, but for all we know his ideas might have been the best. I just had a line on it and loved the project and didn't want it to be done the way he was going to interpret it. And he didn't want to do it the way I wanted to do it. There wasn't any animosity or disrespect for him in any way, shape, or form."

Another source of contention revolved around actress Sondra Locke in her first of many collaborations with Eastwood. In addition to being his screen muse, Locke is also known for her very public affair with the then-married Eastwood. Kaufman protested her being cast in "The Outlaw Josey Wales" as the character Laura Lee, but the Malpaso head honcho pushed for it all the way. There were even rumors surrounding Kaufman sharing a mutual infatuation with the up-and-coming actress. Eastwood may be an excellent filmmaker, but boy, did he know how to cause drama in his personal life.

Eastwood's mutiny over Kaufman's film came with its own share of consequences, one of which led to a rule that's still in effect today.

Kaufman's firing led to the DGA implementing a new rule in Eastwood's name

It's hard enough to get a movie made as is. When you're upending the figurehead of the entire production, however, that's sure to ruffle some feathers among the crew, and sure enough, it did. The decision to eject Philip Kaufman made Clint Eastwood an unpopular figure on set. Among the loudest criticisms of the actor-director's decisions was the Director's Guild of America (DGA), which slapped Eastwood with a $60,000 fee for the unprecedented inconvenience.

The biggest ripple wave effect of the Kaufman debacle resulted in the now-infamous mandate from the DGA called "The Eastwood Rule." You would think getting a decree authorized in your name would be an honor, but in this case, it was anything but. It stipulated that, barring an emergency, it was prohibited for a producer, actor, or any other creative force to discharge the director once they've started production. It set a precedent that Eastwood, himself a member of the DGA, would encounter while starring in the sleazy '80s cop thriller "Tightrope," where he met some resistance in usurping the film's screenwriter-director, Richard Tuggle.

Of the many things you can say about Eastwood, he was undoubtedly a control freak, albeit one who eventually learned to play the cards as they were dealt to him in any future production he was a part of.