How An Unsolicited Story From An Infamous Political Figure Became Clint Eastwood's The Outlaw Josey Wales

One of the cardinal Hollywood sins for an established talent is to accept unsolicited material. To do so not only encourages other aspiring screenwriters to inundate agencies and production companies with scripts, it also places the recipient in a potentially vulnerable position legally. Basically, if an idea is fertile enough to merit a greenlight, it's not beyond the realm of possibility that someone else has had a similar idea. And if that writer can prove he sent that script years prior to the artist who turned that similar idea into a successful movie, that artist might find themselves on the business end of a plagiarism lawsuit.

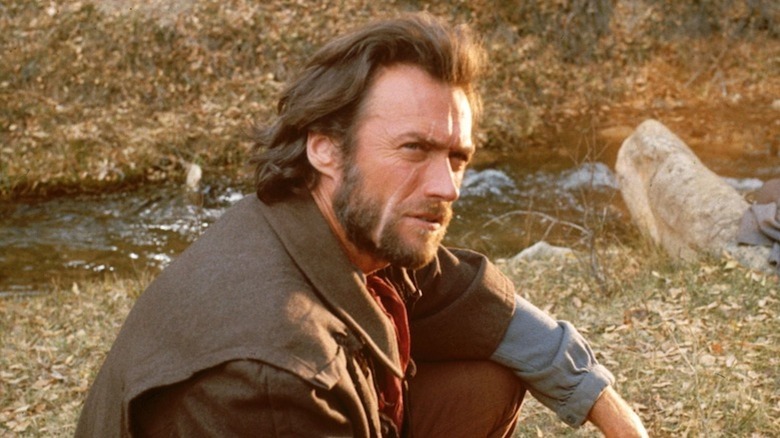

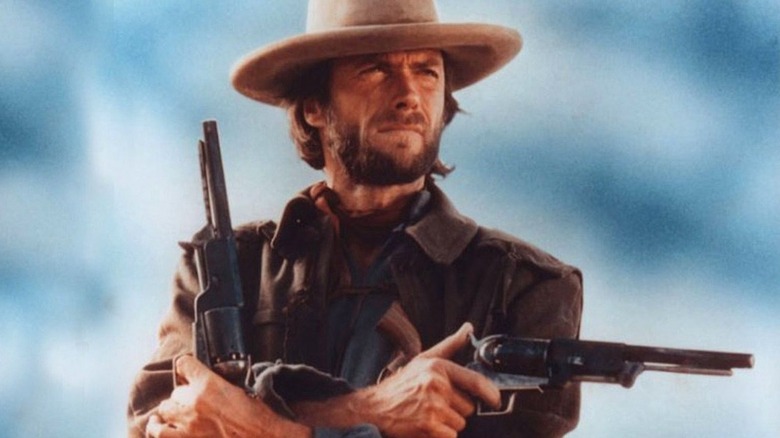

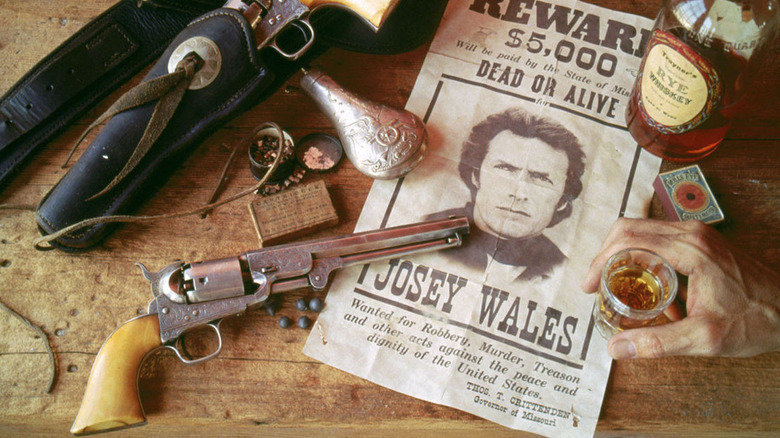

So it's surprising that in the early 1970s, Clint Eastwood, who'd made his name on Westerns and had many more in active development, acquired the rights to an unsolicited novel called "The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales" by Forrest Carter. According to an interview with Patrick McGilligan, the star's assistant, Robert Daley, made the call based on a cover letter that "had a nice feeling about it." He gave the book a 20-page read, and soon found himself absorbed in an epic, Civil War-era tale about a Missouri farmer turned gunfighter in the wake of his family being massacred by Union affiliated Jayhawkers. Daley fired the book off to Eastwood, who was at his home in Carmel, California, and the rest is history.

And that history, particularly the identity of the author, is awfully interesting.

Unsolicited material from an unreliable narrator

Eastwood had just wrapped "The Outlaw Josey Wales" when he chatted with McGilliagan, and he praised Carter as "a half-Cherokee Indian with no formal education including grammar school. He's a terribly self-taught person who became famous as an Indian poet and teller of stories." This was a lie. Carter's real name was Asa Earl Carter. He was a former speechwriter for George Wallace, the segregationist governor of Alabama. In 1970, Carter ran against his mentor on an independent, white supremacist platform; when he lost, he withdrew from the spotlight and reinvented himself as a Cherokee author.

Eastwood's attraction to the material was, on a certain level, practical. As he told McGilligan:

"It's about the character I play, whereas in 'The Good, the Bad and the Ugly' the only character you got to know — somewhat — is the Eli Wallach character. In other words, Josey Wales is a hero, and you see how he gets to where he is — rather than just having a mysterious hero appear on the plains and become involved with other people's plights."

Sonia Chamus got the first crack at adapting Carter's book, and she was later joined by Michael Cimino and Philip Kaufman. Eastwood initially hired Kaufman to direct, but the two were soon at loggerheads as to the presentation of the material. Kaufman abhorred Carter's politics. In an interview with Slate's Allen Barra, Kaufman said the following:

"'Fascist' is an overworked word [...] but the first time I looked at that book that's what I thought: 'This was written by a crude fascist.' It was nutty. The man's hatred of government was insane. I felt that that element in the script needed to be severely toned down. But Clint didn't, and it was his movie."

Movies are so much more than the sum of a solitary creator

Some believe one of the cardinal film critic sins is the inability to separate the art from the artist. I subscribe to this theory. I have to. Film is a collaborative medium. The work speaks with more than one voice. Even a film as deeply personal as Steven Spielberg's "The Fabelmans" bears the unmistakable mark of screenwriter Tony Kushner, who's written movingly on the experiences of Jewish people in America and the world at large. A director may try to shape an actor's performance, but they cannot manipulate them frame-by-frame like a stop-motion figure. Every actor has their say, and any director who knows a thing about a thing knows to let that actor add their verses to the chorus.

I adored Eastwood's "The Outlaw Josey Wales" long before I knew the identity of its originator. When I learned of Carter's past, I was, of course, aghast. This man was a force of evil for much of life. And yet, in his last decade, he wrote "The Education of Little Tree: A True Story," a tale of multicultural understanding that counts Henry Louis Gates as an admirer (Oprah Winfrey endorsed the book in the 1990s, but withdrew her support when she learned of the author's identity). I cannot speak to what was in that man's heart, but I do know that Eastwood's movie is a stirring anti-war saga. It's about the ruinous cost of hate.

When I watch "The Outlaw Josey Wales" today, I don't see Eastwood on stage at the 2012 Republican National Convention — where he strode out in front of a pistol-wielding silhouette of Wales — belittling an imagined Barack Obama as an inarticulate imbecile. I don't think of Carter's bigotry. I'm captivated by a revisionist Western lousy with layers. Did Eastwood and Carter mean to make a work with such complexity? Their intent doesn't matter. Per my reading of their film, they did.