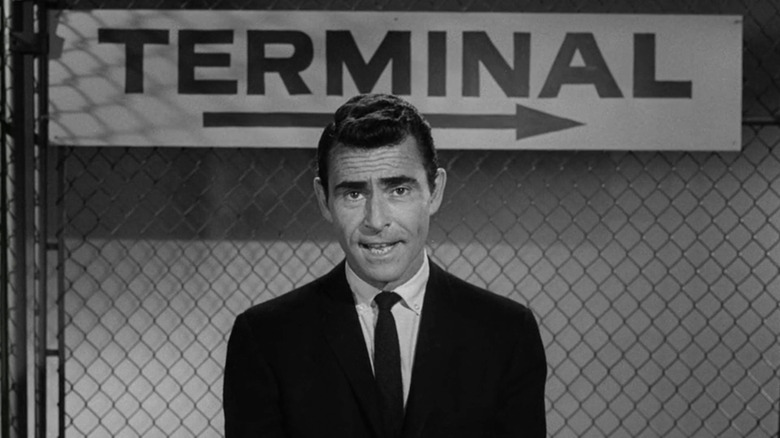

Rod Serling's Wax Museum: The Twilight Zone Sequel That Was Buried Before It Began

True lightning-in-a-bottle phenomena are immensely difficult to recapture. 60 years after "The Twilight Zone" completed its initial run in 1964, subsequent attempts to resuscitate the property — either with an anthology film or reboot series — have failed to match its cultural impact, even with vaunted directors Steven Spielberg, George Miller, Wes Craven, William Friedkin, Jonathan Frakes, Ana Lily Amirpour, Justin Benson & Aaron Moorhead, and Osgood Perkins lending their talents behind the camera. It's a testament to everything the late Rod Serling accomplished with his surreal amalgamation of genre storytelling and social commentary that we tend to overlook his many other significant contributions as an artist (which include co-penning the 1968 "Planet of the Apes" movie).

When the original "Twilight Zone" ended, however, its legacy seemed far from assured. Serling had burnt himself out after writing so many episodes for the series, with the consensus being that the show's final two seasons were far less consistent in quality than the three before them. Compounding matters, CBS elected to give the initial time slot for season 4 to "Fair Exchange," a '60s comedy series that was radically structured for its era but ultimately unsuccessful and only further contributed to Serling's growing sense of disillusionment behind the scenes. All the same, "The Twilight Zone" continued to fare well in the ratings game and was still more than capable of knocking it out of the park late into its tenure (as it did with all-time notable episodes like season 5's "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet").

Despite this, the show was canceled after five seasons, and left to find a new home — a turn of events that led to Serling developing a failed pitch for a sequel series known as "Rod Serling's Wax Museum."

'Stories of the weird, the wild, and the wondrous'

In an interview from Marc Scott Zicree's indispensable "The Twilight Zone Companion," the "Twilight Zone" producer William Froug claimed that CBS' then-president Jim Aubrey "decided he was sick of the show" and canceled it, citing poor ratings and the show being over budget (neither of which was accurate). Serling subsequently received an offer from ABC to continue the series under the title "Witches, Warlocks, and Werewolves" (named after the 1963 fantasy and horror anthology novel he had edited) to avoid copyright infringement. Instead, Serling did the network one better and proposed a sequel in the form of "Wax Museum."

Much like the original "Twilight Zone" opening title sequence, every episode of "Wax Museum" would have begun with a series of dissolves, this time moving towards Bolt Castle (which Serling described as a "haunted house" in his pitch). Therein, Serling would guide the camera to a shrouded figure, which would turn out to be a wax figure of the episode's protagonist. Serling would narrate this process as follows:

"A hearty welcome to my wax museum. For your entertainment and edification, we offer you stories of the weird, the wild, and the wondrous; stories that are told to the accompaniment of distant banging shutters, an invisible creaking door, an errant wailing wind that comes from the dark outside. These are stories that involve the citizenry of the night. In short, this museum is devoted to ... goose flesh, bristled hair, and dry mouths."

Watch enough of "The Twilight Zone" and you can practically hear Serling enunciating every one of these words in his particular fashion. "Wax Museum" sounded promising enough, striking the same sinister tone as its parent series while creating an eerie vibe all its own. Sorry to say, though, artistic differences killed the show before it even started.

Serling didn't want to be 'hooked into a graveyard'

While "The Twilight Zone" frequently dabbled in supernatural horror, it never lived there. As early as its third episode, the Western fantasy installment "Mr. Denton on Doomsday," the series established that any genre was fair game for its writers so long as they threw in a twist that had no basis in real-world logic (one of several "rules" Serling put in place for "The Twilight Zone" that he and his collaborators would gradually bend to the breaking point). Yet, for whatever reason, ABC's president at that time, Tom Moore, was dead-set on the strictly fantasy-horror angle he'd envisioned with "Witches, Warlocks, and Werewolves."

As Serling told Daily Variety after meeting with the executive:

"[Moore] seems to prefer weekly ghouls, and we have what appears to be a considerable difference of opinion. I don't mind my show being supernatural, but I don't want to be hooked into a graveyard every week. [...] I don't think TV can sustain C-pictures every week."

Moore was quick to respond to Serling's statement, informing the press ("with apparently no pun intended," as Zicree observes in his book), "We have buried the project." Perhaps it was for the best; Serling thrived from having the freedom to zig and zag as he saw fit on "The Twilight Zone," so locking him into a single corner of horror reads like a bad idea. That and, as mentioned earlier, the magic of his original creation has proven remarkably difficult to replicate in the many years since it ended, so it might have taken more than the slight alteration in the format offered by "Wax Museum" for Serling to strike gold again.

Or maybe "Wax Museum" would have rejuvenated Serling creatively. The answers to such questions can only be found in ... well, you know where.