The Most Famous Comic Writer Of All Time Wrote A Three Page X-Men Story For Marvel

Alan Moore is a comic writer responsible for countless classics, but what most people remember him for is his work at DC Comics: "Watchmen," "Batman: The Killing Joke," etc. Moore himself, though, has disowned these works, since they're owned by the company that screwed him over on creators' rights, and he maintains disinterest in discussing them or adaptations.

I'll say this since I'm one of them — comic fans can be quite thin-skinned. So, they've turned Moore and his current dislike of superhero media into evidence that he's just a grouchy and bitter old man. As a counter-argument, I'll present a Twitter thread from his daughter Leah Moore (herself a comic creator), one written in defense of her "internet-averse" father.

Mrs. Moore documents how her father fell out of love with superhero comics, the passion of his youth, as he got a firsthand look at the dirty machinery of the industry. Her point which hit me hardest is that, if the comics industry wasn't so hostile to artists, its lifeblood, then maybe Alan Moore would still be writing superhero stories today and the genre/its fans would be richer for it.

Can you imagine if he hadnt been fucked over? If instead of being Grumpy Alan Moore Shouting From His Cave he had spent the past 40 years putting out book after book for DC and the rest? Creating vast worlds full of the superheroes he loves? Enjoying comics? Its a damn shame.

— Leah Moore (@leahmoore) November 21, 2019

It's a sad thought to ponder, with considerations far beyond Moore; how many great stories have never been heard because their potential makers had the misfortune of being born into an unfair world?

Frankly, Marvel/DC would benefit from Moore more than he would from them (he's continued writing creator-owned work and never lost his skill). Even so, a three-page "X-Men" story by Moore from 1985, one of the only Marvel Comics he wrote, shows a glimpse of the stories we might have in the world where DC didn't screw him.

X-Men by Alan Moore

In 1985, Marvel published a collaborative issue — "Heroes for Hope: Starring the X-Men" — with proceeds going to African famine relief. The issue — featuring the X-Men attacked by a psychic entity — had an all-star writer line-up, including Stephen King and Moore.

Moore's story is about Magneto. At the time, the Master of Magnetism was a good guy, teaching the New Mutants while his frenemy Professor X was otherwise engaged (the upcoming cartoon "X-Men '97" looks to be loosely adapting this). Moore, though, suggests redemption is not so simple.

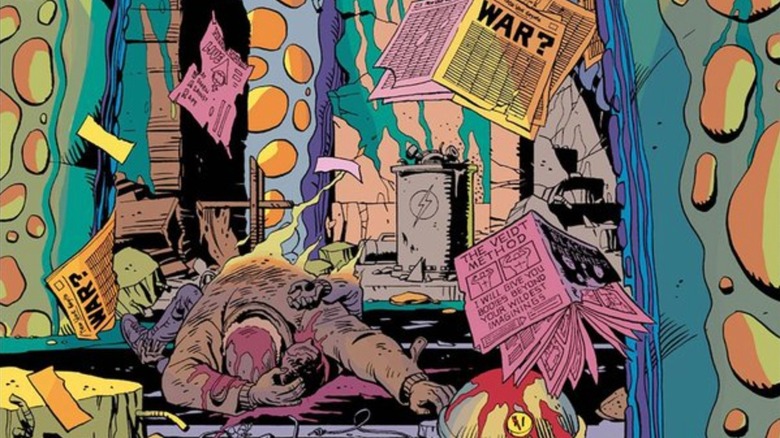

The story (drawn by Richard Corben) begins with Magneto gazing upon Cerebro, the psychic tool amplifying Professor X's power. Magneto puts on the helmet and the entity strikes, plunging him into an apparently imaginary world where he and his former Brotherhood of Evil Mutants have won, conquering the world but with only a wasteland to rule. A walking crowd of mutilated corpses shambles towards Magneto, who stares at his helmet in horror (interviewed in Speakesy magazine, Moore noted the symmetry of the first and last panel wasn't in his script, citing how comic writers must collaborate with artists for a greater whole).

Alan Moore was born in 1953 and would've been raised on the early 1960s Marvel stories overseen by Stan Lee. In those "X-Men" books, Magneto is a megalomaniacal villain, with none of the depth from later comics or the films. Notice how Moore features Magneto's old Brotherhood, like the Toad and Scarlet Witch; his DC stories similarly incorporate Silver Age of Comics imagery. (His Superman story "Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow" is a finale to that era's ensemble, while "The Killing Joke" shows a framed picture of the 1950s Bat-family.) Even as he took superheroes seriously, Moore never hid how silly the stories could be.

Magneto's mountain of corpses

One person who is a fan of Moore's Magneto was Chris Claremont, who wrote "X-Men" from 1975 to 1991, making the book into the powerhouse it is these days. In fact, Claremont is the one who first conceived of Magneto as a Holocaust survivor. In a 2018 interview with SYFY, Claremont said "Thank God!" that Moore didn't write anymore "X-Men" stories — because then he would've had steeper competition.

So, what does Moore's "X-Men" story mean? There's a potential optimistic reading, that Magneto is being shown what would have happened had he carried on his former villainous path. But the issue's final line ("The hands of the dead are upon me, and I do not even have the right to scream") doesn't leave the reader, or Magneto, feeling well.

One could read the unliving dead as representing those who have already died in earlier battles, the casualties of Magneto's quest for mutant supremacy. His guilt is thus not fear of what he could have become, but a reminder of what he's already done. Moore, as cynical about superheroes being a net good as he is, is thus using this story to highlight the absurdity of a destructive supervillain (like the Magneto of his youth) making a face turn.

The central image of Moore & Corben's Magneto story — a murderer surrounded by the vengeful and moving bodies of their victims — is one I've seen in several comics. I think the medium, which has sequential continuity but not real motion, is especially useful for portraying such imagery; a comic invites a reader to linger on a single frame and absorb its details in a way you can't with a film.

From Watchmen to manga

Take "Wonder Woman" #6 by George Pérez (co-written by Len Wein), the finale of his 1987 relaunch. Diana confronts Ares, the God of War, who plots to spark a nuclear armageddon. So, Diana shows him the lonely world he'll rule if he triumphs; a tearful Ares relents. This realization about a destructive dream is similar to Moore's Magneto.

More directly mirroring Corben's "corpse crowd" is the manga "Vinland Saga" by Makoto Yukimura. That series follows an 11th-century Viking warrior named Thorfinn, who kills many in a failed effort to avenge his father. After the first 60 or so chapters, his mission changes from vengeance to atonement. So that the reader understands Thorfinn's cross to bear, certain panels show him surrounded by a mountain of corpses, as he imagines himself to be. If he kills again, that means adding another body to that toll.

Yukimura's influence probably isn't American comics, though, but Kentaro Miura's "Berserk." In that manga, a crippled mercenary leader named Griffith is given the chance at power if he sacrifices his followers. To sway him, he's shown a vision of all the people he's killed, their bodies forming a (still-incomplete) walkway he stands at the edge of. Griffith's conclusion is the opposite of Thorfinn's; if he doesn't take more lives, the previous deaths will be meaningless. Under different writers' pens, Magneto has wielded both these arguments.

Looking at Moore's work itself, though, the overlaps I see are "Watchmen" and "Miracleman." In the former, Adrian Veidt/Ozymandias kills thousands in the name of greater peace. In the latter, the story concludes with the hero using his Superman-like powers to change the world, building a benevolent dictatorship. Moore, an anarchist, is skeptical of men with a will to power who are out to exercise it over the world. If their vision is fulfilled, the bodies will pile up.