How The Twilight Zone Used TV To Mourn The Death Of Radio

What made the original television run of "The Twilight Zone" (from 1959-1964) so special was the way individual episodes could function on multiple levels. Since the show was an anthology, and every episode had its own premise, it was free to explore whatever it wanted to. The first level of a given episode was the superficially exciting one that put you in the shoes of a protagonist faced with an unnerving science-fiction premise. But the other level went deeper, studying human nature at extremes. Host and show creator Rod Serling would show up to deliver the moral, but the twists, unhappy endings, and central ironies continue to be surprising and disturbing.

The series typically explored prejudice in the form of racism or anti-intellectualism, or in one of its most famous episodes, the idea of beauty standards. But it also explored nostalgia, whether for a bygone way of life or for the one that got away. For a show always aimed at speculative ideas of the future, the past was often in its sights.

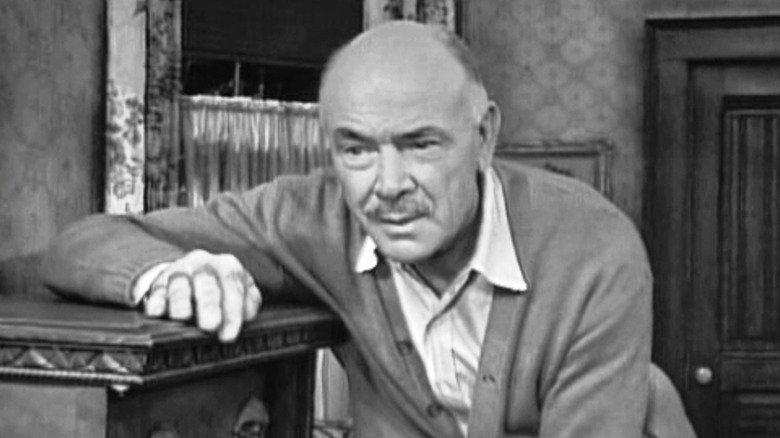

Of the handful of "Twilight Zone" episodes addressing the idea of nostalgia, the classic "Kick the Can" is probably the standout episode. But the 1961 episode "Static" is another excellent one. It takes a fairly basic premise — a man named Ed (Dean Jagger) discovers an old radio still receiving broadcasts from 1940, but only he can hear it — and uses it as a tribute to lost love and the medium of radio that had lost its relevance in the wake of television. Considering how much "The Twilight Zone" made a case for the young medium of television being capable of real art, "Static" takes a fairly cynical view of it.

Charles Beaumont ... in the Twilight Zone

The episode was written by Charles Beaumont from a story by his friend OCee Ritch. Beaumont was one of the seminal writers of "The Twilight Zone," ultimately writing almost two dozen episodes of the show. As a writer of short stories, he would have been a huge influence on any science-fiction storytelling anyway, but as a television writer, he created an incredible legacy. His work was responsible for some of the show's most memorable moments, including episodes like the Death Row nightmare "Shadow Play," the ironic space travel saga "Elegy," and, of course, "Static."

"Static" came out of discussions Beaumont had with Ritch at a party held by fellow legendary sci-fi writer (and "Twilight Zone" scribe) Richard Matheson. According to the guidebook "The Twilight Zone Companion," Ritch was reminiscing about the radio and ended up writing a story called "Tune In Yesterday" about a radio that broadcast from the past. Beaumont encouraged Ritch to submit the story to the show, and then he ended up adapting it, incorporating many of his own additions to fill out the episode's runtime.

In doing so, he came up with one of the more stage-bound episodes of "The Twilight Zone," a far cry from the dangerous location shooting of season 1's "The Lonely." Most of it takes place in a boarding house and a bedroom. That stagey quality may make the episode less engaging than some other classics of the series, but it fits the story, and it lends the episode the quality of a rich character study with a nice helping of satire.

A private time machine

Opening on a handful of older people living in a boarding house, watching television, "Static" satirizes the medium of television immediately. One of the first things you hear as they watch the television stupefied is an advertisement for "Green, the new chlorophyll cigarette." There's no room in this world of television for art, or even for the enriching qualities of a mass communication media. Another boarder leaves the dinner table early so that he can catch the television show "Gunfire," a clear reference to "Gunsmoke."

But Ed, a deeply sad and bitter man for reasons that become clear as the episode rolls on, can't take the television anymore. The endless advertisements and the numbing violence and the rock and roll hold none of the same charm for him as the old radio he finds in the basement and drags up into his room. When tuned to a particular station, Ed seems to get a live broadcast — not from 1961, when the episode aired and takes place, but 1940, when he first met the love of his life Vinnie (Carmen Mathews). He hears a presidential address from Franklin Delano Roosevelt and after trying to contact the station, learns that it's been shut down for 13 years.

Many "Twilight Zone" episodes veer into horror territory, and one of the scariest episodes even got a follow-up in another iteration of the series. But that's not true for "Static," where Ed relishes his bizarre, time-traveling radio. Nobody else in the house can hear it — it's his own trip to the past. As he tells the other boarders, "Radio is a world that has to be believed to be seen."

Ed tunes in

The key thing for Ed is the music. Instead of rock and roll, he hears Tommy Dorsey's "I'm Getting Sentimental Over You," the song he and Vinnie called their own when they were young lovers 20 years ago. The two of them met in the boarding house, fell in love, and ultimately went their separate ways when Ed kept pushing off their marriage. The radio is a window to a world where nothing has gone wrong for Ed yet. It's the closest he can get to a second chance with Vinnie and with his life.

Vinnie, who still lives in the boarding house with him, tries her best to get Ed to move on, and other boarders think his obsession is unhealthy. Eventually, they sell the radio to a junk dealer and Ed hunts it down, buying it back for 10 bucks. His reward is an actual second chance. When Vinnie enters his room in the episode's final scene, she's young again, still in love with Ed. Ed is young again too. He can do it right this time, even if the radio will still be supplanted by television in just a couple years. It's not a twist ending like the show was known for, but an emotionally complex, bittersweet grace note.

The themes of nostalgia, regret, and feeling your time has passed you by are eternal. The episode is more dated by the fact that the instrument of nostalgia is the radio. If it was already old-fashioned in 1961, that's even more true now. But that aspect of the episode was very personal to its writer, Charles Beaumont.

What we had

Ed's dislike of television? That was a Charles Beaumont contribution to the original story of the episode by OCee Ritch. While "Static" doesn't make for one of the show's most relevant episodes now, Ed and Beaumont's view of television still resonates.

"Television is the substitute for what we had, and I deem it a bad one," Beaumont wrote in his 1963 essay collection "Remember? Remember?" "It does not thrill, transport, terrify or enchant. It only entertains." Elsewhere in the essay, he discussed how "radio was real to us" and how it inspired imagination and gathering. Television, on the other hand, is a heavily commercial medium, contorting itself to the demands of advertisers and money-crunching executives. While "Static" criticizes television by using the medium of television, the most incendiary point it makes against the medium came from outside of the show's control.

Near the end of the show's second season, CBS insisted that too many episodes were skating close to their $60,000 budgets. To cut costs, according to "The Twilight Zone Companion," the network forced the show to film six episodes on primitive, low-quality videotape that would get printed over to 16mm film for broadcast. Shooting on videotape rather than film meant that the filmmakers would be forced to shoot more in the manner of live television, which led to "Static" having longer, more dialogue-driven scenes than was typical for the show. It ensured the episode would be less visually evocative than many of the show's more memorable episodes by limiting its narrative to interiors.

But the cost-cutting, rather than detract from this particular episode, led to a touching episode about the ravages of time and human limits. And in "The Twilight Zone," artists could produce something great in spite of the demands of the medium.