How Twilight Zone's Rod Serling Pioneered The Sci-Fi Genre For Years To Come

One might see Rod Serling's 1959 sci-fi anthology series "The Twilight Zone" as an ambitious amalgam of all modern genre writers. Prior to production, Serling famously solicited scripts from some of the best-known sci-fi writers of his time, including the likes of Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, Malcolm Jameson, and several others. Serling typically wrote the scripts for "The Twilight Zone" himself ... which led to some occasional accidental plagiarism. "The Twilight Zone," then, was somewhat of a culmination of an entire generation's sci-fi literature.

Now handily condensed, many of the more striking speculative tales of the day could be easily consumed by a mass public. Serling's show was a huge hit and lasted five seasons before going off the air in 1964. Sering later wrote "Planet of the Apes" in 1968.

Thanks to syndication deals and Thanksgiving marathons, "The Twilight Zone" lingered in the pop consciousness for decades, eventually spawning a movie in 1982, and revivals in 1985, 2002, and 2019. Audio episodes of "The Twilight Zone" also ran on BBC Radio from 2002 to 2012. All five seasons of Serling's original series can currently be found on Paramount+ and Freevee, and four of them are on Pluto TV. The show has never left us.

It also, it goes without saying, changed the cultural landscape. Numerous authors, filmmakers, and high-profile sci-fi fans have openly proclaimed their love of the show, and how Serling's particular brand of speculative, twist-ending morality fable shaped the way they made art. Some authors, like George R.R. Martin, were aided rather directly by "The Twilight Zone," as the future writer of "A Song of Fire and Ice" worked on the 1985 revival. Others, like M. Night Shyamalan (obviously) merely took inspiration from the show's structure.

But "Zone" fans are legion. Here are some others.

Mel Brooks, Twilight Zone fan

On the PBS website for American Masters, several notable artists were put on the record as to their fandom of Serling's show. One might easily guess that Jordan Peele was a fan of "The Twilight Zone" as he served as executive producer and narrator for the 2019 revival. It will also shock no one to learn that Stephen King and Guillermo delt Toro are massive fans. King said in Marc Scott Zicree's sourcebook "The Twilight Zone Companion" that he was inspired by Matheson in particular, while del Toro, although a "Twilight" fan, was more fond of Serling's follow-up series "Night Gallery."

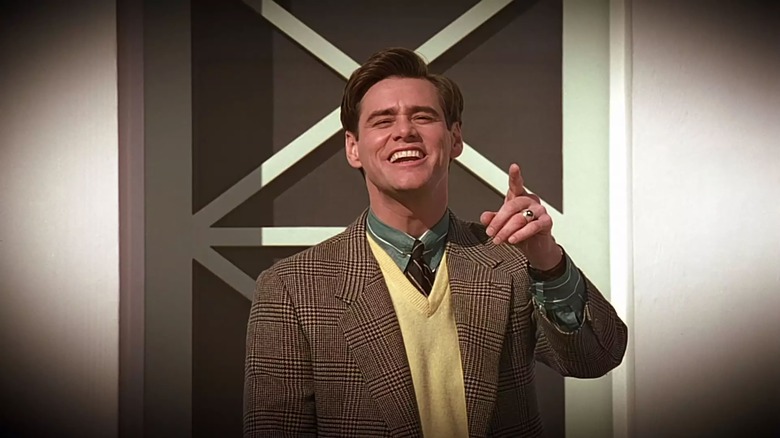

One might be a little more surprised to learn that comedian Mel Brooks was a fan. Brooks, of course, had taste in entertainment that extended far beyond the comedies he was known for writing, as the maker of "Blazing Saddles" also produced films like "The Elephant Man" and "The Fly." Brooks clearly had a thing for the unusual and the macabre and was impressed by Serling's mastery over his production. In Mark Dawidziak's 2020 book "Everything I Need to Know I Learned in the Twilight Zone: A Fifth-Dimension Guide to Life," Brooks offered the following observation:

"The greatest lesson I learned is that you need to reserve judgment and seriously buy into the creation and design of the filmmaker. You've got to give it all up and go along with the magic. Every time I watched 'The Twilight Zone,' I was completely ready to surrender to it. That's what the mystery of creation is all about. Give yourself over to that wonderful, wonderful mystery."

Brooks doesn't draw a straight line between his enjoyment of "The Twilight Zone" and his interest in the filmmaking of David Lynch and David Cronenberg, but we can easily imagine it.

A few others

Dawidziak's book also noted that another comedian, Carol Burnett, was a fan, just as Serling was a fan of Burnett's. Eventually, the latter wrote an episode called "Cavender is Coming" specifically for the former. It was the only episode of "The Twilight Zone" to feature a laugh track.

The influence of "The Twilight Zone" can also be seen through any number of references and homages on other TV shows. There are multiple "Twilight Zone" riffs, for instance, in many of the "Treehouse of Horror" episodes on "The Simpsons." The famous episode "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" (October 11, 1963) — about a gremlin on the wing of a plane and the panicked passenger who sees it — was reimagined on a school bus in "Terror at 5½ Feet." The "Zone" episode "Living Doll" (November 1, 1963) was retooled to be about a killer Krusty the Clown doll in "Clown Without Pity." The very first "Treehouse of Terror" featured a species of sinister aliens who owned a book called "How to Cook Humans," a clear reference to the twist ending of the "Zone" episode "To Serve Man" (March 2, 1962). There was a twist in "The Simpsons" too: the book was actually called "How to Cook For Forty Humans."

Likewise, "It's a Good Life" (November 3, 1961) became "The Bart Zone," "Little Girl Lost" (March 16, 1962) became "Homer3," "A Kind of Stopwatch" (October 18, 1963) became "Stop the World, I Want to Goof Off," and "The Little People" (March 20, 1962) became "The Genesis Tub." There's no denying that Matt Groening was a huge fan. Perhaps notable: all of Groening's adaptations came from the third season of "The Twilight Zone."

Anthology sci-fi

The notion of sci-fi anthologies was nothing new and goes back at least as far as Hugo Gersback's 1926 publication of Amazing Stories Magazine. In the 1950s, many major studios backed sci-fi anthology radio shows like "Beyond Tomorrow," "X Minus One," "2000 Plus," "Quiet, Please," "Escape," and "Suspense." The format had also already been explored on TV prior to "The Twilight Zone" in shows like "Tales of Tomorrow," "Science Fiction Theater," and "Fear and Fancy." Serling hardly invented a medium.

Still, his show was so popular that it became a cultural fulcrum for all sci-fi anthology shows that were to come after. To this day, any modern sci-fi anthology show will inevitably be compared to "The Twilight Zone." In the '50s and '60s, "Zone" had contemporary competitors in shows like "The Outer Limits" and "'Way Out," but it was Serling's show that led the pack. Netflix has produced two notable "Zone" riffs, including the animated series "Love, Death & Robots," and the massively popular "Black Mirror." And, just like in Serling's time, "Black Mirror" has seen a slew of fad-chasers in the form of shows like "Channel Zero" and "Philip K. Dick's Electric Dreams."

Technically EC's "Tales from the Crypt" comics predated "The Twilight Zone," so the many anthology horror shows inspired by publisher William Gaines' stories are on a track of their own. "Tales from the Crypt," "Tales from the Darkside," "Monsters," and "Creepshow" are their own thing.

"Eerie, Indiana," however, owes "The Twilight Zone" its very existence. Whether or not R.L. Stine, the creator of "Goosebumps," was more inspired by Serling or Gaines is a matter that can be debated. Stine, however, did contribute to "Twilight Zone: 19 Original Stories on the 50th Anniversary" edited by Carol Serling, Rod's widow.

Other stories besides

And, of course, one can see small "Twilight Zone" influences in myriad other places. Movies like "Identity," "Source Code," and "Moon" have Serlingesque plots, and other films lifted off individual "Twilight Zone" episodes wholesale. "Special Service" (April 8, 1989) was a clear influence on Peter Weir's 1998 film "The Truman Show." Some have even seen "Little Girl Lost" as a source of inspiration for Tobe Hooper's 1982 film "Poltergeist." Although he hasn't adapted a "Zone" story, J.J. Abrams' fondness for mystery box plots on TV shows like "Lost" and cleverly secretive ad campaigns for films like "Super 8" certainly owe Serling a doubt.

Serling's overwhelming influence on modern American entertainment is all the more astonishing when one discovers that he felt that he wasn't contributing anything. A 1970 documentary, presented by the Hollywood Reporter, revealed that Serling was deathly afraid of being forgotten in time. He had a "desperate hunger to go back," clearly having regrets. Esther Gray Peacock, one of Serling's students (he served as a professor) remembered him pulling her aside. "The last time I saw him," Peacock said, "out of the blue he looked at me and said 'I just have this horrible feeling I'll never be remembered ... I'll never be a Hemingway.'"

Serling is not Hemingway, but he is Serling. He always felt that science fiction was a too-often-dismissed genre and that he aimed to legitimize it in the eyes of studios and moneymen who pooh-poohed sci-fi as "kids stuff."

Given where we are in 2023, one might say that he achieved his goal 10 times over.