15 Episodes Of The Twilight Zone That Are Still Relevant Today

It's always struck me as something of a marvel that "The Twilight Zone" has managed to avoid feeling dated, despite the final episode being broadcast more than 60 years ago. Spanning five seasons between 1959 and 1965, at its best, the show depicts facets of the human condition that are universal, with many plot points, themes, and warnings that remain relevant today.

Rod Serling, the show's creator (and writer of 92 out of 156 episodes) always had an eye for themes that transcended the various settings. The presence of Serling himself in a business suit, offering wry commentary on the episodes, means that however futuristic the environment, they have an almost timeless quality that helps make the series endure. Almost counter-intuitively, this also serves to add to the series' eerie aesthetic.

Some episodes were incredible for their time and still hold up but watching today, the plot mechanics feel a little more predictable; due in no small part to the show's direct influence on pop culture in general. Any casual viewers of "The Simpsons" will have had several twists spoiled outright by various "Treehouse Of Horror" homages. This list focuses more on episodes that feature themes that have not lost their significance in a modern context, and indeed, some that are more relevant now than when they first aired. With current events rapidly overtaking the then-far-fetched plots of many episodes, the stories often seem like a series of prophetic nightmares that we are now experiencing first-hand.

Third from the Sun

A somewhat throwaway episode that nonetheless hits differently today, "Third from the Sun" presents a dystopian future that's not so different from our modern day, with two nations on the brink of a nuclear apocalypse. There is a vaguely defined fascist state in place, as government weapons workers plan to escape the planet and find a new one to inhabit, "11 million miles away."

Serling would confront the idea of ideological fascist dystopias in later episodes like "The Obsolete Man," but while that episode veers into preachiness at times, the setting in "Third from the Sun" is much more natural. We feel the oppressive regime without it ever being explicitly spelled out, and there is an implied drain of the Earth's resources; importantly, it's clear to us that the planet will not survive whatever happens in the immediate future.

The idea of the inescapable extinction of humanity and the plan of leaving for a better world feel very familiar: a world with dwindling resources and global warming making our own future pretty bleak (although for us it's likely the multi-billionaires who will do this, leaving the rest of us behind). Also, the oppressive regime and imminent nuclear war, as well as the ideas of constant surveillance all feel relatable today. It's true there is no immediate threat in the present day, but geopolitical tensions and the threat of global conflict are very real fears, whatever the time period.

Nightmare At 20,000 Feet

One of the most renowned episodes of the series, "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet" has been parodied, remade in the feature film, and even reinvented in Jordan Peele's reboot of the series. Written by regular "Twilight Zone" contributor Richard Matheson, the episode's enduring relevancy has less to do with the supernatural elements of the story, and everything to do with the main character (William Shatner) and his increasingly frantic attempts to warn the flight crew about the gremlin he sees on the wing of the plane.

Watching today, it's impossible to not imagine yourself in the situation Shatner's character finds himself in. Also, increased security around commercial flights and the public's fear of the perils of airline travel further make this episode chilling to watch with a contemporary mindset.

Even more potent, though, is the increasing hysteria of Shatner's performance, and especially the reactions of those around the character. He at first tries to convince himself he is imagining the monster, and the flight crew subtly indulges what they perceive as his ravings when he subsequently confides in them; Shatner's dismissive attitude when he realizes they are just humoring him is a lovely touch. It's all so plausible. Of course, if you found yourself in a similar situation, you would panic. And, of course, everyone would think you were crazy. You just know if this ever actually happened today we would all be doomed.

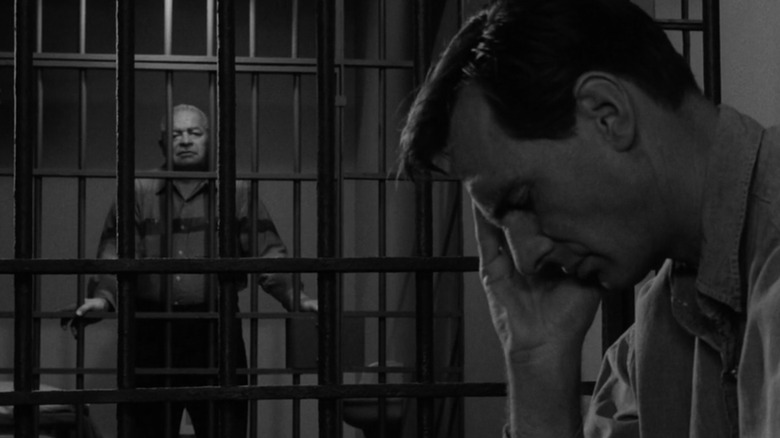

Shadow Play

The question of whether our experiences are real or dreams is a concept that has existed since Socrates and his shadows on the wall. It's such a pervasive idea that it has served as the basis for literature, art, and pop culture, including in "Inception," "The Matrix" and "Edge of Tomorrow."

"Shadow Play" was by no means the first television episode to explore the nature of reality, but it ranks among the most effective examples. Adam Grant (Dennis Weaver) is condemned to death, whereupon he breaks down and explains that he is in a recurring nightmare, and if they kill him, this entire world will blink out of existence.

It's an existentialist, thought-provoking episode that's ahead of its time in so many ways — a post-modern, almost meta half-hour of television, that draws attention to the borders between dreams and reality. Charles Beaumont's witty script makes a virtue of the low budget by addressing it in the script, pointing out the cheap prison set design, and even the use of the harmonica-playing convict. It all but draws attention to the fact this is a TV show, adding yet another layer of artifice.

"Shadow Play" remains relevant today due to the way it explores ideas surrounding reality, especially in the current era of virtual reality, "alternative facts," and "fake news," where we are often encouraged to disregard the evidence of our eyes and ears. It's a prophetic episode of television, with a genuinely disarming ending.

Nick Of Time

In William Shatner's first appearance on "The Twilight Zone," he plays Don, a young, superstitious accountant whose trip with his rational girlfriend (Pat Carter) is interrupted by a broken down car, stranding them in a little town. Visiting a local diner, Don notices a Mystic Seer, a fortune-telling napkin holder (with an appropriately demonic visage), and quickly becomes enthralled by the accuracy of its answers.

Superficially, "Nick of Time" is relevant today thanks to the way these childish games enthrall grown adults — if remade, this episode would likely involve someone getting addicted to a new app or online game — but a deeper reading reveals a much more pervasive idea that is all too relatable to contemporary audiences. Don's problem is his uncertainty about his future prospects, grappling with an undetermined future he cannot control, leading him to return to the comfort of the fortune-telling device. Many can relate to this feeling of anxiety in a world where our futures are increasingly unstable and volatile.

What makes the episode work today is the way it says more about Don than the fortune-telling machine. By the end of the episode, we are more or less convinced that the machine does indeed tell the future. But this is almost irrelevant; what matters is that Don finally walks away, tearing himself away from its grasp, unlike the unfortunate couple they pass on their way out.

On Thursday We Leave for Home

Some episodes retain their topicality thanks to a freaky prescience, while others seem to capture a very specific mindset that seems weirdly contemporary. "On Thursday We Leave for Home " falls into the latter group and it rates as the most successful of the hour-long episodes.

In the future, a colony from Earth has crashlanded on a distant planet, with no way to communicate with anyone to arrange a rescue. The self-appointed leader of the group, Benteen (James Whitmore), keeps spirits up with stories of Earth and helps the group to survive and thrive on the desolate planet. Eventually, a rescue ship arrives to take the inhabitants back to Earth, but Benteen is so caught up in being the savior and leader of this little planet that he refuses the offer to return home, only realizing his mistake when the rockets have launched, leaving him stranded forever.

This is maybe an esoteric choice for this list, but watching it today, this episode feels analogous to online communities. In the final summary from Serling, he describes Benteen as "a population of one," which rings very true today. In our increasingly isolated, online existences it's easy to be drawn into arguments and conflicts with others over trivial subjects, often to the detriment of those that really matter. Twitter feuds, and forum spats, can blind us to the things that are genuinely important.

Death's-Head Revisited

"Death's-Head Revisited" is a fairly straightforward episode, with a central message that still resonates, the result of its furious, sobering approach to the Holocaust.

Former camp commandant Captain Lutze (Oscar Beregi Jr.) revisits Dachau concentration camp after the war. Ostensibly in hiding, he wanders around the deserted buildings with barely suppressed sadistic glee, until he is greeted by former inmate Becker (Joseph Schildkraut). It becomes clear that the captain has wandered into a hell of his own making, confronted by the ghosts of his past. As Becker puts it in his final speech: "This is not revenge. This is justice. But this is only the beginning. Your final judgment will come from God."

An intense, passionate anger — something rarely seen today — drives this episode. At its beginning and end, characters question why concentration camps like Dachau are still standing. Serling addresses this in his closing monologue, saying they must remain standing as monuments to the inhumanity and sadism that the human race is capable of, and as a warning to ensure these atrocities are never permitted to happen again. He might as well be justifying why films or television about the Holocaust will never lose their relevance.

When Serling wrote this episode, the Holocaust had just happened, and yet it has lost none of its power. The themes are not only pertinent today but necessary to relive, to keep tackling in any medium, to prevent history from repeating itself.

Miniature

Unhealthy obsession is a recurring theme in "The Twilight Zone." Even more than this, the very specific idea of a protagonist finally projecting themselves into their obsession through sheer force of will crops up more often than you would think. Season Four's "Miniature" is the very best of these, a character study that feels incredibly contemporary, mainly thanks to the gentle performance of Robert Duvall.

As with the finest episodes, this is less about the story's supernatural elements than the characterization of the protagonist. Nowadays we would call the timid, lonely Charlie (Robert Duvall) an introvert, but in "Miniature" he is deemed a weirdo by his family and colleagues. The only thing that seems to make him happy is a miniature doll's house he walks past on his way to work. But as the episode goes on, Charlie's fascination with the dollhouse turns into a fixation.

Charlie's isolation and disconnection from his peers and family feels current, given the rise of the internet and online communities. Nowadays this would resemble somebody losing themselves in their online persona or a hobby that takes over their life, letting them avoid human contact. It's essentially a commentary on escapism, as true now as back when the episode premiered.

The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street

One of the series' most celebrated episodes, and maybe the most famous, "The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street" is a cautionary tale about herd mentality and mass hysteria. Sound familiar? When the lights all go out in the quiet suburban setting of Maple Street, it doesn't take long for hidden prejudices and previously unspoken resentments to come to the surface, and when stranger things start to happen, fingers are pointed all over the street.

The idea of a local community turning on each other because of something as simple as a blackout is very of the moment. The story may have been intended as a McCarthyism allegory, but it wouldn't take much for fear and paranoia to take hold in a similar situation today, with the seemingly constant stream of reactionary misinformation and crackpot conspiracy theories.

The episode highlights how delicately balanced our communities are, and the fragility of the normal social order when confronted with an unseen, nebulous enemy who could be living amongst us. It shows how when fear grips us, mob rule can quickly take over, and if you appear anything other than a full-blooded conformist then you may find yourself at the mercy of the mob. This applies to online communities as well, where doxxing, the Twitter mob, and "the court of public opinion" regularly get out of hand and judge people, often unfairly.

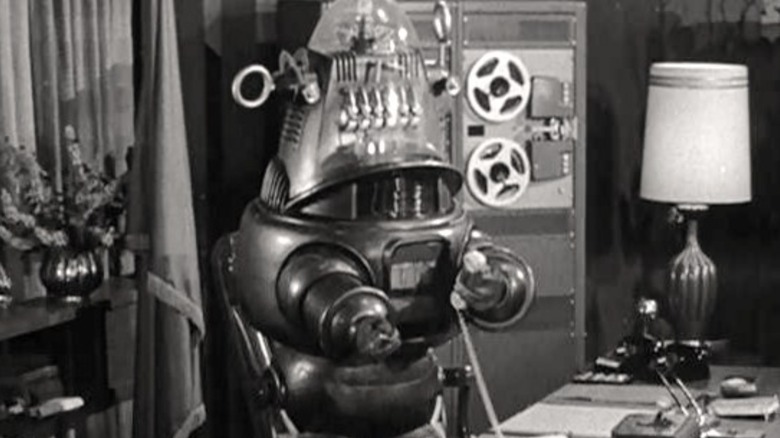

The Brain Center At Whipple's

The clash between technology and humanity cropped up time and time again in "The Twilight Zone," all the way through to the final season. "The Brain Center at Whipple's" is disturbingly prescient today.

Wallace V. Whipple (Richard Deacon) has replaced thousands of his workers with robots in the name of "progress," to increase his factory's work output. Whipple is less a character than a mouthpiece for Serling's concerns about "progress" as a synonym for corporations prioritizing profits and efficiency over human welfare and compassion. Those concerns, it turns out, were well-founded.

Of all the episodes on this list, I consider "The Brain Center at Whipple's" the most topical. There have always been worries regarding how our increased dependence on machines relates to unemployment and job security, but in the wake of the SAG-AFTRA and WGA strikes, and the issue of AI-generated performances putting actors out of work, the role of technology has never been more contentious. The episode even alludes to the notion of ChatGPT, with Whipple replacing his secretary with a machine that ingests his notes and outputs a fully legible agenda.

As an episode of "The Twilight Zone," this is broad and more didactic than "The Lonely" or "Steel," which feature similar messages but delivered with more subtlety. However, for sheer potency and on-the-nose accuracy, this one packs the biggest punch. The almost inevitable conclusion shows Whipple himself out of a job for the same reason as his employees: rendered obsolete by his own creation.

The Shelter

It's impossible to overstate just how imminent the threat of total annihilation was in the late 1950s. Tensions arising from the Cold War were almost overbrimming, so I can only imagine just how chilling season three's "The Shelter" was to watch on first transmission. However, while the Russians were a genuine threat, in this episode the danger lives much closer to home.

The setting is a birthday party for a local doctor (Larry Gates) thrown by his friends and neighbors. The party comes to an abrupt end, though, when a radio newsflash announces that the Russian missiles are flying, and advises citizens to take shelter. Scrambling to their homes, everyone soon realizes that the doctor owns the area's only bomb shelter, and in desperation, they all convene at his house.

Like the best dramas, this episode puts us in the shoes of its protagonists and forces us to confront how we might behave in a similar situation. We'd all like to think we'd be the reasonable one but what makes this episode resonate today is the way it depicts human nature in turmoil. None of the characters is a villain, even those who act abominably. It's just that with the veneer of friendliness and civility irrevocably broken, the primal instinct that drives us to survive reveals itself. The supposedly close-knit community quickly tears itself apart, showing just how fragile the social bonds that exist between neighbors are.

Walking Distance

JJ Abrams once spoke effusively about "Walking Distance," calling it "a beautiful demonstration of the burden of adulthood." He was right.

"You can never go home again" is how the saying goes. Martin Sloan (Gig Young) certainly tries, fleeing his daily grind, however briefly, and returning to his hometown. Upon arrival, it becomes clear that he has somehow traveled back to the summer of his youth 20 years earlier, and even encounters his young self.

The finest episodes of "The Twilight Zone" examine fundamental aspects of the human condition, and this is no exception. The appeal of returning to our youth is especially prevalent now, where increasingly, people retreat into the hobbies and pastimes they enjoyed when they were younger, as opposed to dealing with adulthood (Or "adulting," a term which by its very existence proves why this episode is still relevant).

While "Walking Distance" enjoys a reputation as one of the show's more heartwarming episodes, there is something wistful and bittersweet about the ending. The melancholy with which Martin acknowledges that this summer doesn't belong to him is a universal feeling. We all feel nostalgia for our youth, and our mid-30s are the time when we tend to reassess past life choices and reflect on our past. The episode conveys this perfectly while gently reminding us of the futility of dwelling on the past, instead encouraging Martin to live life in the moment.

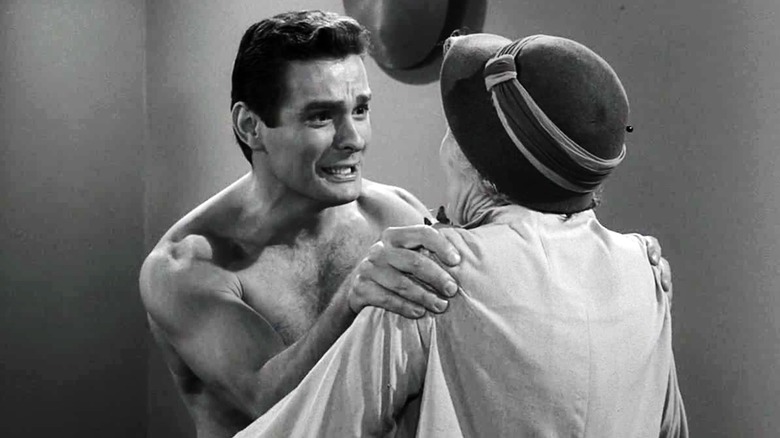

The Trade Ins

The idea of eternal youth, of defeating the aging process, might still seem outlandish but it's becoming more and more relevant, the result of our ever-aging population. Just ask Bryan Johnson, whose efforts to literally age backward to recapture his youth have been well publicized recently.

It's refreshing then, that an episode of television made nearly 60 years ago frames such technical advances as unnatural, instead valuing the finite nature of life, and even making the discomfiting connection between this advanced technology with wealth and privilege. In other words, immortality exists, if you can afford it.

Set in the not-too-distant future, "The Trade-Ins" offers a simple enough premise (and one not dissimilar to "Get Out"), where elderly couple John and Marie Holt (Joseph Schildkraut and Alma Platt) attempt to stave off their imminent demise by trying a new procedure wherein their consciousness will be transplanted into young, perfect bodies that can last more than 100 years. The trouble is they only have enough money for one procedure.

Other episodes show people trying to relive their youth ("Kick the Can") or wistfully yearning for the older days ("Static") but this episode shows the value of growing old together, ending with the Robert Browning quote: "Grow old along with me, the best is yet to be, the last of life, for which the first was made." It begins with the couple determined to prolong their life but closes with them resolving to see out their days alongside one another, making every day count.

A Stop At Willoughby

Fans often compare "A Stop at Willoughby" to "Walking Distance," but the two episodes are more distinct than they first appear. Rather than nostalgia, this later episode primarily addresses the perils of overworking. It's a cerebral take on a similar theme, examining how the mind takes care of itself when it's close to burning out, by retreating into something comforting. However, our protagonist Gart Williams (James Daley), isn't withdrawing into his past but rather looking for a peaceful idyll that he has never known.

Gart is stuck in the wrong profession and overwhelmed by his unforgiving corporate life. Falling asleep on his daily commute, he dreams of a peaceful, old-fashioned town called "Willoughby," and despite being told it doesn't exist, he finds himself compelled to visit the mysterious town. The episode hits home today, as so many of us are pushed to breaking point with long shifts, second jobs, and the increased pressure to keep working. Added to this is the idea that we are supposedly encouraged to be more open about mental health issues and enjoy a healthy work-life balance, while this is too often disregarded by bosses.

The ending initially provides off-kilter comfort. Really, who hasn't wanted to just take the train to its final stop for some respite after a particularly stressful day? However, the closing moments deliver a cruelly subversive twist. Gart finally finds peace, gaining admittance to "Willoughby" by fatally jumping from the train.

Number 12 Looks Just Like You

Standardized ideas of beauty had already been potently examined in the classic Season 2 episode "Eye Of The Beholder," but there's an even slyer, more insidious examination of this theme in the Season 5 episode "Number 12 Looks Just Like You."

Set in an apparently blissful utopia where at age 19 you must choose a physical appearance from a selection of numbered templates that you'll have for the rest of your life. However, 18-year-old Marilyn (Collin Wilcox) resists "the transformation," not wanting to sacrifice her own unique individuality for a conventional standard of beauty.

This is another universal theme that feels pertinent in today's world of photoshopped media and Instagram where users regularly filter out or edit photos that are deemed as not fitting an increasingly narrow definition of beauty. Not to mention the social pressures to aspire to an impossible ideal, leading people to extreme, often harmful methods (plastic surgery) to conform to the homogenized view of beauty perpetuated by film and television.

The episode goes even further, though, connecting conformity to fascism. By the end, not only is Marilyn coerced into changing her appearance but her personal identity and passionate creativity (not to mention her love of "subversive" art and literature) have been replaced by a vacuous optimism. In a line that predicted a near-identical sentiment in "The Incredibles," Marilyn points out "When everyone is beautiful, no one will be."

The Midnight Sun

The ever-pertinent fear of climate change becomes horribly real in this episode, where the protagonists endure a drought, scarcity of resources, endless daylight, and all manner of obstacles before the final nasty sting in the tail.

In an apartment block in New York, Norma (Lois Nettleton) and her landlady (Betty Garde) are the last remaining residents, everyone else having left the city to escape the unbearable heat. The planet has changed its orbit, moving closer and closer to the sun. What follows is a sobering and uncomfortably prescient story about survival in the increasingly hot conditions, until the ultimate reveal. This has all been a fever-induced dream, but before you can even exhale in relief, the other foot drops, and we learn that the planet is still doomed: Earth is actually moving away from the sun, slowly freezing the population to death.

The realities of living in boiling temperatures and the ensuing delirium are depicted in a way that feels incredibly vivid and authentic, from Norma burning her hand on the windowsill or reacting with grim resignation when she spills a bottle of juice.

The devastating effects of climate change are becoming self-evident, and harder and harder to ignore. With the current status of the world's climate crisis evolving from "global warming" to "global boiling," this episode is a sobering and uncomfortably prophetic story, which today feels more like a docudrama than science fiction.