The 15 Best TV Shows Of The 1970s

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

On July 4th, 1976, the United States of America celebrated its Bicentennial. 200 years of existence bred public, country-spanning events and jamborees. But underneath this pomp and circumstance bred a curdling, unsettled need for self-examination, criticism, and change. All of that came, in large part, because of television.

This appliance, now firmly a part of an average household's daily life, became increasingly capable of global transmissions, presenting and reflecting perspectives heretofore unseen. In the real world, government corruption, complicated conflicts, and demands of racial and gender equality rocked and rolled, often in live broadcasts in full color.

So, in the TV world, programs started to follow suit. Thus, not unlike the best movies of the 1970s, shows became exponentially more complex, compelling, and incendiary. Throughout the '70s (and not just in the US, as you'll see with some British entries), the art form expanded more and more, in lockstep with the public's appetite for change and investigation, giving us some truly groundbreaking entertainment.

Here, we've assembled a list of the 15 best TV shows of the 1970s, works that were produced under a time of duress and intrigue, works that prove that the best stuff is often forged through fire.

All in the Family

Startling and provocative to this day, Norman Lear's sitcom masterpiece "All in the Family" garnered explosive audience reactions and found empathy among the shrapnel.

Archie Bunker (Carroll O'Connor) is a deeply prejudiced father and husband, openly antagonistic to people who do not share in his identity or ideological opinions, even and especially when expressed positively by his kindly wife Edith (Jean Stapleton) or stubborn son-in-law Meathead (Rob Reiner).

The show spoke the truth in ways unafraid to be ugly. Archie Bunker was racist, anti-semitic, chauvinistic, and possessed many other unsavory characteristics you'd be hard-pressed to find in a contemporary TV "hero." But the show around him was determined to challenge these nasty beliefs, depicting them with frankness before disarming them with humor. Guest stars like Sammy Davis Jr. would arrive at the Bunker household to disrupt, educate, startle, and provoke shocked laughter, making countless iconic moments of television along the way (Davis concludes his guest starring role by kissing Archie on the cheek, and the audience laughter is as loud as an arena rock show).

The Carol Burnett Show

Sketch and variety shows were ubiquitous in the 1970s, an update of the vaudevillian influence on the still burgeoning medium. One of the greatest and most influential of these is "The Carol Burnett Show," starring the peerless comedienne and a crew of mugging superstars like Tim Conway, Harvey Korman, and Vicki Lawrence (who spun off one of her characters into a 1980s sitcom called "Mama's Family").

Burnett's show featured sly, silly, and subversive sketches that poked fun at the media saturation occurring within its audience while still feeling delightfully indebted to a style of "good old-fashioned entertainment," making it truly enjoyable for all ages.

But if you dislike performers like Jimmy Fallon breaking during live sketches, well, you may have "The Carol Burnett Show" to blame, as many of its episodes with staying power feature cast members losing it at each other. You sense a familial bond between the performers as they crack up, a feeling of support and joy that resonates throughout the best comedy to this day.

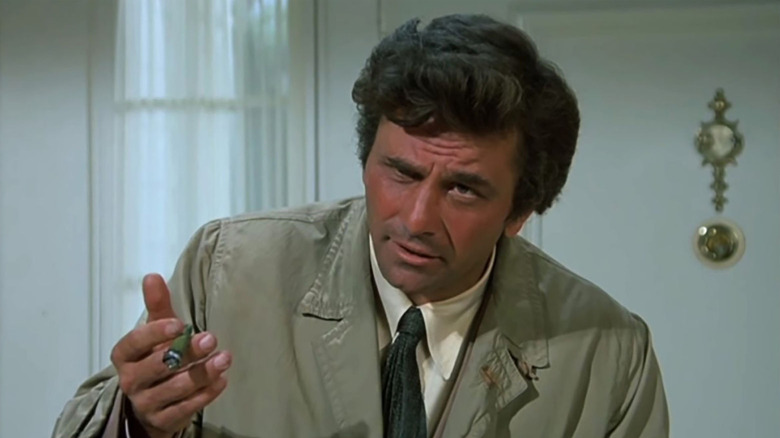

Columbo

Peter Falk is a weird-looking man. Lieutenant Frank Columbo is a weird acting detective. Put them all together, and you get comfort viewing of the highest and weirdest order – a procedural with personality to spare.

"Columbo" helped codify the "howcatchem" murder mystery structure, rather than the more traditional "whodunit". Each episode starts with a depiction of the crime where we see, plain as day, who did it. The joy, thus, comes from Columbo plodding and plotting his way through his suspects, using any matters of unassuming charm and disarming energy to find the truth. Unlike many of the handsome, square-jawed, "just the facts" detectives you'd find in TV history to this point, Columbo felt bristling, authentic, and even annoying, bringing some much-desired shades to the television crime drama.

Oh, just one more thing: Without "Columbo," the career of Rian Johnson doesn't exist, as the filmmaker has spoken many times about the show's power and influence on works like "Brick," "Knives Out," and especially "Poker Face." If you're curious, here are some of the best "Columbo" episodes to watch.

Fawlty Towers

As tightly plotted as an episode of "Columbo," "Fawlty Towers" is farce played to the highest degree, a masterwork of British comedy you'll find resonating through later American TV successes like "Frasier."

John Cleese and Prunella Scales star as the Fawlty family, a husband and wife who run a dysfunctional hotel in a bleary, British seaside town. Cleese's Basil suppresses all of his anger, Scales' Sybil is a shotgun blast of contempt, and the two bicker and claw their way through all matters of shenanigans disseminated with the utmost craft, timing, and professionalism.

Cleese co-wrote the entire series with Connie Booth, who plays the hotel maid and voice of reason, and the purity of their voice shines throughout the 12 episodes. It is, at times, painfully funny, an obvious heir apparent to 21st-century cringe comedies like "The Office" while using the timeless construction of playwrights like Oscar Wilde and Noël Coward to ensure every comedic domino hits with as much efficacy as possible on its way falling down.

The Jeffersons

Spun off from "All in the Family," "The Jeffersons" is one of the best sitcoms of all time. The series stars Sherman Hemsley and Isabel Sanford as a Black couple who "move on up" to a nicer socioeconomic status in Manhattan, New York. With a nicer apartment and more successful business, however, come all matters of conflict, especially given the often discriminatory and limiting nature of the so-called American dream.

"The Jeffersons" was a landmark for Black representation on television that rippled through later iconic works like "The Cosby Show" and "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air," all works that play intelligently and quietly provocatively with the conflicting ideas of capitalism and skin color as American benchmarks. Will one always limit the other, no matter what?

Beyond these big ideas, of course, lies a satisfying, hilarious, and often touching sitcom. In particular, the lead performances of Hemsley and Sanford reach a pinnacle of the form, blending bluster, sensitivity, squabbling, and love to honor the American family no matter what it looks or feels like.

M*A*S*H

In the 1970s, images of the Vietnam War rocked the American living room. Trauma, carnage, and confusing geopolitical ideas blasted in full, living color – not to mention the televised draft threatening to dismantle a family unit with a moment's notice.

To rise to this occasion, Larry Gelbart's "M*A*S*H," an adaptation of Robert Altman's motion picture of the same name, showcased the day-to-day life of medics during the Korean War, a conflict that took place 20 years prior but still allegorically (and literally) touched on the anxieties facing America at the time.

With one of television's greatest casts and a litany of scripts and directing choices more than willing to mess with tone and form, "M*A*S*H" is a game-changing success, a show that's blasted through TV history by making complex choices not just possible, but ideal. Its episodes are smart, often dark in tone, and often sensationally funny. It's experimental but welcoming, political but timeless, and utterly, achingly human. It's a peak of television we'll keep trying to meet.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show

"The Mary Tyler Moore Show" starts with a particularly engaging form of gritted, urban optimism. As Sonny Curtis sings, "You're gonna make it after all," Moore flings her hat into the cloudy, city skyline, and we freeze-frame on its motion, focusing only on the idea that it will rise forever, rather than reckoning with its implied fall.

This sums up the appeal of the show pretty concisely. Moore's character, Mary Richards, does her best to stay positive among the complicated and often sexist environment of a television news production. She is the modern working woman, and dagnabbit, she's gonna make it, no matter what the outrageous (and outrageously funny) ensemble around her does to get in her way!

Co-created by TV icon James L. Brooks, who helped get "The Simpsons" greenlit, "The Mary Tyler Moore Show" pulled off a tightrope walk with effortless-feeling aplomb, honoring the real-world issues of the day and the foibles of its folly-fueled cast while still stuffing their teleplays with accessible jokes and inspiring resolutions. It's a bold, charming, and influential piece of work you'll see rattle through many of your favorite contemporary shows like "30 Rock" or "Abbott Elementary," and many in between.

Monty Python's Flying Circus

Endlessly quotable, absurd to the point of abstraction, and broadening of what "mainstream comedy institutions" are allowed to do on television, "Monty Python's Flying Circus" is one of the key comedy texts.

Its sketches, written and performed by Monty Python's "democracy run riot" of Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin, fundamentally shifted the DNA of comedy construction. They made their audiences smarter, often by making their sketches as stupid as humanly possible. They expanded even the form of "the comedy sketch" itself, blending every vignette into each other, never actually "ending" something, only ever heightening until they had no choice but to blow up even the idea that it was a televised work of construction.

Fourth walls were mere grist for the mill for "Monty Python," a troupe that used its '70s TV run to eradicate boundaries while codifying new, bold types of comedy choices — all building on and cementing the increasingly anarchic world of 1960s British comedy. It's a watershed work, ensuring what we laugh at would never be the same.

Pennies From Heaven

How about another piece of essential British TV?

The 1978 miniseries, written by pervasive iconoclast Dennis Potter, starts as a kitchen sink, working-class drama about an unhappily married couple played by Bob Hoskins and Gemma Craven. But when Hoskins' character Arthur becomes enamored with a woman named Eileen (Cheryl Campbell), a calamitous chain of events begins unfolding with the increasing verve and intensity of a noir-tinged melodrama.

Oh, and also, it's a musical! Throughout the six-episode series, characters burst into musical numbers of classic, Tin Pan Alley-era tunes. This choice is somewhat diegetically justified by Arthur's occupation as a sheet music salesman, but itprimarily functions as a creatively risky, ultimately fulfilling release valve for the characters' repressed emotions. There's canny satire going on here, too. The '70s were a time of reconsideration of and disillusionment with the previous generation's culture, so to use the tunes of a bygone era toward what's simultaneously a safety blanket and an impotent gesture is quite the English middle finger (which is, actually, a V).

The Rockford Files

Hollywood icon James Garner starred in "The Rockford Files," another critically beloved, culturally influential deconstruction of even the best crime dramas. Like Columbo, Garner's Jim Rockford is schlumpy and frumpy, seemingly stumbling into case resolutions by absentminded happenstance that truthfully betrays a cunning mind. Unlike Columbo, however, Rockford works outside of the law. He's a private detective who started his practice in part as a response to a pardoned, wrongful conviction in San Quentin.

While "The Rockford Files" often plays its title hero's misadventures for gentle laughs, his origin story ensures a level of empathy and justice rarely explored to similarly thorough degrees in more traditional policiers of the era. Simply put, Rockford is one of the great TV characters, an intriguing pleasure to watch throughout the show's six-season run, a testament to the idea that tropes like "private eyes" can be jumping off points for authenticity and intrigue in the right hands.

Funnily enough, one of those pairs of hands happened to be writer David Chase, who used this TV experience to help motivate his own show, a little something called "The Sopranos."

Roots

The miniseries "Roots," based on the beloved 1976 novel by Alex Haley, is one of the most important and acclaimed works of television ever made.

Over eight episodes and an incredible ensemble cast, with beloved performers like LeVar Burton, Louis Gossett Jr., and John Amos showing up to hit home runs, "Roots" follows the life and legacy of Kunta Kinte as affected and corrupted by the era of American slavery.

It's pulverizing, intense, and heavy work, and during its initial 1977 airing, it became one of the highest-rated works of television ever, to this day. The public appetite for this kind of programming speaks volumes to the era's desire for reckoning and deconstruction, and the luminous creators of the day's willingness to use the luxury of a mass culture to sway what they felt needed to be said and know it would be heard.

But don't take our word for it. The final say on the importance of "Roots" comes from "That '70s Show" episode "Canadian Road Trip," showing the lengths that grumpy patriarch Red Foreman (a bit of a softer Archie Bunker himself) would undertake to ensure he stays up to date with the times.

Saturday Night Live

"Saturday Night Live" debuted on NBC in 1975, and it's been on the air ever since. Fans and comedy nerds have since debated the show's fluctuating relevance, its best casts, and what it might look like if Lorne Michaels ever retires. And all of this cultural staying power and import comes from five years of chaotic, countercultural, and mind-altering television.

The main actors from the first ever episode? Dan Aykroyd, John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Jane Curtin, Garrett Morris, Laraine Newman, and Gilda Radner. Some of its original writers? Michael O'Donoghue, Alan Zweibel, Al Franken, and Anne Beatts — all supervised by Canadian wunderkind Michaels. Their goal? To bring the unchecked, raucous energy of what the kids loved into the very grown-up world of network television.

They may not have been sure of it at the time, but they succeeded. This original crew (which, during the rest of the '70s, expanded to icons like Bill Murray and Jim Downey) defined and redefined what "live television" and "comedy" can do, expanding the tastes of a mass audience for 50 years and counting.

Schoolhouse Rock!

If you're a reader of a certain age who has some basic knowledge about grammar, history, math, or any other category that might wind up on "Jeopardy!", you undoubtedly have "Schoolhouse Rock!" to thank. Dang, they should really put exclamation points in more TV show titles!

Some children's edutainment is undeniably cheesy. But "Schoolhouse Rock!" combined its desired facts with idiosyncratic, handmade animation and some of the catchiest, grooviest tunes written to make essential pieces of helpful television content.

These musical numbers came from luminaries like jazz pianist Bob Dorough and musical theater composers Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty, and just about all of them are helpful earworms that genuinely made their viewers smarter, from "I'm Just a Bill" to "Conjunction Junction" and every song in between.

"Schoolhouse Rock!" rocks, full stop. It comes from a genuine desire to educate and uses the palpable powers of mass media not to distract or obfuscate but to clarify and welcome. It's a utilitarian, utopian ideal of what the art of communication can be used to accomplish, one that especially plays like tonic in a contemporary era suffused with the fear of information and truth.

Wonder Woman

"Wonder Woman" aired for three seasons from 1975 through 1979, representing the apotheosis of several popular modes of 1970s television storytelling.

It tied the ideas of an increase in mainstream feminism with so-called "jiggle television," taking the more "low-class" female-body-centric pleasures of '70s action peers like "Charlie's Angels" (a franchise which has become an accidental ode to feminism) and tying it to not one, but two genuine feminist icons: Wonder Woman herself, and Lynda Carter, the actor who portrayed her with dignity, strength, and yes, sex appeal.

The '70s also featured lots of primetime pulp, both explicitly within the burgeoning superhero genre ("The Incredible Hulk") and playing more broadly with action/sci-fi/adventure genre tropes ("The Six Million Dollar Man"). "Wonder Woman" is, obviously, a superhero action show, one that took a step forward toward the widespread acceptance of serialized, comic book storytelling on the tube while still hitting casual viewers with the clarity of episodic thrills.

"Wonder Woman" tends to clear the bar set by its peers, remaining a benchmark of culture because of its crafty ability to synthesize and disseminate so many needs and wants into a digestible program. It's all things to all people, opening the doors for so many people who never thought they were welcome in the first place.

Sesame Street

And now, another essential piece of children's entertainment, one that moved past "the facts of life" to deliver important messages on empathy and understanding, all with the art of puppets and people living together. Sorry – Muppets and people. Important distinction.

"Sesame Street" debuted in 1969 and became a phenomenon throughout the 1970s as it aired on public television. Jim Henson's Muppets, featuring beloved characters like Big Bird, Bert, Ernie, and Oscar the Grouch, lived on the same street as human children and helpful adults. Through their proximity and sneakily positive valuation of "living in a walkable urban community close to people you care about," everyone learned not just how letters and numbers work but how to live with and access things like emotions and public services in productive ways.

It's not an exaggeration to say "Sesame Street" worked to make its viewers better citizens of the world, and it's not an exaggeration to say it worked aspirationally to make the world better, too, especially with its longstanding emphasis on equity and inclusion in its representation and ideas.