Akira Toriyama Never Planned To Create Something Like Dragon Ball Z

Every night just before "Pokemon" aired on Filipino television, I'd see the last few moments of "Dragon Ball Z." In the show's ending credits, Goku's young son Gohan runs on top of a turning globe. Above, the coiling body of a dragon can be seen bracketed by clouds. Classic Chinese-style mountains rise in the corners of the screen. It's a fantasy of scale, a dream of being a small but determined child walking a world so big they will never see it all. The lyrics of the accompanying theme tune were filed away in my brain together with the names of every single Pokemon and the Water Country jingle. But as I dug deeper into the world of anime, I somehow never returned to "Dragon Ball Z." The show's reputation as an overlong spectacle of muscular martial artists powering up and then shooting giant beams at each other never matched with the ending credits sequence I'd found so intriguing.

Years later, I came across a feature on "Dragon Ball Z" in James Thompson's "House of 1000 Manga." This piece painted a very different picture of "Dragon Ball" and its creator, Akira Toriyama, than I had imagined. "Dragon Ball" is certainly one of the most successful anime and manga of all time. Nearly every popular action series made in Japan since the '90s bears its influence. But Toriyama's true forte was not action, but gags. Long before "Dragon Ball" changed comics forever, a twenty-something Toriyama — living with his parents in the countryside — drew his first hit comedy: "Dr. Slump."

'I just wanted the 100,000 yen prize'

In an interview with another comics legend Rumiko Takahashi, made available on the Takahashi fan site Rumic World, Akira Toriyama confesses what led him to become a comics artist. "To be honest," he says, "I just wanted the 100,000 yen prize." Toriyama had quit his job as a designer and was looking for something to do. While reading comics in a coffee shop, he came across a magazine offering a 500,000 yen prize to new artists. Toriyama worked hard to put something together, but missed the deadline. His last resort was a new monthly competition in Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine promising 100,000 yen. 100,000 was much harder to live on than 500,000, but Toriyama was broke. He didn't have a choice.

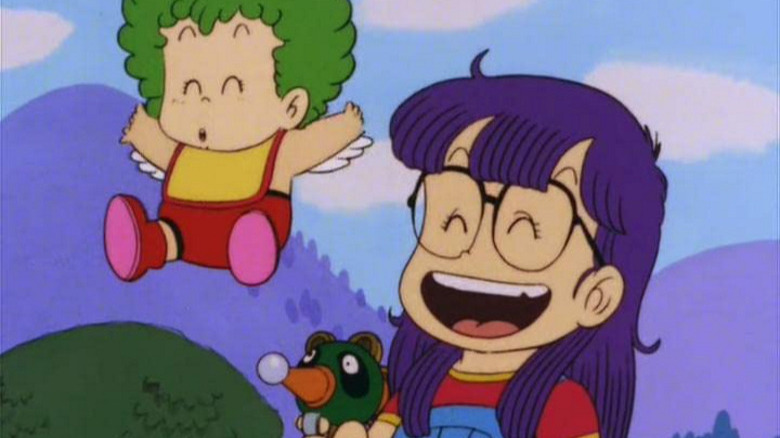

Sooner or later, Toriyama's art was seen by Shōnen Jump editor Kazuhiko Torishima. In some ways, Torishima and Toriyama were similar. Toriyama was much more familiar with Hong Kong action films and Hollywood movies than he was with contemporary manga. Meanwhile, in an interview with the Keio Times, Torishima speaks fondly of comics artists like Keiko Takemiya and Mitsuru Adachi, but confesses that few of Shōnen Jump's artists at the time did much for him. While he saw "a glimmer of talent" in Toriyama's submissions, he still rejected his output again and again. It took until 1980 for Toriyama to land his first hit: "Dr. Slump," the story of the lazy scientist Dr. Senbei and his super-strong robot daughter Arale.

Fake it 'til you make it

In an interview commemorating the 50th anniversary of Shōnen Jump, Toriyama is self-effacing about his art. Goku's blonde hair when he transforms into a Super Saiyan? "Inking his hair was such a pain." The lack of screentone? "Cutting and applying them is a pain." Toriyama is a legendary cartoonist, but he insists that his use of exaggeration was to compensate for his weaknesses as an artist. "When I first started I didn't even understand muscles or joints. As I drew, I thought, 'Aw, I'll just fake this!'" The only skill that Toriyama acknowledges that he's pretty good at is drawing animals. As a child in the countryside, he'd while away the time reading "illustrated reference books about animals, birds and fish until they [came] apart." This experience would manifest not just in "Dragon Ball" and "Dr. Slump," but in his contributions to the bestiary of the "Dragon Quest" video game series.

Toriyama's lack of formal comics training made him a perfect fit for an editor-driven magazine like Shōnen Jump. But we can't discount Toriyama's own capabilities as an artist. Manga artists typically rely on a team of assistants to help them meet deadlines. In the aforementioned interview, Toriyama's peer Takehiko Inoue says that he had a team of four assistants while working on his basketball series "Slam Dunk." By comparison, Toriyama has only ever had one at a time, and drew the initial stages of "Dr. Slump" all by himself! Toriyama may call himself a "lazy artist" all he likes, but every one of his shortcuts was necessary because there was no other way to meet his deadlines with the amount of work on his plate. Even Inoue, a legendary artist in his own right, reveres Toriyama's work.

Suppaman, not Superman

While "Dragon Ball" is the series that made Toriyama an international superstar, he is at his most creative in "Dr. Slump." The world of "Dragon Ball" aims for consistency even as it switches genres and modes. It is a grand scale adventure with (loosely defined) rules. But in "Dr. Slump," anything goes. Arale and her friends travel through time and space. They smash through borders between panels and joke about living in a manga world. Arale's home of Penguin Village hosts talking animals, dinosaurs and even Suppaman (but not Superman! Suppaman is named for pickled plums). Not to mention enough poop jokes to make Captain Underpants blush. It's a non-stop barrage of robots and pop culture references and crude sex jokes, spiralling further out of control with each chapter. Readers in Japan loved it.

But Toriyama's editors at Shōnen Jump figured that he could create something even more popular. Torishima notes in an interview that Toriyama "has great spatial awareness," superior to fellow artists like Tetsuo Hara. If he could shift gears from gags to action, Torishima thought, they might really have something. Toriyama responded with "Dragon Ball," which swapped the little robot girl Arale for a little monkey boy named Goku. The early volumes of the series combine "Dr. Slump" style goofs and Jackie Chan style action chops. But as the series continues, the gags were phased out in favor of training montages and intense action. The carefree adventure of "Dragon Ball" became the dramatics of "Dragon Ball Z."

The legend of Arale

Even "Dragon Ball Z" never quite lost the spirit that animated "Dr. Slump." As Jason Thompson said in "House of 1000 Manga," "the first great thing about Dragon Ball is that it's an action manga drawn by a gag manga artist." The storyboarding and visual jokes Toriyama pioneered in "Dr. Slump" are used to great effect throughout "Dragon Ball." The early volumes have plenty of fantastic animals and machines, and even the serious storylines that come later benefited from Toriyama's love of thwarting the reader's expectations. But over time, entropy began to set in. The power scaling of the battles escalates to such a degree that many of Goku's friends become obsolete. The end of the comic is less a grand finale than a contractual obligation. The anime adaptation is even more bloated, a consequence of its airing during the comic's serialization. (An edited version titled "Dragon Ball Z Kai" is far more watchable, and the recommended way to experience the story.)

Most Shōnen Jump artists today take lessons from "Dragon Ball" instead of "Dr. Slump." Only "One Piece" does justice to Toriyama's absurd sense of humor, and "One Piece" is a far more disciplined work than "Dragon Ball" ever was. The young, anything-goes Toriyama has been thoroughly displaced in Japan and abroad by Toriyama the commercial artist. But then, it is rumored that the "Dr. Slump" anime is what paved the way for the success of Shōnen Jump comics on television. Goku and his friends might never have hit the big time without the help of a little robot girl named Arale smiling and holding a piece of poop. A young Toriyama living with his parents in the countryside, drawing comics nonstop just to afford groceries, might have found that pretty funny.