Stephen Sondheim Projects That Never Saw The Light Of Day

When Stephen Sondheim died at age 91, the celebrated lyricist-composer left behind a bevy of classic musicals and contributions to movies as well as several unfinished, abandoned, and rejected projects. As he defied the conventions of commercial musicals, Sondheim left an indelible mark on theatre. Naturally, Sondheim's unfinished projects and incomplete concepts have attracted much interest from fans of both musical theatre and film.

While we'll omit Sondheim's unfinished final musical, "Square One," we'll examine the two volumes of his "Collected Lyrics" ("Finishing the Hat" and "Look, I Made a Hat") and quote his commentary, biography, and other sources to dive into his major and minor unrealized projects and collaborations, including unproduced stage musicals written in college, murder mysteries, a Bertolt Brecht project gone awry, shelved movies, the "Into the Woods" CD-ROM game, and a Jim Henson musical adaptation. These are the Stephen Sondheim projects that never saw the light of day.

High Tor

As chronicled in "Finishing the Hat," Stephen Sondheim's mentor and "artistic father" figure, lyricist Oscar Hammerstein, assigned Sondheim's four writing exercises. The first exercise: Take a play you like and turn it into a musical. The result was "All That Glitters," based on George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly's "Beggar on Horseback," which was staged at Williams College with Kaufman's permission.

Then the second exercise: musicalize a play he liked but thought had flaws. Sondheim chose Maxwell Anderson's verse play "High Tor." This experience taught him to cut extraneous material and form structure. However, when Sondheim wrote to Anderson for permission to have "High Tor" staged and performed, Anderson refused because the playwright was already planning his own musical version. Regarded as the first recognized made-for-TV movie, "High Tor," a love story about a stranded mortal and a ghost girl on a mountain, was broadcast in 1956 with music by Arthur Schwartz and lyrics by Anderson. It starred Bing Crosby and Julie Andrews.

Mary Poppins

Oscar Hammerstein's third exercise for Sondheim was to write a musical based on an existing novel or short story not previously dramatized. So an 18-year-old Sondheim chose "The Mary Poppins" book series by P. L. Travers (unrelated to the Disney 1964 movie adaptation with the Sherman Brothers' music and lyrics).

Though Sondheim completed two-thirds of the work and wrote three songs, he couldn't find a solid foundation through the vignettes. In "Finishing the Hat," Sondheim writes, "I couldn't figure out how to make disparate episodes hang together dramatically, even though they involved the same characters (neither could Disney)." The Disney "Mary Poppins" movie would branch out with its own musical stage adaptation in 2006.

As detailed in Meryle Secrest's "Stephen Sondheim: A Life," Travers called Sondheim in 1995 to ask him to adapt her books into a musical. She assured him that she — not Disney — had control over the rights. He astonished her by informing her that he did write songs for "Mary Poppins" when he was young. Although Sondheim lost interest in adapting "Mary Poppins," he promised Travers that he would visit her in England and was saddened that she died in 1996 before they could have tea.

Climb High

Oscar Hammerstein's fourth and final exercise would task Stephen Sondheim with writing a musical of his devising. Sondheim crafted "Climb High." In "Finishing the Hat," Sondheim calls "Climb High," a "a four-hour summation of my views on life, ambition, morality, theater and art, with a passing swipe at love" Finishing it after graduating college, Sondheim expressed his "high and foolish" hopes for a Broadway production, but he became too busy earning a living writing for the television series "Topper."

None of Sondheim's Hammerstein-assigned musicals ascended into his professional oeuvre. Produced in a college setting, "All That Glitters" came closest. Regardless of their shortcomings, the Hammerstein-assigned musicals equipped Sondheim with a portfolio that he could audition in the professional songwriting business. It led to his connection with playwright Julius J. Epstein, his collaborator on "Saturday Night." Ironically, the scheduled 1955 Broadway debut of "Saturday Night" was thwarted by its producer's death. "Saturday Night" was not staged until over four decades later.

Funny Girl

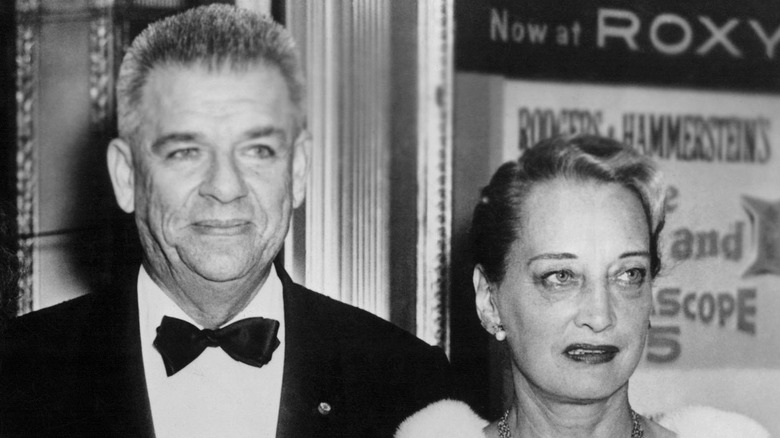

Theodore Taylor's biography, "Jule: The Story of Composer Jule Styne," shares the making of the biopic project about comedian Fanny Brice. Actress Mary Martin, the Rodgers and Hammerstein muse who suggested the idea that Brice's life could be made into a stage musical, was set to star as Brice.

Fresh out of their collaboration on "Gypsy," Styne and Sondheim were eyed to do the music and lyrics for Brice's fictionalized rise in showbiz. Although Sondheim was part of the meeting, he turned down the project. Sondheim admired Martin's character work but critiqued the casting choice. "She's not Jewish. You need someone ethnic for the part ... This is East Side New York and [Martin] can't do it." Styne speculated that Sondheim would have stayed had actress Anne Bancroft been the first pick as Brice.

Martin ended up leaving the project and second-pick Bancroft's vocal range was unsuitable. Bob Merrill handled the lyrics. The "Funny Girl" musical found its comic leading lady in Barbra Streisand, and it debuted on Broadway in 1964. Streisand would reprise her role in the 1968 film adaptation.

Sunset Boulevard

In the 1950 film, "Sunset Boulevard," washed-up movie star Norma Desmond takes in a stranded screenwriter and plots her comeback. Stephen Sondheim outlined a musical adaptation. Then, he ended up at a cocktail party with Billy Wilder, the director of the original film. Sondheim shares, "I shyly advanced the proposition [of the musical adaptation]." Wilder thought a stage adaptation more suited to the operatic form than musical theatre, explaining, "After all, it's about a dethroned queen." Sondheim agreed. Eventually, Sondheim turned down Hal Prince and Hugh Wheeler's attempt to write a musical film of "Sunset Boulevard" for Angela Lansbury.

When Sondheim divulged his encounter with Wilder, Hal Prince gave the same suggestion of doing an opera. But Sondheim had complicated feelings about writing an opera. "I don't like opera, but I have a feeling that I wish I did" he shared with senior musical specialist Mark Eden Horowitz in "Sondheim On Music." For him, opera was "too full of longueurs and recitative," while musical theatre allowed him the freedom to make cuts.

Andrew Lloyd Webber, the composer best known for "Cats" and "Phantom of the Opera," would eventually compose a "Sunset Boulevard" musical with lyrics by Don Black and Christopher Hampton. It premiered on the West End in 1993.

Murder Mysteries with Anthony Perkins

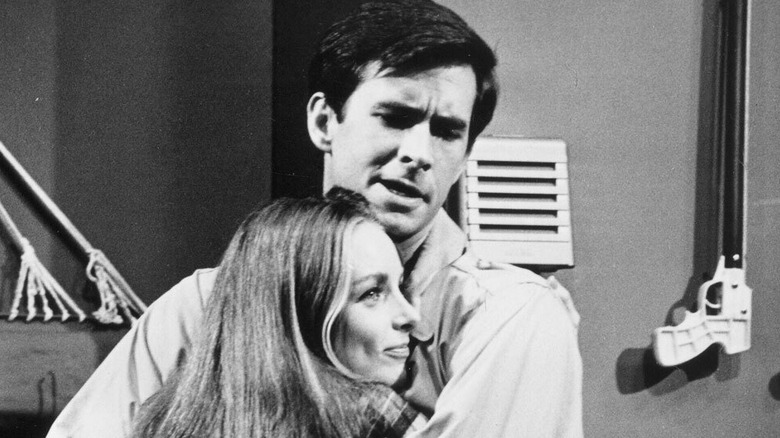

The friendship between actor Anthony Perkins (who starred in Sondheim's "Twilight Zone"-esque made-for-TV musical "Evening Primrose") and Sondheim is well-documented in Charles Winecoff's "Split Image: The Life of Anthony Perkins." True to Sondheim's passion for mystery, he and the man famous for playing Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho" would collaborate in the crime genre — and subject party guests to city-wide scavenger hunts. Sondheim and Perkins collaborated on 1973's "The Last of Sheila," revolving around the hit-and-run murder of a Hollywood producer's wife.

Two projects did not get produced. Sondheim and Perkins drafted a treatment for "The Chorus Girl Murders," a 1940s musical mystery with choreographer-director Michael Bennett (director of "A Chorus Line") as an intended vehicle for actor, singer, dancer Tommy Tune. Their other unproduced project was "Crime and Variations," which Sondheim stressed had no songs. The 75-page outline follows an unsolved crime revealed through multiple points-of-views across six episodes.

All Together Now with Terrence McNally

In the Spring 2011 issue of The Sondheim Review, the article "Mutual Admiration" reported on the might-have-been collaboration with playwright Terrence McNally. Stephen Sondheim and McNally, famous for satirically dark plays, churned through a structurally ambitious premise. However, conflicting schedules prevented the duo from completing their project.

"All Together Now" chronicles the affair between a 30-something sculptress and a young, sexy restaurateur. The story focuses on the postures that lovers adopt when feeling discomfort and its consequences. McNally said that Sondheim wanted to tell the relationship "from the present back to the moment when the couple first met." The concept dramatizes the various "Selves" of the couple as they mingle and interact. In brainstorming, McNally suggested that the Selves sing the same song at different points and then swap different musical idioms through different variations. The pair debated replaying scenes but swapping out perspectives, exploring misunderstandings, and achieving different outcomes. Their concept notes are archived at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center in Austin, Texas.

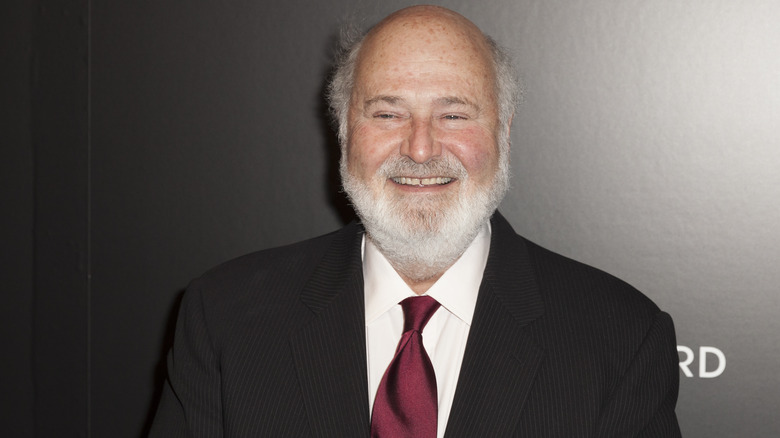

Singing Out Loud movie musical with Rob Reiner

Featuring a screenplay by William Goldman ("Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid"), "Singing Out Loud" was another musical movie project that died. It would have been Sondheim's first major original musical for the big screen.

Sondheim and Goldman contemplated on a "Company" movie adaptation but were talked out of it and moved on to "Singing Out Loud," which Rob Reiner was supposed to direct. But the film never got made. Meryle Secrest's biography, "Stephen Sondheim: A Life," quotes Rob Reiner as hailing the process as one of his greatest creative experiences. The "Stand By Me" director optimistically notes, "These things never completely die, and it may be resurrected."

However, there is video of Liza Minnelli and Billy Stritch singing one of its songs, "Water Under the Bridge." Minnelli introduces it as a new Sondheim song for a "forthcoming" movie. It is not surprising the number was to be set in a recording studio, supposedly in a moment in which the heroine lacks the confidence to sing. It stands apart from Sondheim's customary songs since it's his language blended with a contemporary pop style.

A Pray by Blecht

Any Sondheim scholar will iterate that Sondheim was not fond of the work of German playwright Bertolt Brecht. The lyricist-composer found Brecht's plays too polemical and turned down an offer to translate Brecht's Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny." But Sondheim got majorly involved in Jerome Robbins's (the choreographer and director of "West Side Story") desire to adapt the Brecht play "The Exception and the Rule" in 1968 when the musical bookwriter John Guare was recruited.

Guare conceived a reimagining where class paranoia is paired with anti-Black racism–the leading merchant, Zero Mostel was announced as the lead, was white and the guide and porter were both Black. The theatricality set the musical within a television studio. Composer Leonard Bernstein got involved. However, when Guare asked why Sondheim hadn't worked with Bernstein since "West Side Story," Sondheim's response was "You'll see." The experience and scheduling turned out to be nightmarish as accounted in Meryle Secrest's biography of Sondheim: Bernstein worked at midnight and Robbins worked in the morning.

A premiere date was set. Then Robbins walked away from the project—literally. He simply left the audition room, slipped into a taxi, and drove off to the airport. Guare, Bernstein, and Sondheim were collectively relieved. Sondheim professed shame about the project—"arch and didactic in the worst way"—and he turned away Robbins and Bernstein's subsequent attempt to revive the project 18 years later.

Into The Woods CD-ROM game

When Stephen Sondheim died, theatre fans circulated this cool bit of trivia on social media: After the failure of his highly personal 1981 project, "Merrily We Roll Along," Sondheim wanted to take a break from theatre and create video games. As detailed in the "Six by Sondheim" documentary, he was a lover of games and puzzles.

Sondheim found renewed success after "Merrily We Roll Along," and the composer did attempt to dabble in video games with "Into The Woods." The fairy tale mash-up was to be adapted as a CD-ROM game intended to teach music to kids and adult players. As Entertainment Weekly reported in 1994, the game was pending permission from Columbia Pictures. Sondheim felt "Into the Woods" had a built-in game in the plot since his main characters go on a quest. After all, the musical chronicles the chaotic hunt for "the cow as white as milk, the cape as red as blood, the hair as yellow as corn, the slipper as pure as gold." "There's nothing to solve in "Guys and Dolls" or "Oklahoma!" except who's going to take Laurey to the picnic," Sondheim joked. How this quest would have been integrated with music education is fascinating. Unfortunately, the game was never produced.

Groundhog Day musical

Considering his affinity for time-warpy musical projects like "Merrily We Roll Along," it's easy to see why Stephen Sondheim would be hooked on the idea of writing music for a misanthropic weatherman doomed to endlessly repeat the same day in a small town. Sondheim was a fan of Harold Ramis' 1993 comedy, "Groundhog Day," and considered adapting it into a musical. Though he ruled that touching Ramis' classic would "gild the lily. It cannot be improved." In addition, he felt he could replicate but not inhabit the contemporary style suited for the premise: "I could imitate contemporary music, but it's not in my gut," he confessed to Mark Eden Horowitz in the second edition of "Sondheim on Music."

Comedian Tim Minchin (famous for "Matilda the Musical") would go on to do the lyrics and music for the stage musical version of "Groundhog Day," which premiered in London in 2016 before moving to Broadway the following year. Minchin shared that Sondheim gave his blessing to the project.

Project with one of South Park's creators

Sondheim was a dedicated letter writer. "South Park" and "The Book of Mormon" creator, Trey Parker, divulged that Sondheim sent him letters, including one that praised "South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut" as a favorite before a subsequent one that praised "Team America" as usurping the former. When Sondheim's passed away, "The Book of Mormon" official Twitter account tweeted Sondheim's letter to Parker. Sondheim's letter consoled Parker for the negative critical reception of "Team America" and professed, "[I] voted for it as the best movie of the year (a fat lot of good it did you)." It also offered, "Would you ever be interested in writing a stage musical with an old traditionalist, namely me?" Sadly, we'll never know what Sondheim and Parker might have cooked up.

In their trademark crudeness, Parker and collaborator Matt Stone lampooned Sondheim in the Season 15 "South Park" episode, "Broadway Bro Down," which depicts him and high-profile Broadway composers Stephen Schwartz, Andrew Lloyd Webber, and Elton John, as beer-loving jersey-wearing men who loaded their musicals with "subtextual" lyrics to charm women into sexual favors.

Being There

Nathan Lane is a frequent star in Stephen Sondheim productions. Lane, who is also a talented writer, updated and expanded Sondheim's "The Frogs" for its 2004 revival. In an installment of Criterion's "Closet Picks," Lane revealed that he once approached Sondheim for a project based on the 1979 Hal Ashby film, "Being There."

They seemed to have disagreed on the main character's potential functionality in a musical. According to Lane, Sondheim found the main character Chance to be too much of a "cipher" and therefore would not believably express himself through song. Lane argued that was interesting enough in itself, stating, "I know, but it forces other people to sing at him ... With a character like this, I wouldn't have to sing for a while." Lane goes on to describe his vision for a showstopping first act closer. It's unknown whether Lane and Sondheim had any further discussion about this concept.

Projects with James Lapine

Sondheim turned down a suggestion to adapt Nathanael West's novel "A Cool Million" with James Lapine. At the time, Sondheim was disappointed with "Merrily" closing and wanted to take a break from collaborating with Hal Prince. Sondheim deemed "A Cool Million" too similar to the "Candide" musical adaptation, of which he contributed lyrics to in its 1973 revival, to be a fresh musical concept. The novel itself is self-described as a "The Dismantling of Lemuel Pitkin" just as Voltaire repudiated philosophical optimists. Lapine and Sondheim would go on to birth "Sunday In the Park With George" and they would work on "Into the Woods," "Passion," and other projects.

What physical rhymes would Sondheim flex for the subject of bodybuilding? Had Lapine and Sondheim weight-lifted further into project "Muscle," we would have known. In the concept for "Muscle," based on the memoir of Sam Fussell, a young intellectual becomes obsessed with bodybuilding and withdraws from the world to commit to it. "Muscle" was intended to be paired with the one-act musical "Passion," a Lapine-Sondheim collaboration. Though "Passion" evolved to have a longer running time and Sondheim eventually didn't feel suited to do "Muscle." Lapine took "Muscle" to composer William Finn and lyricist Ellen Fitzhugh and this "Muscle" got its staging in Chicago in 2001.

Into the Woods with the Jim Henson Company

Consider a Jim Henson-crafted "Into the Woods" movie a pop-culture White Whale. Sondheim shared that Henson was going to be involved with the "Into the Woods" film adaptation. Henson Productions would design the animal puppets to perform alongside actors. This film adaptation might have starred Robin Williams as the Baker. A table read also involved Cher as the Witch, Goldie Hawn as the Baker's Wife, Steve Martin as the Wolf, and Danny DeVito as the Giant. Following Henson's death in 1990, Henson Productions remained committed to co-produce the movie with Columbia Pictures, but the project never surfaced.

An early draft of this "Into the Woods" was different from the completed 2014 Disney-produced version that Rob Marshall directed. For example, the Baker's Wife fakes her death and turns up unscathed at the end. Sondheim noted that the moving number "Children Will Listen" had yet to be worked into the draft. At this point, you're probably craving concept art, but none has ever been released.

Other unrealized projects

"How Sondheim Found His Sound" chronologically catalogs abandoned and unproduced projects. Meryle Secrest's "Stephen Sondheim: A Life" expands on a few interesting ones. A 1954 project, "The Lady or the Tiger," was a fable about an ancient king who had an unconventional sentencing method. A prisoner must choose between two doors. The right door grants the prisoner a beautiful bride. The wrong door gets them gobbled up by a tiger.

Stephen Sondheim was also involved in the unproduced 1956 project, "The Last Resorts." Inspired by Cleveland Amory's bestselling book, "The Last Resorts" follows a journalist who travels to Florida to report on the visiting Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Hal Prince had creative disagreements with Jean Kerr's script. Prince said the conflict festered when "Steve broke through that there was a great reluctance to appreciate the nature of his talent."

In the unfinished musical, "The Jet-Propelled Couch," a psychiatrist encounters a patient who retreats into an outer space fantasy. The psychiatrist decides to involve himself in that fantasy.