The 39 Best Spy Movies Of All Time

In a 1956 letter to noir legend Raymond Chandler, Ian Fleming referred to his James Bond novels as "pillow fantasies of the bang-bang, kiss-kiss variety." The phrase would eventually be turned around and immortalized as hepcat slang for spy cinema around the world. The business of kiss kiss, bang bang has been booming ever since. Fleming's creation for Queen and Country is now the second-longest running franchise in film history. "Mission: Impossible" has been playing in theaters longer than it ever aired on TV. Every few years, a new parody takes aim at the espionage du jour — "Austin Powers," "OSS 117," "Kingsman" — and invariably spawns its own ongoing franchise.

Spies and movies were made for one another. So long as there are international incidents, audiences will line up to watch fictional people prevent them. Factions rearrange their acronyms. Frictions boil over into bureaucratic friendships. But secrets, suspense, and intimacy never go out of style, and neither have these 35 films.

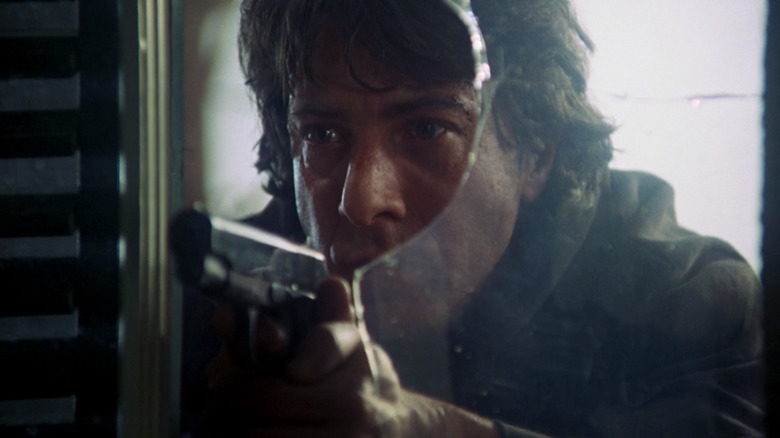

Marathon Man

"Marathon Man" begins with hypnosis, but not the kind that shows up later on this list. This kind only affects the audience. In October 1976, they'd never seen anything like it. "Bound for Glory" was the first film to use the Steadicam system, but "Marathon Man" beat it to theaters by two months. Dustin Hoffman debuted it at jogging speed. The serenity is uncanny. Before a word is said, everything is wrong.

But Hoffman's Babe doesn't know any better. He can sleep easy knowing his big brother, Doc (Roy Scheider), is a run-of-the-mill businessman. In just a few short days, though, he'll become intimately acquainted with the investment potential of war crimes and the dangers of incompetent dentistry. Like the novel from screenwriting great William Goldman, "Marathon Man" tangles and unravels but marches on with the grim inevitability of rising water in a locked room. By the end, viewers gasp on Hoffman's behalf. By the time Sir Laurence Olivier asks his infamous question — "Is it safe?" — the audience breaks for him.

The Hunt for Red October

Just as President John F. Kennedy unofficially christened Ian Fleming the spymaster-in-chief, so Ronald Reagan anointed Tom Clancy, turning the insurance salesman into a best-selling novelist overnight.

"The Hunt for Red October" is a miracle of economy. It's not short, running 135 minutes from tip to tail. Much of Clancy's tech-manual plotting about "caterpillar drives" and "Crazy Ivans" survives intact. And yet, in the distillation from hardcover doorstop to fifth highest-grossing blockbuster of 1990, it improved. The script from Larry Ferguson and Donald E. Stewart streamlines Clancy's story into one long zoom, starting wide with meetings in the halls of power and ending tight on an accountant trading potshots with a Russian traitor between nuclear missiles.

Director John McTiernan and cinematographer Jan de Bont, reuniting from "Die Hard," weaponize the anamorphic sweep. Early on, when boy scout Alec Baldwin inspects a submarine under construction, nothing has ever looked bigger. By the end, faces loom larger, spelling panic only in wrinkles. No Clancy adaptation yet has matched it. None have had a performance like Sean Connery's, either.

Mission: Impossible

First-time producer Tom Cruise met Brian De Palma by accident during a fortuitous dinner at Steven Spielberg's house. That night, he hosted his own 14-hour De Palma film festival.

For "Mission: Impossible," there was no second choice. Among blockbusters, "Mission: Impossible" is the perfect marriage of art and artist. For all the exploding sticks of chewing gum and rubber Jon Voights, De Palma is the handiest gadget of all. He opens the film on one agent (Emilio Estevez) watching another (Cruise) carry out a real interrogation in a fake interrogation room. It's a warning. On a good day, this is a world of illusion. On the rest, it's a place where Three-card Monte dealers try to con each other.

The genuine tricks play straight. Close-up magic with an all-important disc. Hunt catching himself inches above a pressure-sensitive floor. Everything else is machine-tooled to make you feel the clandestine gibberish more than follow it. De Palma knew what he was doing; to date, he considers the one-two punch of "Carlito's Way" and "Mission: Impossible" the pinnacle of his career.

Spy Game

At the end of a folksy story about a veterinarian who offered to put down his uncle's plow horse, retiring CIA agent Robert Redford comes to a cold point: "Why would I ask somebody else to kill a horse that belonged to me?"

Like every line in "Spy Game," it reads at least two different ways, neither definitive, both useless on the record. This is the native tongue of intelligence — a willful lack thereof. All the suits gathered for Redford's last-day-on-the-job interrogation speak nothing else. In the field, like the Chinese prison where apprentice Brad Pitt rots, that language is about as useful as a party trick. That leaves Redford to negotiate his protégé's freedom while simultaneously denying it to his superiors, who'd just as soon disavow their prize thoroughbred.

It's dizzying by design. "Spy Game" is the first fully-formed example of director Tony Scott's late style. Scenes aren't shot so much as strafed — the use of helicopters to film a personal rooftop conversation confused Redford until the premiere.

Murderers' Row

Before Austin Powers and even our man Flint, there was Matt Helm. The character originated in a series of novels with 27 installments by author Donald Hamilton. Beyond the titles, none of those matter. As much as any role ever has been, the cinematic Helm is defined by its originator. Matt Helm was Dean Martin.

In this, his second of four on-screen misadventures, Matt Helm receives orders from a tape recorder hidden in a bottle of Irish whiskey he instinctively opens while driving. That's as potent a mission statement as any for the Matt Helm saga. He's charged with stopping maniac-of-the-week Karl Malden, who wants to aim a magnifying glass at Washington. It's just an excuse for Dino to charm his way across the French Riviera — studio sets built to match — drop innuendo around his latest costar — Ann-Margret, incandescent — and fiddle with a comically impractical gadget — a delayed-trigger pistol that assumes all evildoers will stare down the barrel to check if it's loaded.

In Helm's world, they always do.

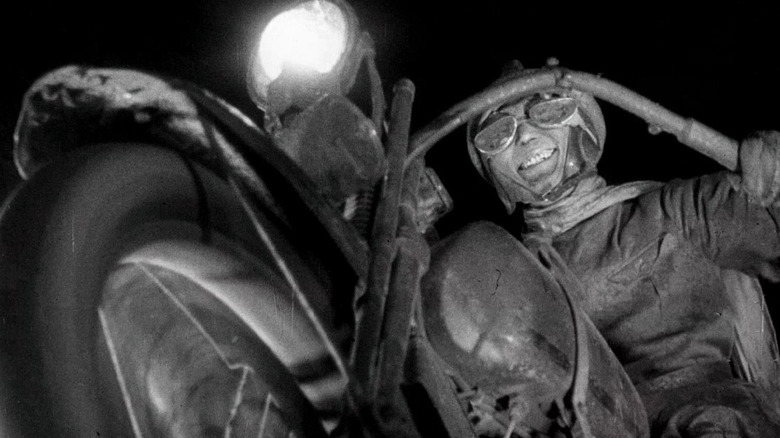

Spies

There's an early subtitle in Fritz Lang's "Spies" that, depending on the translation, carves the genre down to its very marrow: "Important documents have disappeared!"

The film is as universal as its namesake, though that may have been in self-defense; Lang was forced into making a crowd-pleaser after the financial disaster of his magnum opus, "Metropolis." But in trying to sell popcorn, Lang minted dozens of spy clichés wholesale. A square-jawed man of action known only by his agency number — 326, in this case. White-knuckle set pieces rolling into each other, with the hero only needing a brush-off between an astounding train crash and an impressive motorcycle chase. The supervillain-as-puppeteer, a goateed vision of evil shrouded in ambiguous smoke.

The only innovation that hasn't been Xeroxed into oblivion is an omniscient focus on the evildoer. Rudolf Klein-Rogge's Haghi is the star of the show. For all it inspired as the spy film primordial, "Spies" shows much more patience for the outlaw and, in the inevitable end, maybe even sympathy.

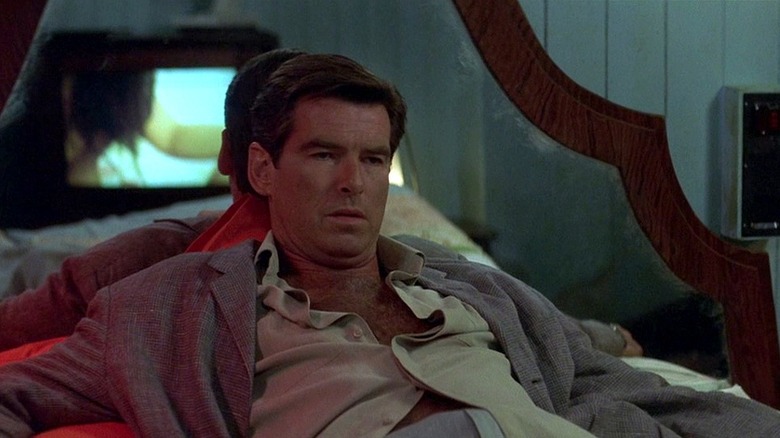

The Tailor of Panama

James Bond is a fantasy. Andy Osnard is a byproduct, a flesh-and-blood sexual harassment case on Her Majesty's secret service, hiding as far from Her Majesty as diplomatically possible. It's an underappreciated casting coup that Osnard happened to be played by the sitting Bond.

Pierce Brosnan seems more at home with the dirty spycraft of John le Carré than he ever was with Ian Fleming's jet-setting. When Osnard blackmails presidential tailor Harry Pendel (Geoffrey Rush) into feeding him information, it sounds like a timeshare presentation. When he finds out that Pendel is making the intel up, it sounds like a dream — less work for ol' Andy Osnard if the rumored revolution stumbles before the starting line.

This isn't the most potent dose of le Carré's pencils-down pessimism, where frantic pawns are sacrificed to the strategy of men continents away from the frontlines. Panama isn't a frontline, and Osnard isn't a pawn — he's just a loser looking for a picturesque place to die.

Spy

Judged solely on its title, Paul Feig's 2015 movie "Spy" is a shoo-in for this list. Thankfully, the quality of the movie actually makes it worthy of inclusion on several other merits, including (but not limited to) the amount of spy craft happening during its runtime. Feig brings out the best in star Melissa McCarthy, who plays a CIA desk jockey named Susan Cooper who's spent her career serving as the remote eyes and ears of a suave, idiotic spy played by Jude Law. But when a list of the agency's field agents falls into the wrong hands, Cooper becomes the perfect choice to get it back precisely because the enemy will never suspect her — she's a middle-aged woman who's never been in the field herself. That scenario results in all sorts of zany antics, but unlike most Melissa McCarthy comedies (which, to be completely frank, are frequently terrible), these antics are actually extremely enjoyable to watch.

McCarthy is terrific as the highly competent but underestimated lead character, Law is great as the dumb field agent, and Rose Byrne is delightful as an over-the-top villain, but shockingly, it's Jason Statham who walks away with the movie by delivering the funniest performance of his career. He's pitch-perfect here, full of sexism and blustering bravado, and his foul-mouthed juxtaposition with McCarthy's innocent operative gives the movie a pleasant familiarity. There's plenty of spy work packed in, from characters adopting fake personas to trying to stop the sale of a nuclear bomb, but the comedy rightfully takes a front seat, and Feig and his collaborators are so dialed in that they nail every aspect of this story. Action-packed and consistently hilarious, I'm convinced Spy is not just one of the best spy movies of this century, but one of the best action comedies of all time. (Ben Pearson)

The Bourne Identity

After "Swingers" and "Go", director Doug Liman wanted to make a James Bond movie but knew he was too green and too American to land the gig. Instead, he turned to an old favorite by Robert Ludlum.

Jason Bourne wakes up with no past, save a few concerningly violent skills. What Bourne he does have, however, is plenty of style. With cinematographer Oliver Wood and a script from soon-to-be franchise steward Tony Gilroy, Liman knocked the genre off its tripod. Every fistfight is a life-or-death struggle, the camera abandoning traditional coverage to dodge punches alongside the hero. Every chase is shot low and close, as if exclusively watched by innocent bystanders and rattled passengers. The effect is aggressive and grounding — the audience is always as frenzied as the world's most wanted man.

Liman's experimental directing style, requiring four rounds of reshoots, cost him a franchise but earned him a roundabout legacy — Bond took obvious notes for "Casino Royale."

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Espionage is a glorified game of pretend. Just look at the title of "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy," strung together from the codenames of an intelligence agency known as "The Circus." These are government employees in their finest tweeds playing chess in a room with all the charm of a microwave oven.

John le Carré's spy games are won on sustained precision — knowing just as little as the enemy, but maintaining the stiff upper lip until they flinch first. Director Tomas Alfredson channels that agonizing stillness into every scene, and Gary Oldman, taking up the spectacles as le Carré's most famous creation, pushes it even farther.

George Smiley is the ugliest duckling in a department staffed by nothing but, unremarkable to the point of invisibility and seemingly immobile, but endlessly churning underneath. His inquiries land with the impregnable force of an insurance investigator, his silences with the self-destructive courtesy of a priest awaiting confession. What makes Smiley, Oldman's performance, and the film itself an all-timer is his drunkenly revealed philosophy: the only moral difference between him and his quarry is the quaint codename.

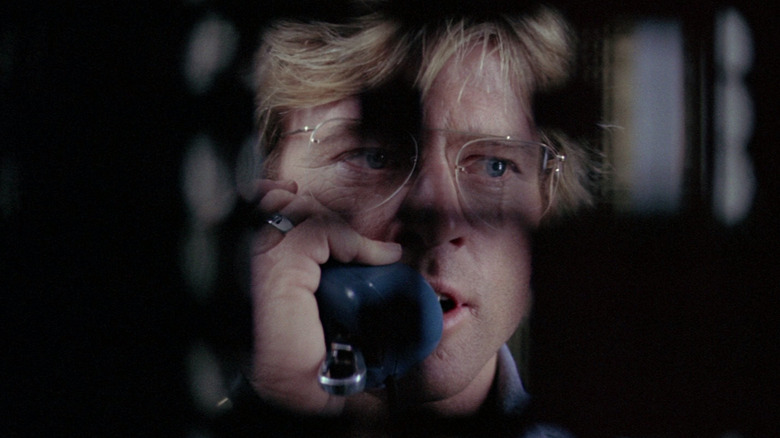

3 Days of the Condor

"What is it with you people?" asks unlucky CIA analyst Robert Redford, somewhere near the end of his rope. "You think not getting caught in a lie is the same as telling the truth." It took him long enough to learn.

Joe Turner spends his days poring over paperbacks and doctor's office magazines in the statistically impossible chance they contain coded threats against the American Way. Aflutter with his latest goose chase, Turner picks up lunch. While he's out, the rest of the office is gunned down in a bloody haze.

"3 Days of the Condor," already winnowed down from the original novel's six, is a masterclass of focus. Turner has been dragged into a completely plausible conspiracy. He's the latest pin on a corkboard already tangled with yarn. It's impossible for him to ever see the whole weave. He bluffs that nobody else can either. The ending, almost supernatural in its calm, remains one of the most chilling in spy cinema.

North by Northwest

Screenwriter Ernest Lehman pitched the possibility of "North by Northwest" to its director in the purest way it has ever been described: "The Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures." It started as a disparate collection of doodles the legendary filmmaker couldn't fit anywhere else. A murder at the United Nations. A foot chase across Mount Rushmore. This creative process would become SOP for blockbusters — it's how each "Mission: Impossible" is made – but was unheard of at the time.

New York ad man Roger Thornhill, dangerous only in charm, is mistaken for George Kaplan, somebody dangerous enough for very powerful people to want him dead. Seeing no way out but through, Thornhill decides to scour the country for the real Kaplan to prove his innocence. His foolhardy crusade leaves him framed for the murder of a foreign dignitary, accosted by a crop duster, and dangling off a former president's face.

What holds "North by Northwest" together are the combined star powers of Cary Grant and Eve Saint Marie, beautiful people in beautiful peril. Anyone too concerned about the grinding of gears is given one of cinema's finest kiss-offs — all unnecessary exposition is drowned out by an airplane engine.

The Ipcress File

Just six months after "Goldfinger" and nine before "Thunderball," James Bond co-producer Harry Saltzman put out a much less exotic alternative for audiences burned out on ejector seats and high adventure. Harry Palmer, unnamed in Len Deighton's novels, longs for even low adventure. Fresh-ground coffee is his only vice. A good day at work means as little interaction with his superiors, all animatronic parodies of British heroism, as possible. Fresh air comes with a friendly reminder that he's just the office drone with the most exploitable criminal record.

As Palmer, Michael Caine takes it all like paid detention, the famed Curry & Paxton frames turning his half-awake eyes into cocky little security cameras. He doesn't think he'll get away with anything — he never has — but he knows his mission about the mysteriously reappearing scientists will get worse in ways he hasn't even begun to understand. Naturally, nightmarishly, it does.

All three of the theatrical Palmer films are worth seeking out. "Funeral in Berlin," directed by fellow Bond alum Guy Hamilton, is the nittiest and grittiest. "Billion Dollar Brain," a sore-thumb project for firebrand Ken Russell, goes disturbingly gonzo. But "Ipcress," shot alternately like a stakeout and hypnosis by Sydney J. Furie and cinematographer Otto Heller, remains the best of the bunch.

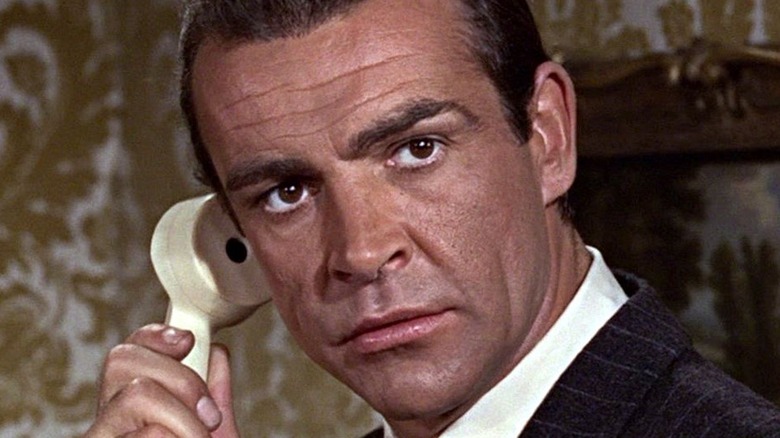

From Russia With Love

24 Bond missions later and counting, "From Russia With Love" still tops best-of lists and endures as shorthand, often by the latest creatives to take the reins, for what the world's greatest secret agent could and should be. Watched today, it's a franchise urtext, with whole characters, sequences, and subplots borrowed, budgeted up, and done over again, if rarely so well.

"From Russia With Love" traded the tropical seclusion of "Dr. No" for a European travelogue. Bond would be waging the Cold War in the trenches, with evil conglomerate SPECTRE taking the geopolitical hit. All 007 has to do is help a Russian defect with her side's bespoke decoding device. There is no threat of global domination or destruction. The most lavish gadget is a briefcase with pocket change sewn into the lining. The villains want nothing more than the untimely demise of James Bond. James Bond wants nothing more than the decoder and the conspicuously beautiful defector. This is spycraft built for speed, suspense, and shameless intercourse, as Fleming intended.

"From Russia With Love" turned James Bond from a fluke — adjusted for inflation, "Dr. No" cost less than 4% of the estimated $250 million spent on "No Time to Die" — to a franchise. "Goldfinger" brought in the pomp and circumstance the very next year. It's a matter of personal taste as to which film laid the superior groundwork, but the case could be made that neither has been surpassed since.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold

This would qualify for the gold by a monologue alone. It arrives late, at the exhausted end of an explanation. In a moment of self-loathing clarity, Richard Burton's Alec Leamas lays plain the entire Cold War to a companion not used to the same questions — do the letters you work for spell f-r-i-e-n-d – or the numb answers: today they do.

In cinematographer Oswald Morris's bleak black-and-white, only ruin shows correctly. The remains of Berlin. The crumble of a prison cell. The bags beneath Burton's eyes. Beauty muddles — a lakefront postcard view is just gray-on-gray. Leamas has kept his nose to the cobblestones too long to notice anyways. Director Martin Ritt gives him precious little chance to see anything else. Espionage here is an endless game of chicken, played until nerves are shot and, past that, bars stop serving. The only action is reaction. Leamas violates that golden rule only once, at the very end.

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery

Since 1962, spy cinema had minted no line more iconic than, "Bond, James Bond." In 1997, another British secret agent finally gave that piece of dialogue a run for its money — and with the same syntax, no less. Quoth the Austin, "Yeah, baby, yeah."

When his "Saturday Night Live" tenure came to an end in 1995, Mike Myers disappeared from everything but reruns. Two years later, he emerged from his cocoon fully-formed and shagadelic, a movie star independent of his televised past. The gonzo daring of "Austin Powers" has since been dulled by its sequels and cultural saturation, but that original leap still deserves commendation.

Instead of updating the gentleman spy for modern times, as 007 had struggled to do since Timothy Dalton's Bond swore off casual intercourse, Myers transported his free-loving creation express from 1967 into the nearly-new millennium. The outcome of the Cold War. The moon landing. Condoms. It's a rude awakening not only for the titular man of mystery, but for contemporary audiences. "Austin Powers" resurrected an archetype that hadn't been celebrated or skewered for decades, and did both so effectively that its inspiration hasn't been the same since. In a 2014 interview with MI6 Confidential Magazine, Daniel Craig put it plainly: "Mike Myers f'ed us." For "Austin," that's a big shag to brag about.

Mission: Impossible - Fallout

You might be thinking to yourself, isn't there a "Mission: Impossible" movie on this list? Yes, but that's Brian De Palma's action thriller approach to the big screen adaptation of the classic TV show. The franchise has changed drastically in the nearly 30 years it's been active, and the kind of espionage action we get in "Mission: Impossible – Fallout" from director Christopher McQuarrie is entirely different from what Tom Cruise's IMF agent Ethan Hunt went through back in 1996.

What makes "Fallout" shine are the creative and stunning setpieces that the "Mission: Impossible" series have become known for over the years. While the missions remain fairly impossible, or at least extremely difficult, the stunts at the center of them are surprisingly practical and undeniably impressive. "Fallout" has some of the most unbelievable stunts that Tom Cruise actually pulled off himself, from an intense HALO jump over Paris to a corkscrew dive in a helicopter, Cruise trained hundreds of hours in order to pull these stunts off and make them feel spectacular and realistic. That's not even including the high speed motorcycle chase or a rooftop jump where Cruise actually broke his ankle and kept on shooting.

But aside from the wild action sequences, "Fallout" also has the best story out of any of the "Mission: Impossible" sequels, providing a twisty plot that is constantly putting Ethan and his team (Simon Pegg, Ving Rhames, and a newer ally in Rebecca Ferguson) into danger. Plus, there's the addition of Henry Cavill as a cocky, meddlesome CIA agent named Walker, an arms broker and con artist known as the White Widow (Vanessa Kirby), and the surprising return of villain Solomon Lane (Sean Harris) making things even more complicated. But somehow, "Fallout" never manages to over do it, and it just might be the best entry in the franchise. (Ethan Anderton)

Casino Royale

"Die Another Day," Bond number 20, had the dual misfortunes of being the goofiest entry in the series since the Moore age and the first to be released after "The Bourne Identity." Although it made more worldwide than any previous 007 adventure, American ticket sales warned of another challenger: "Austin Powers in Goldmember" outgrossed it by $53 million. The world's greatest secret agent was officially under siege.

When he returned four years later, James Bond arrived in black-and-white. It was an audition, fictionally and otherwise. Daniel Craig sits in the dark, waiting to kill his second target and earn his double-0 stripes. When he finally pulls the trigger, he does so in cold blood, a frostbitten touch not seen since "Dr. No." His first kill interrupts, violent in both senses, with a clawed-eye ferocity never seen before in the franchise. 007, young, eternal, and soul-bruised, reporting for duty.

Director Martin Campbell's revisionist MI6 adventure, his second Bond film after "GoldenEye," puts the new guy through his brutally unprecedented paces. Parkour atop a pair of cranes in Madagascar. A poker game for the fate of a terrorist cell. The most visceral torture scene ever snuck into a PG-13. And, of course, a broken heart. There's a reason why every mission since has connected back to "Casino Royale" one way or another. Like the credits promise, James Bond did return — against all odds, in the 20th sequel, better than ever.

Casablanca

According to Aljean Harmetz's making-of account, "Round Up the Usual Suspects," the first studio notes on the play that became "Casablanca" labeled it "sheer hokum melodrama." Ordinarily, that summary would pass muster for most spy fiction. In this case, it's applied to a film so iconic that it shakes off all spy stink by the sheer force of its quality.

"Casablanca" is a romance in the same way that holy texts are literature. Saloon owner Humphrey Bogart cynically, drunkenly kills time in No Man's Land until one-that-got-away Ingrid Bergman drifts in from the fog of war on the arm of French Resistance spy Paul Henreid. Her new husband needs an escape plan that only her old flame can guarantee. Even summarizing the film feels like sacrilege, but such legend clouds the dizzying simplicity of its fundamental conflict.

With a bleary eye and busted spirit, Bogart holds the future of World War II in the palm of his hand — or, at least, the safe confines of Dooley Wilson's piano. In ways more graceful and anxious than most traditional espionage stories, the fate of humanity boils down to its smallest measurable units. The right song played at the right time. A flinch of uncharacteristic mercy. Good memories projected through a shot glass. A hill of beans, tragically, miraculously forsaken in favor of that capital-G Greater Good. So much for hokum.

The Russia House

Soon after its 1989 printing, "The Russia House" became John le Carre's first work published in the Soviet Union. That alone says almost as much as the novel itself, a story about his so-called "grey men" jumping at the last long shadows before the sun finally sets on the Cold War.

In Fred Schepisi's 1990 adaptation, the greys come in vibrant shades. CIA chief Roy Scheider, who spent most of his career ginning up arms races, finds himself wanting to believe a leaked report about inept Soviet defenses despite the fact that its veracity is annihilating his business. MI6 chief James Fox doesn't necessarily enjoy international cooperation, but believes in the documents enough to smirk and bear it. Army Colonel J.T. Walsh would execute any American not actively carrying a flag, if he could.

Stranded in the middle of their game are two civilians, a carousing publisher and a Soviet bagwoman. As the former, Sean Connery was never livelier. As the latter, Michelle Pfeiffer is as arresting as ever. Their unlikely romance unfolds as gently as the operation around them doesn't. No questions of loyalty. No surveillance-by-committee. It's glasnost on the smallest scale possible. Not that the grey men notice — they're too busy trying to play the hits.

No Way Out

In "The Big Clock," the 1946 Kenneth Fearing potboiler that was eventually reworked into "No Way Out," the apocalyptic ticking sound is contained to the relatively insulated publishing industry. An editor cheating with his boss' wife is suddenly, hopelessly entrusted to find her murderer, despite knowing the husband did it dead-to-rights. To update that fatalist tension for the thermonuclear '80s, the editor was changed to an upstart naval hero and his boss promoted to Secretary of Defense.

In "No Way Out," Lieutenant Commander Kevin Costner isn't just trying to find the scoundrel who killed his lover, Sean Young, but the legendary Russian agent who killed Sean Young. And as soon as a smoking-gun negative of them together is digitally enhanced enough for an ID, guilty party Gene Hackman can throw the full weight of the United States government at him as both a murderer and a traitor. Except the mythical "Yuri" is just that — a myth — meaning that Costner can't even sniff out the real one to take the fall.

"No Way Out" is a feature-length fuse. Every time the sublimely unlucky hero manages to outpace it, bureaucracy or fresh evidence ties his dress whites together again. The Pentagon-set finale is a powder keg for the ages, with Costner racing a dot matrix printer and evading a manhunt at the same time. There's no more thrilling artifact of the Cold War's dusk, when everyone looked like a spy if you squinted long enough.

The Manchurian Candidate (1962)

McCarthy stand-in James Gregory can't decide how many Communists he thinks are hiding out in the State Department. His wife, merciless puppet master Angela Lansbury, tells him to pick a number and get on with it. He finds the crux of his imaginary crusade on a ketchup bottle.

"The Manchurian Candidate" is as American as Heinz 57. It's the story of a red, white, and blue — but not that red — war hero, Laurence Harvey, returning to take his sainted place in line as a senator's son. His squad mates have nothing but praise for him; identical praise to the letter, in fact. One such squad mate, Frank Sinatra, starts to wonder how much choice his old friend has in the matter. It's impossible to spoil the mystery therein because, to the credit of all involved, "The Manchurian Candidate" has become spy-fi shorthand for its secret.

"We three people believed what we were doing," said Sinatra in a 1988 roundtable with director John Frankenheimer and writer-producer George Axelrod. "We wouldn't have been together if we hadn't believed it." That conviction, snowballed by the soon-after assassination of John F. Kennedy, elevates its sleeper agent pulp into conspiracy movie canon. The filmmakers pulled no punches from Richard Condon's 1959 novel. Just as impressively, neither does Jonathan Demme's 2004 remake, which turns its sights on a newer, post 9-11 American Way.

Charade

Before world-weary translator Audrey Hepburn can divorce her husband, he has good enough timing and bad enough luck to be murdered, leaving only questions in his will. Why was he fleeing the country with four passports under different names? Why did he auction off everything in their apartment before leaving? Why did the only other mourners take turns making sure that his corpse was really cold?

Overnight, Hepburn becomes the most popular American in France. CIA chief Walter Matthau wants answers. Heavies George Kennedy, James Coburn, and Ned Glass want her husband's stolen gold. And then there's that tall, dark, and possibly murderous stranger played by Cary Grant. Given that cast, that hook, and that vintage, "Charade" is often written off as Hitchcock-lite and, though it wears that half-compliment well, director Stanley Donen deserves better.

"Charade" wears its spy movie trappings like Hepburn wears Givenchy. The Technicolor action is as alluring as anything, but a stylish distraction from the real charm. Donen's thriller beats with the heart of his earlier romantic comedies. For all the assumed identities and double-crosses, one thing's never in doubt: Hepburn wants Grant at his earliest convenience. When she badgers him into showering in the same hotel room, he invites her to watch, then starts scrubbing, suit and all. Their chemistry blinds from line one, when Hepburn tells the vacationing charmer, "I already know a lot of people, and until one of them dies I couldn't possibly know anyone else." Though she speaks too soon, the incomparable pleasure is all ours.

Burn After Reading

In an interview with Uncut, the Coen brothers were asked why they made "Burn After Reading," and Joel took point: "I don't know. Honestly. We just said, 'Let's do a spy movie.'" For the characters thus invented and the audiences later confused — the absurdist comedy landed seven months after "No Country for Old Men" took home the Oscar for best picture — that answer is the punchline to a cosmic joke they were let in on too late.

This is a spy movie about people who watch too many spy movies. When personal trainers Frances McDormand and Brad Pitt discover a rough draft of forcibly retired CIA agent John Malkovich's autobiography, they mistake it for state secrets. From there on out, nobody makes moves so much as dumber, deadlier mistakes. Paranoiac lothario George Clooney kills a John Doe, then ignorantly joins the investigation into his suspected abduction. Pitt, so distracted by the imagined intrigue he refers to no more specifically than "s**t," tears a customer's glute. The dynamic duo manages to arrange a white-knuckle meeting with the KGB over information that is functionally useless to either government involved.

The operation blunders to an anti-climax blacker than a classified stamp. For anyone turned off by the bitter aftertaste, there's always "Hopscotch," with Walter Matthau weaponizing his memoirs to sillier effect.

The Day of the Jackal

The assassin known only as the Jackal takes aim at a hanging melon with a custom-built rifle small enough to hide in a hollowed-out crutch. He centers the imaginary forehead, fires, and connects four inches to the left. Holding his stance, he pulls a flathead screwdriver from his pocket and adjusts his sights. After a second shot lands an inch wide, the Jackal plugs the melon right between painted-on eyes.

Most cloak-and-dagger thrillers leave out these finer points, but "The Day of the Jackal" is built of nothing else. When hired to assassinate the French president, the legendary hitman played by Edward Fox goes about his work like a grocery list. Forge aeronautic schematics for cover identity. Buy hair dye and Old Spice bottles to disguise it for travel. Draw up specifications for the gunsmith and negotiate payment. He's just as capable in the field, too. After his car is made, the Jackal simply pulls over into the woods, hooks a paint gun to the battery, and turns it into a different car.

This is suspense by hyper-competence, an inexorable march toward that final, fateful squeeze of the trigger. There's no doubt that pigeon-keeping detective Michael Lonsdale, the Sherlock to the Jackal's Moriarty, will catch on to him. Too bad the only thing that matters in missions like these is catching up.

Top Secret!

When the filmmaking team of Jim Abrams, David Zucker, and Jerry Zucker turned themselves into a household acronym (ZAZ) with "Airplane!," they had help. Their tomfoolery was lumped onto an existing bone structure, borrowing the plot and select dialogue from the 1957 thriller "Zero Hour!" For their eagerly awaited follow-up, the team decided no such assistance was necessary. "'Airplane!' is more of a movie," explained Jerry Zucker in an interview with ScreenCrush, "and 'Top Secret!' is a little more of a joke book."

And how. "Top Secret!" is, in no particular order, a parody of teen beach movies, war movies, Elvis movies, men-on-a-mission movies, and, yes, spy movies. Though ZAZ would later regret not finding a beater to bolt their after-market outlandishness onto, this tabula rasa plotting lends "Top Secret!" something few if any other spoofs can claim: genuine suspense. Not of impending doom — the audience knows that teen heartthrob Val Kilmer can only die if it's very, very silly — but comic madness. There's just no way of guessing how they'll bring in any given scene in for a landing or, may God have mercy, top it with the next one. Underwater bar fights. Covert meetings shot backwards and played forwards. Enemy guards falling from their towers and shattering like dinner plates. A full musical number and a full music video.

By blazing its own cockeyed trail, "Top Secret!" closes the loop, leaving the distinct impression that there must be an unsung, teenybopper spy movie buried beneath the gags. But that's what makes it ZAZ's finest cinematic achievement: It's just too funny to be true.

The Parallax View

As the sour center of director Alan J. Pakula's paranoia trilogy, which began with "Klute" and ended with "All the President's Men," "The Parallax View" hasn't lost any of its bite. Not that the others could pass for candy-coating, but this film doesn't have the unlikely intimacy of the former or the righteous dot-dot-dot of the latter. Reporter Warren Beatty, a hippie aging gracelessly into a part-time rebel, is left to investigate the assassination of a presidential candidate all by his harrowing lonesome, without the promise of a happy-enough ending.

Instead, he starts in the ruins of promise, one Mad Libs sheet removed from John F. Kennedy. His search for the metaphorical grassy knoll takes him on a funhouse tour of Americana, from bar brawls in paper saloons to miniature trains that go nowhere for fun. Pakula and cinematographer Gordon Willis code an all-consuming offness into each anamorphic frame like sleeper shorthand. What Beatty discovers, deeper and darker than any who or why, is that everything is an inch out of joint, and has been for longer than his dead politician was ever alive.

What makes "The Parallax View" essential spy cinema is a single montage, the one shown to wannabe operatives looking to change the world the 50-caliber way. At first, it's disarmingly pleasant. By the end, it's a jump-cut dictionary of the American Dream. "Country" means George Washington's portrait hanging at an enemy rally. "Happiness" is Marvel Comics and big, shiny bullets. So much for the dot-dot-dot.

Sneakers

After an NSA agent reveals exactly how the organization will be blackmailing idealistic hacker turned security consultant Robert Redford into recovering a Russian gadget capable of zeroing out national economies, he cuts the tension with a smile: "We're the good guys."

"Gee," says Redford, flat as a pancake, "I can't tell you what a relief that is." He knows better and has for 23 years, since friend and fellow "sneaker" Ben Kingsley got busted for routing corporate funds to activist causes. His crack team of overqualified ringers — ex-CIA organizer Sidney Poitier, electronics whiz Dan Aykroyd, blind phreaker David Strathairn, hacker wunderkind River Phoenix, and reluctant actress Mary McDonnell — knows better, too. They're all refugees of the surveillance game one way or another, and they all have their own disillusioned sense of humor on the subject.

Phil Alden Robinson's "Sneakers" is "Mission: Impossible" on a RadioShack budget. It's a heist in spy's clothing, but the most impressive tricks on display don't take batteries. Anagrams are bested by Scrabble tiles, locked doors by well-planted feet, and, once in a while, a good day's work deserves a little dance party. Espionage doesn't get much more effervescent than this, even as it handles a surprisingly nuanced take on modern spycraft. "No more secrets," both a threat and a philosophy in the film, can be weaponized in any direction.

Alphaville

Oblivion is a smoker's rasp complaining that art is overrated. In so many words and more totalitarian style, this is the gospel of Alpha 60, the computerized dictator of the Alphaville colony. Dogma transmits everywhere and whenever necessary, flattening the populace into ice-cold homogeny free of subversive pleasures like conscience or compassion. Into the gray, gotham squalor goes secret agent Eddie Constantine, posing as a Communist journalist and determined to unplug the mysterious voice in every citizen's ear.

It's easy to write off "Alphaville" as noir, no cloak or dagger required. Constantine, face like a papier-mâché bullfrog, is a hero 30 years and a genre late to the call of duty. His gadgets are no more complex than a camera, a pistol leftover from World War II, and a bottomless supply of cigarettes. The city around him, actually the bleeding edge of Paris, antiquates him even further, a trench-coated creature of impulse shrinking from the fluorescent-poisoned view. But his tireless crusade against the voice in the box provides an impressionistic template for the government snoops ahead, as well as a stylish bridge from the private eyes of old.

"Your kind will soon be extinct," promises the mad man behind the machine, Howard Vernon. "You'll become something worse than dead — you'll be a legend." The peerless Jean-Luc Godard mints one in real-time with a spy named 003.

Shanghai Express

Though there is at least one bold-faced liar on the manifest of "Shanghai Express," what makes it among the greatest spy films is its suspicious fugue. In this fog, under these chiaroscuro lights, between these monolithic close-ups, everyone's a double agent. "Don't you find respectable people terribly ... dull?" wonders star Marlene Dietrich, threatening to combust the celluloid with each syllable.

Calling the atmosphere in Josef von Sternberg's doomed voyage a dream is too merciful. Calling it a nightmare, too easy. "You're in China now, sir," says Warner Oland, playing half-Chinese with more grace than his most famous role would suggest, "where time and life have no value." Like most of the small talk in "Shanghai," his diagnosis is more than a little loaded, but he's not wrong about the liminal danger onboard.

Dietrich is infamous, for 1931, the hard way. "It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily," she says. British soldier Clive Brook, the one who got away, has spent five years dreaming of their reunion. Their love story crackles just fine, but Dietrich's better scene partner is in another compartment. As a fellow "coaster" on the rails, former silent film star Anna May Wong is the only other passenger who understands Lily's five-year disappearance. She and Dietrich are given surprising room for their wants and revenges and, most daringly, their chemistry. All's fair on the "Shanghai Express," be it love, lust, deceit, or betrayal. It all looks the same in the sensual, sensational haze.

True Lies

As reported by Yahoo News, Arnold Schwarzenegger showed the French spy comedy "La Totale!" to long-time collaborator James Cameron because of the tantalizing question it posed for an action hero in middle age: "What if James Bond had to go home to his wife and family?" But while that franchise was aiming at opportunists-without-a-country as its new post-Cold War villains, Cameron and company painted a big, sloppy target on the Middle East with their send-up.

Such is the agony and ecstasy of "True Lies," then the most expensive blockbuster ever made and now a time capsule of the genre's ugliest tendencies. While "The Living Daylights" veteran Art Malik finds some grace notes as the big bad, the Crimson Jihad is a reckless substitute for the previous decade's ubiquitous Russians. Jamie Lee Curtis, certifiably game as the Mrs. Bond who eventually earns her double-0, gets put through a sadistic, sitcom-esque ringer because Arnold thinks she's cheating on him. Your mileage may vary violently on whether or not the film winks hard enough to withstand such scrutiny.

And yet, it's James Cameron beating James Bond at his own game. The consummate gearhead throws every last gadget at the screen, concocting sequence after sequence that, for all the homages since, have yet to be topped in spectacle or suspense. The bathroom slugfest. The handheld transfer from falling limo to pursuing helicopter. The horse-versus-motorcycle chase to the roof of a D.C. Marriott. At times, the Cameron-Schwarzenegger union reaches its pyrotechnic nirvana, with director and star each pushing the other to their impossible limit. Take it or leave it, "True Lies" remains one of the most incredible spy films ever made in the purest sense of the word.

Argo

"Argo" could conceivably be one of the best heist movies ever made, with its overall structure ostensibly making it less a spy movie and more of a caper. But the film tells the story of an actual CIA operation to extract six Americans from the Canadian Ambassador's house in Tehran during the 1980 Iranian-U.S. hostage crisis. "Argo" might not hew too close to the facts in certain areas, but its spy bonafides are undeniable.

There's enough slow-building tension in "Argo" to make it as gripping as any of your favorite spy thrillers, but it's also helped by the fact that it's essentially a sort of historical caper. CIA operative Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck) is put in charge of setting up a fake Hollywood movie shoot in Iran as a cover for smuggling the captive Embassy staffers out of the country. It sounds like the plot of some ill-conceived comedy, but is actually based on the real Mendez's 1999 memoir, "The Master of Disguise," and the 2007 Wired article, "The Great Escape: How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran." The result is a spy movie that's relentlessly entertaining, gripping, and willing to mine the absurdity of the situation for dark comedy.

Ben Affleck, who also directs, proved he was more than capable of overseeing movies that took him outside of his native Boston and that were much larger in scope than his previous efforts. As well as delivering a masterclass in plotting, tension building, and action, Affleck also established an impressively immersive tone, evoking the late 1970s and early '80s with an ease that makes you feel as though you're watching the real operation unfold. With stellar turns from Alan Arkin and John Goodman, "Argo" is more than worthy of its three Oscar wins, as well as its standing as one of the great spy movies. (Joe Roberts)

The Third Man

"In Switzerland, they had brotherly love," bemuses alleged corpse Orson Welles in a famous monologue that's half laundry list and half riddle. "They had five hundred years of democracy and peace, and what did they produce?" His answer — the cuckoo clock — is justification for his own evil and a mockery of American friend Joseph Cotten's naivete. The silly novelist, coziest behind a typewriter while holding his next western paperback, is out of his genre and out of his depth in the living ruin of Vienna.

Author Graham Greene's original novella ends like one of those hypothetical oaters, neat and romantic, but director Carol Reed wanted the shadows to win. For most of the film, that's all Welles is, a shadow inspired by real-life double agent Kim Philby. All Cotten and grieving girlfriend Alida Valli have to tilt after is a flick of the dark or the hard, harsh light that cinematographer Robert Krasker keeps just out-of-frame.

And around every black corner, down every condemned alley, and through every dungeon-esque sewer pipe, composer Anton Karas mocks their quest with one of cinema's finest scores, performed exclusively on a zither. The famed "Harry Lime Theme" sounds fit for a juggling act that keeps adding pins and is always swirling faster. It's a carny warning that Cotten's lily white hero never heeds — if you're going to get swept up in the spectacle, at least keep one hand on your wallet.

Notorious

As much as any Hitchcock film, "Notorious" is defined by a single shot, and that shot is defined by deception. It starts with a wide pan, par for the contemporary course, over a grand staircase surveilled from above its requisite chandelier. Just when the frame seems to settle into an establishing shot, boxing in all the partygoers below, it starts to push. The camera weeds out the wallflowers, the passing tuxedos and gowns, and all other bodies but two, until all that's left is Ingrid Bergman's hand hiding a fateful key. The deceit was baked into the celluloid — no one behind the camera could see exactly what they were capturing.

"Everybody is having a good time," explained Hitchcock in a 1963 interview with Peter Bogdanovich, defining both the exhilaration of espionage and his own iconic style, "but they don't realize there is a big drama going on here." There are many worthy spy thrillers in his career on either side of this 1946 release, but as an artist, there is only before "Notorious" and after. The laser-guided camera. The evocatively pointless MacGuffin, in this case an atomic secret bottled as wine. The psychosexual tension between incandescent stars Bergman, Cary Grant, and Claude Rains, sympathetic souls torn between duty, love, and baser sensations.

And if that staircase shot announced the arrival of Hitchcock, aesthete, then the three-minute, Code-flaunting kiss between Grant and Bergman introduced an artist to match the craftsman: Alfred Hitchcock, provocateur. There's no sexier moment in spydom.

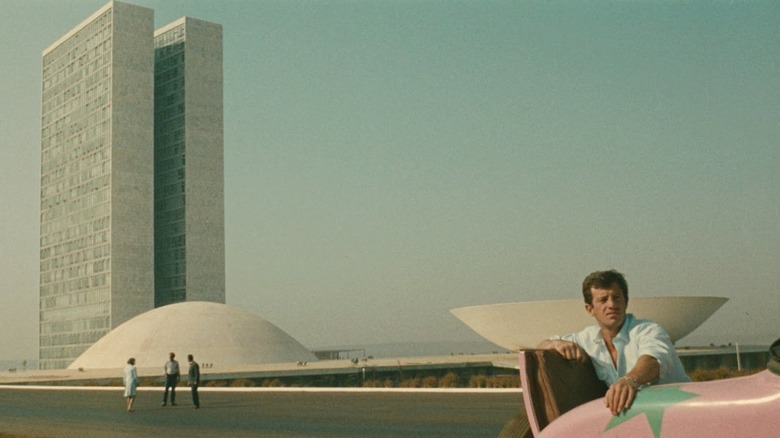

That Man From Rio

When kidnapped amnesiac Francoise Dorleac arrives at a Brazilian beach, the first thing she does is passionately suck face with soldier-on-leave Jean-Paul Belmondo. She doesn't know that he's already risked life and several limbs to save her, his fiancée. When he asks her, not unflattered, if she knows who he is, she replies, "No, but it doesn't matter," and gets back to the kissing.

That's a clue to the audience, shanghaied on the same globe-trotting adventure and only half-aware of the intrigues fueling it, to kick back and enjoy the titillation. Belmondo, after all, is risking that same life and those same limbs for the rest of us. Marvel when he chases the kidnappers on a motorcycle mid-smoke. Thrill at his toreador routine with three oncoming cars. Squirm as he attempts to climb hand-over-hand from one skyscraper to another with little more than a wire and a prayer. Though not the most traditional spy movie on this list — Spielberg cites its high-flying setpieces as a principal influence on Indiana Jones — "That Man from Rio" is Belmondo's Bond, give or take a few extra smirks. He tangles with the villainous Adolfo Celi a year before "Thunderball," and beats "Moonraker" to Rio by nearly two decades. And, at the end of the day, there's only one dinner-jacketed smoothie who could pull off a pink convertible covered in green stars.

Munich

One of Steven Spielberg's greatest gifts has always been transmutation. Signaling the shark with a dragged-away dock. Making the unimaginable might of the T-rex as tactile as a glass of water. In "Munich," along with co-writers Tony Kushner and Eric Roth, he transmutes the complete human cost of espionage to the ring of a rotary phone.

Three off-book assassins for the Israeli government wait in a car outside a Parisian apartment building. Another agent, fixer Ciarán Hinds, calls a specific unit across the street, which belongs to one of the Palestinian terrorists responsible for the 1972 Olympic bombing. When the target picks up, the men in the car, deaf and blind to both call and caller, will trigger a bomb in the phone. Instead, the target's daughter answers. The ensuing panic plays out in near-silence, scored only by the mundane clicks of the detonator being armed. Hinds and team leader Eric Bana reach the car in time to save the girl. Then they call back and kill her father.

"Munich" remains Spielberg's most contentious film by design. His 2005 double-header — this and "War of the Worlds" — bleakly rhymes with his record-breaking 1993 duo, "Schindler's List" and "Jurassic Park." The difference is an artist who has accepted that you can't go home again. As soon as that detonator is armed, he wonders if there's any home left.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door

"Somehow I forgot Freeman even existed," says a CIA overseer late in the intentionally doomed training program to mint the organization's first Black agent. "He has a way of fading into the background." As Freeman, the only candidate to pass, Lawrence Cook is warm milk. He never speaks above a polite hush. At work, he disappears behind Clark Kent-esque frames. When he quits mere weeks after accepting his inert post as Reproduction Section Chief, his bosses couldn't be happier. He was recruited as a stunt and hired as a fluke. Good, clean riddance. They have no reason to believe this invisible man might, say, use what they taught him to organize an underground network of Black freedom fighters.

Author Sam Greenlee pulled his 1969 novel from his own experiences as an intelligence officer for the U.S. Information Agency. It took him and director Ivan Dixon four years and $850,000 in grassroot donations to make it play in Peoria. For all their troubles, it lasted about three weeks. According to Greenlee, the FBI stamped it out theater-by-theater and passed his novel to new recruits by the time it hired its first Black agents.

Any doubts of its veracity will be allayed by the end credits — there's subversion, and then there's "The Spook Who Sat by the Door," a throat-hoarse rallying cry for bloody revolution. For a genre built on and around headlines, no other spy film comes close to its agitprop power. Just five years after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., a moment in time immortalized in black-and-white, "The Spook Who Sat by the Door" arrived in full, ferocious color and survives that way, no less dangerous than the day it was barely released.

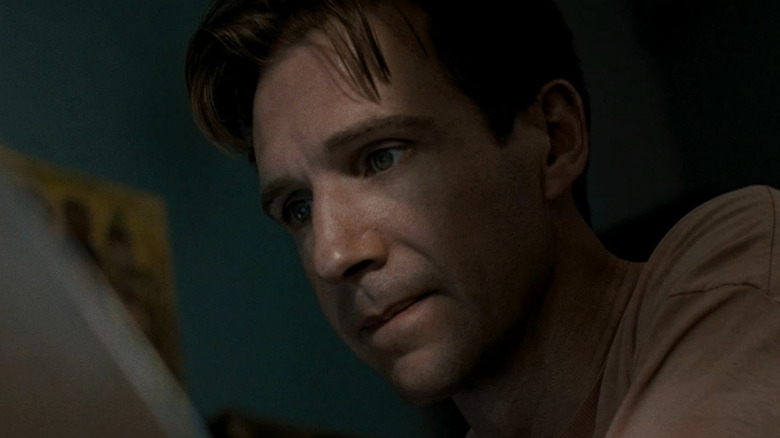

The Constant Gardener

There's something about bringing in an international director to shepherd a British spy thriller that just seems to produce magic. New Zealander Martin Campbell proved as much with "Goldeneye" and "Casino Royale," Swedish filmmaker Tomas Alfredson did the same with the impressively realistic "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy," and Brazilian Fernando Meirelles repeated the trick with 2005's "The Constant Gardener." It may seem prudent to hire a British filmmaker for a John le Carré adaptation, but Meirelles showed that an outsider's perspective on the books of this quintessentially English legend was exactly what was needed.

"The Constant Gardener," based on le Carré's 2001 book of the same name, sees Meirelles unafraid to stray from the source text when needed, focusing on the relationship between Ralph Fiennes' British diplomat Justin Quayle and his wife Tessa (Rachel Weisz) as the real anchor of the film. The result is a love story masquerading as a spy thriller, but one which does a heck of a job at both.

While not technically a spy movie in the traditional sense, there are plenty of clandestine activities, intrigue, and corruption involved to keep fans of the genre invested. Fiennes is brilliant as a British diplomat to Africa, with a gentle yet quietly intense determination to solve his wife's murder. His performance is effortlessly matched by Weisz, who won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her portrayal of Tessa. The performances, along with Meirelles' willingness to expand upon le Carré's novel and his confident direction, make "The Constant Gardener" every bit as immersively cinematic as it is affectingly heartfelt. (Joe Roberts)

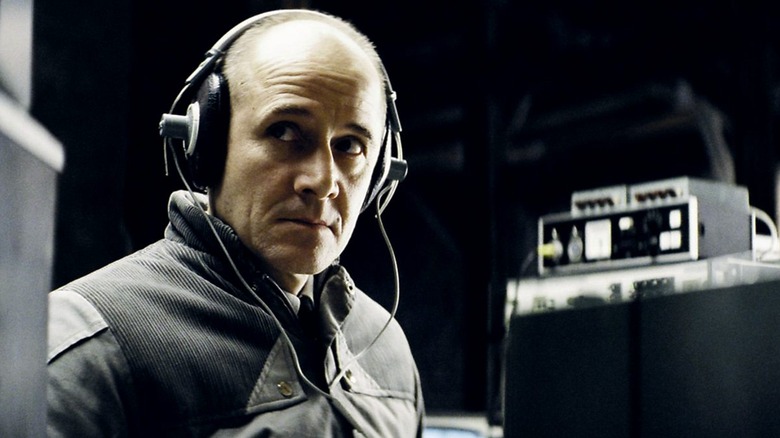

The Lives of Others

In most dramas about the cloak-and-dagger business, morality is treated as a lost cause. Flags matter more than feelings, even though operators spend most of their careers squinting at the other guys. "The Lives of Others" starts beneath a dark flag — the German secret police circa 1984 — and grinds toward the light.

Captain Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Mühle) didn't write the book on interrogation, but he does teach the class. Human nature is a series of ones and zeroes to him, tells and truths. When he receives an unusual target for surveillance — renowned playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) — Wiesler embraces it like any other operation. Bug the apartment. Await incrimination. But all it takes is one whisper of selfish motive from the powers that be to make the eye in the sky question his entire career.

In his feature debut, director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck wrings more suspense out of two rooms than most filmmakers can from the world stage, and wonders if the only difference between peeping toms and guardian angels is who's minding the listening devices.