The Rip Director Joe Carnahan On The State Of The Mid-Budget Action Film: 'If Everything's About Shareholders, You're Dead' [Exclusive]

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

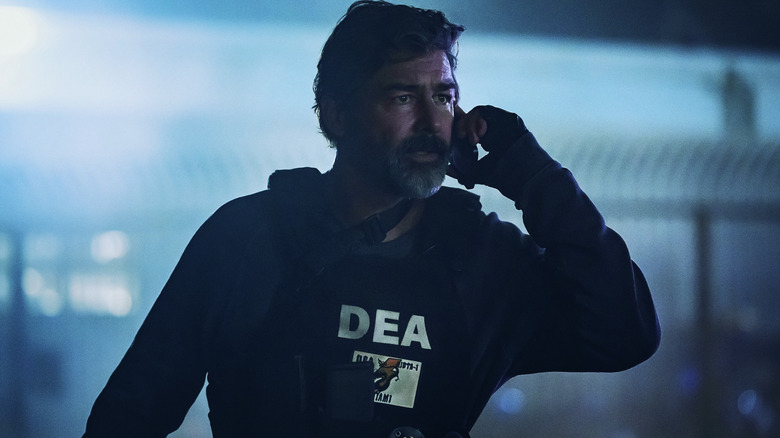

I was hyped when I saw the trailer for Joe Carnahan's "The Rip," an inspired-by-true-events cop thriller that reunites Oscar winners and lifelong best friends Ben Affleck and Matt Damon on screen and features Damon saying the line, "You think I wanna jack this rip?" /Film's Chris Evangelista didn't have a ton of kind things to say about the movie in his review, and while I agree that it doesn't quite live up to the excitement of that trailer, I liked it more than he did and thought there were some fun moments to be found in it.

In any case, I had plenty of questions for co-writer and director Joe Carnahan, the filmmaker behind movies like "Narc," "Smokin' Aces," "The Grey," "Stretch," and "Copshop." Carnahan, a gregarious guy whose palpable enthusiasm almost made me like the movie more in retrospect, was generous enough to sit down with me for 30 minutes over Zoom to talk about the state of the mid-budget action film, which details in this story are based on the real events, this movie's cinematic influences, his working dynamic with Affleck and Damon, some of the film projects he never got off the ground, and much more.

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

The late Tony Scott was a subtle influence on The Rip

Ben Pearson: I want to ask you something very specific right at the top here. There's a scene where Ben Affleck and Matt Damon's characters are speaking with a cartel leader on the phone, and we see subtitles pop up on screen when the cartel head is speaking. But they pop up in this interesting way that I can't recall seeing before, almost like each letter is being spun through a translator before it appears on-screen. It's a pretty subtle thing, but I thought it was really cool. Can you tell me about that?

Joe Carnahan: That's great, brother. Yeah, we thought it'd be kind of interesting to just ... because basically you're saying the two characters, Ben and Matt's characters, both speak Spanish, but I just thought it was kind of a cool little — our effects guys did a really nice little job there of ... I love the way Tony Scott would do subtitles, like "Man on Fire," I always thought that was so cool. I think we just kind of throw it away sometimes, and I didn't want to do that.

How would you characterize the overall experience of making "The Rip" compared to the rest of the movies that you've directed?

I've gotta say, Ben, I've never had a better time on set, or felt more supported. And when I say better times, it's like, listen, we try to have fun on every set and try to remind ourselves that we're lucky to be doing this, and let's just enjoy the process and so on. But this was just, to have their support, dude, and have Artists Equity behind you and Netflix behind you and everybody putting their best foot forward, it's the dream, man. It doesn't happen often enough. So it was great.

The unique deal for The Rip resulted in a 'true communal experience'

You mentioned Artists Equity, and I saw the news story a little while ago that there's a slightly different deal being done with this movie compared to some other stuff. Were you a part of those discussions?

We knew about it early on. It was never kind of a headline thing I think they put out there. We knew about it. I knew that the boys are pushing on that, and I think it's such a smart [thing]. And to be at the vanguard of that, it makes sense for it to be Matt and Ben, because I think that they've been doing this a long time, at a very high level. And the idea of incentivizing a crew so that everybody — caterer, gaffer, hair and makeup, the transpo guys [gets a bonus if the film hits certain viewership thresholds] — that's huge. Then it becomes a true communal experience. We're all kind of in this together, and it's not this separation of the movie star, and then everybody else. Or the director, and everybody else. I really think that's tremendous. And I think it's also wonderful that Netflix is like, "Yeah, we get it, man. We understand where the business is going, and let's see what happens here, and let's see if it bears fruit."

Could you feel a difference on the set compared to some other projects that you've worked on?

You know what you feel, brother? You just know that you're in good hands. And I think a lot of times, I've had to do five jobs, and in this one, I just had to do one. That was the biggest thing. And then what you get in those instances, it's Juanmi Azpiroz, my DP, and Kevin Hale, my editor, these guys I've worked with on many, many films, it allows us to do our best work because we're not multitasking because we have to make up for, "Okay, well, these guys don't know what the hell they're doing." And that happens sometimes. I've only made four movies, really, inside the studio system — I think five, including this one — and they're rough.

When you're out there in the world trying to put these indie movies together, it's tricky, dude. And I don't want to do them like that anymore. Walking around that afterparty last night, I was like, "Oh, I could do a lot more of this. This is great."

Joe Carnahan wanted to get ahead of the Reddit nitpickers

Warning: Spoilers ahead for "The Rip."

I'd like to talk about a spoiler-y moment, but we're going to hold this until the movie comes out, so feel free to speak openly. At the end of the movie, we find out that Damon and Affleck's characters have been working together to find the rat in their group, and Damon gets to give this ... it's kind of this movie's version of a "how do you like dem apples" speech, which is so satisfying as an audience member. So I was hoping you could talk me through getting to that moment, making it feel earned from a story perspective, and then actually working with Damon to get what you wanted out of him, performance-wise.

It's kind of a trite thing to say, but it really all begins with the script. And I don't have an affinity for this type of writing, so I'm always amazed — I watch Rian Johnson, I'm going, "This guy, this is f***ing fantastic. This is a magic trick." So we spent a lot of time, myself and [co-writer] Mike McGrale, drilling down on what the specifics of that would be, and really spent a lot of time in the outline phase. So when you get there — because you're building a watch. This thing has to keep time, and it has to hit at seconds and hit at particular moments. So, in that, it was so great because Matt now embodies the "here it comes." And it really begins with these guys are just staring each other down and the guns come out.

I also don't want to wind up in some Reddit thread where some guy goes, "Well, why didn't you just kill him when they got into the car? They should have killed him right away." They have their weapons out. They know what's going on. So, now it's going to be very difficult. "Okay, what do we do? They're the bad guys, how do we make a move on these guys?" So, that was number one. And then, you think these guns are designed for this kind of stand-off for the two of them, and it's not until there's a very deliberate camera move, where Ben leans forward, and now it's like, wait a minute, it reframes, and now [Steven Yeun's character] Ro is the subject of the scrutiny.

So that when [Damon] says, "Unless you're lying like me, which then it's a f***ing art form, and I've been lying to you all night." I love that moment. You could feel in the audience last night [at the premiere] this palpable glee, like, "Wait a minute, wait a minute," you know what I mean? It's like, "Jason Bourne's not a bad guy! Batman's not a bad guy!" So it was deeply satisfying, brother. You want to give an audience those great moments, those wins. I love that. I do, I really do.

As soon as I finished watching the movie, I immediately went to search about the real story that this was based on, and didn't really find that many details. I just saw some arrests were made, there was money in the house, and that was kind of it. Did you guys have more access with the research that you were able to do into some more of the specifics of what actually happened here? Or did you just kind of take that basic framework of the news story and say, "This is a cool idea. Let's completely invent a bunch of stuff to happen here"?

[Technical advisor] Chris Casiano was actually involved in that rip. So he was able to fill in and give us a lot more color in terms of those details. A little one is like, in the actual rip, which took 42 hours to count — which, obviously we're not going to do a 20-part series on this thing and watch them count for 42 hours — but when they got to the, there's an actual DEA-held Wells Fargo, it's a real place, and there was a guy with a clipboard waiting for them, and six armed men, and they excused the other two officers, put them in Ubers? That's all true. And then they used a two-story counter, this giant electronic counter. So, that moment where the readout is $20 million, and the card [says the same number]? That actually happened. So, there's stuff in there that we stayed true to the authenticity of it.

And then as you mentioned, it's like, then you got to invent the rest of it, man. You've got to invent all the little pinwheels, and the Rube Goldberg contraption that eventually drops a net over the mouse. But we did have a little more insight into that than somebody who's just reading about it.

Utilizing the inherent power of a Ben Affleck/Matt Damon team-up

Tell me about working with Ben and Matt as performers. Obviously, you've worked with Affleck before [on "Smokin' Aces"], but what was it like just teaming up with these guys and really collaborating with them? They're such forces in the film world.

Yeah. The movie really trades on these two very, very distinct things, which is you've got two guys that have been friends since they were kids, which is one thing. And then you've got two guys that also became movie stars, which is like the double unicorn. You know what I mean? When does that happen? How does that happen? So, at times, they're interwoven. You see Matt and Ben as Matt and Ben, when they're upstairs and they've just discovered the money in the wall, and Ben's like, "Dude, it's me. It's just you and me." That's Matt and Ben. You know what I mean?

So you're getting this great gravitational sense of their hold on an audience, of 30+ years of being in this business and seeing their faces on screen and knowing their history, and the two of them winning an Oscar when they were kids. There's a lot of goodwill and a very endearing quality to that. Then you also happen to have two real world-class filmmakers. Guys who just know the inner workings and how the machines function, and give you the grace and the support and the room you need to be great, to really do your job at a very high level.

I was going to ask if they felt deferential to you, or if they came up to you and were like, "hey, maybe we should do things this way." What was the vibe like between you guys?

Discussions were like, "Dude, do you think we need this line? I don't know if we need this line." And invariably, they were always great suggestions. They never intruded on the process. Matt made a joke to me one day: I said, "Dude, do you mind doing this" And he was like, "Hey Carnahan, I'll pull faces for you all day, pal. I'm here for you. I'm the boss, I'm the studio, but I'll pull faces on whatever you need me to do." And he was being funny, but Matt's the guy that hangs around and does his own hand inserts. You're shooting his hand. I said, "Well, dude, go home." He's like, "No, man, this is what they pay me for." There's a consummate professionalism to both of those guys that is so inspiring and sends the right kind of ripples out across that lake, that's like, "Oh, okay, we're all doing this for the right reasons with the right people."

The Rip filmmakers put the movie through its paces

If I have the timeline right, you guys wrote the script and then you cast Ben and Matt. Was that correct, or did you have them in mind when you were writing?

By the way, two years ago, this script did not exist. It didn't exist until May of 2024. And Dani Bernfeld, who was at Artists Equity, who's really the wonderful ignition on this thing, I had been in there, I talked to Ben about some stuff, we talked about all of us figuring out something to work on and so on. And when that was done, Dani's like, "Listen, just give me 48 hours. Before it goes out in a larger context, give me 48 hours with this movie. Let me figure it out." And 24 hours later I had Matt, and 24 hours after that, I had Ben.

It was funny because they're producing it, obviously, and they're going, "Let's talk about cast. Who do you see in the movie?" I go, "Well, you guys would be okay!" [laughs] "I don't know. What do you think? Maybe you guys is perfect casting." And then honestly, we were just off to the races, man. It happened very quickly. We were done shooting that movie by the end of 2024, and spent last year editing and fine-tuning it and doing all that good stuff.

Did you have time to rewrite anything to their strengths, or was that all found on the day where you created a little moments for them?

We had one little day of reshoots to clarify some stuff, because I think we really were trying to hone this thing, so it would cut through anything. The story moves. And I think all the extraneous stuff that maybe we would find cumbersome after a while, we just shore away slowly. So that's what that process was. But there was a lot of discussion about the very end and what that would look like, and that was a very different thing that went through a lot of iterations. We finally got a version that we all love.

That's the thing about the movie, it's the version I love, it's the version they love, it's the version Netflix loves. It's not like we settled for everybody's second-favorite choice, which sometimes happens in instances like these. You go, "Okay, well, this is the one we can agree on, so we'll let this..." You don't want that. You really want to feel like you put your best foot forward.

Right. Yeah, I was going to ask about different iterations of the story, and whether or not that iterative process happened early or late. Was that in the edit or was that in the writing, pre-production stuff?

I always say there's three films: There's the one you write, the one you shoot, and the one you cut, and they can be wildly divergent in what they wind up being. There's an application we use, FrameIO, which is basically, you watch [the movie], but you can make comments on specific moments and go, "We need to do this here." I think I was somewhere in the 13,000 range of individual comments on the various cuts over the 10 months or whatever, because we just wanted to make this thing a rocket sled. And my girlfriend jokes about it: I'd get up at 3:00 in the morning, and [be like], "Here we go." And we did it again and again and again.

Kevin Hale, my buddy who I've known for 30 years who cut the film, early on, I realized I was being so abrasive, because he took one note that I had just written, "Flat, flat, flat. There is no narrative push here, there is no drive, this sucks," and he says to his wife, "I don't think Joe's happy with this cut of the scene." But brother, when I tell you we roughed this thing up, we really took this thing through its paces. We really knew what this movie was at the end of the day.

Joe Carnahan knows you can't make movies to please shareholders

You tend to make these really muscular, action-focused movies, what is it about that type of film that keeps you coming back?

It's funny, because I think I probably have a very different career if I just made "Narc" or "The Grey." I think my ex-wife said to me, "I don't like your comedies," which is probably why she's my ex-wife. But I have an affinity for these things because I think that I love the ... I think this movie is made and built from very intimate, very human moments. Whether it's the guys, it's Matt and Ben talking about time and how much time has passed and what they're going to do with what they have left, or Catalina talking about just this little bit of money could change [her] life. I like stuff like that, man. And I think the humanistic parts of it are the most important to me.

Because once you get an audience invested and they care about the characters they're seeing on screen and these people seem relatable, then you can really f*** with them. Then you can put in all the contortions and all the twists and turns, and all that stuff that you want from a dramatic standpoint. And then when violence does happen, and this paroxysm of stuff takes place, it's truly shocking because now you care. Like Catalina laying there saying, "Where's the dog? How's the dog? Is the dog hurt?" That's her character. She's got a bullet in her leg, and she's worried about where the dog is. And then conversely, the audience goes, "Oh my God, did they kill the dog? They killed the dog?" It's another layer of dread that you can hang on them.

So, yeah, man, you want to feel like these types of movies are coming back into vogue. I have nothing against superhero films, I have nothing against giant monsters, I have nothing against ... I love a lot of those. Those Marvel movies are fantastic. James Gray said something really brilliant recently, like, "We've mainstreamed this one type of tentpole blockbuster film, so you lose stuff like this." So some people say, "Don't you wish this is in theaters?" No, because Netflix does allow for you to do these things. It does allow for these things to be a little different and varied.

Yeah, I was going to ask about that. It feels to me like with a few exceptions — and I think your work and especially "The Rip" qualify as those exceptions — it really does feel like Hollywood has lost the art of the mid-budget action movie, and I was wondering if you had any theories about that.

Brother, I think it's like, listen, because when you replace people that are genuinely film lovers and people who understand the business, and love to go to movies, who love to make movies or love to experience movies, and you're replacing with bean counters and bureaucrats and people that could care less because it's bottom line-based, then you're going to get this, it's like, "Well, we have to talk to our shareholders." If everything's about shareholders, you're dead. You're just dead. You're going to invariably make a version of the same movie every time, and I don't have time for it. I don't have time — earlier, we were talking about time and the importance of time. I don't want to waste two hours with something that, I just saw this. I just saw the same thing.

That, to me, is the great predicament that we're in, but I think movies like this, and I think we had a good year of films, solve that. Because the audience votes with their feet, man. They vote with their feet. Do they show up? Asses in seats, that's how they vote, or a number of streams, that's how they vote. So, I think that you're seeing the worm begin to turn here.

The Rip director Joe Carnahan reveals the movie that got away

You mentioned the indie approach earlier, and from the outside, it feels like it's a purposeful strategy on your part to make movies that never really seem to get bogged down with gigantic budgets. So, that's my perspective from a viewer. Does it feel that way to you?

Yeah. Yeah. It's why [actor and frequent collaborator] Frank [Grillo] and I started [production company] War Party. We wanted to be able to just go and do. I don't want to spend two and a half years, three years on one movie. And also, I like shooting shorter schedules. Give me what I need to make the movie, and then let us go make the movie. And listen, I'll put the action up in this film with anything that's been done recently. I think it's fantastic. But I do believe, again, it's like, "Well, it's got to be a big swing. If it's not a big swing, it's got to be a microbudget, [or] a $5 million horror film."

Again, those are the way that they've worked the economics of this business, and I think it's faulty and I think it has to change. But yeah, I don't want to be bogged down in that, dude. I don't want to have to deal with this slog of bureaucracy, and "Well, this junior executive thinks..." It's like, "Oh, come on, man." We've got to get away from that stuff. You've got to let filmmakers go make films.

Definitely. So, you've been close to directing many projects over the years, you've talked a lot about "Mission: Impossible III," but there was "Uncharted," "Five Against a Bullet," "Motorcade," "Undying Love," the list goes on. You don't really strike me as the type of guy who sits around wondering what could have been, because you stay pretty busy. But if you had to pick a project, is there anything that feels like "the one that got away" for you?

I wish I could have made "Killing Pablo" because I spent a lot of time on that book, and I really loved it and I thought I wrote a really good script. And at the same time, José Padilha and Wagner Moura come along and do "Narcos," and it's like, "Well, that's dynamite. I can't even..." You know what I mean? It's like, what do I do? You can't complain, because they made something fantastic. But that was one I wish I could have, god, I wish we could have just gotten in there and done that at the time.

And I think my "Death Wish" script, which was, even though I got credit for the Bruce Willis version, my script was nothing like that. And it remains probably the best thing I think I've written. I would love another shot at that one, because that was a really, really specific movie that I wanted to make.

Do you think that's possible? With a few more years of distance?

Yeah, the thing is, I don't even know that you need to call mine ... It was so kind of in and of itself. I just called the [protagonist] Paul Kersey, but beyond that, [there wasn't a connection to the franchise]. It was wildly different, it took place in L.A., it was just a very different approach. I'd like another at bat with that one.

Joe Carnahan says a Nemesis movie would 'play huge right now'

Do you think there's a chance that "Nemesis" ever sees the light of day?

Oh, god. Well, listen, when your plot is, they're going to kill the President, and someone goes like, "That movie could be over in 30 seconds." It's like, "Yay!" I think it's like, no, I think that ... I thought my brother and I wrote this really cool version. Because I thought Mark [Millar]'s graphic novel was great, but very thin. Like, "Okay, what if Bruce Wayne was the Joker?" basically, is kind of the [premise]. But I did think we did a really cool thing in there, and I think the idea of going in and starting to execute politicians is probably, would play huge right now. But again, yeah, that's another one that I think would be a lot of fun. How do you do that?

Yeah. So, I was wondering about this: If you're with a handful of directors swapping stories about wild moments on set, what's the story that you break out? Do you have a favorite that you break out from your career?

Those I couldn't tell in mixed company because they're too specific. I'll talk about this one, about "The Rip" that I just love because I think it was — the shot didn't wind up in the movie, but I thought it was really great. For the end of the film, I had all of Matt's kids and all of Ben's kids, and their mothers, and their loved ones, and their wives, and so on yell for Jackie [on the beach]. So, when they heard that the first time, they heard it coming from voices they knew. And there was this really great reaction that they had. And Ben said to me later, he goes, "Matt was like, I heard Chris, I heard Ben's mom's voice, and I was like, 'Wait, are we in trouble?'" But it kind of pierced the membrane for a moment, that fourth wall, like, "Who is that? What is that?"

You could see it, and there's a bit of puzzlement, but I think they understood what I was going for. I wanted to see what that would sound like, if you heard your kids yelling that name, and you recognize, there's an immediate familiarity with that. [What that would] look like in your expression, which I thought was so cool. And I wish we could have kept the shot. You see a little bit of it, but not what it was.

Gotcha. So, no film shoot ever goes exactly according to plan. Can you remember a time when things went wrong on this movie or some obstacle came up and you and your team had to figure out a solution?

Not with this one. I could go to "Boss Level," and give you like, we lost 15 days with the schedule, and it's like, "Okay, we ain't doing what we thought we were doing. So now Frank has to just kill everybody with the mini-gun." But it wound up being great. This was — again, Ben, this was such a joy because you've got these guys giving you everything you need, within reason. It wasn't like we were extravagant, like it's money, money, money. No, here's the plan, here's what we're going to do, here's how we're going to execute it, let's go do it. And that's all you want, man, is just that mutual understanding. So, no, I wish there was the hard-scrabble ... I think the truck going over the thing at the end was tricky because we knew we're doing it for real. This isn't CG. We're taking this thing over this overpass, under the thing, and it just went, it just chef's kissed. It was great.

Kurosawa, Michael Mann, and Fritz Lang influenced the look of The Rip

A lot of this movie takes place at night, so it's pretty dark, but even some of the interiors are dark as well, and I was curious if you could tell me about your approach to lighting and the overall look of the movie.

Juanmi and I spent a lot of time talking about light and shadow and color. When you rewatch the movie to see how the sausage was made, green is obviously money. Red is Jackie's color, even down to the little girl at the end on the beach has a red scarf, her red scarf. Blue is the color of cops. So, we're messing with those moments, and even, when Matt is giving the moment, the penultimate thing before the big [conclusion], it's just this flashing of red across him and Ben. This is all about Jackie, man. And at night, that darkness and playing with that darkness, that kind of inky darkness of candlelight, and so on. But the green, as the movie progresses, gets more and more emerald like Oz. It's out there. This is the fantasy that "I could take this money and this isn't real."

So, we really, really spent a lot of time discussing, watching movies, looking at noir films, watching, like, "High and Low," Kurosawa, if you watch it, there's a lot of staging with deep focus and all the characters are in there. And stuff that we knew. Like, "Watch how these characters move inside this frame. It's really impressive." Then you're trying to replicate a sense of that. But it also feels very kind of verite and of the moment. So, it's staged, but doesn't feel staged. I also think it allowed us to be on stage during the day and still have the night shoot, and really control and dial in the light with the kind of specificity that we wanted.

Yeah. Were there any other cinematic influences that you looked at aside from Kurosawa? What were some of those noir movies?

Michael Mann's "Thief." Soderbergh — it's so funny, we looked at "The Limey," and we were like, "Too much." [laughs] What was another one we looked at? I think Fritz Lang's "M," we looked at that, because it's very noir-ish, and very hard shadow, hard key light. This is kind of de rigueur for the way we approach this process. Todd Hido, the photographer, we loved his coffee table books, and love that look. There's a couple of wide shots in there, it's like, "That's a Todd Hido picture." And we spoke to him, we got to talk to him, which was so great because the idea was have him come out and photograph this, and we'll try to replicate what he's doing. But I think he'd be happy with what we did. But yeah, it was mostly that, and then the images, imagery that we'd go, "That's perfect for this."

That's very cool. All right. So, I think I have time for one more question. When you think back on your experience making "The Rip," what are you the most proud of?

Bro, I'm most proud of, I think, that it all came together. That it's better than it was on the page. That the movie wound up being better than the script, I think. And I'm most proud of just how wonderfully heartfelt those performances are, and how much I learned as a filmmaker, and how much better I think we all are as a result of having this experience, and knowing we may have put this one in the center field bleachers. "This is good. We like this." But yeah, man, just being able to still do it, dude, to still be able to work, you can never take it for granted. And for that, I'm extremely happy.

"The Rip" is streaming now on Netflix.