Wicked: For Good Is The Latest Example Of The Biggest Problem In Hollywood No One Talks About

The explanation for why a film flourishes or flops is rarely rooted in a single cause, but studio executives are always looking for a quick scapegoat. After "Lightyear" flopped financially, anonymous sources told IGN that Disney leadership allegedly blamed the inclusion of a same-sex kiss, as opposed to the multitude of factors that contributed to the film's underwhelming performance. Similarly, after gaining viral fame online due to fans dunking on it for likes on social media, "Morbius" was re-released in theaters when those in charge foolishly assumed trending on Twitter would translate to ticket sales. Hollywood is notorious for taking the wrong lessons from its failures and successes (cough, the developing Mattel Cinematic Universe), and there's no greater example of that than the response to women-centric blockbusters.

There has always been a structural imbalance across binary gender lines (and even more so for those outside of the binary) that produces systemic disadvantages for women-led or women-directed projects. It's a double standard that unfairly allows men to "fail upward" in their quest to become an auteur while women are punished if they don't exceed expectations. With this precedent in place, it also means that impartial general discourse and critical assessment of films about, made by, or marketed towards women are nearly impossible. When misogyny and blatant partisanship are baked into every aspect of our existence, how do we know when a critique is being made in good faith and not the result of a person's implicit bias or overt hatred for women? When a film is being praised, how do we know it's coming from a place of sincerity and not defensiveness, given what the film is already up against (like trolls "review bombing" on Rotten Tomatoes)?

"Wicked: For Good" is just the latest film at the center of this conundrum.

How do we dislike movies that are never just movies?

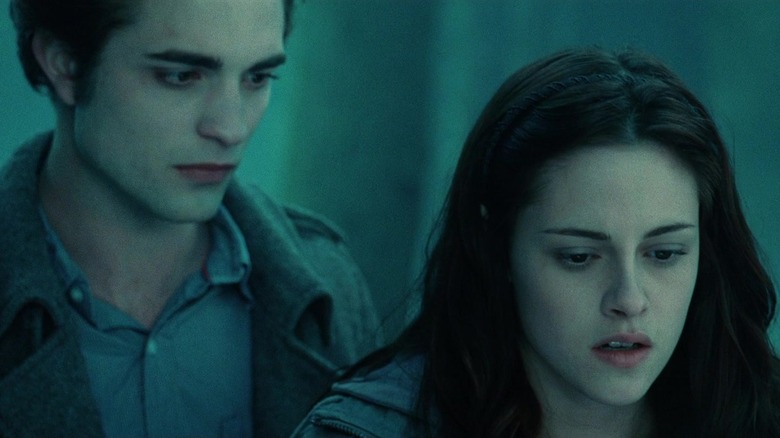

All movies can be enjoyed by audiences regardless of gender identity, and while the same is true of films like "Twilight," "Barbie," and both "Wicked" movies, let's not pretend society is as accepting of men who appreciate these kinds of stories. And in a cinematic landscape dominated by acceptable multiverses folding in decades of lore, crossover material, and canon debates, it's important to remember that the movies like the above-mentioned also have existing fanbases primed to love them.

In my review of "Wicked: For Good," I acknowledged that the movie itself is fine, but the deep affection I have for the music, story, and characters renders my "film critic" assessment irrelevant. All big-budget tentpole blockbusters that are popular with the mainstream audience are easy to hate, and it's often seen as cool or even morally righteous to "take the studio system down a notch." However, complications arise when you accept the reality that a lot of people use these films as a vehicle to express misogynistic thoughts and behaviors.

Critiques of films that are overtly feminine and not like, say, "The Hunger Games" — where they're dystopian action thrillers that just so happen to feature a woman in the lead role — often feel targeted or particularly venomous, with an undercurrent of a moral failing associated with those who like them. There has been a documentable uptick in hatred against women in recent years, and that hatred is extended to things women enjoy. This isn't to say that anyone who hates "Wicked: For Good" hates women because that would be absurd, but it is to say that it's difficult to even express critical sentiment given how quickly it can be weaponized by those who do.

How do we like movies that are never just movies?

The phrase "not like other girls" depreciates "other girls" and creates a competition for girls to stand out in a gender that others perceive as a shallow mass with no individuality or character. In a society that devalues femininity, this also means that those who love things associated with femininity have been trained to love fiercely and defensively. Countless "In Defense Of..." articles have been written about films loved by women but deemed "bad" by the status quo (see: "Grease 2"), and critics writing in favor of contemporary films under this umbrella know they're fighting an uphill battle before they even begin. It's why a voice like Amelia Emberwing is so refreshing, because in her positive review of Nia DaCosta's "The Marvels," she refused to include preemptive statements to try and offset the predictable fury from superhero fans incensed that women heroes exist in the Marvel Cinematic Universe at all.

I adored Dan Trachtenberg's "Predator: Badlands," but saying as much on social media opened the floodgates for people to respond, "If females like it, know it's just gonna be straight up dogs***." (I'm not linking to these clowns and giving them the clout they want, sorry.) If this is the response to a movie with a predominantly male audience, how are women supposed to express joy for films that society already deems unworthy? There's pressure on us to love louder with more hyperbolic methods of emotional expression, lest we provide an inch of doubt for bad-faith actors to turn into a marathon of intolerance. And this doesn't even factor in intersectionality, where a movie like "Wicked: For Good" is compounded by the fact that Elphaba is played by Cynthia Erivo, meaning the film must also combat attacks rooted in misogynoir.

Why aren't women allowed to have 'bad' movies too?

Let's say the naysayers are correct and a film like "Wicked: For Good" is an insult to cinema and one of the worst movies of the year ... why does it matter? Of course, this isn't to encourage an increase in Hollywood slop or a desire to see more affronts to filmmaking produced on a large scale. The point is that we make plenty of "bad" movies that are extremely popular with male audiences all the time, yet they're not treated as an omen for the crumbling of humanity.

The "Fast & Furious" franchise went to space in "F9" and was rewarded with more sequels, with "Fast X" landing the fifth-most expensive budget in cinema history. All three "Hangover" films are in the top 50 highest-grossing comedies of all time, as are the three current "Meet the Parents" films (with the legacyquel "Focker In-Law" slated for 2026). "But those films aren't bad!" I can already hear you furiously typing in my replies, and like, yeah. Exactly. Taste is subjective, and whether or not a film is "bad" is completely up to interpretation. But when it comes to films about, by, or marketed towards women, the general consensus is that "bad" is the default until proven otherwise. In promoting "Bottoms," Ayo Edebiri wisely told The Los Angeles Times, "It's radical to get to be ourselves, to get to be stupid, to get to choose whether to be exceptional or unexceptional." And she's right.

Not to be all "let people enjoy things" about it, but more specifically, why is enjoying "Wicked: For Good" a character flaw yet enjoying "Deadpool and Wolverine" is "having fun?" Only one of these films is attempting to tell a story about propaganda, government grifters, and social injustice.

There's no winning for any of us

I've been writing as a woman on the internet for over 15 years now, and in that time, I've taken enough psychic damage to anticipate the responses before they arrive. There will inevitably be readers who skim this (sometimes disingenuously, sometimes helplessly) and fail to recognize that I'm not talking about specific women-focused blockbusters but talking about how we talk about women-focused blockbusters. They will miss or refuse to engage with the fact that I am not critiquing the discourse surrounding any single film so much as interrogating the aspects that build to these cultural conversations. And the distinction matters.

Discussions about women-centered blockbusters cannot exist in a vacuum because they are shaped by the compounding of assumptions, pressures, and prejudices — both celebratory and hostile — that stockpile around women-focused cultural production. This is exactly why anyone entering these discussions must be willing to perform an internal audit of their own tacit predispositions. Where do our reflexes come from? What ideological frameworks hold them up? And what is missing by pretending they aren't there?

"Wicked: For Good" is a story that burrows into the uncomfortable question of whether meaningful change is best pursued from within the structures that constrain us or from the margins that resist them, and neither strategy emerges as wholly victorious; both come with compromise, loss, and moral murkiness. And that complexity mirrors the very challenge of talking about how we talk about women-centered media.

Studying women-led blockbusters requires the same expansive richness found somewhere over the rainbow, yet we are constantly pressured by society to drag it toward simplistic, sepia-toned conclusions.