Beau Is Afraid Director Ari Aster Isn't An Auteur, Unless He Is

With the release of Ari Aster's third feature film, "Beau is Afraid" (read our review here), the word around the virtual water cooler is that Aster has solidified his place as the next great auteur. The word "auteur" gets thrown around a lot these days, joining the ranks of words like "iconic" that have seemingly lost all meaning in favor of becoming a way to say, "I really like this." Artistic assessment by the masses has grown increasingly hyperbolic, with every new film earning as many 5-star Letterboxd comments reading "a masterpiece" as it does 0.5-star declarations of "the worst movie ... ever." But auteur theory gained prominence back in the 1940s, birthed from French theorists André Bazin and Alexandre Astruc and given its name by American film critic Andrew Sarris.

The foundation was based on the idea of "director-as-author," but has evolved to also encompass a director's signature style or recognizable motifs. Easily identifiable examples include Sam Raimi's use of traveling shots or the existence of the "Wes Anderson aesthetic." We can debate whether or not those examples truly fit under the definition of the theory until we've run out of words, so for the sake of argument, let's think about "auteur" in the commonly-understood sense of the word.

While I certainly do not doubt Aster's talent (I am ride or die for "Hereditary" in ways that probably have me on a watchlist somewhere), it's hard not to wonder what it is about Ari Aster that allows him to be an "auteur." Because make no mistake, auteurship is not something that is earned based solely on meritocracy. Film is a collaborative medium. If someone is an auteur, it's only because someone along the way has given them permission to do so.

A message from Pauline Kael

I first learned about auteur theory in college but was fortunate enough to have an incredibly rad film professor (shout out to Dr. DiCarmine) who got me hip to the work of Pauline Kael, arguably the most vocal opponent of auteur theory. In "Circles and Squares" her famous 1963 takedown of the theory for Film Quarterly, she loathed the idea of categorizing directors, because it implies that good directors can't make bad movies and bad directors can't make good movies. As time continues to prove, she's right.

Her cynical approach to auteur theory is refreshing, and filled with hilariously sharp-tongued barbs like "How much nonsense dare these men permit themselves?" I don't see eye-to-eye with Kael on all things, but she brings up incredible points about the problem with labeling directors an auteur, like how doing so makes it difficult to assess a director's films in a vacuum, with all of their works intrinsically becoming connected throughout the entire filmography. "There is no rule or theory involved in any of this, just simple discrimination; we judge the man from his films and learn to predict a little about his next films, we don't judge the films from the man," she said. I especially love her use of the word "discrimination," because this, to me, is the core issue with auteur theory — it's inherently discriminatory by nature.

I can't help but wonder how Kael would feel to find out that Quentin Tarantino, one of the most prominent auteurs of our time, is expected to end his filmmaking career with a film allegedly inspired by her. Perhaps this film will be Tarantino's way of working through the label attached to him for the last three decades.

Who gets to be an auteur?

Auteurs are typically seen as one-in-a-million talents, but that's not exactly accurate when the field of directing is implicitly biased. Who is allowed to be an auteur is dictated by factors unrelated to talent, as systemic oppression at every intersection that encompasses a person's identity impacts how the cinematic system at large operates.

Julie Taymor, an undeniable theatrical auteur spoke in an interview with Refinery29 where she talked about the way male directors are given permission to take bold, creative swings regardless of audience response, whereas women directors are punished for doing so. "It's about respect," Taymor told the publication. "There isn't a sense of awe about women [directors]."

"Across the Universe" is a phenomenal example of what she's talking about, as the film boasted almost 5,000 extras, hundreds of dancers, handmade puppets inspired by the Bread and Puppet theatre, stunning and precise displays of choreography, 33 reimagined songs, and required over 70 locations. It was an ambitious undertaking, to say the least, and yet those that disliked the film called it "messy" or "jumbled," completely ignoring the meticulous skill and strong creative vision on display.

Refinery29 brought up Darren Aronofsky's "mother!" in comparison, another film that polarized viewers and was a massive creative swing, yet one that has a capsule judgment on Rotten Tomatoes that reads "There's no denying that 'mother!' is the thought-provoking product of a singularly ambitious artistic vision, though it may be too unwieldy for mainstream tastes."

"On something like 'mother!,' even if people didn't like it, they think they should think there's something important there because he's Darren Aronofsky," Taymor said. "So, you have to consider that there must be something that you missed. It's almost like you're not up to it."

Whataboutism helps no one

Criticizing the very concept of an auteur feels like slaughtering a sacred cow, and people often confuse critiquing an idea as diminishing the accomplishments of those often graced with the distinction. Look, I'm not enough of a contrarian to pretend that I don't get weepy over the sentimentality of Steven Spielberg or mark out whenever another filmmaker tries out an Alfred Hitchcock dolly zoom, but I can love filmmakers and also recognize that Hollywood has an "auteur" problem.

And to an even more annoying extent, pointing out the fact cis, straight, white men are overwhelmingly labeled auteurs due to the way the industry prioritizes their voices often inspires the cyclical cries of whataboutism. "What about Spike Lee?" "What about Guillermo del Toro?" "What about Julia Ducournau?" It's a form of deflection that tries to both trap the person critiquing as well as shut down any further interrogation. Auteurs are already exceptions and not the rule, and pointing out a director from a marginalized identity that has been able to "defy the odds" is not the flex people often think it is.

According to the annual UCLA Hollywood Diversity Report published last month, only 1.7 out of 10 theatrical film directors are people of color, and only 1.5 out of 10 are women. Directors of films that debuted on streaming platforms fared a bit better, but not by much, so the fact that there are women or people of color that are considered auteurs at all is nothing short of a miracle. It also means that I should legally be allowed to throat-chop anyone who evokes the name of Jordan Peele as "proof" that Hollywood doesn't have problems hiring Black directors.

To be the best, you've gotta beat the best

Directing a movie is a job just like any other, and no one person is wholly responsible for a film's success. And yet, as the director serves essentially as the "captain of the film team," they tend to get all of the glory ... or all of the shame if it doesn't go well. Karyn Kusama lamented being put in director jail after "Jennifer's Body" failed to perform, even though it has since been reassessed as a cult masterpiece, and the poor reception has now been identified as an error in marketing. It's hard not to see her identity as a contributing factor when someone like Quentin Tarantino saw lackluster returns with his and Robert Rodriguez's "Grindhouse," but it instead brought him even more opportunities from studios hoping to work with him. Labeling someone an auteur gives them the wiggle room for failure, and puts an unfair pressure for perfection on everyone else.

While "auteur" was never meant to be synonymous with "the best," the phrases are often used interchangeably, which is a joke considering the directorial playing field has never been equitable. As Ric Flair taught me, "To be the man you've gotta beat the man," and if being labeled as an auteur means you're just the latest cishet white dude to be given free rein while other brilliant directors are being gatekept into director-for-hire gigs, does the prestigious distinction actually hold any real value?

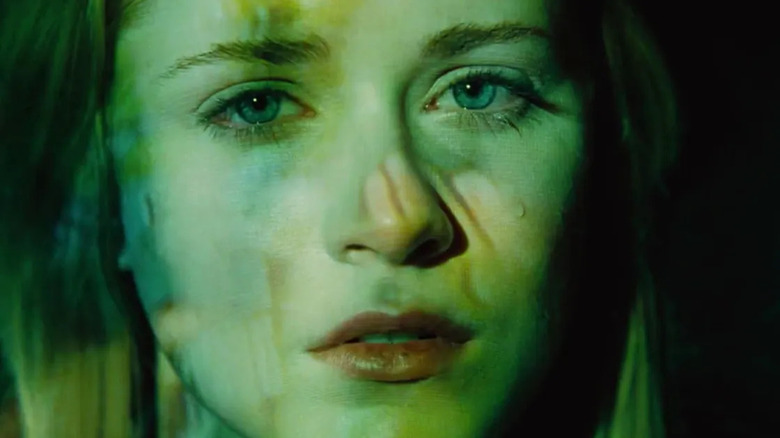

"Beau is Afraid" is the type of inventive madness I love to see, but until more people are given the same amount of freedom to get just as weird with it, it's hard to celebrate Aster's success as anything other than the Hollywood machine working as designed.