How Howard The Duck's Creator Enlisted An Iconic Batman Writer To Help Kill Optimus Prime

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"The Transformers: The Movie" is infamous for one thing above all else: the death of the cartoon series' hero, Optimus Prime (Peter Cullen), leader of the Autobots. Prime dies heroically after a final battle with his nemesis, the Decepticon leader Megatron (Frank Welker), which clears the way for young Hot Rod (Judd Nelson) to rise as the new Autobot leader: Rodimus Prime.

The movie's script was a team effort, and the final product still shows the stitches of revision after revision. The late Ron Friedman is the credited writer; Friedman even wrote a memoir titled "I Killed Optimus Prime." However, others gave input, including Flint Dille, the "Transformers" cartoon's story editor.

As Dille has told many times over the years, he and colleague Steve Gerber were trying to perfect Optimus' death scene. (Gerber, a comic writer who'd created Marvel's Howard the Duck, kept working with Dille as a story editor for "The Transformers" season 3 after the movie.) "We probably rewrote that scene at least five hundred times," Dille once told Topless Robot.

By chance, Gerber was having lunch with a pal from Marvel, so he and Dille asked said pal to pitch in on Prime's death scene. Who was it? Frank Miller, who'd hit it big writing "Daredevil." Miller was then working on the Batman comic that became the character and medium-defining "The Dark Knight Returns." He helped out with Optimus Prime's death, while Dille and Gerber helped Miller crack the climax of "Dark Knight Returns" where Batman fights Superman.

Dille said that Optimus should die like John Wayne as Davy Crockett in 1960's "The Alamo." Miller countered with "The 300 Spartans." (Miller, of course, would retell that story in his 1998 comic "300.") Those influences track with how Optimus' death ultimately played out.

Giving Optimus Prime, and Batman, worthy endings

The opening of "The Transformers: The Movie" shows the Decepticons invading Autobot City on Earth and wiping out many Autobots. Optimus arrives at the 11th hour, and as Stan Bush's "The Touch" hits, he drives into battle, single-handedly defeating every Decepticon in his path to Megatron. The Siege of the Alamo and the Battle of Thermopylae were both hopeless battles where the loser went down swinging. Optimus Prime, without the weight of real history dragging him down, transformed a lost battle into a close victory at the cost of his life.

"The Dark Knight Returns" put Miller in a good place to deliver advice on a hero's death, because that book was written to conclude Batman's story. The comic follows a retired Bruce Wayne in his '50s. He soon becomes Batman again because, in the Caped Crusader's absence, crime and corruption have overtaken Gotham City.

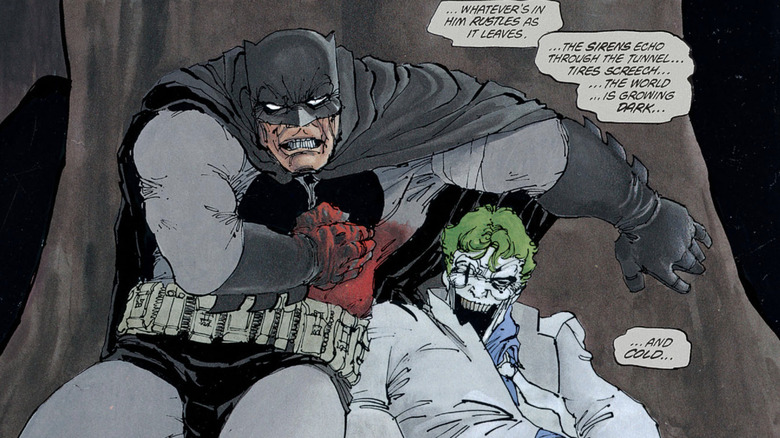

The influence of "Dark Knight" can't be overstated. It and Miller's later book, "Batman: Year One" (drawn by David Mazzucchelli), are the foundational texts of the modern Batman mythos. The simplistic praise they often get is for making Batman a darker character, which is true enough. "Dark Knight" especially features a bloodthirsty Batman, and the book does not sanitize its violence.

Yet, the book is only half a power fantasy; the whole premise is that Bruce is getting old, and even in his physical decline, his obsessions as Batman dominate him. "Dark Knight" brought Batman into the real world by having him age and by showing him confront the political issues of the day like the Cold War. Miller revealed the second Robin, Jason Todd, had been murdered; a dark look at the consequences of making a child into a soldier. For Bruce, though, "the war goes on."

Both The Dark Knight Returns and The Transformers: The Movie feature archenemies' last fight

Legendary comics writer Alan Moore wrote a foreword to "The Dark Knight Returns" called "The Mark of the Batman," where he praised Miller for bringing time to Gotham City. "All of our best and oldest legends recognize that time passes and that people grow old and die," Moore wrote, arguing that no story can be a legend without an ending.

While Dille compared Optimus vs Megatron to Batman vs Superman, the more apt symmetry for me is how "Dark Knight Returns" shows Batman's last battle with the Joker. (That fight happens in a carnival tunnel of love, no less, because Miller is a "subtext is for cowards" writer.) Both scenes show the final, fatal culmination of a previously lighthearted rivalry. The Joker/Megatron would hatch an evil scheme, Batman/Optimus would stop it, rinse and repeat ... but no more.

Introducing death to a conflict unlocks gravitas. In "The Transformers," the Autobots and Decepticons' nonlethal fights can feel like playground squabbling. "The Movie" throws all that pretense out, as if saying "No, this is a war. When they fight, they are trying to kill each other." Young "Transformers" fans weren't prepared for that shift, and ultimately "Transformers" revived Optimus Prime to pacify the angry parents of those heartbroken kids.

Dille said no-one working on the movie had expected such a backlash; they saw Optimus Prime as just a toy. By killing him, they made him something more. As Dille told Topless Robot, "I'd argue that had we not killed [Optimus Prime], we wouldn't be talking about 'Transformers' right now." That was true in 2015 when he gave that interview, and it's still true today. "The Dark Knight Returns," likewise, forever changed how we talk about Batman.