A Martha's Vineyard Resident Kept A Unique Prop From Steven Spielberg's Jaws

Making a movie is an intense experience. The average film shoot takes about three months, and during that time, everyone involved is scrambling in order to make sure that everything and everyone is where they need to be in order to get the shot, with all other considerations secondary. In a working environment where every costume, prop, and set is only as precious as they need to be in order to be used on camera before being discarded, it's a marvel that anything gets saved from a movie shoot. Yet sure enough, lots of little props, scripts, and other knick-knacks get kept as mementos. On occasion, some larger props or set elements of great significance are saved, too. Most everything else is rightfully assumed to eventually be trashed or lost.

Yet every so often, a search turns up bits of cinematic ephemera which even the filmmakers assumed gone forever. That's what happened to Steven Spielberg when viewing the new "Jaws: The Exhibition" exhibit at the Academy Museum in Los Angeles. By his own admission, Spielberg was shocked to discover that someone had kept the ocean buoy from the opening scene of the movie, and that it had thus survived 50 years later to be used as part of the exhibition. As it turned out, the prop's savior was Lynn Murphy, a Martha's Vineyard resident that helped the "Jaws" crew with some of their shooting on the water back in 1974.

While "Jaws: The Exhibition" contains numerous bits of props, notes, storyboards, camera equipment and memorabilia from the making of "Jaws," this buoy is particularly emblematic of how the film beat the odds of its famously harrowing shoot, and became one of the greatest and most influential movies of all time.

Spielberg contends that collectors 'knew something' about Jaws lasting the test of time

According to the story that accompanies the buoy in the museum, Murphy "provided nautical equipment and expertise" to the "Jaws" crew, and helped operate vehicles on the water, which included towing the infamously never-working mechanical shark. Apparently, Murphy decided to keep the buoy that the doomed Chrissie Watkins (Susan Backlinie) briefly holds onto during her shark attack. Murphy took care of the buoy at his home until 1988, when collector Erik Hollander discovered that it was still around and set out to acquire it himself. Apparently, the buoy remained in Hollander's collection until now.

Spielberg himself was amazed that it had been preserved for all these years. As he explained at a press event for the exhibition that this writer attended, he was incredulous that someone — anyone — remembered the buoy:

"From the archives of collectors all over the world who somehow knew something that I didn't know ... When we shot the opening scene of Chrissie Watkins being taken by the shark and we had a buoy floating in the water, how did anybody know to take the buoy and take it home and sit on it for 50 years and then loan it to the Academy?"

Spielberg certainly has a point. He went on to describe how "Jaws" was a movie that he and Universal Studios were genuinely worried at one stage would never be finished, let alone successful. While Peter Benchley's source novel had been a best-seller by the time the film went before cameras, it wasn't quite a sensation on the level of "Twilight" or "Harry Potter," where a rabid fanbase was already planning on keeping and/or reselling memorabilia later. Of course, "Jaws" did go on to make movie history, breaking all sorts of records and inadvertently creating the blockbuster summer movie in the process. Yet that happened months after filming wrapped, so it was indeed prescient of anyone to keep a memento from the set.

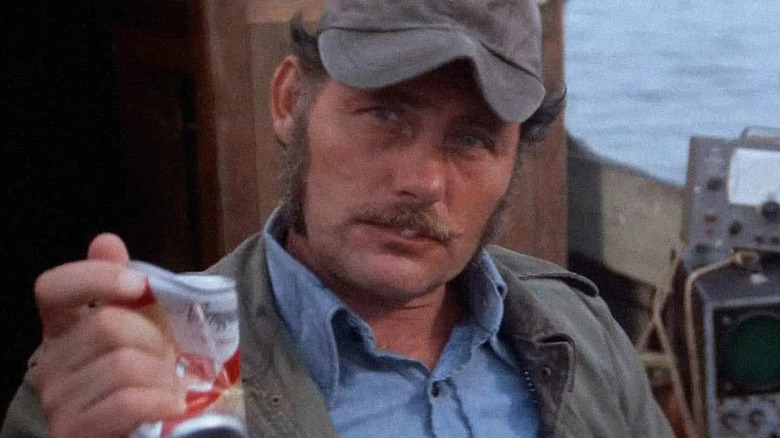

The man who kept the buoy was also an inspiration for Quint

The answer to Spielberg's question may be much simpler and more wholesome than precognition of the success of "Jaws," however. Lynn Murphy wasn't just a native of the Vineyard; he was also one of the men who inspired Robert Shaw's portrayal of Quint. Most of the credit for Shaw's indelible characterization for the shark-obsessed ship's captain tends to go to another Vineyard native, Craig Kingsbury (who played the doomed Ben Gardner in the final film). Yet, according to Matt Taylor, author of the book "Jaws: Memories from Martha's Vineyard" (via the Vineyard Gazette) it was Murphy's voice that Spielberg overheard one day on set and instantly decided that Quint's cadence should match it. Thus, Spielberg instructed Shaw to sound just like Murphy, and the man who was already working as part of the film's crew found himself represented on camera as well as off.

So, while neither Spielberg nor Murphy nor anyone else could've predicted that we'd still be speaking in reverent tones about "Jaws" 50 years later, it's likely that he kept that buoy out of pride of being involved with the creative process of filmmaking. That feeling of contribution and belonging, of being part of a collaboration, is a big reason for the magic of the movies. That magic, in turn, imbues objects like costumes, props, and other assorted things with a resonance that is bigger than themselves alone. A buoy is just a buoy, but, as everyone who sees "Jaws: The Exhibition" will tell you, this buoy is special.