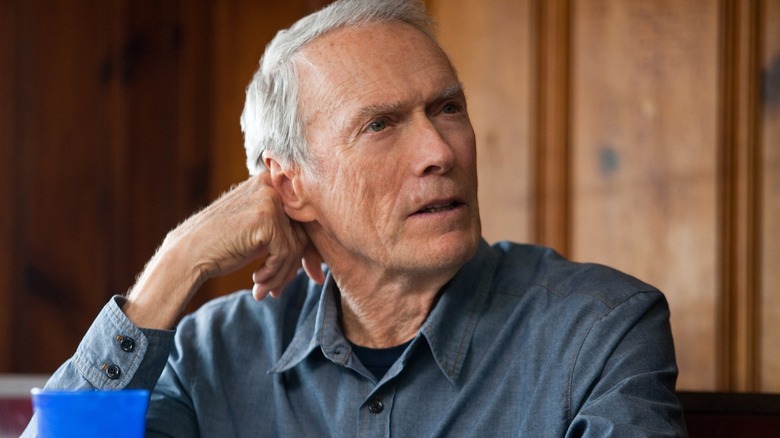

Clint Eastwood Has One Big Rule When Working On A Movie

Clint Eastwood is famous for making films that come in under budget and ahead of schedule. As a director, he likes to move on from a shot after one take (shooting the rehearsal for added efficiency), and doesn't care if this approach ruffles the feathers of someone as prominent as Kevin Costner. Sometimes, Eastwood's get-'er-done approach backfires: I wish he'd taken more time with his amateur actors in "Gran Torino," and would've preferred for him to use a non-plastic baby for a crucial scene in "American Sniper."

When it comes to telling a story visually, however, Eastwood is one of the all-time greats — and he's worked this way since the start of his directing career. Close to 50 years ago, when asked by interviewers Richard Thompon and Tim Hunter about his narrative sensibility, Eastwood, who would go on to win two Best Director Oscars (for "Unforgiven" and "Million Dollar Baby"), said, "I don't like expository scenes, unless they have an important payoff." He's in good company. All-time greats like John Ford, Frank Borzage and Walter Hill famously loathed exposition — i.e. information dumps that bring movies to screeching halt in order to establish backstory and set up the stakes. Done right, films are a show-don't-tell proposition, and Eastwood has worked this way throughout much of his career.

And the man who provided the medium with two of its most iconic characters (the Man with No Name from Sergio Leone's "Dollars Trilogy" and the due-process flouting Dirty Harry) works this way because he believes audiences need to be active viewers.

Clint Eastwood respects the intelligence of moviegoers

Eastwood was preaching my kind of gospel in that Thompson-Hunter interview when he said, "I think they must participate in every shot, in everything. I give them what I think is necessary to know, to progress through the story, but I don't lay out so much that it insults their intelligence. I try to give a certain amount to their imagination. I try to play straight across with the audience."

Interestingly, this may clash with the preferences of today's moviegoers, who prefer a distracted viewing experience where, while scrolling TikTok and the like, they're repeatedly reminded of where the story's headed and what characters are trying to achieve. Art in all of its forms should be about connection, where the elegance of words, images and brush strokes draw the reader/viewer in. And, in Eastwood's view, this approach is about respecting the audience. As he told Thompson and Hunter:

"I hate to have the scene where you take a break, sit down, and tell the audience what's been done up to that point because they're not smart enough to understand it. That's playing down to the audience. As a rule, I always shy away from exposition."

Those scenes are where I check out of a movie, a medium in which you can convey a wealth of emotion in a single, well-composed shot. Even when I'm not crazy about an Eastwood film, I love how he fills the frame with nuanced information. This is not to denigrate the shoot-for-the-edit approach; the best to ever employ this approach (like Tony Scott, Adrian Lyne and Michael Bay) know what they're looking for on set. They just like to find a film in the editing room.

At heart, though, I like a director who despises coverage, which is why Eastwood has always been one of my guys.