15 Horror Movies With The Best Cinematography

The definition of "cinematography" has gotten looser in recent years. Film fans love to praise the way a movie looks — especially lately, when movies often don't look that great! — but in certain corners of online film spaces, "great cinematography" has started to mean "you can take a screencap and it'll look cool as a desktop wallpaper." The popular X account One Perfect Shot, for example, even spawned a TV series about cinematography, but for most of its existence, it didn't actually post shots; it posted frames. A "shot" is a length of film between cuts, often involving movement and change. "Cinematography," then, is more than just a succession of aesthetically pleasing frames. It involves all of the decisions that go into how an image is actually captured — lighting, contrast, movement, and more.

The best directors and cinematographers maintain meticulous control over their images. That becomes especially important in horror films; in here, how we're shown something is often as important as what we're seeing. With that in mind, you'll find examples below where the cinematography is integral to the horror. These are movies that rely on certain aspects of their filming style to heighten atmosphere and tone, perfectly marrying form, function, and fear.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

The classic 1920 film "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari" is a masterpiece of German expressionism (and it also influenced "The Nightmare Before Christmas"). It tells the story of a strange traveling doctor (Werner Krauss) who brings a man in a box to town. He's a "somnambulist," or sleepwalker; at night, when Cesare (Conrad Veidt) emerges from his cabinet and walks the crooked streets, he kills.

"Dr. Caligari" isn't a realist film by any means, and its surreal atmosphere is heightened by its high-contrast cinematography. It's the perfect example of cinematography working hand-in-hand with production design. Thanks to painted sets that emphasize insane, impossible, jagged perspective lines — sets that sometimes have shadows painted directly onto them — director Robert Wiene and cinematographer Willy Hameister were able to suggest a far greater depth of field than the camera is actually capturing. That means the world seems much more vast than the sets would otherwise allow, and because that vast world is full of contrasting light and darkness in ways our eyes are not used to, we feel as though we are watching a nightmare itself.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922)

The 1922 film "Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror" is director F.W. Murnau's adaptation of "Dracula" with the serial number filed off. It follows the basic outline of the classic story we all know — a guy travels to a scary Eastern European castle and inadvertently unleashes a vampire from the old world, a creature who follows him back to a more modern Europe.

Like "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," "Nosferatu" is a film that's visually and metaphorically all about the contrast between light and dark, reflected not only in the story but in the movie's look. In fact, in the movie's most infamous sequence, we are not watching the vampire but instead his shadow. His clawed fingers outstretched, the vampire creeps up the staircase, and we're afraid not just of the incredibly creepy image but of the fact that the actual monster himself is being kept out of frame. Cinematographer Fritz Arno Wagner worked with Murnau to create a film out of images like this, shots where we're afraid not just of what we're seeing, but of what's being left out.

Psycho (1960)

Alfred Hitchcock's daring "Psycho," which netted cinematographer John L. Russell an Oscar nomination, is a film about the horror of randomness. If Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) hadn't made the impulsive decision to steal all that money ... if she hadn't decided to pull off the highway at that particular motel ... if she hadn't decided to shower at that particular moment ... then Marion might have lived.

As a director, Hitchcock always moved his camera in very intentional ways, and camera movement is part of cinematography, too. Opening on a shot of the Phoenix skyline, the camera movement in "Psycho" emphasizes randomness. We pass over building upon building, all filled with rows upon rows of windows, and eventually, we pass through one seemingly at random to find Marion in bed with Sam Loomis (John Gavin). Had that camera chosen a different window, we might be watching an entirely different film.

Similarly, after the infamous shower sequence leaves Marion dead on the bathroom floor, the camera seems unsure of what to do. It tracks across the bedroom to the stolen money, as if the camera itself is saying, "I thought this is what the story was about?!" The movie's cinematography is telling us that we'd better buckle up, because anything can happen.

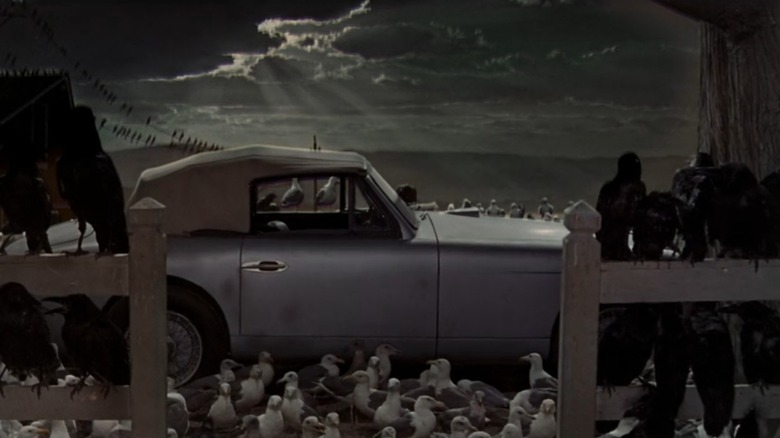

The Birds (1963)

If "Psycho" was about randomness, Alfred Hitchcock's "The Birds" is about the unknowable horror of nature. Humans are powerless against the natural world, the film suggests, and if it decided to turn against us one day, then that would be that.

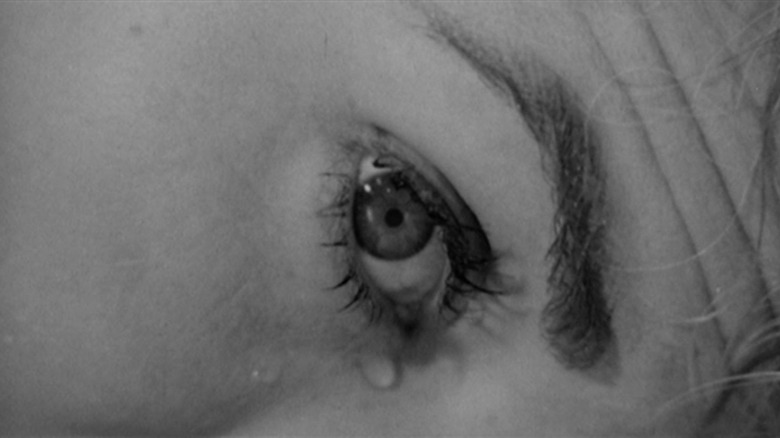

Hitchcock was always finding new ways to film his stories, and "The Birds" is no exception. There are seriously stunning shots in this film, including and especially the infamous "bird's eye view" shot of the tiny town of Bodega Bay. After an incident leads to an explosion at a gas station, Hitchcock cuts to a shot from high overhead; Bodega Bay is sprawled out below, a line of fire tracing a path to our main characters. Slowly, and then quickly, birds fill the frame, their flapping wings and outstretched claws covering up the town.

As in "Psycho," which constructed its shower murder out of a frenzy of editing, Hitchcock and cinematographer Robert Burks use the camera as a participant in the horror. In one sequence, Melanie (Tippi Hedren) finds herself trapped in an attic as birds tear at her face. For a moment, it's as though the camera itself is clawing at her eyes.

Suspiria (1977)

Dario Argento's 1977 film "Suspiria" is about an American student named Suzy (Jessica Harper) who travels to West Germany. She's planning to study at a prestigious dance academy, looking forward to a life in her chosen art form. Instead, she discovers that the world is full of witches, and her dancing may unlock something horrific.

"Suspiria" is a fish-out-of-water story, the tale of a woman in an unfamiliar environment. Accordingly, absolutely everything about the film's visuals is heightened; you've never seen a movie that looks quite like this, because nowhere in the real world looks like this. Argento used lighting masterfully in "Suspiria"; everything is lit in vibrant blues and reds, and the super-saturated colors serve to make things like, say, a pool of blood positively leap off the screen. As she becomes detached from reality, Suzy seems as though she's moving through a dream world; the hyper-saturated cinematography by Luciano Tovoli makes you feel her sense of unease.

Halloween (1978)

John Carpenter's "Halloween" wasn't the first slasher movie, and it wasn't the first horror film to use some of the filming techniques it's often credited with. Still, you could say that "Halloween" perfected the cinematographic tricks first being worked out in slasher movies like "Black Christmas." For example, many such films that followed explicitly reference the opening act of "Halloween," which features a brutal murder shot through the eyes of a young Michael Myers' Halloween mask.

One of the movie's most beautiful sequences comes just before nighttime, as Annie (Nancy Loomis) drives Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) around town at sunset. Cinematographer Dean Cundey shot the sequence largely using natural light from the actual sunset, lens flares and all, and the realistic lighting puts us right in the car with the two friends. It's an idyllic image, conjuring feelings of youthfulness and excitement, and it makes the horror that follows all the more impactful.

That's not to even mention the iconic shot where Michael Myers emerges from the shadows behind Laurie! This is one of those films where, at every moment, how we're shown something is just as frightening as what we're seeing.

The Shining (1980)

The art of cinematography is also the art of framing a shot. Stanley Kubrick was a master of framing, crafting aesthetically-pleasing shots based on the way elements are arranged in the image. That's on full display in "The Shining," Kubrick's adaptation of the Stephen King book about the caretaker of a snowbound hotel going mad. The horror comes from the way Kubrick's images — with an assist from cinematographer John Alcott — emphasize the characters' spatial relationships to one another and their environment.

In some sequences, the characters are kept in the middle of the frame as the Overlook Hotel looms around them. The building seems imposing, frightening, threatening to swallow up their diminutive figures.

Think also, for example, about Wendy (Shelley Duvall) hiding in that closet. Kubrick keeps her in the right of the frame, leaving the closet door taking up most of the image. Jack (Jack Nicholson) smashes through that door with an axe, and his deranged face in the middle of the frame, sticking through the splintered wood, is one of the most indelibly-frightening images in all of horror.

The Cell (2000)

Some people say that cinema is the ultimate art form because it incorporates all the others — sculpture, painting, music, performance, literature, and so on. In crafting film images, then, some filmmakers try to call back to the entirety of art history, making their films into moving artworks that seem like paintings come to life.

One such filmmaker is Tarsem Singh, the man behind films like "The Fall." He's known for painterly shots, crafting films out of stunning tableaux. In "The Cell," a psychological horror film from 2000, Singh and cinematographer Paul Laufer tell the story of a psychologist named Catherine (Jennifer Lopez) who enters the subconscious mind of a killer in order to find a kidnap victim. The killer's subconscious is full of horrific imagery, and "The Cell" turns pain and suffering into art, shooting these scenes as hyper-real, saturated, crisp images full of symbolism.

Admittedly, of all the films on this list, this is the one where you probably could take a screencap of any given frame and have it look cool as a desktop wallpaper ... which is the perfect representation of the twisted mind of an aesthetics-obsessed serial killer.

The Ring (2002)

Gore Verbinski's "The Ring" has evolved into a masterpiece; it set the visual palette for a whole subgenre of J-horror remakes to come. It's a movie about a possessed VHS tape; once you watch it, you have seven days to live before a dead girl crawls out of your television and kills you. Accordingly, this is a bleak, gloomy movie, and the whole thing is lit in a sickly green. While that visual choice has been imitated and watered down over the years, cinematographer Bojan Bazelli achieved it entirely in-camera thanks to lighting choices and filters on the lens; as a result, it looks significantly better than any of its imitators.

After all, "The Ring" is about death, about bloated, decaying bodies left in water. The film's drab coloring suggests the rotted flesh that Samara (Daveigh Chase) will eventually reveal to her victims, leaving them mottled and blanched ... just like the images that make up the movie.

Signs (2002)

Released a year after September 11th, M. Night Shyamalan's "Signs" is about how scary it is to watch something world-changing on television. It's about a family out on a remote Pennsylvania farm; after they find crop circles in the corn, they see on TV that aliens have arrived and are conducting a slow-moving, yet escalating invasion of the planet.

Accordingly, many of the images in "Signs" center around the television. We feel as helpless as the characters; all they (and we) can do is watch the horror happen. In the film's final sequence, the family watches an alien grab Morgan (Rory Culkin). The danger has become all too real, but it's as though the film itself can only understand what's happening if it's mediated by the frame of the television screen; we see most of the ensuing battle play out in reflections, distorted through glasses of water. Finally, Merrill (Joaquin Phoenix) seems to take a bat to the camera itself; unable to look away any longer, the film puts us in the perspective of the alien, as though we're the ones invading.

Under the Skin (2013)

Jonathan Glazer's 2013 film "Under the Skin" is, on the surface, a simple story. Scarlett Johansson plays an alien driving around Scotland in a white van, seducing men to come back to her lair. There, they sink down into black nothingness, and she harvests their skin. Simple!

It's a deeply strange film, one that lives in the closeups of the gorgeous movie star's oddly blank expression. The closeups make her seem otherworldly; whereas closeups usually help us understand a character's interiority by letting us examine their expressions, Johansson here holds her face preternaturally still. In these odd close-ups, she seems empty, a creature of pure motion rather than emotion.

A lot of the Scotland street scenes were shot verité-style, with cinematographer Daniel Landin using handheld cameras that, combined with non-actors, almost suggest a documentary. When we get back to the alien's lair, however, the filming style snaps into something more sleek, more sci-fi, and the contrast heightens the horrific nature of what she's doing there. This is a being we cannot understand; all we're invited to do is watch.

A Cure for Wellness (2016)

Gore Verbinski returned to horror with "A Cure for Wellness," which was sorely overlooked upon release; most critics and audiences were unsure what to make of its strange story involving eels and incest. Odd, Hammer-horror-esque mad-scientist antics aside, "A Cure for Wellness" is one of the best-looking horror movies of the 2010s.

The film reunited Verbinski with cinematographer Bojan Bazelli, and "A Cure for Wellness" is full of images that emphasize scope and scale. For example, a stunning early shot that features an elevated train going through a mountain tunnel; the camera is hanging off the side of the train, and we feel as though we are about to be dropped into the abyss. We are ... metaphorically speaking.

As Lockhart (Dane DeHaan) reaches the wellness facility where the story is set, the images are no less aesthetically pleasing. There are extreme high and low angles, lots of reflections and symmetry, and a recurring visual motif where characters are perched on ledges, silhouetted against the landscape, which is also what's happening on a story level, as the movie is about a man on the edge of his sanity, up against something vast and strange.

Midsommar (2019)

Director Ari Aster was inspired by "The Wizard of Oz" while developing "Midsommar," his horror movie about an American woman who visits a remote Swedish society as they celebrate a twisted summer feast. Visually, in developing the film's look around a world where it's always daytime, cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski recalls the iconic "Wizard of Oz" transition from sepia to Technicolor; Dani (Florence Pugh) moves from a dark and gloomy life back home to a place where the most horrific images imaginable are bathed in sunlight and color.

In some ways, this is a movie about grief. Dani has recently lost her parents and sister in an act of family annihilation, and when she tags along to Sweden with her boyfriend and his friends, who don't particularly like her, it's clear that she's repressing a lot. This movie is about the horror of dragging your grief literally out into the sunlight, staring it in the face in a place where everyone can see what you're dealing with. It's visually and emotionally naked in ways few other horror films are.

Nope (2022)

Jordan Peele's 2022 film "Nope" is a masterful alien-horror movie specifically about the spectacle of capturing horrific, alien images on film. It's about a brother/sister duo (Daniel Kaluuya and Keke Palmer) who realize that something has been lurking in the skies over their farmhouse; they own horses involved in the movie business, after all, so they hope to make a name for themselves by filming proof of what's happening.

To shoot "Nope," much of which takes place at night, Peele and cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema developed new ways of shooting day-for-night. Usually, you'd shoot in the daytime and add a nighttime filter in post-production, but those images don't really reflect how we see darkness. Instead, they set up two cameras with the same lenses, calibrated to capture the same depths of field. One was shot in infrared, however, while the other was shot normally. This allowed them to pull out specific wavelengths of light later, which, when overlayed on the regular image, allowed them to replicate the way our eyes truly see detail at night. The result is some of the crispest, legible nighttime images in all of horror.

The Substance (2024)

Cinematographer Benjamin Kračun shot Emerald Fennell's "Promising Young Woman," which made him the perfect choice to capture the candy-colored, bonkers, brilliant, bloody horror of "The Substance." Director Coralie Fargeat clearly put a lot of thought into the graphic composition of every frame, which is an aesthetic dream as much as it becomes a surreal nightmare.

Just about every frame of "The Substance" is spectacular. From the shot of a yellow egg on a blue table that opens the movie, to the film's colorful hallways, stark-white bathrooms, and buckets of bright-red blood, this is a movie that understands that it's the images that tell the story. It's about an aging actor named Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) who takes an experimental injection to split into Sue (Margaret Qualley), a younger, more perfect version of herself ... but the movie is also about the specific yellow shade of her coat, and the specific pink of Sue's bathing suit. It's about the facade we put on to hide ourselves from the world, about how freeing it would be to shed it all, and about how horrific it is that we even care.