Why Life Of Chuck Plays More Like A Christopher Nolan Movie Than Stephen King

This article contains spoilers for "The Life of Chuck."

In 1843, the Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard wrote in his journal a passage which has echoed throughout time ever since, albeit one which is often shortened for easier consumption. The abridged and paraphrased quote is: "Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards." The full passage laments the paradox inherent within this axiom:

"It is really true what philosophy tells us, that life must be understood backwards. But with this one forgets the second proposition, that it must be lived forwards. A proposition which, the more it is subjected to careful thought, the more it ends up concluding precisely that life at any given moment cannot really ever be fully understood; exactly because there is no single moment where time stops completely in order for me to take position [to do this]: going backwards."

While it's obvious that there's no literal way of stopping, reversing, or otherwise manipulating the actual flow of time to closely and accurately examine our lives, human beings have found the next best thing: art. While some artistic mediums excel at capturing the present in an electrifying way (namely, live theatre), most can lightly defy the flow of time. Painting, music, literature, and cinema all manage to both address the present while existing for long after their initial creation, allowing their messages to speak to numerous generations and even grow deeper and more layered as a result. While the study of history is important to try and suss out the facts of our lives, art is important to try and find the truths.

Some artists go a step further than most, realizing that their ability to create and tell stories within certain mediums doesn't have to follow the usual linearity. Author Stephen King utilized this possibility when writing his novella "The Life of Chuck" in 2020, and filmmaker Mike Flanagan has retained King's unique story structure for this year's film adaptation. While the concept of a story told non-chronologically is nothing new, the way that King and Flanagan tell "The Life of Chuck" recalls the work of Christopher Nolan. Both "Chuck" and several of Nolan's films utilize non-linear narratives as a way to best enhance a story's themes rather than as mere gimmickry.

'The Life of Chuck' and Nolan's films understand the cumulative joy of puzzle-solving

In general, non-linear narratives are employed in order to achieve an average narrative device in a new and unique fashion. For example, many films have been structured non-linearly to disguise a twist in the story, or, as with Quentin Tarantino's "Pulp Fiction," to figuratively but not literally resurrect a dead character, and so on. The way that Christopher Nolan plays with linearity in his films features these tropes, but also makes the act of watching the film feel like solving a puzzle in real time, too. It's this aspect that Flanagan also employs in "The Life of Chuck."

Nolan's films often teach the audience how to watch them as the movie is unfolding, whether it's through context clues (such as in "Following" or "Inception") or through on-screen signifiers (such as in "Dunkirk" and "Oppenheimer"). Unlike Nolan's "Memento," which featured two concurrent timelines (one structured in reverse, the other moving forward in time), "The Life of Chuck" is relatively simpler, with the story divided into three chapters presented in reverse chronological order. Yet this isn't done merely to turn the usual character study structure of birth to death (also referred to as "womb to tomb") on its head, but to allow each segment to have a resonance it may not have had if they'd been arranged linearly.

As simple or complex as the cinematic puzzles may be, there's a unique joy in being rewarded for paying attention. It makes the viewer feel (albeit in a less grand fashion) the same sense of accomplishment a detective or researcher might feel. In the case of "Chuck," the reverse chronological order seems akin to how any of us examine our own lives: the most recent events come to mind first, with bigger revelations (but still some mystery) to come the further back we go.

Flanagan and Nolan allow the audience to share the protagonist's perspective

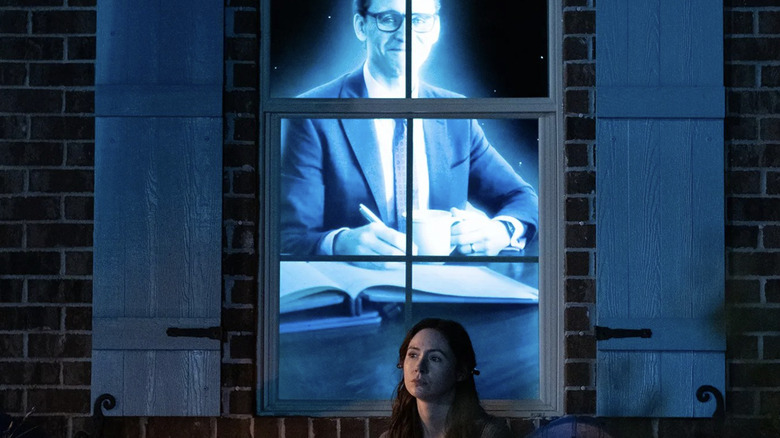

Of course, the biggest effect that both Nolan and Flanagan are looking to impart with using non-linear narratives is putting the audience in the point of view of the character (or characters, as the case may be). "Memento" isn't structured the way it is simply to obfuscate the plot and its details, but also to allow viewers to feel as unsure about things as Leonard Shelby (Guy Pearce) does at all times. In "The Life of Chuck," each chapter is set in a different period in the life of Charles "Chuck" Krantz (played at various ages by Tom Hiddleston, Cody Flanagan, Benjamin Pajak, and Jacob Tremblay): his youth, his middle age, and his passing, in reverse order. The full power of the segment surrounding Chuck's death, however, would be robbed if we were seeing the film in chronological order.

Instead, as an opening segment, the emotions surrounding the characters of Marty (Chiwetel Ejiofor), Felicia (Karen Gillan), and others can resonate harder when we're experiencing events from their point of view. Once it's revealed that they're facets of Chuck existing inside his memory world within himself, and how their universe (which, again, is the real Chuck) is dying, the moment carries much more emotional, dramatic, and thematic weight than it might have in the "correct" order.

Even when that twist is revealed a third of the way through the film, "Chuck" has more surprises in store, if only because the following two segments help flesh out the interior and exterior story of this character. Seeing these small — but momentous — events in Chuck's life feels akin to how Nolan presented the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as not a simple and linear story but one which found the man continually torn between the secrets of the universe he unlocked and their devastating, irreversible consequences. In another biopic or character study, we'd be more likely to ascribe succinct emotions and thoughts to someone as we travel through events with them, but the non-linear approach allows for a more compelling ambiguity. "Chuck" wishes to ask whether a road not traveled is cause for regret or simply a part of fate to be embraced, and it can't do so without using the time-bending power of cinema.

Was King, the pop-culture maven and cinephile, inspired by Nolan's films when writing "Chuck?" The story certainly feels unique to the author, even considering his non-linearity as seen in "It." The possibility is there. Whatever the case, it's wonderful that Flanagan chose to keep the structure intact, as it makes the film, like Nolan's work, feel that much more resonant, intellectual, philosophical, and, of course, moving.