In Oppenheimer, Everything Is Shades Of Grey (Even When It's In Black And White)

This article contains spoilers for "Oppenheimer."

At this point in Christopher Nolan's career, the director's name might as well be synonymous with the concept of ambiguity. In addition to making a number of mind-bending movies, all of Nolan's films bear the hallmark of the auteur's obsession with the power cinema holds over the fourth dimension (also known as "time" for those of you who haven't brushed up on your Einstein), the medium having the ability to extend or compress everything from a single moment to several lifetimes.

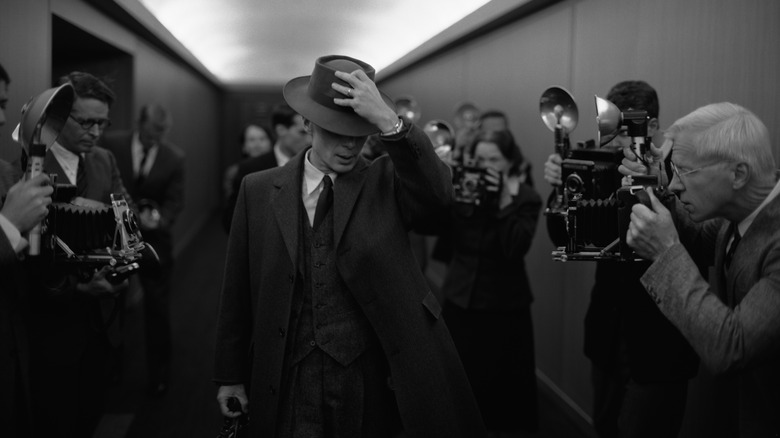

His wife and producer, Emma Thomas, points out in the official press kit for her husband's latest film, "Oppenheimer," that Nolan has "always been fascinated by subjectivity and objectivity," and that "Oppenheimer" is no exception. The film, a biopic of the infamous creator of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer (played by Cillian Murphy), is written by Nolan and based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin's 2005 biography entitled "American Prometheus." Most biopics involve a framing device in which the central character is invited to reflect back on their life, and while that device is in "Oppenheimer," it's not used in straightforward, linear fashion.

Throughout the film, Nolan presents scenes shot either in color or black and white. Instead of this disparity signaling a change of time period, the difference stands instead for scenes presented subjectively or objectively. Yet, this being a Nolan film, even the "objective" scenes can't be truly called such, as they're primarily from the point of view of a man who had huge issues with Oppenheimer, Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.). It's a quintessential bit of Nolan cheekiness that even the black-and-white scenes are not really in "black and white."

It's black, it's white, it's tough for Nolan to just be that

Of course, "Oppenheimer" is not the first instance of Nolan using black and white photography. His very first film, "Following," is fully shot in black and white, and the reason for this is partially due to budget: the movie was a fully independent production, and was shot on 16mm film over a series of Saturdays for a full year due to cast and crew needing to work full-time jobs during the week. The other reason is that, since "Following" is a neo-noir with a non-linear structure, this use of black and white is both a nod to noir tradition and a winking contrast to the film's ambiguity.

Nolan's follow-up feature, "Memento," continued the filmmaker's interests in neo-noir and non-linearity, as the film famously follows a backwards structure where each succeeding scene takes place prior to the one just viewed. However, that's only half the story; while Nolan shoots the backwards scenes in full color, there are scenes shot in black and white that progress in normal linear fashion, eventually revealed to be flashbacks to events prior to when the color scenes begin. Given that "Memento" is the story of a man who's been stricken with a rare memory defect that doesn't allow him to make new memories past a certain point in his life, this structure as a whole gives audiences a fully subjective experience, putting them in the character's place.

Or does it? Nolan also loves ambiguity, to the point where the commentary track he recorded for "Memento" features alternate endings wherein the director gives conflicting answers as to the mysteries within the movie. The black and white is thus revealed as being another layer of ambiguity beneath supposed clarity, a visual shorthand for truth or reality that is itself made suspect.

A tale of two hearings

Unlike the non-linear experiments of Nolan's early work, "Oppenheimer" is a little more straightforward, depicting events in the theoretical physicist's life from the 1930s to the 1950s in between two anchor points, both of which were hearings: Oppenheimer having his Atomic Energy Commission security clearance reviewed in 1954, and Strauss' confirmation to the Senate being considered in 1959. Although they're hearings, they hew much closer to being like trials, with each man cross-examined and having their true motives called into question.

Nolan recently explained the difference between the color and black and white to AP News:

"I knew that I had two timelines that we were running in the film. One is in color, and that's Oppenheimer's subjective experience. That's the bulk of the film. Then the other is a black and white timeline. It's a more objective view of his story from a different character's point of view."

That "different character" is of course Strauss, and the black and white scenes do indeed present Oppenheimer in a different light from the subjective color scenes: in color, Oppenheimer is a brilliant, ambitious, and troubled man, while in black and white, he seems far more arrogant, judgmental, and suspicious. In this way, the device allows Nolan to retain a good deal of ambiguity about his subject, not presenting the father of the atomic bomb as either a wholly misunderstood great guy nor a monstrous egotist.

Yet there's the added wrinkle of the black-and-white scenes not being wholly objective, either. While it presents a different Oppenheimer, it's an Oppenheimer viewed through the perspective of Strauss, a man who envied and resented Oppenheimer as well as suspected (or at least led others to suspect) him of being anti-American. It's Nolan once again using black and white as a subversion, presenting ambiguity in the guise of objectivity.

Fission + fusion = destruction

There's yet another layer to the way "Oppenheimer" uses its color and black and white scenes, which lies in the on-screen titles demarcating them and the way they comment on one of the movie's major themes. Right from the start of the film, Nolan labels the color and black and white scenes: "1. Fission" for color, and "2. Fusion" for black and white. This helps orient the audience with regard to the stylistic change and signals that there are bigger reasons for it.

At first, this distinction seems to be similar to Nolan's prior World War II-era feature, "Dunkirk," which used similar titles to distinguish between three separate timelines operating over different lengths. True to form, "Oppenheimer" isn't a strictly linear movie, jumping around between time periods at will as well as between color and black and white perspectives. This time around, however, Nolan isn't experimenting with structure as much as he is with point of view, utilizing the movie's timelines as fission and fusion, two disparate reactions that achieve similar results.

Those results are, of course, highly destructive and damaging, resulting in permanent change that cannot be reversed. It turns out that this is the fate most feared by Oppenheimer, not just in terms of potential nuclear destruction but in terms of his part in creating a world where that potential even exists. As Nolan depicts in the film, Oppenheimer is tortured by the possibility that testing the atom bomb could result in a chain reaction that sets the entire planet on fire, and even though it doesn't literally happen, Nolan posits the idea that maybe it did in another fashion. Due to a world in crisis, a nation looking to use that crisis to assert dominance, a populace brainwashed by militaristic propaganda and jingoism, one man's almost willfully blind obsession and another man's petty grievances, the threat of nuclear destruction arrived and is here to stay — what that means and how you feel about it is likely not so black and white.