Why James Cameron Insisted On Aliens' Down-To-Earth Dialogue

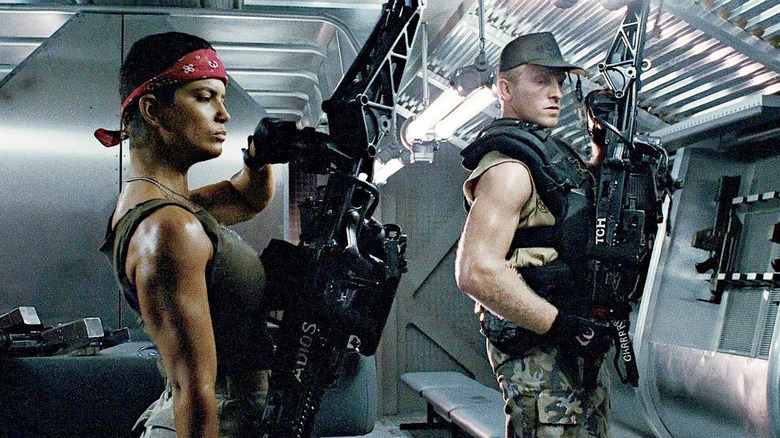

James Cameron's horror sequel "Aliens" has some of the most quoted lines of any blockbuster movie. To this day, fans tell each other to "stay frosty," and "Game over, man!" has become a pop-culture fixture repeated around the world. Starting with survivor Ripley (Sigourney Weaver), Cameron expands the players of Ridley Scott's 1979 film "Alien" to include gun-toting Colonial Marines who look forward to engaging with the same sort of alien xenomorphs that decimated the Nostromo crew. They insult each other just enough to make it believable that they would actually die for one another later on when the bullets start flying. Through their fictional grunts of the future, their dialog echoes the language of American soldiers past, what critic Jean-Marc Lofficier characterizes as "'Hellcats of the Pacific' in space."

Cameron explained his decision to opt for realism over futuristic techspeak with Lofficier, saying:

"The sense of the dramatic relationships from these 1940s, 1950s war films, which sort of portrayed the common soldier, was more what I was looking for. The dialog itself, the idiom, is pretty much Vietnam era. It's the most contemporary American combat "warspeak" that I had access to. I studied how soldiers talked in Vietnam, and I took certain specific bits of terminology, and a general sense of how they express themselves, and I used that for the dialogue, to try and make it seem like a realistic sort of military expedition, as opposed to a high tech, futuristic one. I wanted to create more of a sense of realism rather than that of an interesting future."

That said, any future wherein soldiers still say "F***in' A" is an interesting one.

Think of it like a futuristic TV set, Cameron says

On the exomoon LV-426 where the Marines are dispatched to meet a nasty foe, they work under the guidance of one Sergeant Apone, played by veteran Al Matthews. Matthews' experience — he calls it "Vietnam syndrome" in the "Aliens" making-of documentary — lent an air of realism to his castmates' performances by promoting things like trigger discipline on the set, whether their weapons were props or not. Matthews was right at home in the language written for Apone, who greets his soldiers as "sweethearts" and speaks with the booming cadence of a take-no-guff noncommissioned officer.

In his interview with Lofficier, Cameron elaborated on how crucial the dialogue is for audiences, even when watching something set centuries ahead of them. "It's like the idea that, perhaps, 150 years from now, television sets may not even remotely resemble what we know as video today," he said. "We don't know what it will be, but it will be something different. And whatever it is, it will be familiar to those people, but if we were to walk into a room, we would very likely not recognize it for the equivalent of a TV set."

"If you're trying to create a textural reality within a film," Cameron continued, "you can't go to the extreme of suggesting what technology will be like. You have to keep it one step beyond what it currently is, but no more, so that you can look at it and say, 'Right, that's a TV set! It's a futuristic TV set, but I know what that is.'"

Whether it's "asses and elbows" or the simple touch of a solider shouting "say again" (rather than some form of "repeat" as a sci-fi movie might do) into the comms equipment, "Aliens" gets its soldiers right before everything goes irrevocably wrong.