Aliens' Queen Had One Advantage Over The Original Xenomorph

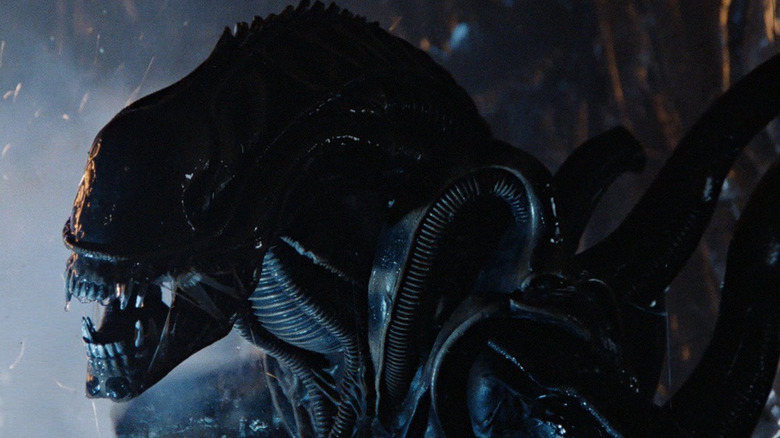

James Cameron's "Aliens" does everything that a sequel is supposed to do; every component of the sci-fi classic is bigger and badder, from the firepower to the foes. Picking up from Ridley Scott's 1979 sci-fi horror "Alien" required more than just showing more extraterrestrials. The setting expanded from the lonely space vessel the Nostromo to the exomoon LV-426, its human colony wiped out by an unknown organism. Viewers knew what kind of specimen annihilated the terraformers at Hadleys Hope, having been introduced to them seven years prior. A concept poster for "Alien" alluded to a creature "so terrifying, they only exist in a nightmare ... or outer space," fulfilled by H.R. Giger's part-organic, part-mechanical designs. The result was the xenomorph, with its phallic head designed by Carlo Rambaldi, and its towering frame embodied by the 6-foot-10-inch tall Bolaji Badejo.

Cameron, who concurrently penned a draft for a Rambo sequel while writing "Aliens," was equipped to broaden the story's scope. Under the supervision of John Richardson, a 40-person crew cultivated the creature effects at Stan Winston Studio, crafting facehuggers, warrior xenomorphs, and a monstrous alien queen to birth and command them.

Speaking with Jean-Marc Lofficier, Cameron echoes the classic horror filmmaker's hurdle: a believable, scary monster that doesn't just look like some actor in a creepy onesie costume. Here, the Queen had an edge.

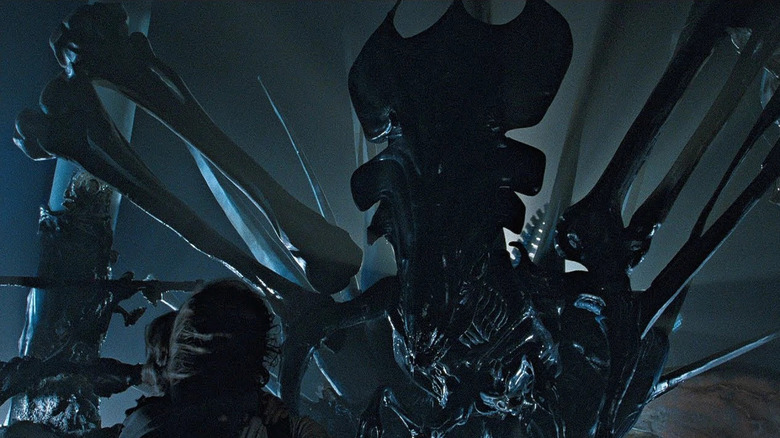

"I think we had the advantage of her not being exactly an anthropomorphic figure, so she obviously is not a person in a suit. Your willing suspension of disbelief is aided by the fact that it's clearly not a performer in a suit. On one hand, you know that it's achieved by a sort of puppeting technique, but the fact that you also know that it's not just a person dressed up immediately helps you perceive it as a living creature."

You can't be too in love with the effects

Cameron's Queen, designed between the director and Stan Winston, is a special lady. Using H.R. Giger's alien designs as a template, the "Aliens" Queen retains much of the Swiss artist's too-hot-for-the-studio biomechanical aesthetics. Metal, flesh, sinew, and exoskeleton amalgamate to create a horrifying psycho-sexual nightmare just as vicious as its '79 predecessor. As Ash observes (a little too admirably), "its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility." Acid blood courses through its body. It moves with reptilian speed and grace. Its lack of visible eyes competes with its full-frontal teeth that can only bare themselves and attack.

Through a long creative process, the Queen had all of this, plus the ability to reproduce, and a new sense of vengeance (her babies were set aflame, after all) not seen in Scott's "Alien." Sporting an extra set of arms and a fabulously regal head crest operated through a Frankensteinian fusion of animatronics, puppetry, and crane support, the Queen was a successful expansion of the cosmic-gothic bits and bobs that made the original alien creature so spine-chilling. But just because the effects were rad doesn't mean that they needed showcasing. Quite the opposite, in Cameron's mind:

"You have to be not too in love with the effects, if you see what I mean. I understand why some directors choose not to hide the special effects work. They try to make it so compelling that it looks real under normal everyday conditions. But I think it's one of those logic traps. You become so enamored of the illusion that the story is no longer what's important."

Long live the Queen

With more aliens getting screen time — enough of them to exhaust four automatic sentry guns packing 500 rounds apiece — one might fall into the pitfall of giving them top billing and a spotlight to match. In the "Aliens" making-of documentary, creature effects coordinator Tom Woodruff Jr. highlights Cameron's vision that worked for "Aliens" as it had worked for John Carpenter's "Halloween" — it's so much scarier when you can't see the whole thing for too long.

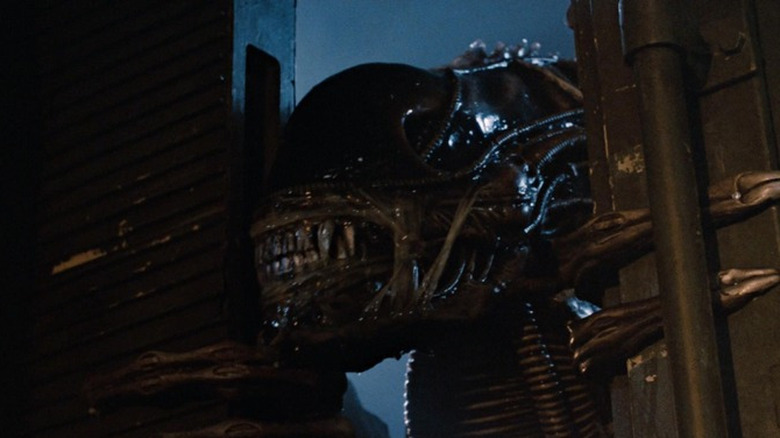

"Cameron knew exactly how he was going to shoot these things and knew it was going to be an interplay of shadow and light on these things ... just seeing the movement of living creatures coming out of the dark and into the light, moving through the light, and never really focusing or never really studying them. That was directly connected to the fact that there were hordes of aliens this time, and not just one that we were focused on."

And so the aliens flit in and out of alcoves, obscured by sprinkler systems, emergency lights, and steam-filled corridors. Anyone who watches the later "Alien" sequels can attest to the diminishing impact of the xenomorphs and their variants. They even swim onscreen like Esther Williams in one of the lesser-celebrated chapters. No, the xenomorphs -– and their Queen –- leave the greatest impression when treated something like Carpenter's Michael Myers (not so much in the later iterations), or Alan Arkin's black-clad Harry Roat Jr. in "Wait Until Dark," where the menace emerges from murky corners, offering only a vague sense of what you're dealing with.