Cary Grant's Reputation Was A Reliable Tool For Alfred Hitchcock

Watch enough Alfred Hitchcock movies and you'll start to notice familiar faces, including some of the most famous ones from Hollywood's golden age. One of them is Cary Grant; during the 1940s and '50s, Hitch worked with Grant four times.

Of course, "Cary Grant" was as much a character as any of the ones that the actor born Archibald Leach played in his films, directed by Hitchcock or otherwise. Leach said of his star persona, "Everybody wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant." Graham McCann's biography "Cary Grant: A Class Apart" explores how Leach became Grant and, true to its subtitle, the distance between his working-class roots and later life as Hollywood royalty. The book also details how Hitchcock wielded this crafted screen persona in the four movies he directed Grant in.

Cary Grant in Suspicion

Hitchcock and Grant's first collaboration, the 1941 thriller "Suspicion," is a spin on "Rebecca," Hitchcock's American debut from the previous year. In both, Joan Fontaine plays a woman who suspects her new husband is a murderer. In "Suspicion," though, the roles of class are reversed — Fontaine is not an ordinary woman wed to an aristocrat, but an heiress charmed by a broke hustler.

Sir Laurence Olivier, who starred in "Rebecca" as Maxim de Winter, was a different type of actor from Grant. He'd come up playing Byronic heroes in Shakespeare classics; casting him as the character who audiences are supposed to suspect is a villain makes sense. What's daring about "Suspicion" is that Hitchcock slots Grant into that role. Grant always charmed as a leading man due to his natural instinct for comedy, and now audiences were supposed to think him cold-blooded.

Grant's character, Johnnie Aysgarth, can't quite compete with the brooding de Winter. Still, he's compelling as an outgoing gambler who tells so many lies he speaks them as if they're true. According to McCann, Hitchcock's goal with the character and film was to expose the root of Grant's star appeal in a more sinister light.

Charm hiding danger

In "Suspicion," Lina McLaidlaw (Fontaine) marries Grant's Aysgarth after being swept off her feet. She soon learns of his financial problems and that he has no ambition beyond gambling. As the lies and bodies pile up, Lina suspects that Johnnie intends to murder her for her inheritance. McCann writes:

"Hitchcock had wanted Grant for the role precisely because of such audience expectations. He knew that audiences on seeing Johnnie Aysgarth would know that he was Cary Grant, so that however bleak the situation might become, they would not believe that a character played by Grant could really turn out to be a murderer. Hitchcock, therefore, planned to execute an audacious double-bluff, revealing Grant's character to be as bad, as cold, as evil as he had seemed to be, thereby administering a shock far beyond anything that the plot itself could have been expected to deliver."

Hitchcock's ending was in line with the source material, Anthony Berkeley Cox's "Before the Fact." Originally, Johnnie would Lina a poisoned glass of milk, which she drinks, knowing it's poisoned. What Johnnie doesn't know is that she's already written a letter exposing him as her murderer. But this isn't the ending we got.

In the final cut it turns out Johnnie is not a murderer — he was considering poison as a way of escaping his debts via suicide. The couple drives off into the sunset, facing an uncertain but optimistic future — a definite clunker of an ending. Per McCann, Grant himself "thought the [original] ending was marvelous. It was a perfect Hitchcock ending. But the studio insisted that they didn't want to have Cary Grant play a murderer."

Note how Grant refers to himself in the third person, with movie star "Cary Grant" as a separate being from himself.

Later roles

Two years after "Suspicion" Hitchcock made "Shadow of a Doubt." This was another riff on the "Rebecca" formula; a young woman suspects a man close to her of sinister intent. Only this time, the betrayal is a paternal one, not romantic; Charlie (Teresa Wright) discovers the uncle for who she is named (Joseph Cotton) is a serial killer. Why was Hitchcock able to bring "Shadow of a Doubt" to its proper conclusion but not "Suspicion?" Simple, Cotton was a character actor (albeit one with leading man looks); playing a villain wouldn't betray, or subvert, his screen persona like it would Grant's.

Hitchcock used Grant in different ways in each of their subsequent collaborations. In "Notorious," he's a more straightforward hero and romantic lead. There's more of an edge to his performance in "To Catch A Thief," but even though John Robie is a gentleman thief, we're never supposed to be wary of him like we were Johnnie Aysgarth.

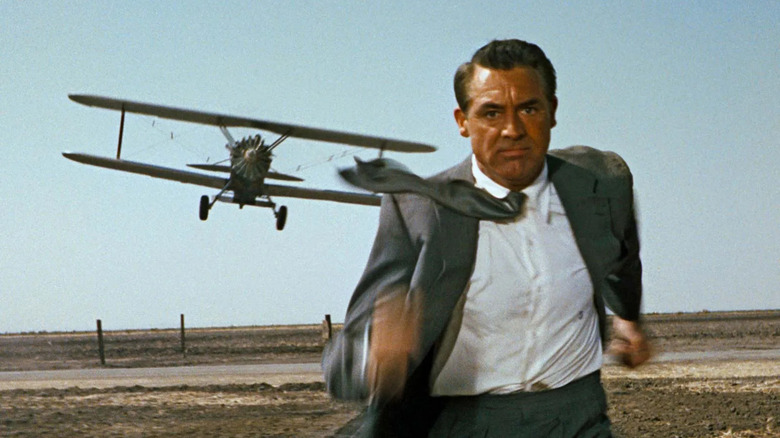

Only in their fourth and final collaboration did Hitchcock decide to bring Grant's talent for comedy front and center. His character Roger Thornhill in "North by Northwest" is defined by befuddlement, drawn into a global conspiracy and left totally out of his depth. Yet somehow he always walks away, no matter how many attempts are made on his life. Grant's casting is the punchline of "North by Northwest"; Hitchcock made the actor who every man in America wanted to be into an everyman.