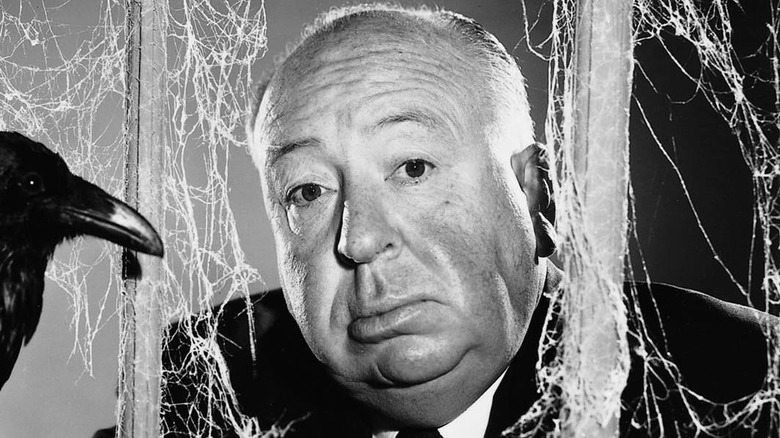

Alfred Hitchcock's 20 Best Films Ranked

With a career that spanned over 50 years, Alfred Hitchcock is an undisputed master of cinema. With around 55 feature films on his resume, it is extremely hard to narrow them down to a list of 20 — and that's before you even get to ranking them.

Hitchcock charted the political turmoil of the 20th century as it was unfolding; with his pre-war espionage thrillers "The 39 Steps" (1935) and "Sabotage" (1936), his examinations of the effects of World War II on the human condition in "Lifeboat" (1944) and "Notorious" (1946), and his takes on the Cold War in "Torn Curtain" (1966) and "Topaz" (1969). He worked with some of the most iconic stars of the Golden Age of Hollywood time and again, including James Stewart, Cary Grant, Grace Kelly, and Ingrid Bergman.

While Hitch is best known for horror and thrillers, there is a strong core of romance in much of his work, although we all know how twisted his love stories could get. So, let's start this tour through 20 of Hitchcock's best films, which span the '20s through the '70s, and which hopefully provide a good overview of what makes Hitchcock the Master of Suspense.

20. Dial M for Murder (1954)

Intricately-plotted thrillers with satisfying endings are perhaps what Hitchcock does best, and this Grace Kelly vehicle is no exception. I've been lucky enough to see "Dial M for Murder" in a theater in 3D, as it was originally intended to be viewed. While this may sound strange, trust me, it's a memorable experience.

Kelly plays a wealthy socialite who's sleeping with a crime writer, Mark Halliday (Robert Cummings). When her husband Tony (Ray Milland) discovers the affair, he hatches an elaborate plan to have her killed so that he can inherit her money. When the plan goes awry, he frames her for murder instead, hoping that she'll be sentenced to death.

Like many of Hitchcock's best films, including "Rope," "Dial M for Murder" is based on a play. Actor John Williams even reprises his stage role of Inspector Hubbard, a Sherlock Holmes-style detective who is smugly a step ahead of everyone else, and who delivers his "gotcha" moment at the end with aplomb. Although filmed at Warner Brothers' studios in Hollywood, "Dial M for Murder" is set in London, and Hubbard's stereotypical English detective only works in this setting.

As in "Rope," the characters' movements are carefully choreographed — almost the entire film takes place in the same room — and masterfully controlled by the director. "Dial M for Murder" may be over-the-top, but it's a fun Hitchcock film with a great denouement.

19. Foreign Correspondent (1940)

This espionage thriller, set in Europe on the brink of World War II, is notable for many reasons, not least of which is that it contains the best character name in any Hitchcock film: Scott ffolliott (played by the always magnificent George Sanders). Joel McCrea stars as John Jones, the titular correspondent, who is sent from the U.S. to Europe in 1939 to report on the escalating tensions between nations.

The first half of the film is better than the second, with some classic Hitchcock set pieces, including an assassination scene that unfolds amongst a sea of umbrellas and the assassination attempt on the top of Westminster Cathedral. Like all the best Hitchcock films, there is a romantic undercurrent, as Jones falls immediately in love with Carol Fisher (Laraine Day) and proposes to her during a dramatic storm at sea.

Once again, it's a marvel that a film made in 1940 could have so much to say about American neutrality and treasonous spies during a war that had barely begun. It's an ambitious film, too. It's set across several countries, features diverse locations like an isolated windmill and a flying boat, and is dynamically shot in a style similar to Hitchcock's other spy thrillers, including "North by Northwest." This is a lesser-known Hitchcock film that is well worth seeking out.

18. The Trouble with Harry (1955)

Absolutely bursting with gorgeous autumnal color, this comedic farce centered on an inconvenient dead body was Shirley MacLaine's impactful debut. Four unconnected residents of a small Vermont town are all convinced that they have caused the death of Harry, the body found lying in the hills nearby. While considering how to keep the death secret from the authorities and how to dispose of the corpse, romance blossoms between both the younger couple and the older one.

Edmund Gwenn gives a brilliant performance as Captain Wiles, one of the townspeople who becomes embroiled in this macabrely funny and increasingly ridiculous scenario. There's no reason why a "throwaway" comedy should have such stunning visuals, but "The Trouble with Harry" is comparable to Douglas Sirk's "All That Heaven Allows" for being one of the all-time great fall-set films.

"The Trouble with Harry" was the first collaboration between Hitchcock and composer Bernard Hermann, and the score keeps the tone fast-paced and light-hearted. MacLaine's unusual acting style is apparent from the jump — we can already see the beginnings of Miss Kubelik (her character in Billy Wilder's "The Apartment") in her unconventional line delivery and her dreamy, breezy quality.

While Hitchcock will always be best-known for his thrillers and horror films, a rich vein of dark humor runs throughout his work, and it really gets a chance to shine here. "The Trouble with Harry" is a hidden gem on Hitchcock's filmography.

17. Lifeboat (1944)

"Rear Window" and "Rope" famously take place in single, confined spaces, but many people don't realize that Hitchcock had already pushed this idea to an extreme in "Lifeboat," a 1944 World War II film. While the titular boat's Allied crew, which includes war photographer Connie Porter (Tallulah Bankhead), tries to survive by rationing their food and water, most of the film's tension is caused by the presence of a German U-boat captain who the passengers rescue from drowning. The Brits and Americans argue about how much they can trust him, and wonder if they should push the man back overboard.

"Lifeboat" is filled with devastatingly heart-breaking characters, including a suicidal woman whose baby has died, and a sweet-hearted man played by William Bendix who must have his leg amputated. Hume Cronyn, who also appeared in "Shadow of a Doubt" plays another member of the lifeboat's crew. The acting is impressively understated across the board, and has a real emotional impact.

The ending goes a little over-the-top and veers into histrionics, but up until this point, "Lifeboat" is a gripping World War II drama that is a great addition to the niche genre of lost-at-sea movies. Bankhead plays a feisty lady who doesn't lose her moxie despite the unusual circumstances. This film is proof that when Hitchcock steps back from intricately-plotted, high-concept fare, he can still make an extremely compelling film.

16. Marnie (1964)

As controversial and psychologically complex as "Vertigo," this film starring Tippi Hedren and Sean Connery starts similarly to "Psycho," with a woman stealing a large sum from the company safe and fleeing. Marnie (Hedren) suffers from nightmares, which can be triggered by the color red and thunderstorms, and struggles with physical intimacy. This film contains several shocking elements, including coercion into marriage and marital sexual assault, while somehow not turning us completely against the perpetrator.

"Marnie" explores PTSD, repressed memories, and childhood trauma, as well as a woman's desire to escape her life before emotional entanglements get too deep. Both Marnie and Connery's character, Mark, are morally complex — they're not two likable people who we're unquestionably rooting for. Right up until the very end, it's not clear if it's better for them to be together or apart. Viewers are likely to be left feeling extremely ambivalent and frustrated, which is why "Marnie" gets such mixed reactions to this day.

The story also features a complicated mother-daughter relationship, one in which things are not as they first appear. It is absolutely understandable why people struggle with "Marnie," especially when you factor in what was allegedly happening off-screen between Hitchcock and Hedren. But I can't help but be fascinated that such a film exists at all, let alone that it was made in the '60s and stars a newly-cast James Bond. It's an extremely interesting film, if not an especially enjoyable one.

15. Frenzy (1972)

"Frenzy" saw Hitchcock return to his native London for the first time since 1950's "Stage Fright" (apart from the climactic scenes of "The Man Who Knew Too Much" in 1956). It is interesting to see Hitch collide with '70s cinema, even though it was destined to only happen twice. "Frenzy" begins with a body washing up in the grimy Thames and continues its sleazy, gritty '70s feel throughout. Comparing the graphic strangulation scene in this to something like the shower scene in "Psycho" (which uses the power of suggestion), we can see that Hitchcock did evolve with the times. Whether that's a good or bad thing is for you to decide.

"Frenzy" bears a striking similarity to "The Lodger" from 1927; in both, an innocent man is mistaken for a serial killer, and many of Hitchcock's favorite themes — blurred identities, innocent men on the run — appear in the two films. "Frenzy" features a host of British character actors, including Anna Massey, Billie Whitelaw, Jean Marsh, Bernard Cribbins, and Clive Swift. Hitchcock's signature humor is still present in "Frenzy," most notably with the terrible cooking that the detective must endure at the hands of his aspiring cordon bleu wife (also a running joke in the '70s sitcom "Butterflies"). "Frenzy" is definitely worth watching, if only to see how it bookends Hitchcock's career and to appreciate its links with his work in the '20s.

14. Vertigo (1958)

One of Hitchcock's most controversial but highly-lauded works, "Vertigo" is in many ways the zenith of his career and a crystallization of his themes. It frequently tops lists of best movies (not just best Hitchcock movies) and it's easy to understand why — for its use of color, dizzying cinematography, costumes, locations, and performances.

One of the most psychologically complex of Hitchcock's films, "Vertigo" makes an excellent companion piece with the far less-seen (but equally complex) "Marnie." It sees James Stewart very much playing against type, which is one of the reasons this film can be hard to swallow for some people. Scottie's increasingly obsessive and controlling nature towards Judy (Kim Novak) as he molds her from a brunette into the blonde Madeleine is a lot to take, especially when you consider what we now have heard (from Tippi Hedren, among others) about Hitchcock's controlling nature.

It is crucial to watch "Vertigo" if you want an insight into Hitchcock's mindset, but that might not be something everyone is seeking. The main interest is perhaps watching Stewart wrestle with this role and to see so many of Hitch's themes collide atop the bell tower.

13. Blackmail (1929)

"Blackmail" is an extremely important film, being the first British "talkie." It started life as a silent film, then the decision was made to adapt it for sound after filming had begun; both silent and sound versions were released. Watching it now, the first scenes are silent, and then you can hear it transform into a talkie before your very ears (at around the 8 minute mark), which is a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of cinema.

If you haven't seen many pre-code films, you may be surprised to learn that "Blackmail" revolves around a murder in self-defense after an attempted sexual assault. It also features a thrilling chase on the British Museum roof and quite a modern relationship between the central characters — Frank, a policeman, and Alice, the "guilty" party. Frank, Alice, and the blackmailer himself, Tracy, are all morally complex characters, with Frank covering up for his girlfriend and Tracy being mistaken for the murderer. If you haven't seen much '20s cinema, you may find that the characters and plots are more intricate than you expect and, in the case of "Blackmail," that Hitchcock's favorite themes were present from the start.

12. Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

Co-written by Alma Reville, Hitchcock's wife, "Shadow of a Doubt" features one of the most iconic characters in Hitch's oeuvre: Joseph Cotten's Uncle Charlie. His influence has been felt since, most notably in Park Chan-wook and Wentworth Miller's "Stoker" (2013). Charlie in "Shadow of a Doubt" is a brilliant inversion of Hitch's "innocent man on the run" character, as this is very much a guilty man, and we spend the film waiting for everyone else, chiefly his adoring niece (also named Charlie), to catch up.

"Shadow of a Doubt" also makes for a great double-bill with Charles Laughton's "The Night of the Hunter" (1955). With its use of light and shadow, looming silhouettes on stairs, and carefully-composed blocking, the cinematography is stunning. Teresa Wright as young Charlie is also great, as is Hume Cronyn, who also wrote the adaptations of "Rope" and "Under Capricorn" for Hitchcock.

11. To Catch a Thief (1955)

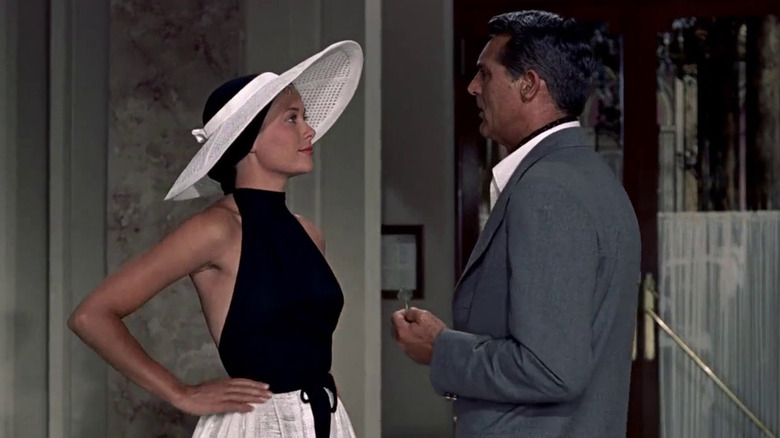

Alfred Hitchcock made three films in quick succession with the favorite of his muses — Grace Kelly — with the third and final being "To Catch a Thief." Kelly was the least icy of Hitchcock's blondes, and her roles involved a warmth, wit, and a bright and breezy nature not afforded to Novak, Hedren, or Leigh.

"To Catch a Thief" has everything you could possibly want from a '50s film — two beautiful people wearing beautiful costumes in a beautiful setting ... and a masquerade ball. Without the moral and psychological complexity of much of Hitchcock's work, "To Catch a Thief" may be seen as minor or non-essential to some. If Cary Grant as a literal cat burglar and Grace Kelly in iconic Edith Head gowns swanning around the French Riviera is something you can turn down, you're a stronger person than I.

Although the cinematography may not be as striking as in some of Hitchcock's other films, the use of green light in the hotel room and rooftops scenes is gorgeous. Ultimately, it's the playful banter between Kelly and Grant that is the real selling point here; this is easily Hitch's most sumptuous and glamorous film.

10. Rope (1948)

One of Hitchcock's most satisfying works, "Rope" is a single-location film that uses a real-time "one-shot" gimmick to brilliant theatrical effect. An unusual early color film from the director, who made his main shift to color in 1954 (with notable exceptions, such as "Psycho," of course), "Rope" was experimental and arduous for the cast and crew to make, even by the standards of other Hitchcock films. The central trio of John Dall, Farley Granger, and James Stewart dance around one another with precisely choreographed dialogue and movement, with the long scenes being carefully rehearsed and blocked.

"Rope," like "Rear Window," is known for the intricate set that can be viewed through the large apartment window. The one in "Rope" is a cyclorama that has real smoke, lights, changing clouds, and a gradual sunset. Treating murder as a game or thought experiment is a perfectly Hitchcockian idea (although "Rope" is based on a play by Patrick Hamilton) and having Stewart play a teacher who espouses Nietzsche is an interesting twist on the "gee shucks" persona we mostly know him for (particularly as someone who railed against Aryan rhetoric in 1940's "The Mortal Storm"). "Rope" is not a film that works for everybody, but it's a streamlined, compact version of Hitchcock that is essential viewing within his body of work.

9. The 39 Steps (1935)

"The 39 Steps" features many classic Hitchcock elements: it has a "MacGuffin" that sparks the plot, a train journey, an innocent man on the run, and a romantic subplot that contains rom-com tropes that are still in use today. Robert Donat plays the everyman who becomes unwillingly embroiled with spies, espionage, and murder, and who spends much of the film one step ahead of the law, desperate to clear his name.

Unlike the similarly-plotted "North by Northwest", where the most famous sequences are on board an Amtrak train, in a dusty midwestern cornfield, and at the famous US landmark Mount Rushmore, "The 39 Steps" has the Flying Scotsman train, the Forth Bridge, the Scottish highlands, and a London music hall as settings. While Madeleine Carroll's Pamela isn't the strongest of Hitchcock's blondes by any stretch, she does get to have a classic "oh no we have to pretend we're married to stay at the inn and there's only one bed" scene. And the Mr. Memory pay-off at the end is one of Hitch's most satisfying endings.

8. Psycho (1960)

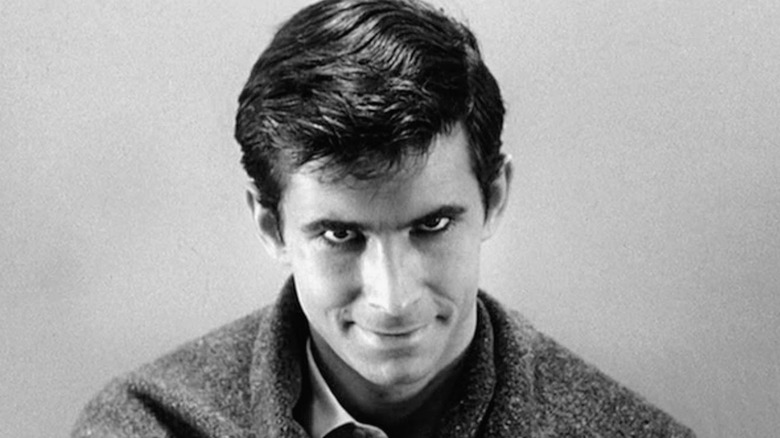

Very much a film of two halves, "Psycho" is Hitchcock's most iconic film, and surely his most widely-seen. Its influence on the horror genre cannot be overstated, but it's actually far more complex than it perhaps first appears. Janet Leigh's Marion Crane is one of Hitchcock's morally sophisticated protagonists. She's set up from the start as a thief who is having an affair, but we are very much aligned with her — and, dare I say, rooting for her — from the start. At the halfway point, after she has checked into a motel with a slightly weird manager — Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) — one of the most shocking movie moments of all time arrives: the infamous shower scene, in which the protagonist is murdered.

There is still half of the film left at this point, and this, being arguably the strongest half, is a work of genius by Hitchcock. The fact that Anthony Perkins didn't win an Oscar for his portrayal of one of the greatest villains of all time is a travesty. There is nothing simple or straightforward about Norman — we frequently feel sympathy for him before that incredible twist ending. Perkins' use of his eyes alone will be studied by acting students for decades to come. It's impossible to say anything about "Psycho" that hasn't already been said. It truly is one of the most important films of all time.

7. The Lodger (1927)

"The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog" is an early film that establishes many Hitchcock tropes. This was the first of two films from 1927 that starred Ivor Novello (better known as a composer than actor), who gets a fantastically dramatic entrance that makes great use of his eyes.

Given what we now know about Hitchcock, the plot of "The Lodger" seems almost unbelievable in hindsight. A serial killer known as the Avenger (yes, really) in London is targeting blonde women, leading to scenes where actresses and models are seen donning dark wigs before going home for the evening, for fear that they will be the next victim. Ivor Novello takes up lodging in a house where Daisy (June Bunting) lives. The Lodger and Daisy start a romance, and he comes under suspicion for the murders, with Hitchcock presenting a lot of red herrings to the other characters and the audience that he is, in fact, the killer. The film climaxes with the Lodger being pursued by a lynch mob, but his innocence is eventually revealed.

Novello gives a good performance in both this and his other Hitchcock film, the very different "Downhill," aided by his strong, straight nose and large, dark eyes. The cinematography is also impressive, with the most iconic shot being a crucifix-shaped shadow falling across Novello's face. An essential work, particularly when coupled with "Frenzy," to get a full picture of Hitchcock from start to finish.

6. Rear Window (1954)

In "Rear Window" James Stewart and Grace Kelly deliver some of their best performances, all contained mostly within the confines of one apartment — and, in Stewart's case, while stuck in a wheelchair. From the masterfully complex set to the performances of the actors giving the tiny (and mostly silent) cameos as the neighbors that Stewart's Jeff spies on, we feel like we're being given a window into very real lives, just as Jeff is.

The crafting of the mystery, including the unbearably tense scene in which Kelly's Lisa enters the apartment of the man they suspect of murdering his wife, is impeccable. Thelma Ritter gives a brilliantly refreshing performance as Jeff's nurse Stella. Once again, Kelly's Edith Head gowns have to be mentioned as a highlight; in contrast to their appearance in "To Catch a Thief," where they fit in perfectly with the Monte Carlo setting, here they are incongruously glamorous in Jeff's small Greenwich Village apartment, making it seem like Lisa belongs to a very different world. Everyone who has seen "Rear Window" shouts through the screen at Jeff that he doesn't deserve or appreciate Lisa, but he just about manages to redeem himself by the end.

"The Rear Window" is another film in which the director's theme (in this case voyeurism) could not be louder or clearer, but "on the nose" is not necessarily a bad thing when it comes to Hitchcock — he's one of the first, and often one of the best, to explore these ideas on film, and always does so with a meticulous eye.

5. The Lady Vanishes (1938)

"The Lady Vanishes" fits into the same comforting space as "Blithe Spirit" (1945) and the various incarnations of Miss Marple: that of competent older ladies (and in this case, a younger one) who are underestimated but ultimately prove their brilliance. There's definitely a dash of "Murder on the Orient Express" thrown in for good measure, too, with an ensemble cast of British eccentrics solving a mystery on a train somewhere in Europe.

With elements of slapstick and farce, while also featuring the Hitchcockian theme of gaslighting, "The Lady Vanishes" is one of Hitch's most fun films. Margaret Lockwood and Michael Redgrave even get to have a romance amongst all of the shenanigans. The MacGuffin being a secret code hidden in a song is very similar to the one from "The 39 Steps," but we won't hold that against Hitchcock. Some may be surprised at how highly I value "The Lady Vanishes," and there is some nostalgia involved, but it has a brilliantly intricate plot and is generally a delight!

4. Notorious (1946)

Featuring a remarkably fresh and modern protagonist in Ingrid Bergman's Alicia and an unbelievably contemporary take on post-World War II events, "Notorious" is a stunning achievement. Bearing in mind that it was released in 1946, "Notorious" deals with German enemies fleeing to South America in the aftermath of the war, and someone who is the daughter of a spy agreeing to marry one of his friends so she can report back to the Americans. It is kind of mind-blowing that this was the plot of a film released so soon after the war ended.

The romantic plot between Alicia and Devlin (Cary Grant) is also extremely complicated — two flawed, damaged people who can't quite get out of their own ways enough to be happy with one another. Grant's character is not smooth or suave or efficient like in "To Catch A Thief," and he doesn't earn our sympathy like in "North by Northwest." In fact, he is downright unlikeable for much of the film, but we are still invested seeing the characters together — it's that obvious that they are desperately in love. Alicia is a promiscuous alcoholic at the start of the film and fights her self-destructive impulses for the remainder; there is so much about "Notorious" that will have you marveling that it was made in the mid-'40s. This is proof that Hitchcock could do romance — while there are still twisted elements here, it is perhaps the most convincing love story that he made.

3. North by Northwest (1959)

"North by Northwest" is a classic Hitchcock espionage thriller that features an innocent man on the run through both famous landmarks (the UN, Mount Rushmore) and more prosaic locales — most memorably, a cornfield in the middle of nowhere. The crop-duster sequence is the only potential rival to the shower scene in "Psycho" for the most iconic moment in all of Hitchcock's work, with Grant's Thornhill in utter disbelief at the lengths these spies will go to in order to get rid of him. Like the shower scene, it's dialogue-free and relies on the facial expressions of Grant, in this case, to really sell the scene. It's also another fantastic costuming moment in a Hitch film, with Grant's impeccable gray suit thoroughly out of place in the dust bowl, completely broken down and disheveled by the end.

"North by Northwest" was one of many successful Hitchcock collaborations with composer Bernard Hermann (also behind the "Psycho" shower scene) and title designer Saul Bass. The Mount Rushmore ending is truly audacious, and while it's strange to think of Hitchcock as an action director, he comes dangerously close to being one in "North by Northwest." Although it is a Sophie's Choice to decide between Hitch-Jimmy and Hitch-Cary, I would ultimately go with Grant, as Hitchcock brings out the best in him.

2. The Birds (1963)

Hitchcock doing classic horror is always going to be a winner, and "The Birds" is no exception. One of the scariest concepts ever, by virtue of the fact that the characters and the audience are never given any explanation as to why it's happening, the greatest strength of "The Birds" is its simplicity. Tippi Hedren's Melanie Daniels arrives in Bodega Bay in pursuit of a hot man she's just seen (already off to a banger from the start) and birds start randomly attacking her and the wider community.

Not for the first time in Hitch's work, Melanie is a morally flawed woman who brings misfortune to those around her. The object of Melanie's lust, Mitch (Rod Taylor) has an overbearing mother (played by Jessica Tandy), another character type who became a more prominent feature in Hitchcock's later work (said to be sparked by the death of his own mother). Some theories are that the mother somehow conjures the birds to get rid of Melanie, but it's better and more chilling to believe that it's just completely random.

"The Birds" has its own iconic scenes, of course, chief of which is the jungle gym outside the school gradually filling with birds behind an oblivious Melanie. I find birds gathering in any number extremely unnerving to this day.

1. Rebecca (1940)

My number one and number two Hitchcock films are both adaptations of Daphne Du Maurier stories, so you're probably gathering where my tastes lie. Gothic fiction is one of my greatest loves, so combining that with Hitchcock is always going to result in a perfect film — and that is what "Rebecca" is. Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson) should be considered alongside Norman Bates as the iconic villain she truly is. Joan Fontaine is a fantastic second Mrs. de Winter, desperately trying to fit in and do the right thing at Manderley, the grand home her much older husband (Laurence Olivier) brings her to.

Class is a big factor in the plot of "Rebecca" and is a theme that Hitchcock would surely have explored more if he'd continued to work in the UK — the irony being, of course, that "Rebecca" was actually his first Hollywood film. This film also features one of my favorite actors (with a voice like treacle), George Sanders, as Rebecca's lover Jack Favell.

"Rebecca" is proof that not all ghost stories need a ghost. If the living believe enough in a dead person's power, their presence will continue to be felt and affect the lives of everyone in their vicinity. Hitchcock as an adapter is not discussed enough, but many of his films were based on books and plays, even if he always managed to put his own stamp on them. The book is beautifully written, but this is one of the best book adaptations of all time. "Rebecca" is a masterpiece.