The 25 Greatest Femme Fatales In Movie History

The femme fatale is one of the most classic (and best) tropes in cinema. Although they existed in movies made before 1940, the character type was solidified during the noir boom of that decade. Birthed out of the pulpy detective novels of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and James M. Cain, the femme fatale was beautiful, duplicitous, dangerous, and would frequently cause the downfall of some poor dope who became entangled in her web.

The fatale could be fatal in the deadly sense, of course, but also would frequently be the protagonist's fatal flaw, sometimes unwittingly; obsession is certainly a huge factor in the trope. The stereotype could often be portrayed in more nuanced ways than what was on the glacial surface, with layers of vulnerability and tragedy underneath. After a fallow period in the '50s to the '70s, the '80s and '90s brought the femme fatale back with a vengeance. Directors such as Adrian Lyne, Paul Verhoeven, and Brian De Palma ushered in the age of the erotic thriller, which undoubtedly feature some of the best femme fatales.

The defining characteristic of the femme fatale is that she will stop at nothing to get what she wants (usually money and freedom), and will use everything in her power to manipulate others into achieving her ends. While she will sometimes get her own hands bloody, it's far better to find someone else to do the dirty work. Here are the best femme fatales in movie history.

Phyllis Dietrichson - Double Indemnity

Femme fatales generally fall into two categories as far as looks go. You'll see those with black hair and black outfits (what you would typically expect from the black widow type), or the icy blond who wears white (see: "Body Heat" and "Basic Instinct"). Perhaps the prototype of the latter category is Barbara Stanwyck as Phyllis Dietrichson. Director Billy Wilder and co-screenwriter Raymond Chandler adapting James M. Cain's novel make a good case for the best film noir of all time. Stanwyck was coming off of the screwball rom-coms "The Lady Eve" and "Ball of Fire" (both released in 1941) before delivering one of the best femme fatale performances in history.

Fred MacMurray plays the patsy, pretty much defining this character type, who becomes embroiled in Phyllis' devious scheme to kill her husband for the insurance money. Stanwyck makes an all-time-great entrance, completely upending Walter Neff's life from the get-go. One of the biggest pleasures of watching a femme fatale is knowing that the male protagonist is doomed the moment he meets her; there is no escape from her clutches. Stanwyck also brings her customary wry humor to the role, meeting Neff in a grocery store wearing conspicuous sunglasses, and Wilder makes great use of the huge height difference between them. All femme fatales since have been in the shadow of Phyllis Dietrichson. (Fiona Underhill)

Ellen Berent Harland - Leave Her to Heaven

In terms of the brunette leading ladies of the '40s, the two most beautiful were probably Ava Gardner and Gene Tierney, and both effectively weaponized their beauty as femme fatales. Having starred in "Laura" the year before, Tierney returned to the psychological thriller with "Leave Her to Heaven," an unusual noir for several reasons, not least that it's in technicolor. Tierney's Ellen is also a rare femme fatale in that her motivations are not financial. Instead, it is obsession and possessiveness that she transfers from her father to her husband. She is pathologically jealous of anyone who competes for his attention; she must consume him whole.

In this, "Leave Her to Heaven" is at the Gothic melodrama end of the noir spectrum, but Ellen's magnificent fashion and her cold-blooded, ruthless side place her firmly in the fatale camp. Ellen has what would be considered traditional male qualities in that time period: ambition, drive, competitiveness, making the first move with the person she desires and even being the one to propose. She is also disgusted when she falls pregnant; she wants no part of the traditional nuclear family and doesn't want to share her man with anyone, including her own child. Ellen is another murderous femme fatale that also earns our sympathy because she refuses to conform to the pressures and expectations of women at the time, making for a fantastic character. (Fiona Underhill)

Veda Pierce - Mildred Pierce

The two youngest femme fatales on this list — the teenage Veda and Kathryn in "Cruel Intentions" — are arguably the evilest. Veda is an unusual femme fatale, as her prime victim isn't a man, but her own mother. Poor Mildred (Joan Crawford) sacrifices her own happiness and centers her life around aiding her daughter's ruthless ambitions, which is to social climb her way to a lavish lifestyle. All the men in the movie, including Bert, Monte, and Wally, are of varying degrees of being useless and selfish, but none are as wicked as Veda.

Veda lies about being pregnant, blackmails, brings shame to her family by becoming a scantily-clad entertainer, and even has an affair with her mother's husband. She uses the fact that her mother will do anything for her to her advantage, including coercing her mother into covering up a murder and pinning it on Wally. Even when Veda is eventually caught, Mildred still tries to apologize to her, and is rebuffed; the ultimate tragic ending for Mildred. "Mildred Pierce" is unusual in that the protagonist, who becomes the patsy of the femme fatale, is a woman. While it's largely a domestic melodrama, the framing device (Mildred is interrogated by the police, with the story told in flashbacks) and the murder plot, especially the way it's shot with the dramatic use of light and shadows, places it firmly within the noir genre. (Fiona Underhill)

Kitty Collins - The Killers

Many of the best noirs are adaptations of equally brilliant books, and 1946's "The Killers" is no exception. The movie is based on a story by Ernest Hemingway, and was one of the few adaptations that he didn't despise. An important element of a great femme fatale is a great name, and Kitty Collins could be a Bond girl name — it's that good. Like all the best noirs, the minute the protagonist (Burt Lancaster, in his first film role, playing The Swede) meets the femme fatale, he is doomed. He will do anything for her, including going to prison for a crime he didn't commit.

Ava Gardner has an iconic look as Kitty that was used in some of the hottest publicity stills of all time: a black sleeveless dress with a swathe of fabric that crosses her neck like a hangman's noose. Kitty is the ultimate self-centered femme fatale, who only cares about saving her own skin, and doesn't mind who gets sacrificed along the way. The Swede is the tragic hero; he can see the whole path laid before him, he knows who Kitty is, but is powerless to stop the inevitable events from unfolding. He resignedly accepts his own death, while Kitty desperately refuses to accept that her goose is cooked in the movie's perfect closing minutes. Gardner's beauty, combined with a fantastically-written character, makes for one of the best femme fatales in cinema. (Fiona Underhill)

Cora Smith - The Postman Always Rings Twice

A femme fatale needs to make a great entrance, often one that seals the fate of the protagonist. Once Lana Turner emerges through a doorway dressed from head-to-toe in white, in an outfit that shows plenty of leg, it's curtains for poor John Garfield. She continues to wear white throughout the film (apart from a couple of rare uses of black at key moments), which is a veneer of purity that belies her rotten core. Like many femme fatales, Turner's Cora is trapped in a life she doesn't want and desperate for a way out. She entices Garfield's Frank into a classic "kill the husband" murder plot, but the story goes through many unpredictable twists and turns.

The pallor of inevitability hangs over the couple and no matter what they do, things keep going awry, sealing their fate. Turner is great at communicating barely-concealed panic behind an icy exterior. One of the highlights is the interrogation and confession scene, with the two lawyers rising up as the best characters in the movie. Turner became so iconic that she's even referenced in 1997's "LA Confidential" when Ed Exley utters the immortal line, "A hooker cut to look like Lana Turner is still a hooker." Along with Ava Gardner, Turner's Cora helped define the look of the femme fatale and her white outfits would become the blueprint when the character trope returned in the '80s and '90s. (Fiona Underhill)

Kathie - Out of the Past

While Jane Greer isn't as well-known as some of the other stars who played iconic femme fatales during their 1940s heyday, her beauty still makes her a memorable one. Plus, it helps that she was in one of the all-time great noirs. Robert Mitchum plays the perfect protagonist, who has tried to escape a life of crime, but it comes knocking at his door. "Out of the Past" contains the homespun girl Mitchum is trying to build a new life with, contrasted with Greer's beautifully dangerous Kathie. It's funny that the name Mitchum chooses in his new small-town life is Jeff Bailey, as he has a lot in common with George Bailey of "It's a Wonderful Life."

Kathie runs through the entire femme fatale playbook: seduction, blackmail, murder, double-crossing, and framing her patsy. Jeff tries to escape her clutches but keeps getting drawn back to her. Greer's performance is so good that despite all of the despicable acts that Kathie commits, we can never be completely sure that she doesn't love Jeff or genuinely care about him. "Out of the Past" has a wonderful framing device and another all-time-great ending, employing an unusual noir character — the deaf-mute Kid. This noir embodies the post-war concerns of a glamorous criminal life posing a threat to small-town America. But it isn't money that is the pull for Jeff, it's Kathie, embodied by a magnetic Jane Greer. (Fiona Underhill)

Jane Palmer - Too Late for Tears

A bag full of cash mysteriously lands in the car of Jane and her husband, and Jane spends the rest of the movie doing anything to hold onto it. The simplest noir plots are often the best, and "Too Late for Tears" has a classic one. Lizabeth Scott's Jane is bored of her small, humdrum life and is desperate for more, so when the cash lands in her lap, she wastes no time in buying furs and other luxuries. Her husband is much more suspicious and cautious about where the money has come from, so he has to go.

The man who is the source of the money, Danny (Dan Duryea), quickly tracks them down and Jane just as quickly enters into cahoots with him. Scott's husky voice is perfect for a femme fatale who spends an entire movie lying and manipulating. Her poor sister-in-law Kathy becomes suspicious about where her brother is, and Jane must keep her various stories straight — with the police, with Danny, and with Don Blake, a mysterious stranger who also comes looking for her husband. Like all the best noirs, "Too Late for Tears" has a stupendously melodramatic ending, with Jane getting her just desserts in spectacular fashion. Noirs where the femme fatale is the main character are few and far between, and this is a great example of one. (Fiona Underhill)

Madeleine Elster/Judy Barton - Vertigo

A list of femme fatales wouldn't be complete without Alfred Hitchcock, and his twisted version of the trope. Hitchcock's blonds were frequently cold and calculating, but also subject to the foibles of the male characters. Maybe Hitchcock's most psychologically complex film is 1958's "Vertigo," in which James Stewart's Scottie becomes obsessed first with the mysterious Madeleine, then with Judy (both played by Kim Novak), who he models in her image. While Judy has some classic traits of the femme fatale (deception and duplicity for monetary gain), she is also a tragic figure, wracked by guilt. Whether she's good or evil is greatly complicated by Scottie's actions, as he doesn't view Judy as a human being, but as a cipher for the ghosts of Madeleine and her ancestor Carlotta. Possession from essentially being haunted and also by Scottie's ownership is at the center of "Vertigo."

As with all Hitchcock tales, there's nothing simple about Novak's femme fatale, but she's perhaps the ultimate expression of the trope. Scottie molds Judy, dying her hair and putting her in the right suits, into the perfectly constructed Hitchcock blond. She doesn't exist unless she is being perceived by Scottie, by Hitchcock, and by the audience. "Vertigo" is a reminder that the femme fatale is one of the most cinematic tropes as she is made to be immortalized and worshipped on the silver screen. (Fiona Underhill)

Mrs. Grayle - Farewell, My Lovely

After appearing in some of the best noirs of the 1940s and 1950s, Robert Mitchum returned to the genre decades later by playing the famous noir detective, Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, in 1975's "Farewell, My Lovely" and in 1978's "The Big Sleep." Thank goodness that neo-noirs exist, because some women were born to play femme fatales, and Charlotte Rampling is absolutely one of them. When Marlowe visits the Grayle mansion in the course of his missing-person investigation to find a woman named Velma, he meets Judge Grayle (played by crime novelist Jim Thompson) and his much younger, beautiful wife, who immediately sets about flirting the pants off him.

While she initially appears to be a fairly incidental side character, it is gradually revealed that Mrs. Grayle is pulling the strings behind the whole operation and is actually the woman that Marlowe has been seeking. She has been killing off anyone who suspects her true identity. Rampling appears in two main ensembles — a red dress with a green jade necklace in her initial meeting with Marlowe, then a beautiful white silk dress with pearls during the big reveal scene (accessorized with a revolver, of course). Her brunette hair and piercing eyes make for a dangerously beautiful femme fatale. These two '70s Marlowe movies are an interesting variation on the noir before the genre was fully embraced once more in the '80s. (Fiona Underhill)

Matty Walker - Body Heat

A direct descendent of both Barbara Stanwyck's Phyllis Dietrichson and Lana Turner's Cora Smith (including being clad in white silk for most of the movie), Kathleen Turner's Matty Walker is easily one of the best femme fatales of all time. "Body Heat" helped usher in the erotic thriller boom of the '80s and early '90s. Her initial meeting with the patsy Ned (William Hurt) is full of flirty banter, with remarks like, "You're not too smart, are you? I like that in a man." The heat of the title has different meanings in this movie. It's set during a Florida heat wave, everyone is constantly sweating, and then the steamy scenes only increase the temperature.

The conniving Matty dupes Ned into killing her husband, then does a disappearing act for almost half of the movie. She's such "big-time, major league trouble" that she leaves Ned to clear up the mess she's got him into. While '40s noirs usually had to show the femme fatale getting her comeuppance, the '80s were free to show her getting away with murder. Kathleen Turner would of course go on to play the misunderstood Jessica Rabbit in "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" (who looks like a femme fatale, but has a heart of gold), proving that one of her greatest assets is her husky voice. Turner is an all-time great screen siren and Matty Walker is a character for the ages. (Fiona Underhill)

Rachael - Blade Runner

Before Jessica Rabbit, there was Rachael, who is "not bad, just made that way." In maybe the best neo-noir of all time, Sean Young's Rachael is given the ultimate 1940s femme fatale look: black hair, almost-black eyes, red lips, white fur coat and shrouded in cigarette smoke. Like many Bond girls, she works for the villain (in this case, the evil Tyrell Corporation), and she is a replicant. Therefore, she is supposed to be the enemy and target of the protagonist, the hard-boiled Detective Deckard.

However, Rachael is revealed to be the ultimate victim, who has had no control over her life since "birth." She is Tyrell's experiment, a replicant who believes she's human and who has had false memories implanted in her brain. Not that she needs redeeming, but she also saves Deckard's life and he cannot help but be drawn to something he's spent his life despising. Young's performance is extraordinary, a preternatural blank slate on the surface, but one who elicits huge sympathy from the audience as one of the most tragic film characters in science fiction. 2017's "Blade Runner 2049" only deepens her sad story, as she dies giving birth to Deckard's child, something not thought possible in replicants. Many femme fatales are revealed to be more vulnerable once you break through their glossy exteriors, but none more so than Rachael. (Fiona Underhill)

Miriam - The Hunger

Catherine Deneuve plays the stunningly beautiful Miriam, a rich New Yorker, and has the classic femme fatale look: black or white suits, red lips, black hats, sunglasses, and gloves, all enveloped in curls of cigarette smoke. But there is more to this woman than just the usual seduction for money — she is a vampire. Miriam turns people into long-lasting companions, and they, including John (David Bowie), usually willingly comply, believing they will achieve eternal youth. There's a twist, though, in that they will eventually rapidly age and deteriorate, but be unable to die.

Sarah (Susan Sarandon) becomes ensnared in Miriam's web, and like many of the best neo-noirs, an obsessive but dangerous attraction between two women is really at the heart of this film. Vampire movies are obviously the best genre for featuring all-consuming love because it can last centuries. Vampires are both blessed and cursed with immortality, and Miriam's eventual downfall comes when she meets the same fate as John. It is very easy to understand why anyone (even those with their own sexual potencies, such as Bowie and Sarandon) would become undone when faced with a woman such as Deneuve's Miriam. She renders mere mortals helpless before her, and they would sacrifice anything to be with her. Tony Scott's "The Hunger" is a brilliant erotic thriller, with a vampiric twist centered around three of the sexiest central stars of all time. (Fiona Underhill)

Catharine - Black Widow

The first time we see Theresa Russell's titular black widow, she couldn't fulfill expectations anymore with a black fur coat, and huge sunglasses set against a bob of blond hair. As the film progresses, she gradually looks and becomes more human. Catharine adopts many identities throughout the movie, making herself "appealing" to different types of men, who all have only one thing in common: wealth. But the most interesting relationship in Bob Rafelson's "Black Widow" isn't with any of the men that Catharine weds-then-sheds. It's with Debra Winger's Alex, who starts to have a "Killing Eve" type of obsession over the woman she's hunting, determined to prove that a series of mysterious deaths in different states are connected. Alex ends up befriending Catharine in Hawaii (both of them going by different names, of course), and they even share the same man for a while.

Catharine remains enigmatic throughout the film. We're never clear why she continues killing when she has more money than she could possibly need. While she seems bored with men and views them as obstacles to be overcome, it's clear that Alex excites her and presents a challenge. Manipulating Alex is the only time Catharine is engaged and motivated; she wants to win this particular game of cat-and-mouse. "Black Widow" is a rare example of a femme fatale with a woman as a foil, and therefore should be more widely seen. (Fiona Underhill)

Alex Forrest - Fatal Attraction

Glenn Close's Alex is a descendent of Gene Tierney's Ellen in "Leave Her to Heaven," in that her motives are an obsessive need to wholly possess the man of her desires, rather than attain money, power, or freedom. Unfortunately, the phrase "bunny boiler" has now become synonymous with any woman acting in a way that a man might find distasteful, and it's not the most progressive depiction of someone who clearly has mental health issues. "Fatal Attraction" is very much of its time, and along with "Basic Instinct" helped define the era. They were both hugely successful, with each grossing over $300 million worldwide. "Fatal Attraction" was the second highest-grossing film of 1987, something that is hard to imagine happening today.

Glenn Close delivers an extraordinary performance as Alex, and it makes a great contrast to the femme fatale she played the following year as the Marquise de Merteuil in "Dangerous Liaisons." Michael Douglas is also perfectly cast as Alex's "victim" Dan, and Anne Archer is just as important as his wife, Beth. "Fatal Attraction" has gone on to have a cultural impact beyond the film itself and taken on a life of its own. It's a great '80s psychological thriller, with a cathartic ending that preserves the American nuclear family. It is fun to watch a femme fatale with no motivation beyond an all-consuming love, as it makes a change from all the money-grabbers. (Fiona Underhill)

If you or someone you know is struggling with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Selina Kyle - Batman Returns

Michelle Pfeiffer and Tim Burton's take on Catwoman has rightly become iconic, not least because of the look of the character, and her apartment. While Catwoman's catsuit and whip are famous, it's Pfeiffer's looks while in Selina Kyle mode that leave even more of a lasting impression. Her wild blond curls and dark eye makeup make her look suitably unhinged (but wildly sexy), once she has had a hit on the head that frees her from being a mousy spinster secretary. But nothing compares to her entrance at the party near the end of "Batman Returns," as a full-blown femme fatale. She's absolutely show-stopping with curls swept up but tumbling down her face, a bold red lip, and a sparkly backless little black dress.

In addition to looking perfect, Pfeiffer's performance rides the gamut from confidently flirting with Bruce Wayne, or staring vengeful daggers at her boss, Max (Christopher Walken), and plotting his demise, even to tearful desperation. She is scared and confused about the fact that her own mind has become a stranger to her. Her ending in which she says, "Bruce, I'd love to live with you in your castle forever ... I just couldn't live with myself," is actually pretty heartbreaking, given that this is a comic book villain. Pfeiffer's Catwoman is a legendary movie villain in the flavor of femme fatale, with some of the most striking looks of all time. (Fiona Underhill)

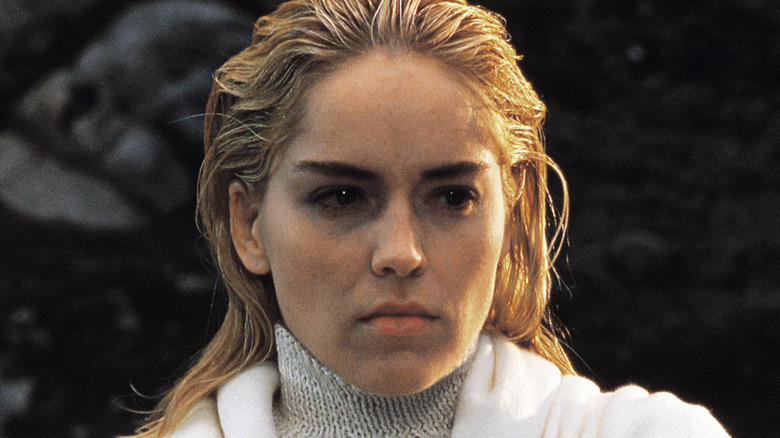

Catherine Tramell - Basic Instinct

With its San Francisco setting, emphasis on voyeurism, and its femme fatale with swept-back blond hair and dark eyebrows, there is no doubting the influence of "Vertigo" on Paul Verhoeven's most successful erotic thriller. Sharon Stone's Catherine is a crime novelist, who commands such power in "Basic Instinct" it's as if she's writing the very script we're watching unfold. Catherine presents a threat on many fronts, not least her command of her sexuality and the fact that she doesn't need a man to be fulfilled.

Michael Douglas' booze-soaked cop is a classic noir protagonist, with the '80s element of cocaine added into the mix. He is pushed and pulled around by three femme fatales, including Catherine's lover Roxy (Leilani Seralle) and former lover Beth (Jeanne Tripplehorn), whose identities blur and merge at times. Elements of "Basic Instinct" have become as iconic as "Fatal Attraction," with the ice pick being as well-known as the boiled bunny. It's impossible to overstate the importance of Stone's look, surely influenced by Katherine Turner's look in "Body Heat" over a decade before. Verhoeven took the ingredients of noir, including light filtered through blinds and rain-soaked windows, and has enormous fun splashing around in the tropes. Stone's Catherine is an all-time great femme fatale who has become the stuff of legend, deservedly so. (Fiona Underhill)

If you or anyone you know is struggling with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Suzanne Stone - To Die For

Loosely based on the true story of Pamela Smart, Nicole Kidman's Suzanne is an ambitious and ruthless femme fatale, who kills to achieve her 15 minutes of fame. After all, "You're not anybody in America unless you're on TV." With "The Real World" premiering in 1992, "To Die For" captured a moment in time when reality television was on the rise, and also when such events as the O.J. Simpson trial were must-see television. Matt Dillon plays the victim, Suzanne's husband Larry, and Joaquin Phoenix plays the teenage patsy who Suzanne seduces in order to get him to commit murder. Illeana Douglas delivers a delectable performance which she relishes in the small role of Larry's sister, Janice.

Kidman has furrowed a brilliant career peeling off the façade of the American dream in roles such as "The Stepford Wives" and "Stoker." Suzanne is one of her best-ever performances, as Suzanne herself is delivering a performance throughout the film. Each decade has provided its own brilliant twists on the femme fatale that gives them motivations that make sense for the time they are depicting. In the '40s, it was often about escaping a husband, but in the '80s and beyond, they're often ambitious career women (e.g. Sigourney Weaver in "Working Girl"). Kidman's Suzanne is a deliciously devilish example of the femme fatale as a professional woman who will do anything to climb the corporate ladder.

Kathryn Merteuil - Cruel Intentions

It should come as no surprise that one of the best femme fatales comes from an 18th-century French novel when it's one as rich as "Les Liaisons Dangereuses," and already had such a brilliant film adaptation in1988's "Dangerous Liaisons." While '90s movies like "Clueless" and "Ten Things I Hate About You" tend to be hailed as the best modern-day literary adaptations, "Cruel Intentions" can be overlooked; it's just as good, if not better. The Marquise de Merteuil becomes Sarah Michelle Gellar's Kathryn, and it's hard to overstate how shocking this performance was from Buffy Summers, even transforming into a brunette. Transporting the setting to an elite Manhattan prep school is a genius idea, and Kathryn is truly Machiavellian, manipulating everyone around her including ingenues Annette (Reese Witherspoon) and Cecile (Selma Blair), and most especially, her step-brother Sebastian (Ryan Phillippe).

Witnessing Kathryn's downfall is undoubtedly one of the great pleasures here and it leads to an iconic finale set to The Verve's "Bittersweet Symphony." She has lied, blackmailed, and destroyed lives, all just as a distraction from being bored and while maintaining the veil of hypocrisy throughout, exemplified by her cocaine-filled crucifix. Her comeuppance is at the hands of Annette, Cecile, and Sebastian (from beyond the grave) and could not be any sweeter. A brilliant performance from Gellar as one of the evilest femme fatales ever.

Rita - Mulholland Drive

Like "Black Widow," David Lynch's masterpiece pits two women as enemies, lovers, and more, rather than having the traditional male protagonist/patsy. The naive blond Betty (Naomi Watts) arrives in Tinseltown with stars in her eyes, only to collide with Laura Harring's beautiful, dark-haired Rita. Her identity (borrowed from Rita Hayworth) and motivations are opaque. Does she really have amnesia? Betty projects a lot onto the seemingly blank slate that is Rita, and she becomes the person that Betty wants to be, as well as love.

The final quarter of "Mulholland Drive" brings things into sharper relief, while also muddying the waters further. It is only really when Harring plays Camilla that she fulfills the femme fatale archetype, as she seems to enjoy making Diane (Watts again) squirm. The fact that Harring is clearly styled, with her black hair and red clothing, to be the femme fatale (in contrast to the innocent blond Betty) is interesting in itself, as for most of the film, she is anything but. Attempting to clearly define anything that happens in a Lynch project is a futile exercise, but he clearly relished using noir conventions as his playground. A film about the duplicity of Hollywood, the blurring of identities, and the dangers of pursuing dreams and fantasies — or is it? It doesn't really matter, just let its stunning imagery wash over you.

Laure - Femme Fatale

Brian De Palma is one of the great neo-noir directors, with "Dressed to Kill" and "Body Double" as examples. In the 2000s, he revisited the genre with "Femme Fatale" and "The Black Dahlia." It's impossible to have a list of the best femme fatales and not include this homage to the archetype. The opening sequence, set at the Cannes Film Festival, is phenomenal and pulls off a very Bond-like diamond heist, but with Rebecca Romjin seducing a female victim. A common feature of the femme fatale is assuming multiple identities, and Romjin is no exception here. It probably didn't help its critical or box office reception that it has several similarities to Lynch's "Mulholland Drive," released just the year before, including the "was it all a dream?" final act.

Like many erotic thrillers, "Femme Fatale" has had a critical reappraisal and is now considered a cult classic. Roger Ebert, as usual, was on the right side of history at the time of release. A film called "Femme Fatale" of course pays tribute to those that have gone before, such as Romjin's Laure watching "Double Indemnity" and the fact that she is very much an Alfred Hitchcock icy blond. Antonio Banderas makes a fantastic patsy, and the various twists and turns take the audience on a wild ride. De Palma is one of the best to ever do it, and this is a fantastic example of the genre.

Nina Romina - Nightcrawler

While Rene Russo's TV station news director Nina is up against an arguably even more evil character (Lou Bloom), Nina is also self-serving and morally corrupt. In "Nightcrawler," (directed by Russo's husband, Dan Gilroy) power, status, and who's in possession of the upper hand frequently shifts between Lou and Nina. Initially, Lou is desperate to impress her with his footage of car accidents and crimes. Nina emphasizes that more graphic content is better, and if it's in affluent white neighborhoods, it's even more valuable.

Once Lou's footage is in-demand, he uses this as leverage to get Nina to sleep with him. Nina does ultimately use her sexuality to get what she wants — the ultimate femme fatale power move. As Lou's footage becomes increasingly ethically dicey, and he commits crimes in order to capture it, Nina's admiration of him only grows. She has no qualms about withholding evidence from the police, manipulating her audience by cutting the footage, and withholding certain facts that aren't ratings-friendly. Nina is a very modern femme fatale, dealing in the TV news version of clickbait, a valuable commodity nowadays. Just as the fatales of 1940s noirs were in pursuit of money and power, Nina wants to be at the top of her professional game and doesn't care who gets hurt in the process. "Nightcrawler" is one of the best L.A. neo-noirs, and Russo's Nina demonstrates how the fatale trope has evolved over time.

Anna - Criss Cross

Robert Siodmak made Burt Lancaster a star in his 1946 noir classic "The Killers," so the filmmaker evidently had no compunction about serving him up as a steaming hot lunch to Yvonne De Carlo three years later in his noir masterpiece "Criss Cross." De Carlo's casting was a bit of studio system luck, as Siodmak and producer Mark Hellinger's plan to reunite Lancaster with his "The Killers" co-star Ava Gardner got derailed when MGM refused to loan their ultra-glamorous superstar to Universal International. So De Carlo, a big-screen stunner known as the "Queen of Technicolor," slipped into the part, and slid a dagger into Lancaster's crazy-in-love schemer Steve Thompson overheated heart.

Unlike many of the femme fatales on this list, Anna is not a willing maneater. Sure, she's manipulative, but mostly out of self-defense. Steve and his lethal competition for Anna's affections, gangster Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea at his murderously sleazy best), mean to possess her. Anna is a spitfire who can dance up a storm and banter with bite, but she keeps circling back to the pathetically obsessed Steve (her ex-husband) and the viciously abusive Slim. Anna just wants out of Los Angeles and to be rid of these men, so she goes along with Steve's hastily hatched (though meticulously planned) armored car heist. It all goes down twisted, but Anna – who, via her heartbreaking, eve-of-the-crime scene with Steve (screenwriter Daniel Fuchs employs a twisty flashback structure), seemed willing to give it one last go with Steve – winds up with the money. For once, she gets to work a double cross, and, man, has she ever earned it. But in a movie this nasty, you know it's all going to end in bullets and tears.

Annie Laurie Starr - Gun Crazy

17 years before Faye Dunaway set the screen ablaze as tommy-gun toting outlaw Bonnie Parker, Peggy Cummins set the bad-girl-on-the-lam gold standard as Annie Laurie Starr in Joseph H. Lewis' formally audacious "Gun Crazy." This film runs red hot for it the entirety of its fleetly paced 87 minutes, and the heat emanates almost exclusively from Cummins. In most tellings of this sordid tale, Annie's husband Bart (John Dall), a reform school misfit who's got a distressing predilection for firearms, would be the unhinged engine of the narrative. But while Bart's a deadeye with a pistol, he's sworn to never use his skill to kill a living creature.

Annie, also a crack shot, has no such misgivings. When the couple, having gone broke, embark on an armed robbery spree, it doesn't take long for Annie to flaunt her homicidal tendencies. But while we know a somber outcome is inevitable, Cummins live-wire performance keeps us captive to the criminal moment and, frankly, turned on. No one's ever been this scintillatingly good at being so unrepentantly bad. Even better, what could've been a one-note piece of grandstanding villainy takes on a tragic dimension when Annie confesses that she kills out of fear and confusion. Given the vile treatment she received from her leering carnival boss early in the film, we know it's men who made her this way. We can't justify her actions, but we also can't blame her for walking through this wicked world armed and angry.

Bridget Gregory - The Last Seduction

Linda Fiorentino exploded out of nowhere in 1985 with a trio of indelible performances in "Vision Quest," "Gotcha" and "After Hours." She devoured her boyish co-stars (Matthew Modine, Anthony Edwards and Griffin Dunne) with a casual rapaciousness that suggested she just might be the second coming of Rita Hayworth. But when producer Mark Canton told her, "You have a great ***, but I think your jeans need to be tighter," Fiorentino nearly walked away from acting altogether. When she returned three years later, she struggled to find roles worthy of her incendiary screen presence. Hollywood was letting her down.

So Fiorentino ditched the studios and hooked up with neo-noir craftsman John Dahl, who handed her the keys to a devilish dame named Bridget Gregory. She's bad as can be, but in a world run by cruel and/or stupid men, you'd have to be a prig to not get off on her invigoratingly unpredictable crime spree that supercharges all 110 minutes of "The Last Seduction." Whether she's making a fool out of her abusive husband Clay (Bill Pullman) or toying with dopey insurance salesman Mike (Peter Berg), Bridget seems to be having the time of her life making a joyously illicit killing. Fiorentino's stiletto-sharp, stingingly sensual performance was worthy of a Best Actress nomination (and, I'd argue, a no-brainer win in a weak year carried by Jessica Lange), but the film got inexplicably shunted to cable. She did win Best Actress at the Independent Spirit Awards, at which point Hollywood rediscovered her and went right back to squandering her immense talent. Bridget Gregory was too much woman for these scared hacks.