What The Black Phone Does Better Than Actual True Crime Stories

Note: This article contains spoilers for "The Black Phone."

The fascination with the evilest parts of humanity has always existed, in one way or another. If there is any subgenre of entertainment that has seen a significant increase in popularity over the past few years, it's true crime. When you search "true crime" on Google, you'll be presented with websites dedicated to real-life mysteries and even the Netflix genre page gathering all their true-crime content together. Podcasts, YouTube channels, and forums discussing the horrors of the real world have been popping up faster than you can say "Zodiac." According to The Ringer, the number of true-crime docu-series grew by 63% between January 2018 and March 2021, an unsurprising but still startling statistic.

So, what exactly does this have to do with "The Black Phone," a completely fictional horror film about a serial killer and his victims? It actually matters a ton. While the Grabber might not actually exist, he is reminiscent of other real-life killers that have reached infamy with their crimes. In fact, Joe Hill, the author of the short story the movie is based on, recently told /Film that his original inspiration for the character was John Wayne Gacy.

However, despite its advertising focusing on its sinister villain, "The Black Phone" does something that true-crime media often neglects; it focuses on the victims and the tragedy that befell them more than the person who took their lives, just in a unique way.

But first, a bit of history

Despite its mainstream growth in popularity, the idea at the core of the true-crime subgenre dates as far back as the 16th century. According to JSTOR, many authors made a living printing crime pamphlets, books of "roughly six to 24 pages" that recounted the details of specific crimes. These pamphlets, read primarily by the rich and educated, often covered brutal murders with the specific intention to shock and terrify people who dared to look at the graphic recreations. Those who couldn't read would often recant the printed story, with the specific facts likely being changed in the process.

Just as how the fascination with true crime has been around for a long time, so has the desire to solve these mysteries without actually being at the crime scene. The term "armchair detective" has its historical roots in fiction, with Edgar Allen Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle writing characters who attempt to solve crimes just by looking at evidence and creating theories based on them. However, the term rose in popularity starting in 1967 thanks to the fanzine "The Armchair Detective," where readers attempted to close unsolved cases by publishing evidence, theories, and commentary.

It's the first thing you lose

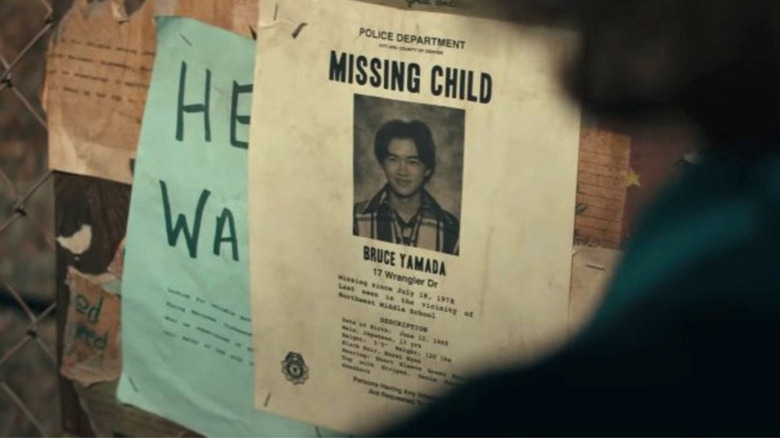

Now, let's apply all of this within the context of "The Black Phone." As seen at the beginning of the film, the Grabber has already developed a reputation for his prolific kidnappings, resulting in a rumor that if you say his name, he'll come after you. Meanwhile, posters showing the details of missing children continue to be put up, ignored by passersby as they believe they're of no use. The film's central protagonists, Finney (Mason Thames) and Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) do take notice, but only because Finney mentions how the mother of one missing child, Bruce (Tristan Pravong), has begun putting up posters again despite the lack of progress.

It is a shame, too, that he has been reduced to a poster attached to a chainlink fence or wall. In a dreamy montage that introduces Gwen's psychic abilities, both she and the audience get to see Bruce live his life, from infancy to reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in school, to the moments right before he gets kidnapped by the Grabber. He was a regular kid who had barely experienced life, whose name will always be tied to the man that took it from him.

Bruce isn't the only kid the Grabber killed. While his other victims do not get lengthy life-spanning montages like him, Gwen and the audience get to see how the other kids lived their lives through her psychic dreams. Even if they aren't long, they're reminders that they still had so much ahead of them.

Unbeknownst to the Grabber, however, they haven't yet completely left this world.

You need to stand up for yourself

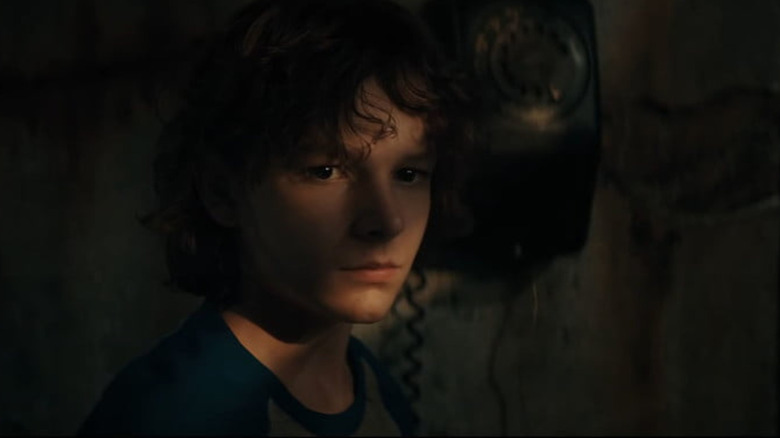

When Finney is abducted and thrown into the same underground cellar where they were killed, the boy discovered that he could communicate with them through the disconnected telephone hanging on the wall. These spirits are lost and unsure of their own identities, but they all have one thing in common; they are angry that they weren't able to survive, no matter their attempts at escape.

And make no mistake, they tried their hardest. Bruce tried digging a hole from the basement's dirt floor, while another victim named Billy tried to climb up to the barred window using a stray wire. They, along with other victims, detail these attempts to Finney over the disconnected phone, hoping that he will be the one to finally make them work. To them, Finney represents the freedom they never got to experience, the lives they didn't get to live. Towards the climactic final scene, one victim named Robin, who audiences previously saw standing up for Finney against a trio of bullies, is able to pull him from the depths of hopelessness.

Although he was not able to save their lives, he has the ability to make their souls rest peacefully if he kills the Grabber. It is this encouragement, along with a dirt-packed phone and the leftover attempts at escape, that eventually helps Finney kill his captor once and for all.

Why this story matters

"The Black Phone" showcases something that seems to get lost when discussing actual crimes. Far too often, true-crime media jumps directly from discussing the victim to when they were found dead. This type of language dehumanizes the victim in the process, framing their death as an inevitability to boost the body count of their killer. When discussing their deaths in this way, it seems like they had no choice but to die, not resisting or fighting or trying to survive the hell they've suddenly been thrust into. This is why it can be detrimental when true-crime documentaries or podcasts focus on killers and their psychology rather than their victims, as it fiddles down their memories and retraumatizes their families, an experience detailed in an editorial from Time Magazine.

"The Black Phone" directly subverts this. In the original short story, only Bruce's spirit can contact Finney, where he suggests filling the phone with dirt and using it as a weapon. Changing it so that all of the Grabber's victims can contact Finney while also laying out an intricate series of potential escapes is something unheard of in our current crime-obsessed media landscape. Rather than building a mythos around the Grabber or trying to understand him, it builds itself around his victims, reclaiming their stories in the process.

It's all part of his game

It might seem easy to blow this off as a reach, there is more than enough proof that this framing was intrinsically weaved into the film's plot. In a recent interview, Hawke told /Film that he kept his preparation for the role to a minimum specifically because he wasn't trying to center the story around the Grabber. Furthermore, its prevailing comparison to "Stand By Me" highlights just how essential the connection is between Finney and the Grabber's other victims.

Perhaps the most significant evidence of this is the character of Max, an eccentric, coke-addled man who moved into his brother's Rocky Mountain home in order to solve the string of disappearances. Unfortunately, he doesn't realize that the answers he was searching for were right underneath his feet the entire time until it's too late.

There seems to be a prevailing idea that consuming true crime media or trying to become an armchair detective is cathartic, as theorized by the University of Washington School of Medicine. Sure, it might allow a viewer to relieve themselves of stress and anxiety, but to say that it gives you skills to prevent harm is flawed at best. No matter how much you think you understand a crime you never witnessed, you will never be able to face a real-life killer, a lesson that Max learns extremely quickly in the film.

Today's the day, motherf***er

It was a conscious decision to not allow the Grabber to become the main focus of the film, no matter how heavily the marketing featured him. By focusing the narrative entirely on Finney and the ghosts of his victims, the Grabber is appropriately seen as the monster he is; there is no need for psychoanalysis. This is a lesson that all true-crime creators, of both fiction and non-fiction alike, need to learn as well.

No matter how hard some documentarians or podcasters might try, it is intrinsically difficult to actually honor a killer's victims. This is because, as one Portland State University student puts it, determining what's ethical in the true-crime subgenre is a "sticky question." However, "The Black Phone" proves that one way to make this debate less complex is by preventing killers from becoming the primary focus. Not allowing them to control the narrative of the story, whether in a positive or negative light, could be the necessary step to creating a more ethical true-crime space.

You can only hope that, in the world of "The Black Phone," there are no podcasts or docuseries trying to examine the Grabber at a deeper level while separating his victims from their own stories. If so, then that means Finney saved their souls from torment only for the otherworldly pain to return, begging one question: What's the point?