The 10 Greatest Jaws Moments

Happy unofficial "Jaws" Day. There's already a "Star Wars" Day ("May the Fourth be with you," as the pun goes), and in recent years, celebrating "Alien" Day has become an annual event as well. Since those two franchises have got April and May staked out, let's just pretend that Steven Spielberg's "Jaws," the original '70s summer blockbuster, has its own commemorative day, recognized the world over.

The Great White Blockbuster that is "Jaws" first swam into theaters on June 20, 1975, so today actually is its birthday, and it's getting closer to turning the big 5-0. Though it might leave this three-day weekend feeling like a perfect storm of holidays (with yesterday being Juneteenth and Father's Day, also), we thought we'd mark the anniversary of "Jaws" this year by taking a look back at the 10 greatest moments from the film that made beachgoers afraid to go in the water, even as it kept long lines of moviegoers stretching down the block from the box office window.

Like its rogue, man-eating shark, "Jaws" is a "perfect engine," narrative-wise. It's chock full of memorable set pieces, and when you start narrowing those down to specific moments, exclusions are bound to happen. But these are the individual scenes, camera shots, and lines of dialogue that remain most firmly fixed in the mind of our metaphorical shark hunter — hired by the chief of police even as he deals with mayoral bureaucracy.

Rather than ranking the moments (Quint's USS Indianapolis speech would obviously be #1), we'll move through the film chronologically and take an in-depth look at how hitting these beats along the way helps the story progress. Without further ado, let's cast off on The Orca for a scenic boat trip through the 10 greatest moments from "Jaws."

Chrissie becomes the first victim

The music of John Williams, which Spielberg first dismissed as a joke, sets the immediate tone for "Jaws," as the film opens with the classic dun-dun dun-dun theme ramping up over the shark's POV. However, if you replaced Williams' score in that opening shot with, say, a calypso tune sung by a crab, you could alter the mood of it since there's nothing especially scary about what we see underwater.

The same cannot be said for what happens to Chrissie (Susan Backlinie), the shark's first unfortunate victim. As her campfire love connection, Tom Cassidy (Jonathan Filley), falls asleep drunk on the beach, Chrissie finds herself alone in the water with a movie monster. The thrill of potential romance, the exuberant run along the fence, the peeling-off of clothes to go skinny-dipping at sunrise, all give way to abject terror as the camera reverts to the shark's POV of Chrissie's backlit, kicking legs.

It has just found itself a meal. The scariest thing about this scene is the way Chrissie starts hyperventilating after the shark first tugs her down. Soon, it's yanking her all around and she's splashing and screaming, but Tom is still passed out drunk, and the floating buoy offers no sanctuary.

Chrissie has told us we're going swimming and invited us to, "Come on in the water," and now we realize just what that entails in the context of the cinematic experience. With this scene, "Jaws" announces itself in no uncertain terms as a thriller and a horror film where no swimmer is safe.

'We need summer dollars'

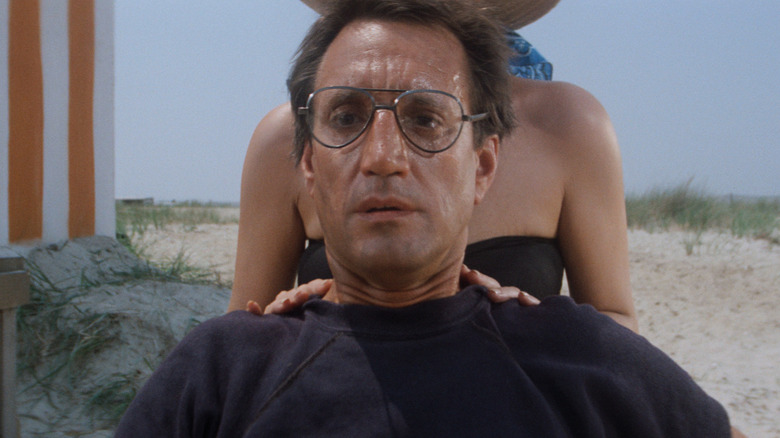

"Jaws" is perceptive about human nature, which can be petty and prone to denialism even in the face of societal threats. One of the most biting subplots — that doesn't feature any direct shark bites on the characters involved — centers on police chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) and his attempts to shut down the beaches and protect people from the shark. This brings him up against Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton), the mayor of Amity Island, who insists, "Amity is a summer town. We need summer dollars."

Vaughn delivers this line to Brody on a ferry, where he's accompanied by five other men. Two of them hang back as Vaughn, local reporter Meadows (Carl Gottlieb, who co-wrote the screenplay with "Jaws" author Peter Benchley), and the Medical Examiner (Robert Nevin) corner Brody. They don't want him acting unilaterally, doing things on his own authority, especially not when it would interfere with Amity's tourist trade. As the ferry moves out to sea, the men peel off one by one: first the Medical Examiner, then Meadows.

Soon, it's just Brody with Vaughn, the politician who proceeds to rewrite the story of Chrissie's death as a boating accident. Vaughn doesn't want to cause a panic on the Fourth of July, and that symbolizes so much. Islanders like him represent the capitalist side of America; they are the institution that confuses self-interest for self-preservation. In 2022, the waters are filled with tentpoles that seek to reproduce the commercial success of "Jaws" without internalizing its artistic lessons.

Vaughn will later tell the TV news camera, "Amity means friendship," but it's not always friendly to outsiders. Even people who live on the island but weren't born there, like Brody and his family, qualify as lifelong outsiders.

Dolly zoom on Brody

Irmin Roberts, a second-unit cameraman for Paramount Pictures, first devised the dolly zoom while working on Alfred Hitchcock's "Vertigo." There, it was used to give the dizzying sensation of looking down and experiencing vertigo — an effect achieved by zooming one way while simultaneously moving the camera along a dolly in the opposite direction. In "Jaws," Spielberg and cinematographer Bill Butler ("The Conversation," "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest") used a horizontal version of the dolly zoom to heighten Brody's reaction to the shark attack on young Alex Kintner (Jeffrey Voorhees).

The effect is preceded by another interesting bit of camerawork: the split diopter shot that allows us to see a man's head big in the foreground, with the small figure of an ocean swimmer in the background, both in focus at the same time. Mr. Taft (an uncredited Phil Murray) is talking to Brody, but all the while, Brody keeps looking over his shoulder, trying to play beach lifeguard, only to experience a couple of false alarms.

He interacts with one of them, an old man in a swim cap (Alfred Wilde, also uncredited), who joshes him about not going in the water. Brody dismisses him with the line, "That's some bad hat, Harry" (the namesake of the production company behind "The Usual Suspects" and "X-Men" movies).

People keep wanting Brody's attention, but he's preoccupied with nagging fears that the mayor and his rationalizations about Chrissie's so-called "boating accident" could not quell. When the shark swims in and turns Alex's raft into a fountain of blood, everything else falls away. The dolly zoom only lasts one or two seconds, but it's an indelible image that puts the squeeze on Brody, crystallizing the moment when his worst fears are validated and a child dies under his watch.

Quint makes his entrance

When Alex's deflated raft washes up in blood-red water on the shore, it leads straight into a scene at the county courthouse. The uproar in the council chamber where Amity's citizens are dealing with the fallout of Alex's death is disrupted by the scratching of nails on a chalkboard.

Enter: Quint, the working-class shark hunter played by Robert Shaw. The camera drifts across the crowded room to him, and suddenly, he's hijacked the whole scene.

With the way Quint sits there in his fisherman's cap and long sideburns, legs crossed, munching on a potato chip, saying, "I'll catch this bird for ya, but it ain't gonna be easy," he might initially come across as a caricature to some modern viewers. But keep in mind, this was before the Sea Captain on "The Simpsons" or any such parody.

As it is, Quint commands the attention of a room full of people, and Shaw breathes three-dimensional life into him beyond the retroactively amusing first impression he makes. There's a $3,000 reward for "the man or men who catch the shark that killed" Alex, but Quint ups the ante, outlining just how dangerous the shark really is and saying he'll do the job, but only for $10,000.

In this scene, Quint arrives to the party late, but he knows how to make a dramatic entrance and a well-timed exit. He even has his own entourage, which consists of one other mute fisherman and a dog on a leash. We can imagine a whole backstory with these guys sitting around on Quint's boat, fishing and drinking. Granular details like these add to the rich characterizations that have enabled "Jaws" to stand the test of time.

The false victory of the tiger shark catch

The arrival of out-of-town oceanographer Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) gives Quint's blue-collar boat smarts a well-educated, white-collar foil. It further validates Brody's fears and gets us even more on board with his view of Amity's predicament, as Hooper autopsies Chrissie and confirms that her death resulted from the "non-frenzied feeding" of an attacking shark that's "considerably larger than any normal Squalus found in these waters."

The size of the shark becomes a point of contention when a group of local fishermen string up a tiger shark they've caught, thinking this is the shark that killed Chrissie and Alex. It's a big fish with blood all over its mouth, and everyone — Brody included — gathers around, celebrating, shaking hands, and posing for a group photo.

Hooper, meanwhile, measures the shark's mouth and determines that it doesn't have a big enough bite radius (though it does eat fish and license plates whole, as we'll learn later). This causes conflict among Hooper and the fishermen, who don't take kindly to this city slicker ruining their moment.

It's a key moment in "Jaws," one that illustrates an early sort of "false victory," whereby the mission that drives the movie already seems to be accomplished. If only it were that easy.

As Hooper raises awareness of the truth about the tiger shark, Vaughn talks about how he's not going to cut the thing open and watch the Kintner boy's remains go spilling out all over the dock. Speak of the devil: as Vaughn looks up to see Mrs. Kintner (Lee Fierro) arrive in black mourning clothes. She slaps Brody across the face and lets him know she blames him for her son's death, at which point any sense of victory goes out the window.

'Michael's in the pond...'

The look on the face of Brody's son, Michael, played by child actor Chris Rebello, as he gets dunked in "the pond" — a shallow estuary that was supposed to be safe — is another lasting movie image that speaks to the inner child in all of us. "Jaws" warns us earlier that "most shark attacks happen in three feet of water," but the viewer might forget about that as the film misdirects them toward the main beach where the water is more crowded. Kids with a cardboard fin raise another false alarm there, while the dialogue downplays the pond as a place "for old ladies."

Michael isn't enthused when his safety-obsessed father confines him and his boat to the pond. Then, a shark spotter sights a real fin, definitely not cardboard, gliding his way. A man in a nearby rowboat, the Estuary Victim (Ted Grossman), goes into the water first, before the shark tips the boat with Michael and his friends in it.

It's here that we get our first real glimpse at the shark via a God's-eye shot of it, through the water, then briefly surfacing, as it snatches the Estuary Victim and leaves his blood bubbling up and severed leg sinking to the bottom. Michael is in now mortal danger — he could be the next Alex — and the stakes are realer than ever for Brody and the audience.

This scene pays off an earlier one with Brody and his wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary). At first, "Jaws" leaves open the possibility that Brody is overreacting and fixating on sharks too much, but when Ellen sees a picture of a shark biting into a boat while Michael is playing on one docked nearby, her swift change of heart gets the audience more on board with Brody.

'You're gonna need a bigger boat'

The American Film Institute voted this one of the greatest lines in movie history. The Alamo Drafthouse theater chain even came up with three different price tiers based on the line. And to think that it wasn't even in the script...

"You're gonna need a bigger boat" originated as a catchphrase on the set of "Jaws," as the crew had to deal with numerous problems, including a boat that wasn't big enough to pull a production barge, and the infamous mechanical shark, Bruce, which was constantly malfunctioning.

"Jaws," like any good movie, is about characters overcoming a series of challenges. In this respect, it mirrors the stressful working environment in which it was made. Even though there's blood in the water, the emergence of a 25-foot, 3-ton shark right alongside the boat as Brody is chumming catches him off guard and raises the stakes — in visuals and dialogue — for The Orca's whole hunting endeavor. Suddenly, it seems like a suicide mission.

Spielberg works up to it perfectly: Hooper is playing solitaire on deck, not a care in the world, while Brody is left to grumble about his bloody bait chore with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. Audiences are trained now to recognize the setup when you leave a character side frame in a monster movie with a lot of open space around them, but this trick was less well-worn in '75.

Withholding the cue of the shark's music theme, a trick employed in the third act, also heightens the scare. Bruce pops out and Brody pops up, his neck ramrod straight, as he backs through the wheelhouse door in shock and utters the line to Quint.

Quint's USS Indianapolis speech

There's a school of thought that "pure cinema" should uplift images and minimize dialogue, as if somehow transitioning out of silent films into talkies was a mistake and moving pictures should only ever show you things without telling you anything. While that may be a good rule of thumb to keep screenwriters from using dialogue as a crutch, "Jaws" shows that such rules were made to be broken.

Six years before "My Dinner with Andre," Spielberg sat men down at a dinner table in The Orca and had them comparing scars (including one broken heart) and telling — yes, telling — stories. It's all fun and games until a tattoo that Quint had removed becomes a conversation piece and he drops the name "USS Indianapolis."

All the air gets sucked out of Hooper's laugh and it leaves him catching his breath as the mood in the boat's wheelhouse immediately changes. Powered by Robert Shaw's acting and John Milius and Howard Sackler's screenwriting contributions, the ensuing three-and-a-half-minute monologue Quint delivers contains such vivid descriptions that the mind's eye takes over, filling in images where none are present except his talking head and Hooper's blurred listening form.

We can imagine the torpedoes slamming into the ship and 1,100 men going into the water after delivering the Hiroshima bomb. We can see the sharks' black doll eyes and the ocean turning red as they pick off six men per hour, leaving one man bitten in half and bobbing up and down in the water.

This scene, which is Spielberg's favorite, is the calm before the storm. No sooner does Quint conclude his monologue and the "Show Me the Way to Go Home" sing-along begin than we're back outside in the water as the yellow barrel denoting the shark's presence returns.

Farewell and adieu, Quint

Quint is Captain Ahab, and in the same way that "Moby Dick" ended with Ahab's ship sinking in a hellacious vortex, The Orca goes down and Quint goes with it. Of all the deaths in "Jaws," his is the most graphic and the most horrific because we're seeing a character we've come to know and care about get eaten mercilessly. And there's no looking away.

Quint slips from Brody's grip and the viewer even shares his POV, looking down into the shark's mouth as the fisherman slides toward it, his legs kicking on the edges of the frame. When the final burst of blood escapes Quint's mouth and the screaming is all over, the shark simply pulls him down into the water, and like that, he's gone. We switch to an over-the-shoulder shot from Brody's perspective, and the sea is quiet again.

Minutes earlier, there was a moment where Quint was left to ponder his ship taking on water and the sight of the lifejacket he'd never again wear while Williams' music dipped into the melody of "Spanish Ladies." This is the diagetic naval song that Quint sang earlier in the movie as if to suggest Hooper was doomed. We later see Quint smash the radio, putting an end to any distress calls and sealing his own fate.

The movie thus delivers a reversal of fortune with his death, since Hooper has swum to safety even after looking death in the eye and seeing it demolish his shark cage. In their absence, Brody is left to contend with the shark alone on a sinking ship in the final minutes of "Jaws."

'Smile, you son of a...'

The biggest moment of triumph in "Jaws" comes when Brody kills the shark, but first, he needs to take aim. He's perched on the mast, almost in the water, and has already missed several shots as he tries to land a bull's-eye on the scuba tank in the shark's mouth. Spielberg draws out the suspense and tightens on Brody as he finally lines up his last chance at a shot and says, "Smile, you son of a..."

It would be easy to go the full "son of a bitch" route à la John McClane's later "Die Hard" quote, "Yippee-ki-yay, motherf*****!" But the audience can finish Brody's sentence for him, just as it can imagine the shark before it ever comes onscreen (and picture the Indianapolis without seeing it at all).

Keeping in mind that we've just witnessed a shark eat a man alive, it's worth remembering that "Jaws" was rated PG. This was years before the Motion Picture Association of America instituted the PG-13 rating to bridge the gap between PG and R. It did this at Spielberg's suggestion after films like his own "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom" pushed the boundaries of what was PG-appropriate.

Stopping short of the b-word leaves room for another cloud of blood. Brody blows up the shark like Ripley blew the Xenomorph out of the airlock in "Alien." Yet, instead of drifting off into space like her, Brody comes back to shore and comes full circle to where he doesn't even hate the water anymore.

Hooper resurfaces, and hope is not just restored, but fulfilled. It's a happy ending that almost re-contextualizes Brody's "Smile..." line as one that Spielberg is directing at the viewer as he aims to deliver a crowd-pleaser with "Jaws" — succeeding 47 years over.