David Chase Wrote The Sopranos For A Very Personal Reason

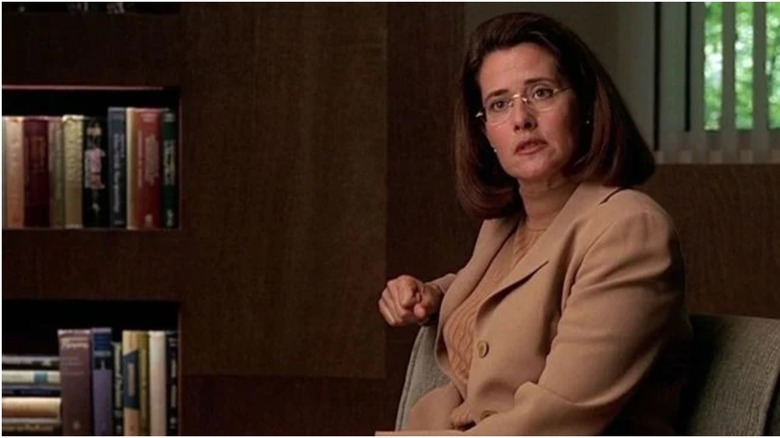

What sets "The Sopranos" apart from a litany of other mob movies and TV? Unlike "The Godfather" or "Goodfellas," the boss sees a shrink. The series' pilot opens with Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) having his first appointment with Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco). Seeking treatment for panic attacks, Tony remains Melfi's on-and-off patient until the end of the series.

Their sessions are a useful tool for the writers to let the audience inside of Tony's head; any monologue about his feelings is justified given the context. However, creator David Chase didn't include the therapy storyline just for convenient character development. He did it because one of the inspirations for "The Sopranos" was his own experiences in therapy.

A boy's best friend

Tony's mother Livia (Nancy Marchand) is based on Chase's own mother, Norma. Livia has no love for her son, or anyone, and is only able to see the negative in the world; her catchphrase is "Oh, poor you," the implication being that no one has it worse than her.

Interviewed for 60 Minutes, Chase said:

"I used to tell people stories about my mother and the things my mother said and did and everybody, my wife first of all, said someday you've got to write about her she's hysterical ... she was hysterical, but she was also hysterically funny. And I always thought how would you ever do that, and then I got the idea of putting it with a gangster because to see a tough guy like that have to contend with a tough woman like that might be interesting."

In that same interview, Chase confirmed that, while his mother never orchestrated a hit on him like Livia does Tony, she did threaten to stick a fork in his eye (recreated with Livia and Tony during a flashback in the episode "Down Neck").

On the "Talking Sopranos" podcast, Chase said that Nancy Marchand won the part because of how she channeled his mother's spirit:

"I looked at her like 'my God, that's my mother she's channeling my mother,' it was unbelievable ... the cadence, the attitude ... and all my family went nuts when they saw it. Right away. 'That's Aunt Norma!' That was just all her."

Thanks to Marchand's passing in 2000, Livia is only present in the first two seasons; she dies offscreen in "The Sopranos" season 3 episode "Proshai, Livushka," with much of the episode centering on her wake. However, her memory continues to haunt Tony, as the ghost of his own mother no doubt did Chase. After all, their relationship is what drove him to therapy.

Chase on the couch

Chase had worked in TV since the 1970s, most prominently as a writer on "The Rockford Files." Not content with TV, he aspired to direct films; indeed, he first conceived "The Sopranos" as a movie. According to "The Sopranos Sessions" (by Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall), even during the production of the pilot, Chase was secretly hoping HBO would pass so that he could turn the project into a movie then take it on the festival circuit.

Herein lies the irony of Chase's career. He revolutionized the medium he'd grown disillusioned with, and indeed, "The Sopranos" is a lynchpin moment in TV's usurping of film as "prestige" entertainment. However, he never quite became the film director he'd aspired to be.

Between these thwarted ambitions and his troubled upbringing, it's no surprise that Chase needed therapy. Speaking to The Guardian, Chase recalled how his mother's pessimism and depression had rubbed off on him, and it was his wife Denise who pushed him to seek help. His own stretch in therapy and lingering feelings about his family were the genesis for "The Sopranos." As Chase told Salon:

"People keep calling ["The Sopranos"] a story about a mobster with a midlife crisis, and maybe it's evolved into that. Actually, it's based on my own family dynamic — a guy who is in therapy because his mother is driving him crazy. But who cares about a TV writer and his mother? I began to apply my family dynamic to mobsters."

Chase did what great writers do; he took his own experiences and applied them to a different context to tell a compelling story.

Can therapy help?

In a 2006 interview with Rolling Stone, Chase confirmed that Melfi was modeled on his own therapist, Dr. Lorraine Kaufman. So, what did the talking cure do for him? In that same interview, he said:

"I think [therapy is] probably really good in the short term, and there are times when people just need someone to talk to. But the classic talk therapy that goes on and on and reinvestigates every aspect of your infancy just plays into a victim mentality ... Therapists never want you to leave. I don't know any who say, 'Go ahead, little bird, fly out of the nest.'"

How ironic that Melfi's story ends with her pushing her patient away. As "Sopranos" writer Terence Winter explained, Chase became aware of psychiatric study "The Criminal Personality," which argues that therapy teaches criminals not to fix their behavior, but how to rationalize it. Chase decided the study would spell the ending for Tony and Melfi. In penultimate episode "The Blue Comet," Melfi's own doctor Elliot Kupferberg (Peter Bogdanovich) points her to the study. Reading the study, Melfi discovers a lot of overlap with its findings and her sessions with Tony. Thus, his sway over her is finally broken and she realizes he's beyond help; their next session is their last.

The cap on Melfi's story reflects the clear-eyed view on therapy in "The Sopranos." In the years since the show went off-air, therapy has become even more socially acceptable. This is undoubtedly good, but it's been coupled by a tendency to treat the process like a silver bullet; walk in and you get what's plaguing your mind erased "Eternal Sunshine" style. Chase understands that identifying your problems and their roots is only half of it. The onus ultimately falls on the patient to make adjustments. The flaw in his characters is that none of them are willing to change.