The Daily Stream: He Got Game Is Basketball Poetry In Motion And An Essential Spike Lee And Denzel Washington Collaboration

(Welcome to The Daily Stream, an ongoing series in which the /Film team shares what they've been watching, why it's worth checking out, and where you can stream it.)

The Movie: "He Got Game"

Where You Can Stream It: Hulu / Paramount+ / DirecTV / Epix

The Pitch: A convicted felon receives one week of parole to convince his son, the nation's #1 high school basketball prospect, to play for the governor's alma mater.

In "He Got Game," when NBA star and first-time actor Ray Allen looks the viewer in the eye and says basketball is "like poetry in motion," he might as well be talking about Spike Lee's filmmaking aesthetic and the fluidity of Barry Alexander Brown's editing. "He Got Game" begins with a musical overture and a flow of impressionistic images that set the stage for a sports movie with the scope and lyricism of an American epic.

Lee had already made one epic with Denzel Washington in "Malcolm X." This film marked their third collaboration including "Mo' Better Blues," and they would team up again for a fourth time in "Inside Man" before Lee gave Washington's son, John David Washington, his breakthrough in "BlackKklansman." Here, Washington's character, Jake Shuttlesworth, is a pawn of the prison-industrial complex, who can only hope to pass the ball to the next generation. Another sports pro turned actor, Jim Brown, plays one of his parole officers, and they keep him on a short leash — or in an electronic ankle tag, as the case may be.

Music adds so much to this movie — the soundtrack is by Public Enemy, and it's a good one. Lee also re-contextualizes the classical compositions of Aaron Copland using an unlikely selection such as "Hoe-Down" from the ballet "Rodeo" to bring out the exhilaration of a pick-up game.

Why it's essential viewing

With cinematography by Malik Hassan Sayeed, this is one of those films where its composition is so beautiful that you could isolate almost any image and have it be a meme-worthy One Perfect Shot. "He Got Game" is another good pick for Black History Month — or any month — and it's a film that is highly underrated or at least went under-seen in its day.

Though it holds solid 81% and 83% critic and audience scores, respectively, on Rotten Tomatoes, "He Got Game" failed to break even at the box office in 1998. It had a $25 million budget, the same as "The Shawshank Redemption" (which it name-drops), but it didn't have the benefit of an Academy Awards push and a theatrical rerelease behind it, as "Shawshank" did.

Those who have seen it may have caught it on TV or home video first. Edward Norton, who did receive an Oscar nomination the same year for "American History X," was a fan. He went on to star in Lee's "25th Hour," and called "He Got Game" an "under-appreciated masterpiece."

He speaks the truth, and not enough people seem to know it. To add insult to box-office injury, something called the Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, which sounds like an off-brand version of the Razzies (because it was?) nominated Lee for Worst Director of 1998, right alongside Wesley Snipes for Worst Actor for the trailblazing superhero film, "Blade." Is there an inverse #OscarsSoWhite pattern there, or am I crazy?

Keep in mind, the Razzies themselves nominated Stanley Kubrick for Worst Director for "The Shining." Half the time, they don't know what they're talking about — and neither do I when it comes to sports. Beyond little league baseball, the only sport I ever really cared about was basketball. "He Got Game" hit the year of the historic Chicago Bulls – Utah Jazz match-up at the NBA Finals, as seen in the 2020 ESPN documentary, "The Last Dance."

Jesus (Shuttlesworth) saves

New York is baked into the fabric of "He Got Game" from the first frames when we see someone shooting hoops with the island of Manhattan and the Twin Towers still standing in the background. Coney Island is the main setting, but Lee's crew also shot on location in Chicago's Cabrini-Green housing projects, where "Candyman" was set and filmed.

The first time I saw this movie, I was in pre-seminary college in a suburb neighboring Washington's hometown of Mount Vernon, New York. Unlike his father, a Pentecostal minister, I didn't follow through with the whole seminary thing. But I absorbed enough to get biblical with the themes of "He Got Game," a movie that is drenched in religious hyperbole.

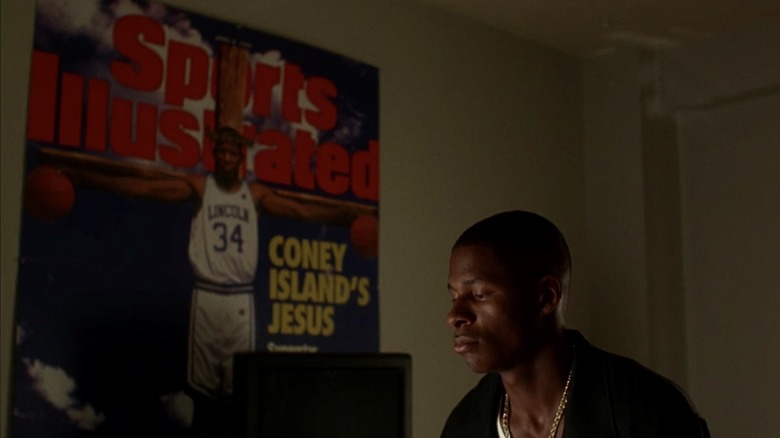

In the film, sports commentators speak of Allen's high school basketball sensation, Jesus Shuttlesworth, in ecstatic terms, as if he were the Second Coming of Michael Jordan (who cameos at one point, just long enough to say the film's title to the camera). "Jesus is the best thing to happen to the game since the tennis shoe was invented," says Georgetown coach John Thompson.

Though it's inspired by Earl "Black Jesus" Monroe, Jesus himself isn't a fan of his name. As a kid, it was an embarrassment to him every time his mother leaned out the window and called him in for dinner. "People used to think she was some type of religious freak or something, catching the Holy Ghost," he complains to Jake, who accidentally killed Jesus' mother one night and thereby landed himself in prison.

Jesus is on track for greatness, but he's assailed by hangers-on and temptations: a montage of drugs, alcohol, gambling, gun violence, and sex, any one of which could derail his promising sports career. Big Time Willie (Roger Guenveur Smith) acts as a sort of live-action Lampwick, cruising him through the potentials of Pleasure Island in his convertible.

Everybody wants a piece of Jesus

Since "He Got Game" quotes the Ten Commandments outright ("Thou shalt not kill," Jake), it would be easy to think the entire film is one long game of breaking the second or third commandment (the one about taking the Lord's name in vain). The name Jesus is even moaned in a graphic ménage à trois that took a friend of mine by surprise, if only because they happened to be watching the movie with their mother.

However, if you take it at face value and consider that Lee is deliberately invoking the name Jesus, again and again, his dialogue has an interesting effect. Subtextually, the line between Jesus Shuttlesworth, the character, and Jesus Christ, the religious figure, becomes so blurred that, at a certain point, when the viewer hears the name "Jesus," their head is swimming and it's no longer clear who the subject is.

Maybe it's both Jesus S. and Jesus C. Lines take on double meanings, while the film as a whole begins to read, on one level, like a commentary on the self-serving nature of people's relationship to God (or their concept of God, if they have one).

Everybody wants something from Jesus. You might as well call him Jesus Christ B-Ball Star. They're coming at him from all sides, clutching at his robes like lepers, each trying to steer this young man in the direction of a college team that will benefit them. Jesus himself just wants to do the Lincoln roll call in the locker room with his boys, rapping, "My name is Jesus / I am the man / What's up with these questions? / About my plan."

As he is sitting in the office with his unctuous coach, Jesus remarks:

"People don't care about me. They care about themselves. I mean, they're just trying to get over, trying to get a piece of Jesus, that's all."

'Jesus? I love you'

Elsewhere, Jesus addresses the hypocrisy at the root of some public professions of faith:

"Everybody and their mama's running around saying they're born again. Especially all these athletes and entertainers. They got caught smoking crack in the hotel..."

At one point, Lala (Rosario Dawson, in a breakout role) is on the phone with Jesus, telling him she loves him, even as another man's hand reaches into the frame and caresses her. She's as unfaithful to him as the avowed faithful are to God by dint of original sin, the theological premise whereby corruption is universal among humans.

Members of sports teams (or political parties, or whatever group) pray to Jesus C. on behalf of what they want, and it recalls that Civil War movie quote from "Cold Mountain," where Jude Law's character says, "I imagine God is weary of being called down on both sides." Jesus S. makes a similar observation in "He Got Game" when he asks, "How come you never hear Jesus being praised in the losers' locker room?"

"He Got Game" indulges in a few excesses, with its male gaze sometimes divorcing women's bodies from their faces. I'm not sure the movie's gender politics always balance out, or maybe it's just that Milla Jovovich isn't always up to Washington's acting level as she tries to lend her (literally) pimp-slapped Hitchcock blonde character credibility. That said, "He Got Game" ends on a moving note, and it has verve, humor, and heft that might make even a Booger "feel handsome."

A fixture courtside at Knicks games, Lee saw screen presence in Allen, then a Milwaukee Buck, and offered him the Jesus role at halftime. He not only led the way for fresh faces like Allen onscreen; he also led the way for other filmmakers of color like M. Night Shyamalan. "He Got Game" was Lee's last great 20th-century film, and it's an overlooked yet no less essential piece of '90s cinema that deserves a revisit.