A Brief History Of Black Filmmakers

As a Black person and film enthusiast, I recently realized there was a pretty big gap in my personal knowledge of Black filmmakers. Sure, like most people, I can name a handful of well-known contemporaries, with the size shrinking or increasing based on how you choose to define "well known" — there are plenty of overlaps, but my lived experiences have shown there are sometimes differences between being a Black household name and being more decidedly "mainstream" (which is a more diplomatic way of saying white people can also recognize you).

Anyone who calls themself a movie lover can easily name Spike Lee, Ava Duvernay, Ryan Coogler, and Jordan Peele, all of whom are still very much active and alive today, but how many of us can name historical Black directors who are no longer with us in the same way we can easily recall late greats like Alfred Hitchcock or Stanley Kubrick? And what about the Black contemporary filmmakers who aren't members of the elite, mainstream handful?

It is with this in mind that I decided to dive into the history of Black filmmakers so that I and anyone who cares to read can expand on what should be essential knowledge for any self-respecting film nerd. As it turns out, this history is a rich and fascinating one filled with both notable and unsung heroes, ambition, controversy, and the success of creating and contributing to the art of film despite the odds. While it would take an entire dedicated textbook to begin to cover it all, here are some of the ones I personally found to be the most interesting.

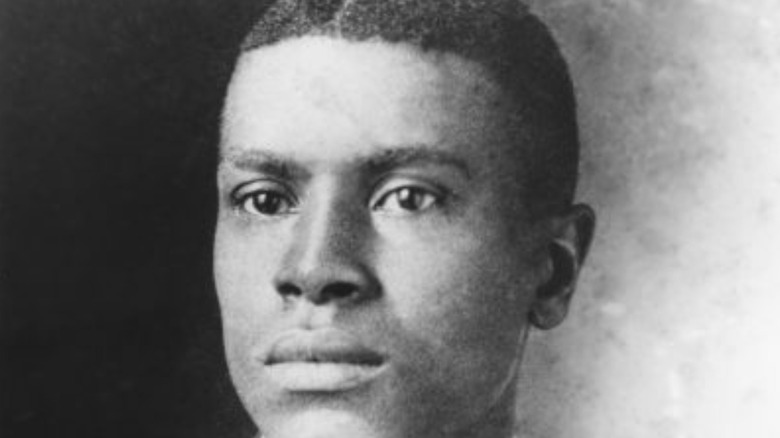

Oscar Micheaux

Oscar Micheaux is regarded as the first major Black American filmmaker for writing, producing, and directing over 44 films between 1919 and 1948. The majority of Micheaux's films were part of a genre known as "race films," which were movies featuring predominantly Black casts produced primarily for Black audiences.

Micheaux's success in filmmaking is particularly impressive given that it was created during a period of rampant racial hostility that put Black people in every walk of life at a systemic disadvantage, and the young film industry was no exception. Micheaux's work was produced independently rather than in the budding and discriminatory Hollywood studio system. His first movie, "The Homesteader," was a film adaptation of his first novel. Like all of his subsequent work, "The Homesteader" drew upon his personal experiences as a Black person in the U.S., as well on the tumultuous and complex state of inter-and-intra-racial relations in the country during his lifetime. The film was financially and critically successful.

His second film, "Within Our Gates," proved to be more controversial than his debut film, so much so that it was initially rejected by the Board of Censors in Chicago due to fears that its stark, realistic depictions of the violence Black Americans faced at the time. Notably, the film made a point to touch on the still-taboo topic of sexual violence against Black women while simultaneously debunking the false and racist ideology that Black men were all rapists who were obsessed with white women, which was used to justify the horrific lynchings of countless innocent Black men and boys. Despite the controversy that comes with honest storytelling, the film drew crowds when it was finally released.

Not only was Micheaux the first notable Black filmmaker, but he was also one of the first notable U.S. filmmakers in general, seeing the potential of a new industry as a means to achieve personal success and societal change by delivering powerful messages about the complexities of Black identity in America. While the general public still doesn't know as much about Micheaux as they probably should, his contributions and significance as a film pioneer continue to be recognized posthumously. In 1992, the Library of Congress selected "Within Our Gates" for preservation in the National Film Registry, an honor reserved only for films that are deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." He had also previously been awarded the Golden Jubilee Special Directorial Award by the Directors Guild of America 1986, and given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1987.

The forgotten history of Black women in the early days of film

The film industry has been historically tough for women to break into as filmmakers, and especially so for Black women. Even so, there are records dating back to the earliest days of filmmaking that reveal Black women have always been part of the industry, both on and offscreen. While there is some debate about who the first Black woman filmmaker is, Tressie Souders is often credited as the first known one. Born in 1897, Souders eventually wrote, directed, and produced "A Woman's Error," her only known film in her early 20s. "A Woman's Error" was distributed by a Black-owned film distributor in Kansas City, Missouri in 1922, and unfortunately there are no known surviving copies of the film, though there are records of its existence. The following year, another Black woman filmmaker named Maria P. Williams would release "The Flames of Wrath," a film she directed, produced, and starred in.

William Greaves

William Greaves began his film career as an actor in 1948, but quickly became dissatisfied with the limited, stereotypical roles afforded to Black actors at the time. As a result, he decided to pursue filmmaking as a writer, director, and producer, and would eventually be recognized as one of the most influential independent Black filmmakers and documentarians in history. Like Micheaux, Greaves centered blackness in his work, focusing on depictions of important historical figures like Ida B. Wells and Frederick Douglass, as well as on. He is also the director and producer of the 1968 avant-garde meta-documentary "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One," described on the official William Greaves website as follows:

It's 1968 and Greaves and his crew are in New York's Central Park ostensibly filming a screen test. The drama involves a bitter break-up between a married couple. But this is just the "cover story." The real story is happening "off" camera as the enigmatic director pursues his hidden agenda. The growing conflict and chaos—accompanied by moments of uproarious humor—explodes on screen, producing the energy and the insights that the director is searching for.

Greaves uses multiple cameras, mixes cinéma vérité and conventional shooting styles and experiments with a variety of other cinematic techniques, including the use of simultaneous split-screen images. The result is a film with multiple levels of reality that reveals, and comments upon, the creative process.

Also like Micheaux, Greaves would have his film selected for preservation by the Library of Congress as well. In addition to "Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One," Greaves would go on to produce over two hundred documentaries during his lifetime, more than half of which he also wrote and directed. Additionally, he won an Emmy for his work as a director, producer, and co-host of the show "Black Journal," in 1969. Much of his work features realistic and nuanced depictions of Black life and identity in America, offering meaningful media representation outside of stereotypes and one-dimensional tropes.

Key filmmakers of the blaxploitation era (1970s)

The blaxploitation film era was a period that took place during the 1970s. As the name suggests, it is a portmanteau of the words "Black" and "exploitation," and a subgenre of the exploitation films that rose to prominence during the same time period. While the genre is controversial due to its inherently exploitative nature in depicting Black Americans as largely negative stereotypes while simultaneously attempting to appeal to the same audience it is stereotyping, Black filmmakers like Gordon Parks and Melvin van Peebles rose to prominence during this time.

Where previous Black directors like Micheaux and Greaves worked outside the confines of Hollywood, Parks became Hollywood's first major Black director with the 1971 release of "Shaft." Before he became a director, Parks had already earned a reputation as a respected photographer who specialized in both documentary photojournalism and glamor photography. His contributions to both film and photography have been recognized and archived by the Library of Congress multiple times, and in 2000 he was awarded the prestigious title of "Living Legend," which was created to honor "individuals who have made significant contributions to America's diverse cultural, scientific and social heritage." Spike Lee has credited Parks as one of his inspirations.

As for Peebles, while his first feature film, "The Story of a Three-Day Pass" won a Critics Choice Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival, it wasn't until 1971 that he gained mainstream success with "Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song," which he wrote, directed, produced, and starred in. Both Parks and Peebles are credited with creating the Blaxploitation genre.

William Crane is another notable Black filmmaker of this period, having directed the 1972 horror film "Blacula," in which an African prince asks a racist Count Dracula for help in ending the slave trade, only to be turned into a vampire as a result. While "Blacula" received mixed critical reception, it was still one of the highest-grossing films of the year and even won a Saturn Award for Best Horror Picture. In 1976, Crane directed another horror-themed blaxploitation film entitled "Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde," and went on to direct a number of other films and television shows spanning a variety of genres and interests (including "The Dukes of Hazzard," tv series which is very interesting to me, personally).

Although the blaxploitation genre remains a topic of controversy, it is notably the second time in the history of the American film industry — with the first being the "race films" of Micheaux's lifetime — in which Black people were regularly producing, directing, and starring in feature films. Several contemporary directors, including Quentin Tarantino, have also cited the genre as an influence in their work.

Dee Rees

In 2011, Dee Rees's first feature film "Pariah" debuted at the Sundance Film Festival. Written and directed by Rees — and executive produced by her mentor renowned Black filmmaker Spike Lee — "Pariah" received critical acclaim and several awards, with many pointing out how it was a rare depiction of a Black protagonist's journey with sexuality, as it tells the story of a Black teenage girl embracing her lesbian identity. Rees, who is also a lesbian, has stated that "Pariah" was "semi-autobiographical." Since the debut and success of her first feature film, Rees also wrote and directed a number of films including the 2017 historical drama "Mudbound," which received several Oscar nominations, including "Best Adapted Screenplay." In 2020, it was reported that Rees would be writing and directing a film adaptation of the controversial play "Porgy and Bess."

And now for some personal faves

I could continue to write a semi-chronological list of every documented Black filmmaker I find interesting, but instead, I'm going to finish this up with two of my personal favorites and hope I've inspired you to seek out more on your own.

While Issa Rae works primarily in television rather than film, it would be criminal of me not to include her. I first became familiar with Rae's work when she was still producing her web series, "Awkward Black Girl." In addition to being hilarious, it was the first time in my life that I saw such a relatable Black girl and main character in a series. Rae went on to produce and star in the popular HBO series "Insecure," another extremely relatable show. She has used her influence and success to uplift others in the tv and film industry, and was named one of Time's 100 most influential people in the world in 2018. Since this article is technically about filmmakers, I am qualifying her mention by pointing out that she served as executive producer for the 2020 romantic drama "The Photograph" and 2020 romantic comedy "The Lovebirds," both of which feature Rae as a main character and romantic lead in two genres that tend to exclude Black women from leading roles.

Next, there's Robert Townsend. Robert Townsend directed the 1991 musical drama — and one of my personal favorite movies — "The Five Heartbeats." Is it the best movie ever made? No. Is it a bit cheesy at times? Absolutely, and I love it. It's an earnest labor of love, as Townsend financed the production of the film with his own money and maxed out his credit cards in the process. Although it was not exactly a critical success upon initial release, it eventually achieved a cult following among Black audiences. Prior to "The Five Heartbeats," Townsend wrote, produced, and directed 1987 satirical comedy "Hollywood Shuffle," which received much better reviews and was awarded the International Critics' prize at the 1987 Deauville American Film Festival. Townsend continues to work in the film and television industry today, most recently directing an episode of "The Wonder Years" reboot as well as episodes 3 and 4 of the 2021 Netflix series "Colin in Black and White."

In addition to my nostalgic fondness for Townsend, another one of my favorite Black filmmakers is Jordan Peele. His successful pivot from long-time comedian to well-respected horror director is honestly just impressive as hell. Clearly, I'm not alone in my fangirling of Peele, as he's garnered a wealth of critical acclaim and success since the debut of "Get Out" in 2017, for which became the first Black writer to win an Oscar for Best Screenplay.

I just won an Oscar. WTF?!?

— Jordan Peele (@JordanPeele) March 5, 2018

It's beyond exciting to see a Black person quickly become so influential in the horror genre, and to see him routinely casting unambiguously Black actors and actresses in his films — because let's be honest for a sec and acknowledge that horror movies aren't exactly known for their on or offscreen racial diversity as the genre has been historically plagued by racial stereotypes, tokenism of Black characters (and other people of color), and the whole "black guy dies first" trope.

Despite these issues, horror is a genre I adore, and I find Peele's blossoming legacy to be nothing short of inspiring. It also goes without saying that his movies are also just really f*****g good, regardless of how passionate you are about the intersection of race and representation in the horror genre and film industry at large. I mean, I haven't even been able to stop thinking about the "Nope” trailer since it first dropped, and I really don't know how I'm supposed to keep myself busy between now and its July 22, 2022 premiere date.