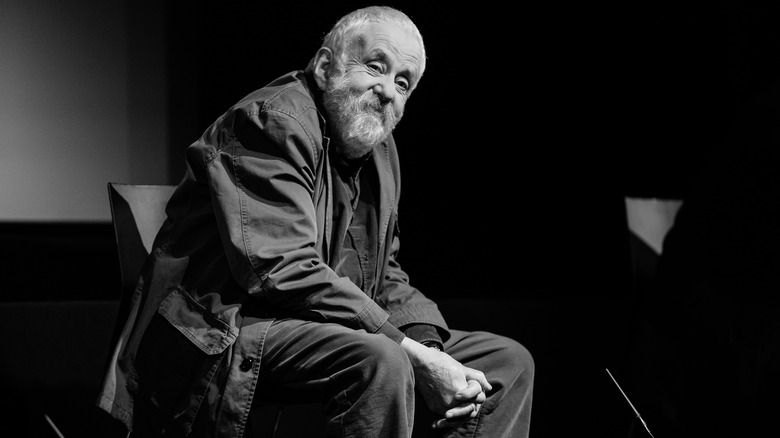

Filmmaker Mike Leigh Can't Find Funding, Reveals Netflix Turned Him Down

In a recent interview with iNews, Mike Leigh revealed he has been having trouble finding funding for his films.

Leigh has been nominated for seven Academy Awards, 15 British Academy Awards, and has won the Palme D'Or at Cannes, plus many other accolades besides. His filmography stretches back to 1971 and contains 15 excellent feature films. He is often hailed as one of the filmmakers who popularized "kitchen sink realism," often telling down-to-earth tales of the British working class, and his films have regularly topped critics' best-of-the-year lists since the beginning of his career. He exploded on the American indie cinema scene in 1993 with his hard-hitting film "Naked," gained attention from the Academy in 1996 for his film "Secrets & Lies," made one of the best musicals of all time in 1999 with "Topsy-Turvy," broke everyone's hearts with "All or Nothing" in 2002, examined the state of abortion in England with 2004's "Vera Drake" ... I could go on. His last film, "Peterloo," about the 1819 massacre at Manchester, was released in 2018.

Evidently, the people at Netflix — and other financiers — don't care about any of this.

Fund This Man's Projects

In the iNews interview, Leigh bemoaned his inability to find funding for his projects. He also seems to intuit why; Many of his films are close collaborations with actors, and often he will invent characters and entire films based on the personalities of his cast. This was certainly true of his 2008 comedy "Happy-Go-Lucky," which he conceived with actress Sally Hawkins. As such, when pitching a movie to studios, Leigh speaks in broader strokes than they may be comfortable with. If he can't provide specifics — which he doesn't have yet — he is rejected. Often, he simply won't tell outright.

"People want to know what it is and why it is," Leigh said.

"Netflix just turned me down, which is a shame, because they have plenty of money. They said they couldn't possibly contemplate backing it without knowing who the cast is or what it's about. It's nonsense because if they made it, people would watch it – because it would be there."

This was a change from Leigh's experience with making "Peterloo" which was partially funded by Amazon. He ultimately turned in a film that was 20 minutes longer than contracted, but Amazon still distributed it and largely stood out of his way during production. Indeed, throughout his career, Leigh has managed to find distributors that allow him to work the way he wants to, and he is accustomed to a great deal of creative freedom on his films; why hire Mike Leigh if you don't want a Mike Leigh film?

Mike Leigh Doesn't Make Expensive Movies

Netflix's stinginess with Leigh is genuinely baffling, given how often they hurl fistfuls of money at other projects. Not only did Netflix distribute a $200 million cup of room-temperature wallpaper paste in the form of "Red Notice," but they frequently fund high-profile awards contenders and auteur-driven prestige pictures like "Roma," "The Irishman," "Da 5 Bloods," "Mank," and "The Power of the Dog." Mike Leigh would fit right into that latter crowd and offer the studio an opportunity to submit even more of their feature films to the Oscars (if awards attention is a primary concern).

More importantly, the studio would be distributing a film by one of the most celebrated English directors of his generation. Indeed, if Netflix were feeling extravagant, they could offer Leigh enough money to make another elaborate and opulent period piece in the vein of "Peterloo" and "Topsy-Turvy." Even if they're not, Leigh's films are rarely pricey: they usually cost under $20 million.

But then, Netflix's funding and distribution model has long been baffling in general. They have infamously purchased high-profile films from other production companies, only to release them on their streaming service with no fanfare or advertising whatsoever. To Netflix, "Red Notice" and "The Woman in the Window" are all equal in that they take up space on their servers, and might attract new subscribers. Their half-awake, laissez-faire distribution decisions feel like a James Joyce-ian stream-of-consciousness miasma of random insights. Surely, Mike Leigh would be invited.

Perhaps He's Too British? No.

A look at Mike Leigh's broader scope of work will reveal a wide variety of topics and styles across several genres. Despite this — and likely because of the power of films like "Meantime," "Secrets & Lies," "All or Nothing," and "Life is Sweet" — Leigh is still pigeonholed as a filmmaker often associated with a single style and singularly British concerns. This is true to an extent, in that he makes films about English history, English historical figures, and English citizens, but his films are not so English that American audiences would not fall in love with them. In Q&A's and interviews, he challenges the notion that he's just a kitchen sink realist or just a leftist. He is those things, and many more things besides.

"People talk about my films having English specificity and, of course, that's the milieu," Leigh said in the iNews interview. "But first and foremost, my films are about life."

Perhaps He's Too Political? No.

Leigh's films — like all art — most certainly have an openly political bent. "Peterloo" was about a key moment in the labor movement in England. "Vera Drake" was about a woman who performed back-alley abortions in the 1950s and how that was seen as a compassionate act, even if it was illegal at the time. Many of Leigh's films center on class. "All or Nothing" is about the struggle of the working classes and how difficult it is to express love for one another when financial necessity gets in the way. "Another Year" is at least partially about how getting older is a different experience for people with and without money. Leigh has a point of view, and it comes out in his work.

But Leigh is no Ken Loach and has spoken out against any sort of singular definition to his work.

Again, from the iNews interview, Leigh puts the blame on how ideas about art are spread in the modern world:

"Because of social media, the circulation of simplistic, easily digestible, crude ideas can be disseminated. It is great that diversity is an issue and is being understood on all sorts of levels. But, of course, there is a flip side to that. It spills into fascist box-ticking culture. Somebody asked me the other day, at a Q&A, whether I thought 'Naked' could be made now."

"I would hope so."