5 Movies From 1969 That Define Western History

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 1939 John Ford surprised everyone, John Wayne included, by casting the then up-and-comer in "Stagecoach." Though he initially faced major pushback for not casting an established star in the role of Henry, the Ringo Kid, Ford clearly knew what he was doing. As did the Duke himself, who shot to stardom in the wake of the film's release. But "Stagecoach" did more than establish Wayne as an A-lister. It revitalized a genre that had been almost exclusively relegated to B-movie status during the 30s. With "Stagecoach," Ford proved that the oater could be used to tell stories that went beyond mere action and adventure clichés, sparking renewed interest and popularity.

Exactly 30 years later, we would see what was arguably the peak of that renewed popularity. 1969 gave us so many classic Westerns that it's essentially the apex of what was once the biggest, most reliably popular genre in the world. This was the year John Wayne finally won an Oscar, Sam Peckinpah gave us a brutal revisionist classic, and Clint Eastwood made an unconventional Western that he might regret but which remains culturally important to this day. Viewed in retrospect, 1969 was a final defiant flourish that preceded the Western's rapid decline in the 70s.

So seminal was 1969 that it's tough to even pick five of the most defining Westerns of that year. But here we are, faced with that momentous task and, like the great gunslingers of Western history, ready to do battle despite impossible odds. Read on for the full shootout as we try to narrow down a list of the most influential oaters of '69.

True Grit

John Wayne is a titan of cinema that made his name in Westerns, but it took him a full 40 years to win an Oscar. That moment finally came with the Henry Hathaway-directed "True Grit," a movie in which the Duke seemed to finally acknowledge his status as an aging star who prior to this movie was becoming somewhat of an anachronism as the Western genre evolved past his more simplistic good guy cowboys.

In "True Grit," an adaptation of Charles Portis' novel of the same name, Wayne embraced and even poked fun at his age as the hard-drinking U.S. Marshal with a heart of gold Reuben "Rooster" J. Cogburn. Tasked with accompanying Mattie Ross (Kim Darby) on her quest to find the man responsible for killing her father, Cogburn initially clashes with the youngster and their fellow traveler, Glen Campbell's Texas Ranger La Boeuf. But by the end he more than proves his worth as a still-capable gunslinger, thereby reminding audiences that Wayne himself still had it.

"True Grit" also became the blueprint for the rest of John Wayne's career, prompting the veteran star to branch out from his more formulaic work of previous decades and make bold new choices. Well, bold for him, anyway. Wayne wasn't exactly embracing the revisionist ethos of the new crop of Westerns, but he was finally playing characters with more nuance — men who were flawed and who weren't afraid reflect on their past and by extension the history of the Western itself. That was significant for the genre because it emphasized the already palpable sense that oaters were undergoing a significant evolution, and thanks to "True Grit," Wayne got to go along for the ride until his death in 1979.

The Wild Bunch

With this 1969 classic, director Sam Peckinpah created one of a handful of quintessential revisionist Westerns everyone should watch at least once. But if you want to know why "The Wild Bunch" was so influential beyond the ahead-of-its-time editing, stellar writing, and brilliant performances, consider that John Wayne hated this controversial Western with a passion.

This was not a good-guys-vs.-bad-guys shoot 'em up but a surprisingly violent Old West epic designed to shake audiences out of their desensitization to violence. At the time, the Vietnam war was raging, and just a year prior, with the help of the government, Wayne had made one of his worst and most controversial movies in the unapologetically jingoistic "The Green Berets." That regrettable entry in the Duke's filmography sought to drum up support for the war in Indochina. "The Wild Bunch" was the anti-"Green Berets." As noted in "If They Move... Kill 'Em!: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah," the director explained his intention to "take this façade of movie violence and open it up [...] and then twist it so that it's not fun anymore, just a wave of sickness in the gut."

The film that resulted from this aim follows a group of outlaws that includes Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine) and brothers Lyle (Warren Oates) and Tector Gorch (Ben Johnson). Led by Pike Bishop (William Holden), the gang plan one final job in 1913 Texas but discover they've been set up by Bishop's ex-partner Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan). "The Wild Bunch" ends with a gruesome finale that was as brutal to film as it is to watch, and which hammered home Peckinpah's point about violence. In so doing, it reminded viewers that Westerns could be much more than just simplistic adventure.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Paul Newman and Robert Redford playing outlaws in the top-grossing film of 1969 not only made for a defining Western but a defining moment in cinema. Critics didn't love "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" when it first debuted, but the film's legacy speaks for itself.

Directed by George Roy Hill, the film sees Newman portray Robert LeRoy Parker, aka Butch Cassidy, who alongside his partner Harry Longabaugh, aka the "Sundance Kid" (Redford), carries out two train robberies that immediately make the pair the focus of a crack team of lawmen. This posse then pursues Cassidy and his sidekick relentlessly, following them across borders and eventually facing off against them in a final shootout that we never see play out but which almost certainly spelled death for the titular pair.

"Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" wasn't a revisionist Western in the sense that "The Wild Bunch" was. This wasn't a violent deconstruction of the Old West myth. But with its mix of styles and tones it appealed to the countercultural views of contemporaneous audiences. At first, the classic song in "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" had a whole lot of haters, Redford included. That song, "Raindrops Keep Fallin' on My Head," appears in an infamous scene in which Redford's outlaw takes Katharine Ross' Etta Place for a ride on his bike. It was criticized at first but eventually came to be seen as an extension of the film's willingness to play with the tone of a more traditional Western. That willingness made this unorthodox oater a major hit and one of the most important films of the year, the decade, and as its appearances on multiple greatest films lists has proved, of all time.

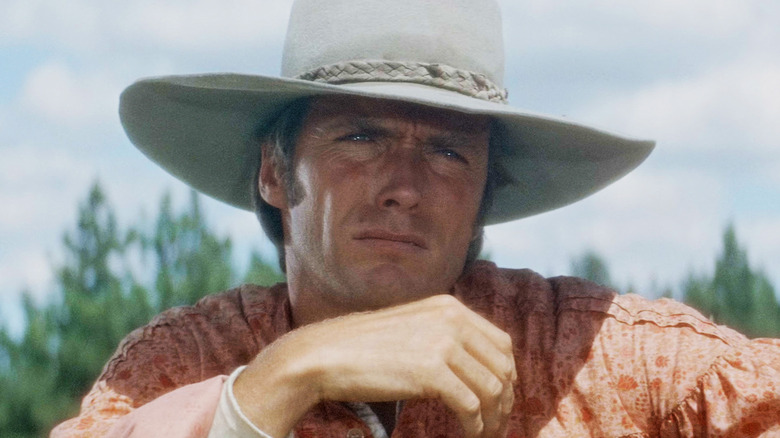

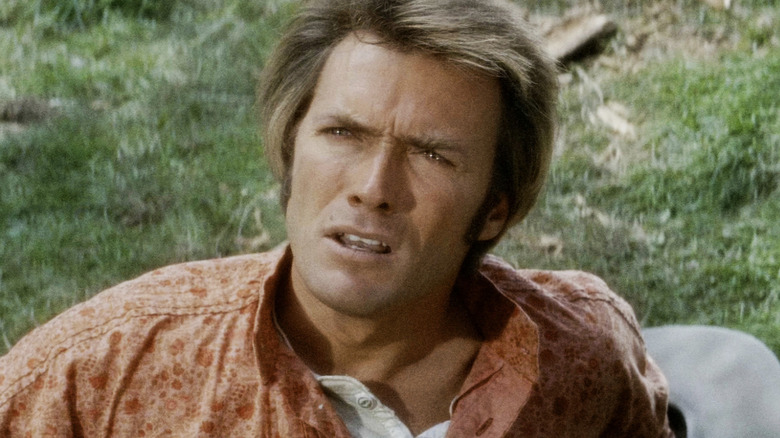

Paint Your Wagon

If John Wayne defined the Westerns of the '40s and '50s, Clint Eastwood defined the genre thereafter. The actor made his name on CBS's "Rawhide" playing Rowdy Yates, and while it took some trickery from the "Rawhide" crew to turn Eastwood into a cowboy, all it took to turn him into a movie star was Sergio Leone's "Dollars" trilogy. With those movies, Eastwood almost single-handedly ushered in the age of the Western anti-hero and the revisionist wave that became predominant in the following decades. All of which makes "Paint Your Wagon" a major outlier in his filmography.

Eastwood wasn't risk-averse. His 1982 comedy, for instance, was a major pivot for the Western actor. But in 1969 he wasn't the unimpeachable legend he would become. A big screen adaptation of Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Lowe's 1951 musical, therefore, was one of his first major gambles. With this film, Eastwood undermined his tough guy persona by playing a singing gold prospector amid the tumult of the California Gold Rush. Like his co-star Lee Marvin, he also couldn't sing, all of which resulted in what many consider to be one of Eastwood's worst films.

Directed by Joshua Logan, a veteran of the musical, "Paint Your Wagon" is more infamous than influential. But not only it was a sign of the risk-taking to come from its star, it gained a sort of cult status for being such a curious entry in the Western genre — a strange departure from the anti-heroism of its star at a time when he was at the forefront of a whole new movement that exemplified that ethos. It's arguable, then, that "Paint Your Wagon" actually contributed to the decline of the Western, but in so doing became an important signifier of where things were headed.

Once Upon a Time in the West

"Once Upon a Time in the West" premiered in Rome in 1968 but it arrived in United States theaters in 1969. With this film, director Sergio Leone solidified not only his own standing as one of the most important Western directors of the era (and beyond), he produced a paean to the genre itself and all that had come before. "Once Upon a Time in the West" was a twist on the genre's greatest hits, referencing countless beloved horse operas from "The Searchers" to "Fort Apache" and everything in between.

The film is a revenge story starring Charles Bronson as the enigmatic Harmonica, a gunslinger who arrives in the town of Flagstone but whose aims remain mysterious until the final shootout. Meanwhile, rail baron Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti) is intent upon securing the land around Flagstone for his railroad project and dispatches the ruthless Frank (Henry Fonda) to secure it from owner McBain (Frank Wolff). Jason Robards' Cheyenne is a bandit who suddenly finds himself blamed for McBain's death.

Like with Leone's "Dollars" trilogy there are no good guys and bad guys here (though Frank is about as evil as they come). Instead, "Once Upon a Time in the West" further solidified the revisionist Western as the de facto form of a genre that was on its way to falling out of favor. The 1970s would see the Western die a death, but with "Once Upon a Time in the West" Leone pulled off a coup that saw him marry the tropes of more traditional oaters with a decidedly modern (for the time) Western ethos. It was a love letter to the Western and a masterful deconstruction of that same genre.