Ella McCay Review: James L. Brooks' Screwball Melodrama Revels In Being Old-Fashioned

Remember the old adage, "they don't make 'em like they used to"? In most cases, it's a phrase used by older folks to lament the changing of the times, and to mark how much they miss cultural elements which have been left behind. It can frequently be misguided, as it dismisses progress out of hand and looks back at the past through rose-colored glasses. Every once in a while, however, it's used correctly as a way of lamenting things that we've lost which perhaps we should've held onto a bit more tightly. At its best, the sentiment is the very definition of bittersweet.

That bittersweetness is lingering throughout "Ella McCay," the new film from writer/director James L. Brooks. It's his first movie in 15 years, though that's not for any lack of work on Brooks' part, as he's been involved as a producer on films like "The Edge of Seventeen" and a little series you may have heard of entitled "The Simpsons" during the interim. Yet it still feels like Brooks' return to directing should be highlighted, especially as he's made some stone-cold classics ("Broadcast News" and "As Good as It Gets") as well as some more uneven films like 2004's "Spanglish." So far, the reputation of "Ella McCay" is leaning toward the latter category, especially as it's become Film Twitter's meme-friendly punching bag during the busy holiday release season. Yet the movie's commitment to old-fashioned screwball melodrama in an irony-poisoned world feels commendable, if not brave, and it makes "Ella McCay" more than just an easily dismissed treacle. "Ella McCay" the movie and the character are an odd fit, which is something Brooks seems to understand and revel in, and it's why I'm mostly on its wavelength.

James L. Brooks and his cast take a knowingly arch approach to characters and dialogue

Brooks establishes the fairy tale-esque approach to "Ella McCay" right away, as the whole film is being narrated by Ella's friend and secretary, Estelle (Julie Kavner), who's only too happy to break the fourth wall. In addition to telling us the general life story of our titular heroine, her family drama, and her relationship troubles, Estelle focuses on a period of Ella's life in 2008. During this year, Ella's mentor, Governor Bill (Albert Brooks), gets promoted into the Obama administration, leaving him to grant her the job of governor. Ella is portrayed with a mixture of screwball pluck and heart by Emma Mackey, and the character's aspirational idealism feels more honest coming from a late twenty-something actress playing a woman in her mid-30s. Sure, that's not a huge gap, but it underlines the way that Brooks approaches Ella in a similar manner as Lisa Simpson: a girl who has the smarts and gumption to actually make a difference, if only the patriarchal world would let her.

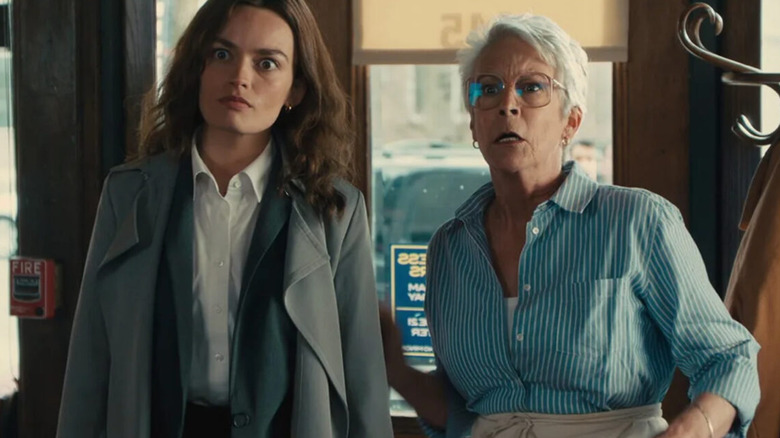

As that description implies, "Ella McCay" exists in its own fantasy version of the real world, and thus any semblance of realism in the film itself is incidental. While this could be written off as Brooks losing his touch or falling into an antiquated mode of screenwriting — the man has been working in film and television professionally since the 1960s, for goodness sake — it's so uniform that it feels like a deliberate choice. Every actor, from Jamie Lee Curtis as brassy aunt Helen to Spike Fearn as Ella's brother and Ayo Edebiri as Spike's ex-girlfriend, is given such stylized patter dialogue to speak that they can't help but undo decades of Method-style acting. It takes some getting used to, but I ended up finding it delightfully, hilariously arch.

Ella McCay resembles the more earnest films of the past

It's easy to see a lot of "feel good Oscar bait movie" material in "Ella McCay," and at a glance, one might assume that it's this subgenre which Brooks is throwing back to. In addition to the characters and performances being so arch, there are soap opera shenanigans aplenty, most of which revolve around Ella's troubled relationship with high school sweetheart Ryan (Jack Lowden), as well as her issues with her philandering father Eddie (Woody Harrelson). It's not like Brooks hasn't earned those comparisons; after all, his second feature was 1983's weepie "Terms of Endearment." Yet just as that film is more than its surface-level dramedy, "Ella McCay" isn't merely Brooks on autopilot. The movie may sound like a Lifetime original on paper, yet Brooks has tapped none other than Robert Elswit as his cinematographer. Elswit gives the film a look of winter warmth which befits a number of East Coast cities. It's ideal for Brooks' fairy tale aims with the story, as the script specifically does not mention which state Ella is becoming the governor of.

Despite Brooks' filmography, "Ella McCay" feels closest in tone to the earnestness of Frank Capra. Given the political themes, "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington" and "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town" are the most apt comparisons, as "Ella" feels as genuine in its affection for its idealistic title character as those films do. There's also a lightly sardonic thread in the film's portrayal of small town life, one which makes it feel akin to something like Robert Benton's "Nobody's Fool," another wintry movie about a misfit maverick who speaks their mind. Again, these types of films are largely out of fashion today, but Brooks either doesn't know that, or doesn't care.

The most interesting quality to Ella McCay is its subtext

Sure, there's a good possibility that all the oddities I see as a plus in "Ella McCay" are incidental. Perhaps Brooks is simply making a movie the only way he knows how. Or maybe he's staunchly making his kind of movie, something similar to the way they used to make 'em. Yet Brooks' fairy-tale trappings and the film's fable of a woman trying to have it all (and who shouldn't be denied any of it, save for the sad bureaucracies and glass ceilings of our world) seems to paint a more pointed picture than that. Maybe Brooks is lamenting the loss of the more earnest, more openly stylized type of filmmaking that "Ella McCay" appears to rejoice in, but it seems more likely that he's lamenting a period when so many of us last had hope in our country.

Of course, Brooks would never be the type to come for America's throat a la Scorsese, nor is he a subversive historian like Zemeckis. Yet there is a bittersweetness to be seen in "Ella McCay," as the movie openly wonders whether hope in our political system is as outdated as everything else. This theme may be fully intentional or it may be coincidental, yet it feels heartfelt in either case. Sure, the characters in the film don't talk or act much like real people, but for the most part, they act in a heightened manner that I sometimes wish we could. Perhaps some might think this approach has little value today, but "Ella McCay" is earnest enough to make an impassioned argument for it. There's no question that the past is gone, but maybe not everything it stood for should go with it.

/Film Rating: 7 out of 10

"Ella McCay" is in theaters everywhere December 12, 2025.